“Bikkuriman Akuma VS Tenshi Stickers,” “Wrestler Gundan Kōsō W Stickers,” and many more are collectible freebie stickers (in Japanese: シール, Japanese pronunciation: shīru) included in snacks that were incredibly popular amongst Japanese children in the late 80s. Like DNA, this particular culture has evolved and adapted to nowadays time, creating a new and booming movement of “D.I.Y. stickers.” This square-shaped, 48mm-wide world of creation, hand-made by unique artists, is just like a mandala. Leaping out of Japan and spreading around Asia like wildfire, it has now become a new communication tool connecting fans around the world. D.I.Y. stickers are not just nostalgia, but rather the latest form of expression, always in search of advanced technologies and better quality. We’re now approaching the frontlines of this new culture.

The fall of freebie stickers and the dawn of D.I.Y. stickers

1985 was a major turning point for freebie stickers, which originally were just accessories to motivate people to buy more snacks. At the time, Lotte released the “Akuma VS Tenshi Stickers,” the 10th installment of the “Bikkuriman Choco” series, accomplishing an unprecedented level of popularity. Just like a creation myth, this installment comprises an intricate and epic world design and highly unique characters, in addition to introducing the concept of rare collectibles, thus evolving into a social phenomenon for children all over Japan. As a result, in the late 80s, different brands such as Bell Foods’ “Wrestler Gundan Kōsō W Stickers,” Furuta’s “Dokidoki Gakuen Kaiun Gundan VS Yōsei Gundan Series” and more flooded the masses with their products, thus beginning the boom of freebie stickers.

However, with the heartless change of generations, new hobbies are constantly born, and old ones disappear. In the early 90s, the boom began to quiet down. After that, in 1999, Lotte released “Bikkuriman 2000,” causing another rise in popularity for freebie stickers, and at the same time, spreading a new movement centered on the people who were experiencing that boom in real-time. It is the dawn of D.I.Y. stickers.

The source of such creativity comes from an initial impulse to create and express

The term “D.I.Y. Sticker” generally comprises all self-made stickers. However, recently this term also started including stickers made to look like freebie ones.

“From the late 90s, the culture of D.I.Y. freebie-style stickers started spreading through dōjinshi conventions, but it wasn’t until the 2000s that it blossomed. I became interested in D.I.Y. stickers around 2013-2014. I am still not that experienced with them, so it might sound pretentious, but as someone who was in charge of D.I.Y. stickers at Mandarake, I would say that just like dōjinshis and zines, I think that this culture is born from the artist’s initial impulse to create and express himself.”

This is Masaki Nakatsu, in charge of Mandarake’s sticker e-commerce website “Shīru Yokochō” (in English: Stickers Alley). The site was created as a hub to simultaneously connect sticker artists and fans active all over Japan. Masaki, who is in charge of all of this, continues:

“Dōjin circle MOOK-TV has created a dōjinshi called ‘Recommendations for D.I.Y. stickers,’ which states that the first D.I.Y. stickers boom came to be around the year 2000. There were many artists at the time, but it was mostly derivative work, and only very few people made originals.”

https://www.mandarake.co.jp/content/yokocho/index_en.html

The afore-mentioned “derivative work” refers to parodies and homages of characters that appear in creative media such as anime, manga, games, and more. What about originally designed freebie-style stickers, are they considered D.I.Y. stickers? In recent years, there have been cases where some companies started producing their own originals, such as “Ramen Rally Stickers” by “Negio Corporation,” and “Yamato Shinden” by “Ihika.” Mandarake is also producing a series known as “Kyōgai Metsuden.” Outsiders of this culture might categorize them as D.I.Y. stickers, but they actually aren’t.

“All of these sticker designs are manufactured and produced by guaranteed professional designers such as Greenhouse, so I feel like they shouldn’t belong in the category of ‘D.I.Y. stickers.’ In other words, I think the most appropriate way to think of them would be as a ‘new wave’ of freebie-style stickers brought back in the present-day. It’s easier to compare them with records; D.I..Y stickers are like new indie albums.”

