Seigen Ono is a recording engineer and artist. Fresh in our minds are the re-release of his album commemorating the 30th anniversary of COMME des GARÇONS SEIGEN ONO, and the coinciding release of his new work, CDG Fragmentation, which includes compositions of live sounds from a fashion runway. The hubbub of the audience, the clicks of camera shutters… In the hands of Seigen Ono, these fragments of sound that burst out of nowhere become music, just like special ingredients bringing texture and taste to a dish. For Seigen Ono, who has a keen insight into sound and the environment that surrounds it, what does ongaku mean? Music critic Shinya Matsuyama has a vast experience in reviewing compositions and writing liner notes. He has been a long-time observer of Seigen. In this interview, he will try to discover the relationship between sound (oto) and music (ongaku).

『20200609_HARAJUKU 1』

© Seigen Ono

Encountering Noise, Harmonizing Sound

Shinya Matsuyama:Seigen, do you consciously listen to sound and music in your daily life when you’re not creating artworks?

Seigen Ono:I don’t think it’s conscious. Since my job is to record sound and music, I’m sure I’m rather unaware of it in my daily life. But if I hear music that I don’t like, I’ll react against it as strongly as if it were cigarette smoke. [Laughs] If I’m in a shop, I’ll leave. And also, unconsciously, there are things I notice. A recent example is at a café I was going to every morning. They had a machine there for kneading dough, and the rhythm of the sound it made was samba. I thought about sampling it and turning it into a piece of music.

Matsuyama:So you get your music from the sounds of nature and daily life, not just the sounds of instruments.

Ono:I actually recorded the sound of that kneading machine on my iPhone! If you listen to just the sound, I tell you, it is a perfect samba beat. I even went to the trouble of recording it on a portable recorder. One day, though, the café started playing background music. From that point on, only mere clanking could be heard, and so I stopped going there.

Matsuyama:Seigen, remind me, when did you start using so-called non-instrumental or non-musical sounds in your works?

Ono:It was in fact for my first album, SEIGEN (1984), that I began incorporating sounds, or noise, into my music. It included the sounds of New York City streets and parks. In my second album, The Green Chinese Table (1988) , I used background noise from everywhere. In “The Pink Room” track, I used the buzz of an audience in a concert hall before the curtain opens, and reversed it. There’s a unique tension before a performance and during intervals. The buzz of a street corner, the hubbub in a hall. The live sound on the runway, the size of the venue and the number of people in the room before the show… if I were to put it all into words, they would be described as a “hum” or “buzz,” but the scene—the size of the auditorium, the number of people, the pre-opening atmosphere—is totally different, right?

Matsuyama:So you’ve been aware of noise from the beginning as a musician?

Ono:I hadn’t really thought about it until you asked me this, but the movies I was watching in high school had a big influence on me. I didn’t go to university, and instead, worked as an assistant at the long-standing Onkio Haus studios for two years from 1978 to 1980. I gained on-the-job experience with commercial film editors, projectionists, and professional recording of the sound that is added to the film. For instance, on film sets, I would hold the boom microphone for actors. Thinking back now, it was an invaluable experience. Even after switching to music recording, visual collage naturally became my style.

Matsuyama:Do you reckon you see noise, in and of itself, as a kind of musical sound, as one element of an ensemble?

Ono:Yes, I’ve come to treat noise as a musical element, just like the sounds of an instrument being played or a sampler or tape editor. Suppose a script says, “A woman wearing heels walks in a bar.” To represent the bar, you can hear the distant clink of glasses. And what of the floor? Is it marble? Wood flooring? A sole of harder material will sound more like a pair of high heels. And what about the tempo of the woman’s walk? There is even a profession called “Foley artist” to create sound effects that sound more conceptual than they actually are. Rather than perceiving noise as an instrument, if you work in recording, you realize the importance of noise. People often aim for a particular sound and try to get a clean recording, right? They either move the microphone closer, or to prevent interference from ambient sounds, they use a super cardioid (super unidirectional) microphone or shotgun microphone which records sound only in the direction it is pointed. Like a zoom lens, it picks out only the object you were closing in on. But elements that end up being shed, that is, everything other than the object—so-called ambience and background noise—are surprisingly important, right?