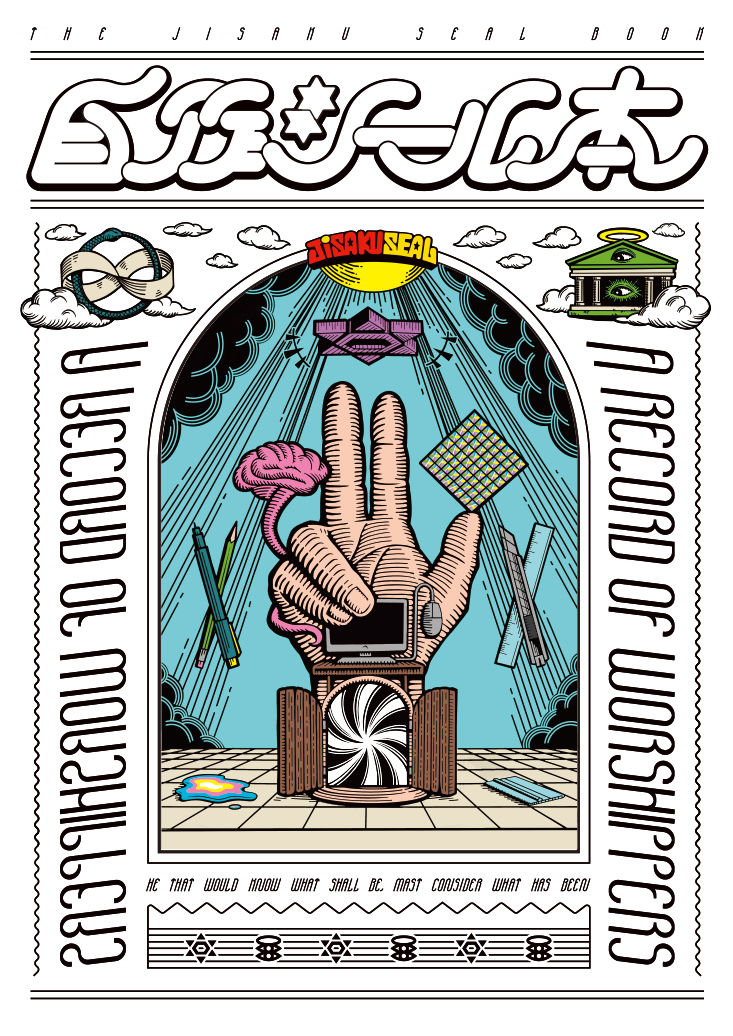

On the other hand, the indie scene always has problems regarding copyrights due to its concept of free creativity, and many stickers of mash-up and bootleg characters are likely to conflict with such issues. However, as it is possible to produce stickers as a personal hobby, it is nonsensical to think of them as plagiarism. In September, Mandarake released “The Jisaku Shīru Hon” (in English: D.I.Y. Stickers Book), a book summarizing the history of D.I.Y. stickers from the year 2000 to the present, in which many unique, although copyright-infringing works are sadly not present.

“Unfortunately, we couldn’t put any derivative works in this book, although I am drawn to their freedom and freakiness. I think that the culture of D.I.Y. stickers was able to grow so much because of the existence of derivative works and their artists, which crammed their wildest ideas and love for well-known characters into 48mm. It isn’t just me thinking this way; it’s just common sense between everyone involved in D.I.Y. stickers.

The expansion of the D.I.Y. Stickers community and its ever-evolving creativity

The people interested in D.I.Y. stickers steadily started to grow, and the community expanded. As a result, from 2006, many stickers events were being held all over Japan. Since 2016, Mandarake also has been holding an event known as “Sanchi Matsuri” once a year for the purpose of selling and exchanging D.I.Y. stickers. Due to the corona pandemic in 2020, the actual event was canceled, so it was held online instead. On the day of the event, #SanchiMatsuri could be seen on every D.I.Y. stickers’ fan timeline.

The first “Sanchi Matsuri” was held just before the second D.I.Y. stickers boom in 2014-2016, resulting in many new sticker artists joining the scene. Even now, the number of artists is slightly increasing. New artists are constantly getting better, trying to catch up to talented sticker artist Hobbit Shōten, active since 1998 and still leading the movement. By repeating this cycle, the scene stays active.

Now, we at “TOKION” have prepared a line-up of our top-pick artists to understand how the D.I.Y. sticker scene is evolving.

We start with “Happy Castle / Moza,” who has been active since 2008. The first surprising thing is their vast repertoire: from straight-up cool art of “Wingman stickers,” to art inspired by deep subcultures such as freemasonry, and “hihōkan” (in English: erotic museum), specifically made for such aficionados. Another solid example is the “Himitsu Kessha Stickers” (in English: secret society stickers), which design changes depending on the viewing angle, making the most out of lenticular materials. With his irregular round-shaped and hexagonal designs, he is definitely one of the representatives of the scene, always trying to fuse innovative ideas with the spirit of “cheap culture.”

From “Wingman Stickers” (2017-2019), “Morphoqueen” (left), “Kujaku Ō” (right)

From “Himitsu Kessha Stickers” (2019), “Computron M”

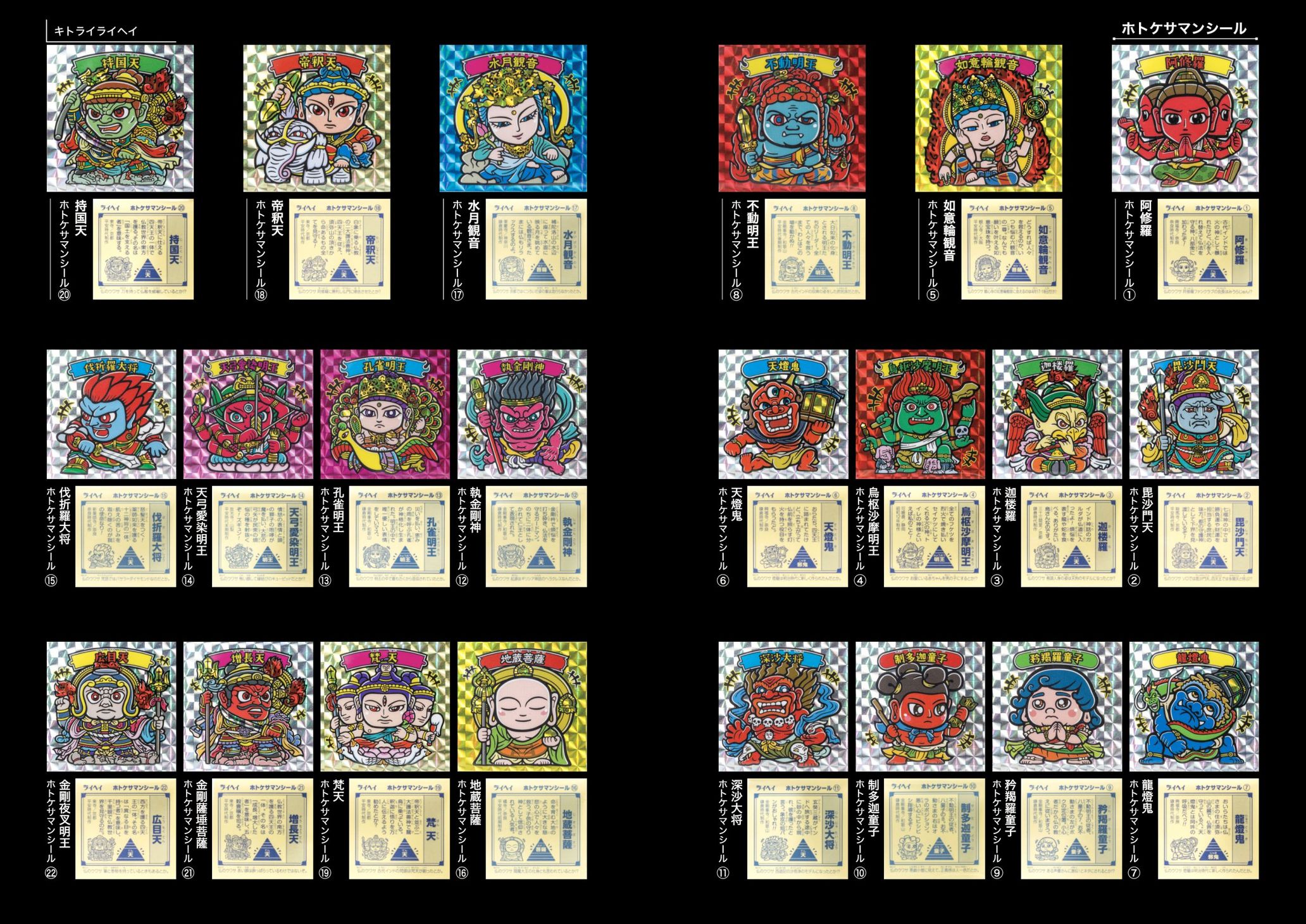

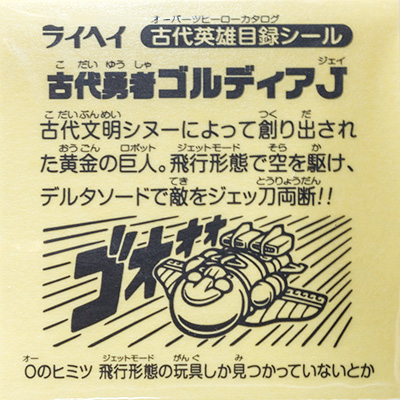

This is Kitlailaihei, who is mainly a graphic designer. He started drawing stickers around 2007 at a rock bar he frequently goes to, drawing heavy metal musicians in the style of Bikkuriman characters and showing them to friends. He started drawing stickers professionally around 2013. He is popular not only around D.I.Y. sticker fans but also among heavy metal fans. His designs are combinations of innovative motifs, such as O-PartsXHeroes and curry, to his deformed and cute style. His uniqueness is blatantly exhibited also through his buddha-styled “Hotokeman Stickers.”

From “Hotokeman Stickers” (2019), “Amitabha triad”

From “Kodai Eiyū Mokuroku Stickers” (2018), “Kodai Yūsha Goldia J”