Take for instance this plate of curry on the patio here which is bathed in sunlight. The curry looks absolutely delicious, but trying to reproduce the same light situation in the studio is very difficult. A spotlight mimics the direct sunlight, and the reflected light creates shadows. In terms of sound, the reflected sound creates shade around the curry and dominates the space. Even though it seems like the objects are captured by spotlights and super cardioids, the important noises and reflections that used to enhance the sound are now missing.

Matsuyama:You’re saying that music comprises feedback and harmony of all sounds in the world, so some music inevitably contains noise.

Ono:That’s right. One of my albums, Forest and Beach (2003) , has five-channel surround content, but it’s impossible to extract the sound of waves from the beach. What is the sound of the waves? What is the sound of the wind? The rumbling sound of waves hitting, moving and rubbing against pebbles and sand is accompanied by a very high frequency of microbubbles with a fizz. The same goes for wind in the trees rustling leaves against each other. If you think about it, waves and wind have no sound; we sense the various noises, which are made by the energy of the wind and waves, as the sound of the wind. So, suppose for example that delicate, quiet music is playing. A roaring wind blows. The sound of the wind, or the sound of the waves, stops suddenly, and in that moment of silence, even though you haven’t turned up the volume, the music stands out as if suddenly under a spotlight. When recording music, the expression “noise” is spoken as if it were garbage, but musically speaking, it can also be viewed as a decoding that is out of tune and clashes.

Painting the landscape with sound

Matsuyama:Speaking of noise, the first 40 minutes of CDG Fragmentation, which was released last year with the reissue of COMME des GARÇONS SEIGEN ONO, contains the live sound of the runway at a Comme des Garçons show.

Ono:Chapters 1 to 6 of the CDG Fragmentation are real sounds recorded in real time at the 1997 Paris Fashion Week. There are photographers calling out to the models, the clicking of their cameras, hands clapping, the sounds of shoes, and the hum of voices. At the show, for each model, I played a set of various sounds that I had put into the sampler. For the first five minutes or so, the audience seemed to think it was an acoustic mishap. But as I adjust the sound like an anime to match the model’s gait, the audience gradually catches on that it is part of the production. It’s even more realistic to the people who were there. I was in two minds right up to the last minute about whether it was OK for the first 40 minutes on a new album being released by a major label, namely Nippon Columbia, to consist only of live sounds (about 100 minutes long in total). But on hearing this, photographer Kazumi Kurigami said to me, “I want to use this in my studio.” I guess he doesn’t play so-called background music when he’s doing photo shoots in his studio. More than music, he was interested in being able to reproduce the feelings of tension that build up at a show. That clinched it for me. The fact you can record and reproduce in sound about 40 minutes of tension and atmosphere was also a discovery. What did you think, Shinya?

Matsuyama:In a sense, I thought it was more eloquent and realistic than the music in that it made you imagine the clothes, the environment and culture surrounding the clothes, and even the faces and passion of the designers.

Ono:Apparently, Comme des Garçons didn’t use any music at all during a number of shows prior to 1997. Then in the commission I received from Rei Kawakubo, she said that she wanted to use “sound” but not “music.” Although it was like a Zen riddle, I defined the difference between music and sound for that presentation. Since it was Comme des Garçons, the idea of sampling any old fragments from records wouldn’t do. So, I went to the trouble of recording fragments of sound. But you can’t just order musicians to play fragments at random. I wrote a score to give to the musicians, and I recorded myself at the piano to act as a guide. These, however, only included chords and a simple melody. I call this “Lurking Tonality Piano.” Ha! I wonder, can it be called an invention? Anyway, based on the piano as a guide, and with the instruction to not participate as an ensemble, I proceeded to record the musicians, one or two at a time. The musicians, however, could not hear each other. During the mix, I muted my piano. The fortuitous result contrived from this process were a couple of pieces that clearly show some tonality but without ensemble: the 9th track on the album “Jean from 3rd street” and the 11th track “John from 3rd street.” Another possible way of looking at this is wondering how actors will act after reading a film script, or in this case, the musical score. At the show, we only used fragments from these pieces. Based on this “Lurking Tonality Piano,” I also recorded a new piece—the 10th track “At long last”. I find this approach interesting, and is one that I’ve adopted again—on a synthesizer this time—for the new album that I’m producing during the current #StayHome period.

Matsuyama:You were heavily influenced by films, or rather, it’s the foundation of your work, isn’t it?

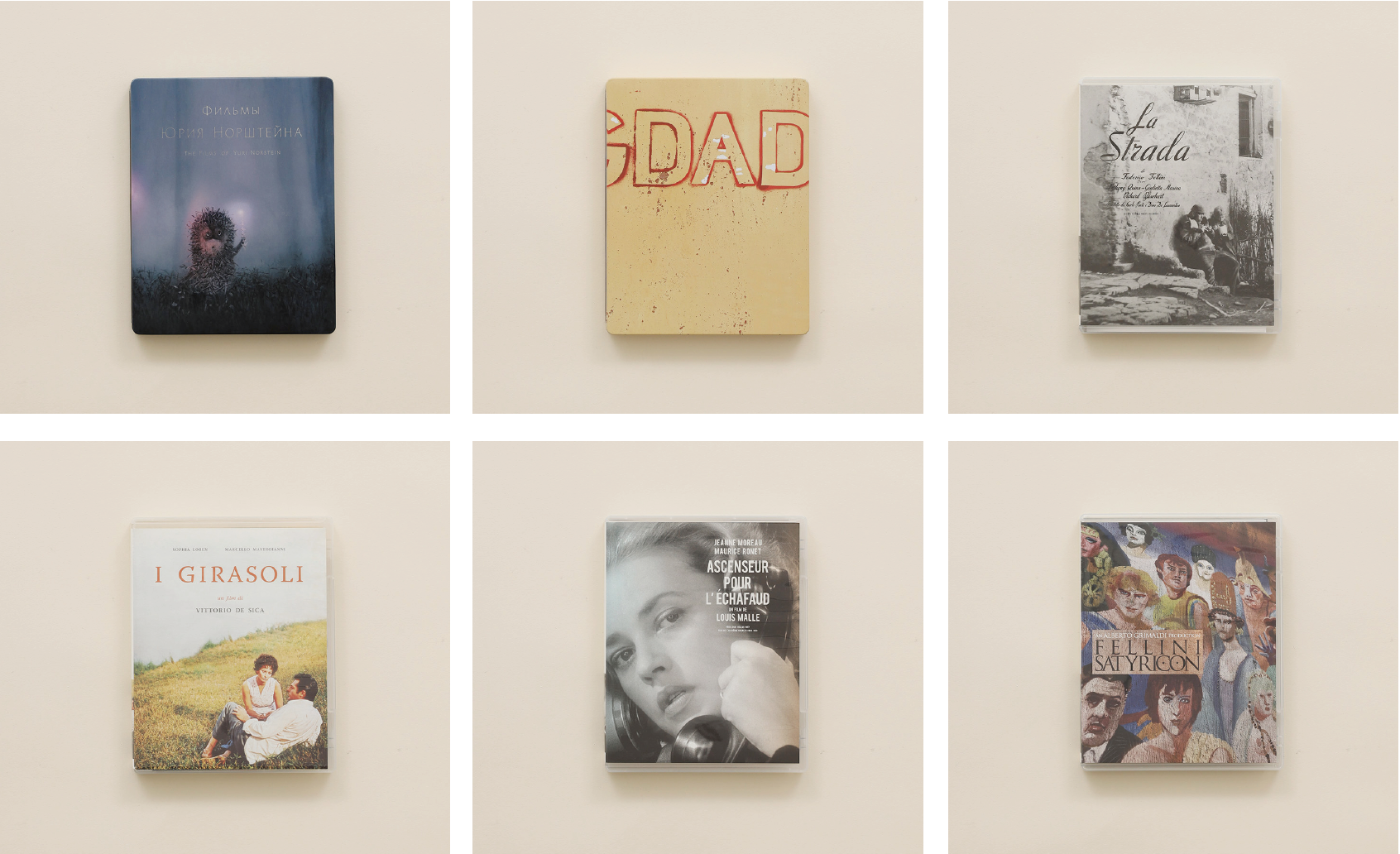

Ono:I recorded the album Bar del Mattatoio (1994) between 1988 and 1994 in places all over the world: Sao Paulo, Rio, Paris, Milan, Tokyo, New York… In retrospect, I’m still glad I made that album. Caetano Veloso, who I love, wrote the liner notes for the album, which made it a complete work of art. The answer to your question also lies there. While I don’t compose soundtracks, I was heavily influenced by films. Films by Fellini with Nino Rota’s music, Yasujiro Ozu and others. The genre of montage recording was created with their works in mind.