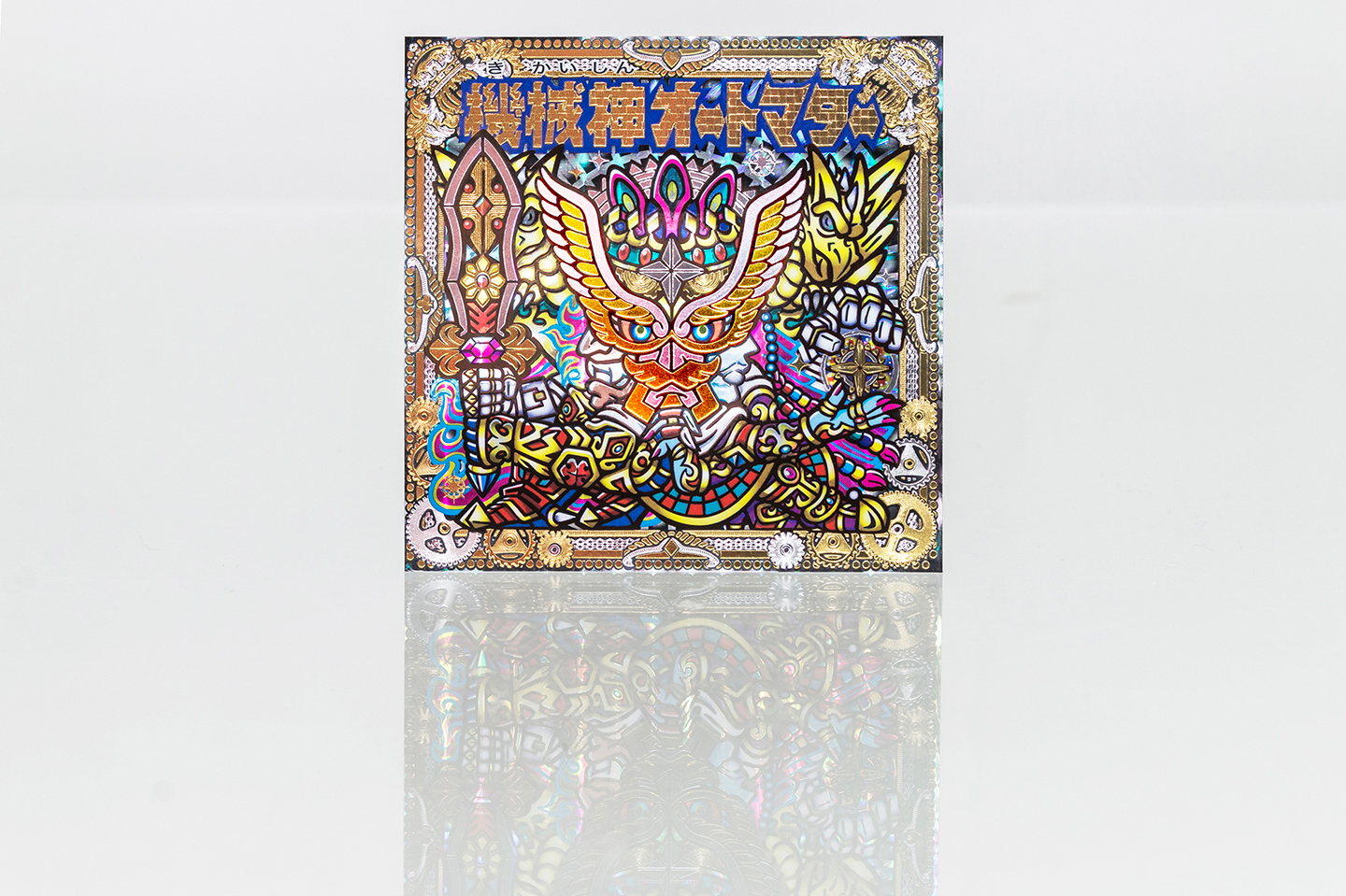

This is OHT Stickers / Ohtoman, active since 2014. His series “Legend of King Arthur,” which perfectly embodies the eccentrically subtle designs and complicated printing techniques, was very well accepted by D.I.Y. sticker fans. Instead of doing it himself, he entrusts the printing process to professional companies, thus achieving an incredibly high level of production, using various techniques such as gilding gold and silver into prisms, and lamé printing, to exploit the 48mm’s limitations to the fullest. This series is currently incomplete. We’re looking forward to seeing how his methods of expression and techniques will evolve in the future.

From “Legend of King Arthur” (2017-), “Kikaishin Automata” (96mm)

From “Legend of King Arthur” (2017-), “Shin-Ō Arthur” (left), “Shugosha Black Knight” (right)

There are still many other artists with unique abilities and ideas, such as: “Zenmetsu Bunka Kyouzai Sha / Doku,” who formed a unit with model sculptor “Pirawo” and have been releasing their products with 3D models; “Dr. Dokuron No Yabō / Bakurikko,” who also writes his own manga while producing stickers; “Chōnōryoku Boys / Yuri Gerō,” with his characters designs based on dice.

Transoceanic communication through 48mm

Although the D.I.Y. sticker culture is constantly growing to this day, it is still hard to say whether it will spread all over the world. At the same time, D.I.Y. stickers are becoming extremely viral in Hong Kong as much as in Japan. In 2019, despite the unstable circumstances, the first D.I.Y. sticker event was held in Hong Kong, also known as the “First Hong Kong Sticker Fair 2019,” which lots of fans of the D.I.Y. sticker culture attended. We asked Nakatsu-San about it, who traveled to Hong Kong and felt first-hand everyone’s enthusiasm at the fair.