It’s also interesting to see that space-time is different between video and sound, like in films by Jean-Luc Godard. In films, there are things that aren’t shown on the screen, and there are things that are connected by sound and music to move on to the next scene. It’s like in the 1984 video work released by JVC, MANHATTAN—which has close ties to my first album, SEIGEN. When asking Masanori Sasaji to compose a piece for the opening scene, we had meetings about instrumentation and chord. My brief for the sample really went something like… the intro will be like the interval music from Death in Venice (1971) directed by Luchino Visconti (the fourth movement “Adagietto” from Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 5), and the rest will be like Bill Evans. Once I’d specified the worldview, or broad framework, the rest was up to the composers and musicians. Within that framework, they were given free rein.

Matsuyama:Wow, I didn’t know I had pointed such a specific example!

Ono:Even though it’s music, the sound created by Takemitsu feels like it is painting a scene, doesn’t it?

Matsuyama:In his case, it’s like he’s using sound to create images. He’s a composer and a film director by trade. He doesn’t just use music written in the score, but also electronically modulates the recorded sounds to make noise, and then makes them sound like he’s making a film. And so on. He also uses a lot of environmental sounds, and in his mind, the noise is also music and images.

Ono:Memorable among recent film scores is the score composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto for The Revenant (2016). The tremendous visual images of nature and the cold are certainly stunning, but also there’s no boundary between natural sounds and music in the soundtrack, is there? It seems they’ve also used the “Glacier” music from his Out Of Noise (2009) album. In describing the sound of Arctic glaciers and water in the liner notes, he writes, “I left various sounds based on the sound of pure water several thousand years old.” If watching the movie on a DVD or TV broadcast, these sounds get compressed using AAC and so you can’t hear the detail. While The Revenant is therefore best listened to in a good cinema, it also sounds really good on Blu-ray with a good system. There is no division between the quiet, delicate sounds of nature and the sound of the synthesizer that whooshes in behind. It was brilliant, wasn’t it?

Matsuyama:That’s true. Sakamoto is very good at blending delicate electronics with noise-like sounds from nature. He’s been consistent since the 1970s. I sense he’s been constantly thinking about the division, and the shared domain, between noise and sound.

『20200609_HARAJUKU 2』

©Seigen Ono

Observation of music beyond the conscious and subconscious

Ono:That said, what do you imagine if you see “sound of wind,” for instance, written in the stage directions of a script?

Matsuyama:The sound of wind… the sound of a glass window rattling, or…

Ono:Wind, you know, doesn’t really have a sound. Actual wind. Then there’s the phrase “sound of rain.” But rain doesn’t have a sound either. Same goes for “sound of waves.” At the water’s edge, or where waves break and strike the rocks, there’s the sound of sand being shuffled by the wave, right? It’s the same with wind as it hits leaves. The rustling sound we hear is that of leaves rubbing against each other. And then there’s unwanted noise, right? Since we’re doing this interview outdoors, later when you transcribe the tape, it’ll be hard to follow because of the buffeting. This buffeting is the sound of wind hitting the grille on the IC recorder’s microphone. It’s the same as the whistling noise you hear when you open your car window while driving. It’s a noise that is not needed for this interview. But the whistling noise would be OK though if the stage directions said, “Sound of wind.” Recording the sound of leaves rustling might be quite difficult.

Matsuyama:You’ve got me worried now, so… [wraps a paper napkin from the café around the IC recorder microphone] I know how hellish it can be if you can’t transcribe from a tape because of noise.

Ono:Just now, a plane flew overhead on the new flight path to Haneda, but we were able to continue this conversation, right? The sound of the airplane recorded on your IC recorder should be much, much louder than our voices. But we humans are able to capture sound three-dimensionally, and if our consciousness is directed here (to this conversation), in our minds, we can cancel (ignore) the surrounding sounds (noises). Machines, though, are unable to do this, so when you try to transcribe it later, only noise will be recorded, and you won’t be able to hear this critical interview! It’s called the “cocktail party effect”—the ability to focus only on what you want to hear from among multiple conversations going on at the same time at a party. Human ears are amazing, aren’t they? The ability to differentiate sounds is one we all use unconsciously.