“I heard that they used to sell snacks with freebie stickers in Hong Kong too, same as in Japan. So, similarly to Japanese fans, the people of Hong Kong are also familiar with this culture from an early age. In that sense as well, it can be said that this culture was naturally accepted because of their mentality towards D.I.Y. stickers and “cheap culture,” being close to ours. In reality, the D.I.Y. sticker culture in Hong Kong was not passed from Japan, but it originated from there, from their will to make something specifically like that, and we also got to understand their appeal.”

These are pictures from the “First Hong Kong Sticker Fair 2019” held in Hong Kong. Nakatsu-San came all the way from Japan and also participated in the event.

From “Bantenkaiki,” “Banko-Shi”

From “Hong Kong Shinwa ‘Shinkaihen,’” ”Kyoganjutensen” (stickers and action figures)

These two artworks are made by artists from Hong Kong. It is very interesting how the stickers are “localized”: some of them are inspired by Chinese myths, while others utilize designs and tones characteristic of Hong Kong while resembling Japanese ones. To conclude, we asked Nakatsu-San about the future of D.I.Y. stickers.

“Even among people who have never been interested in freebie-style stickers, such as celebrities and artists, a fun trend of creating business card stickers that look like freebie-style stickers, is growing. So, I hope that some of those people will dig deeper and find out about the D.I.Y. sticker culture. I am looking forward to when this culture will spread from Asia to Europe and America, and all over the world.”

Long ago, Buddhism, which was once brought to China from India through the Silk Road, has spread across the sea to Japan. In esoteric Buddhism, the mandala was drawn to express Buddha’s words of enlightenment and the concept of creation through abstract and symbolic pictures and letters. I feel like the way D.I.Y. stickers express different elements is very similar to that. This concept, once again, crosses the sea from Japan to the world. This new and limitless form of expression and communication tool is expanding all over the globe.

works cited “Jisaku Shīru Hon”

published by Shīru Yokochō Operations Department

sold by Mandarake Publishing Department

pictures provided Shīru Yokochō Operations Department

Translation Leandro Di Rosa