Matsuyama:In short, the IC recorder mechanically picks up all sounds equally without distinguishing between the sounds you want to hear and the sounds around you, but in the same way, if we humans try to listen consciously to the sounds that we’ve unconsciously removed, they may become music instead of noise.

Ono:Yes, that’s it! Like the sounds of this spoon scraping against the plate of curry we’re eating now. This is delicious! Effective sounds, you know, also influence the way we feel about things. So, I try to sample and record these sounds as reminders of that flavor.

Matsuyama :Non-musical things also become instruments.

Ono:Plates, spoons, utensils lying around the kitchen… they are in fact musical instruments. Some of my tunes that feature utensils include “Anchovy Pasta” and “Sanma Samba.” Lots of kitchen utensils produce interesting sounds. Rolling pins and chopsticks in particular know no bounds. For softly tapping a cymbal legato like a clave, chopsticks are better than drumsticks you know. And while taiko drumsticks set you back between 3 and 5 thousand yen, rolling pins are a buck a piece if you go down to Chinatown. They’ve got piles and piles of them, so you can select the ones that produce the best sound as an instrument.

Composing music like a recipe

Ono:It suddenly occurred to me yesterday, and I uploaded a piece that is going to be part of a new composition. I’ve also used three-dimensional encoding for some headphones that are under development, but hardly anyone has looked at it yet.

20200403 Seigen Ono Fragmentation 2

© Seigen Ono

Matsuyama:It’s great. It’s so vivid and heart-pounding. Seigen, you can clearly feel your sense of beauty, expression vector and emotion in this work.

Ono :Shinya, hearing you say those words makes me happy. It’s a collage of the Manaus jungle in Brazil in 2010, the sound of Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo dancers gliding across the floor of a rehearsal room in Nice in 2003, and the sound of scurrying children, combined with a variety of music tones. I feel it has a similar sensation as making pasta sauce.

Matsuyama:The vividness reminded me of works by Chris Watson, as if the smell and humidity of the wind were almost carried by the sound. One of the founding members of Cabaret Voltaire, Watson later produced a great many of his own recordings while working as a sound recordist for the BBC in the UK. Since his time with Cabaret Voltaire, he has single-mindedly pursued answers to the questions: What is music? and What is the relationship between sound and music? There have also been a number of Japanese who have incorporated field recordings into their musical works. Key figures include Amephone and Aki Onda, who lives in New York. Always found with a cheap cassette tape recorder wherever he goes, Aki Onda records the sounds of various places, and creates collages using only those lo-fi sound sources. It’s wonderfully musical, wouldn’t you agree?

Ono:When it comes to making the most of a good opportunity, scouting for a good location and positioning your microphones are more important than any expensive mic or equipment. Rather than making a reservation and going to a three-star restaurant, you’re more likely to come across the fish of the day and have a tastier meal if you drop into that place near the fishing port where the local people go to eat. With sound and video too, it’s more about content than equipment and technology, right? What image and what sound do you want to record? Questions of the composition itself and emotional performance are absolutely more important.

Matsuyama:These days, it feels like we’re too afraid of mistakes, errors and noise in all aspects, not just music. I think this is especially evident in Japan. And that’s despite superficial perfection having hardly any bearing on the depth and strength of art. More important than anything else is properly communicating what it is you want to convey, and the emotion that is contained within. Errors and noise will often clarify the essence of the art.

Ono:In commercial music, it’s commonplace now that everyone is always revising and correcting work recorded on computer. Personally, I think it’s just a waste of precious time. I don’t think anything is completely free of little mistakes. Rather than trying to fix them, I think that music that feels good and features emotion will ultimately be more appealing both for the players and their audience.

Seigen Ono

Seigen Ono launched his career with JCV in 1984 as composer and artist. In 1987, he became the first Japanese to sign a contract with Virgin Records (UK). He established Saidera Records in 1987, followed by Saidera Mastering in 1996. He has engaged in a wide variety of work, including joint development of acoustic technologies such as VR, acoustic space design, consulting, and more. He won the ADC Grand Prix in 2019.

Shinya Matsuyama

Born in 1958 in Kagoshima, Japan, Shinya Matsuyama is a music critic and author of The Age of Pierre Barouh and Saravah and BLIND JUKEBOX. He is also an editor of Perspectives on Progress and has co-authored numerous disc guides.

Interview Shinya Matsushima

Photography Erina Takahashi

Edit Moe Nishiyama