Poet Tahi Saihate’s solo exhibition, We are the 6th magnitude star of the night, born to keep this distance, opened on December 4th at Shibuya Parco and is ongoing until the 20th of this month. It will then be held at Nagoya Parco from February 13th to 28th of 2021 and Shinsaibashi Parco from March 5th to 21st of 2021. Saihate’s aim is for the visitors to complete the poems by being there. We asked her what her true intentions are behind this exhibition.

——Could you first talk about your current exhibition?

Tahi Saihate (Tahi): I had my exhibition, Water below 0°C about to become ice, Or a chrysalis about to become a butterfly, Or a museum about to become poetry, Tahi Saihate: Exhibiting Poetry, last year in February at the Yokohama Museum of Art. Afterward, they asked me to take it nationwide, and the plan was to go to Kyoto, Fukuoka, and back to Tokyo. But the one in Kyoto got canceled because of coronavirus. Nevertheless, the exhibition ran from August to September in Fukuoka, and the most current one is in Tokyo. I’m planning on doing it in Nagoya and Osaka next year. Honestly, I didn’t think it was going to get this big.

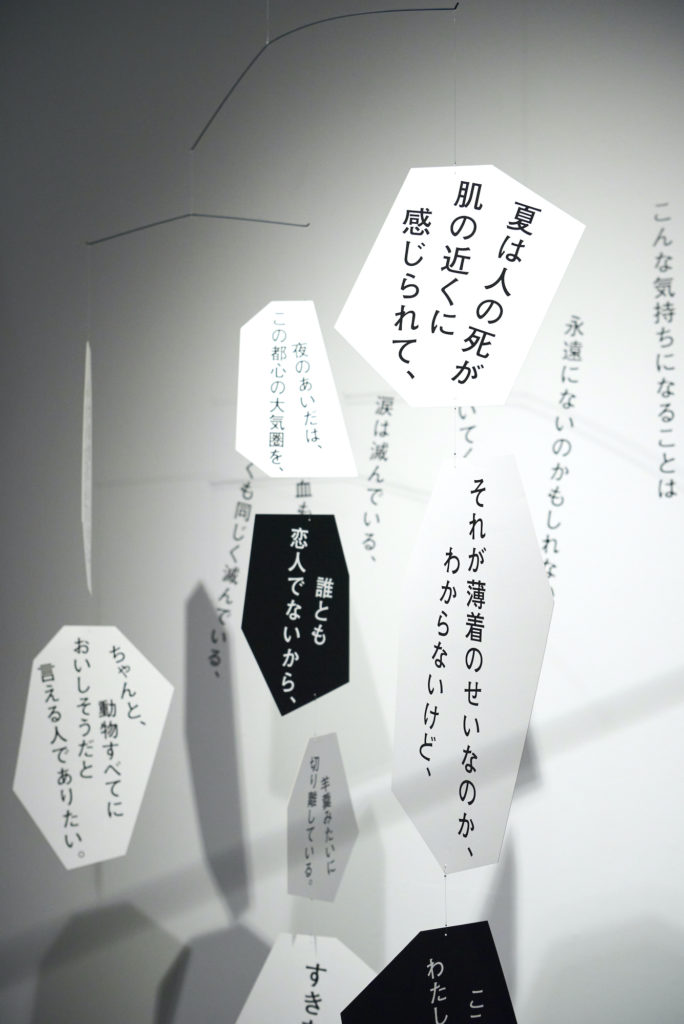

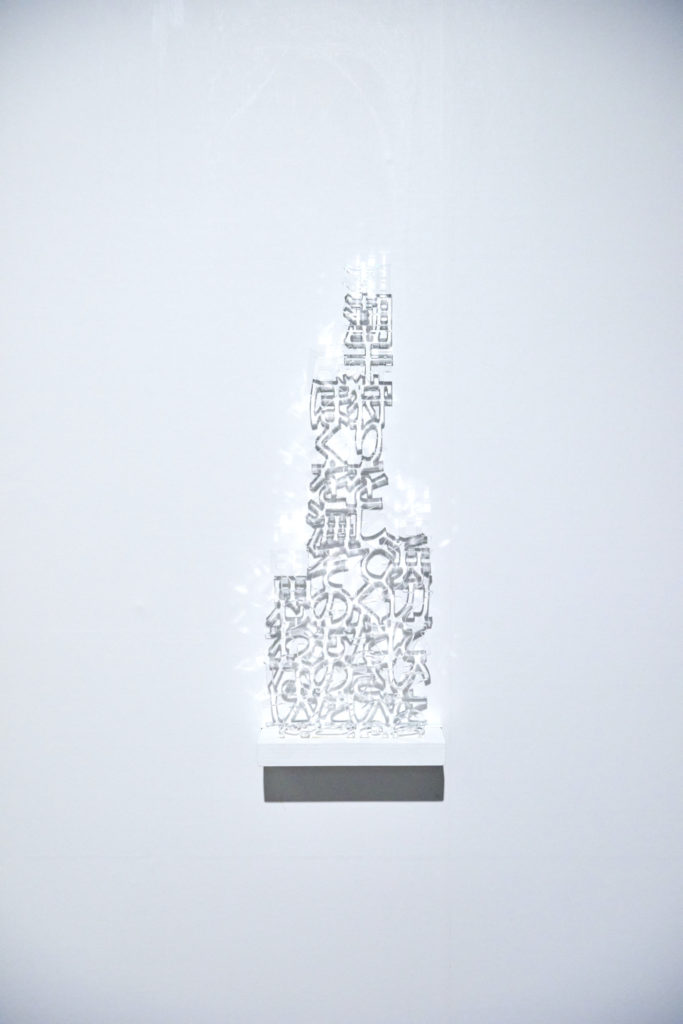

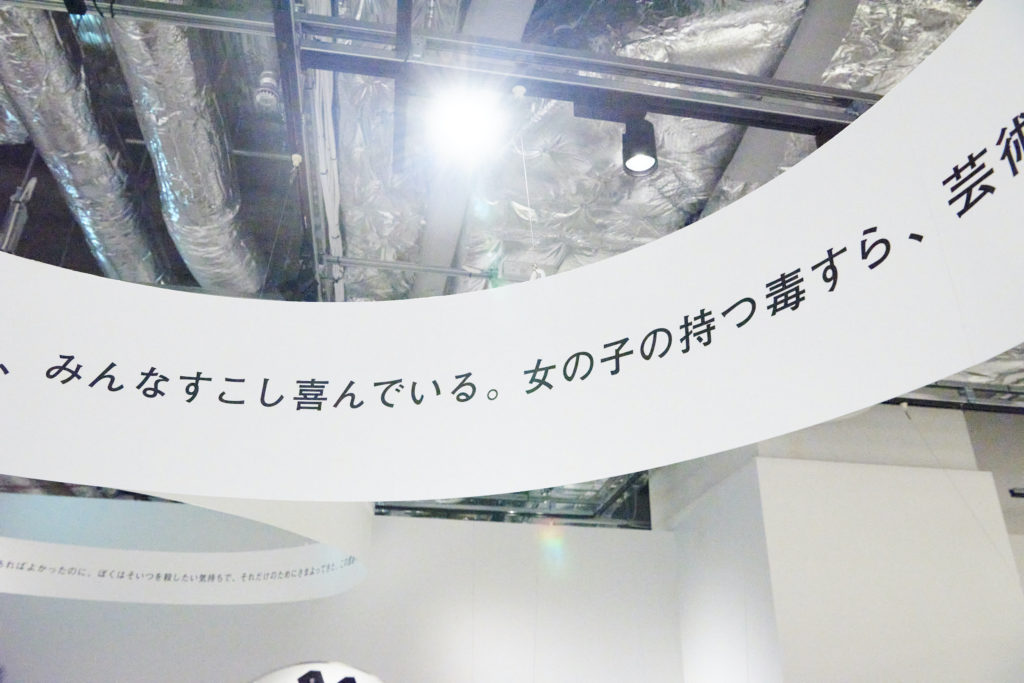

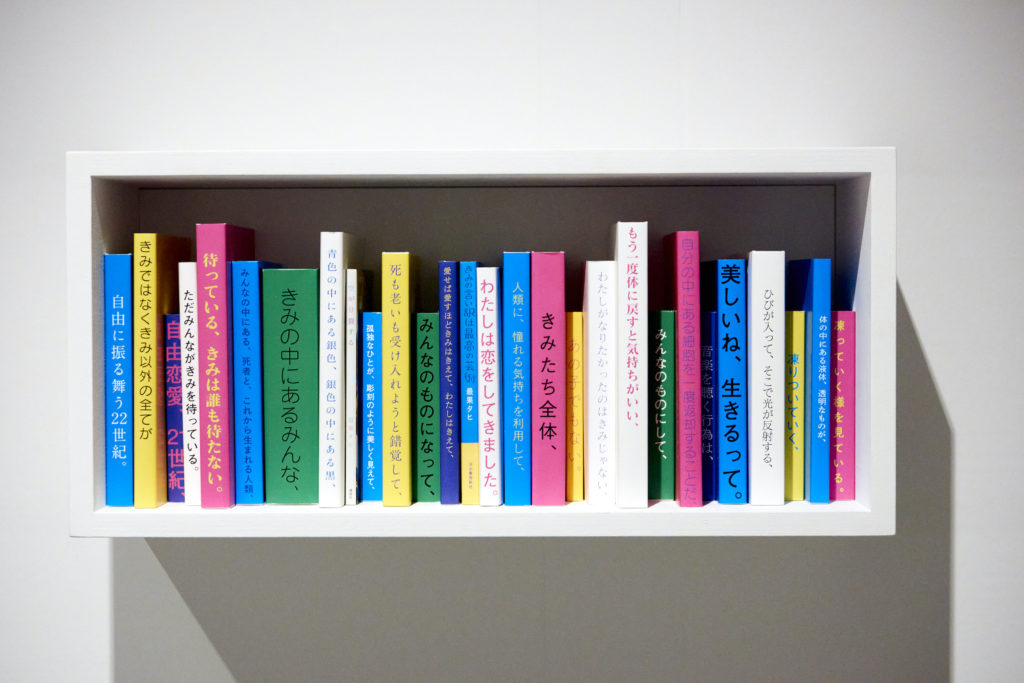

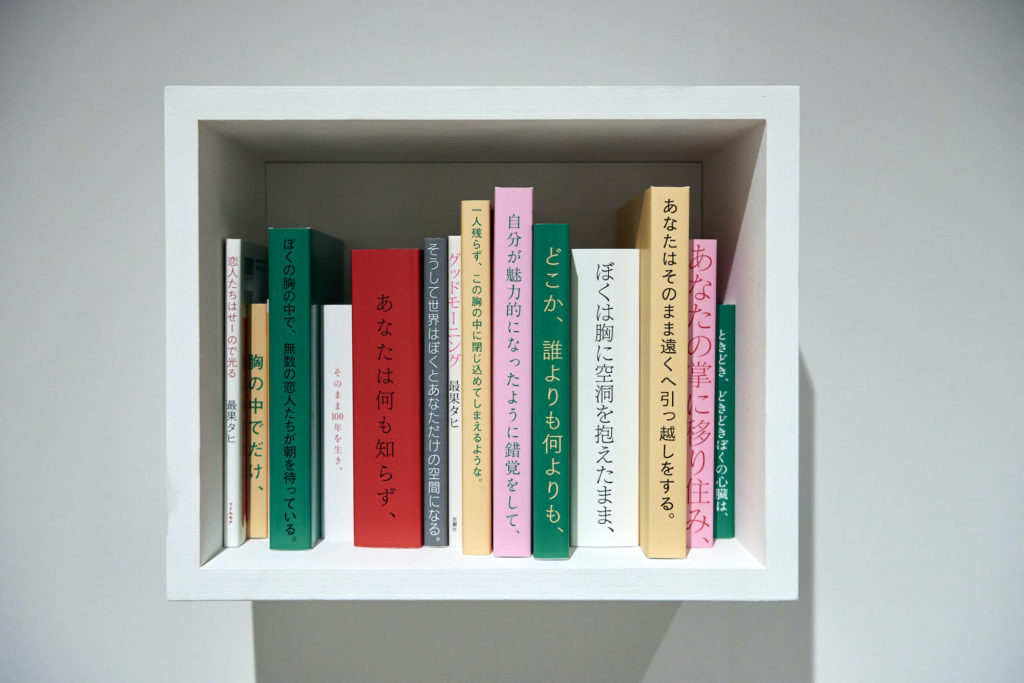

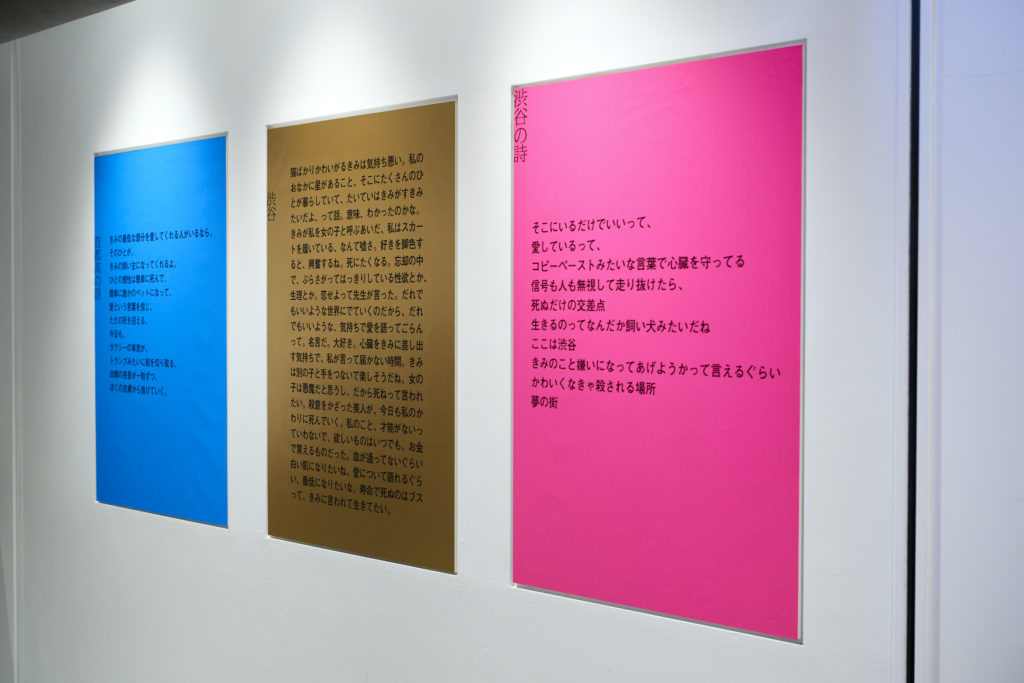

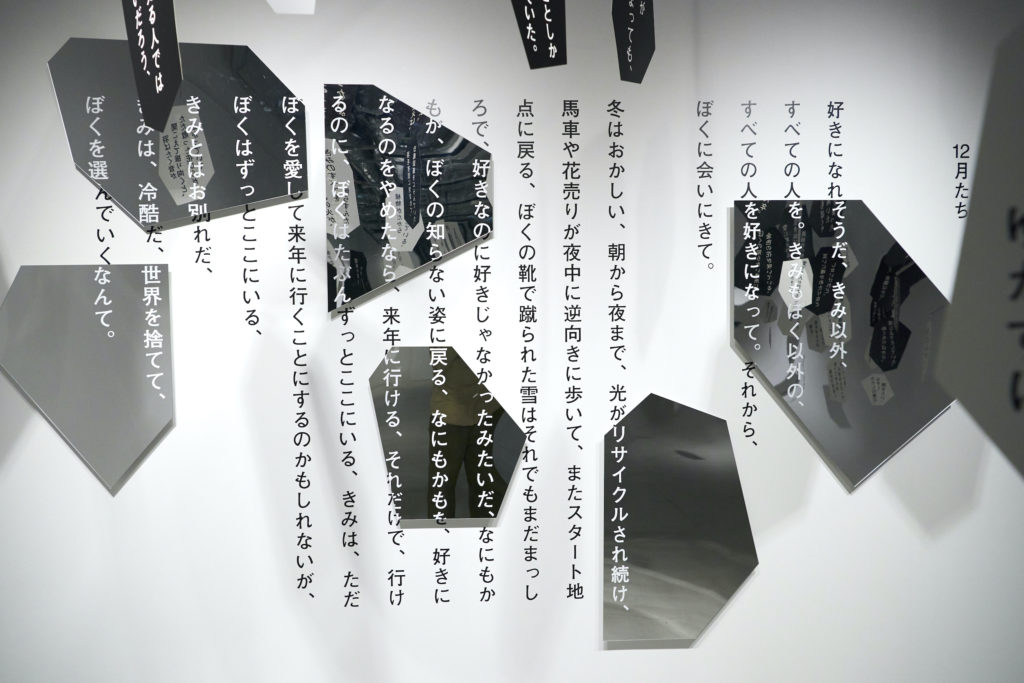

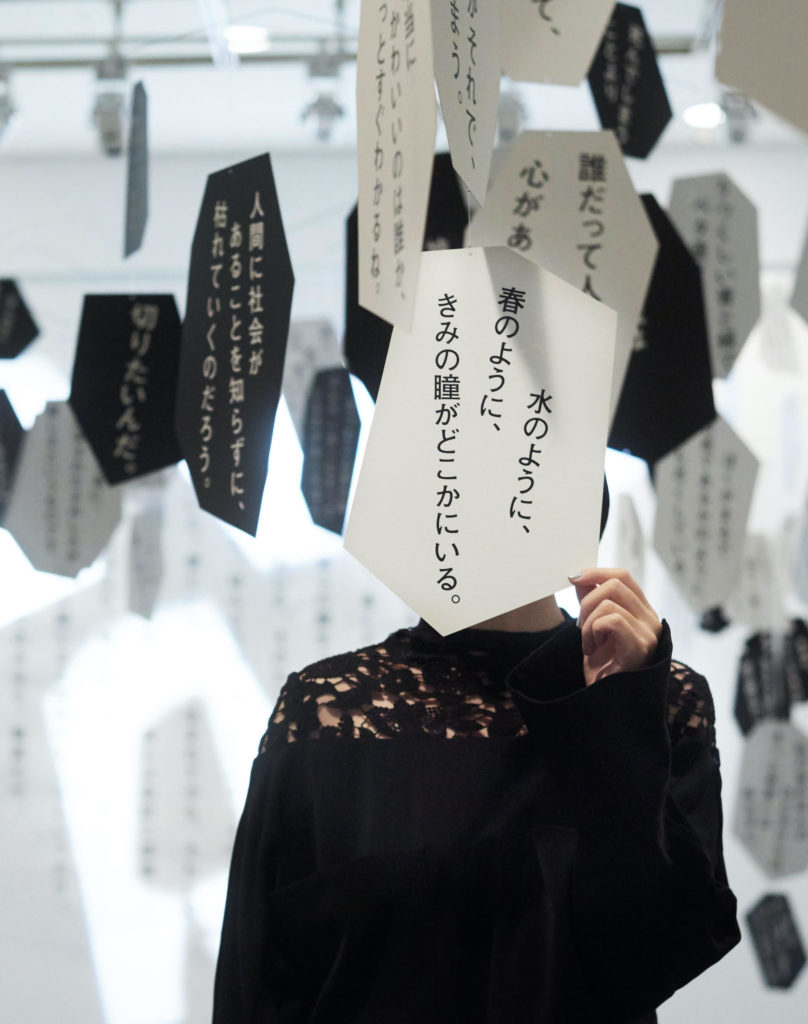

I used to think poetry was something people read in books before my solo exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of Art. I thought it was already complete by the time it got to the reader. So, I initially wasn’t interested in the idea of exhibitions. When they approached me to show my poetry at the Yokohama Museum of Art, I figured I should do something that could only be done in that setting instead of just exhibiting my poetry. I came up with the concept of visitors “completing” my poetry by physically standing there and decided to execute this idea through kinetic art.

I’ve always believed people apply their emotions or circumstances to whatever poem they’re reading at the time; the way each person thinks about poetry is different. In other words, the act of reading is active. It’s only natural for visitors to think “this is good” at varying stages while they’re at the exhibition. My poetry lives on in the visitors who carry my words after reading them. It exists through their interpretation. I wanted them to feel like they were actively seeking words on their own accord when they came to the exhibition.

——What’s behind the title, We are the 6th magnitude star of the night, born to keep this distance?

Tahi: I decided on this title last December. You might associate it with social distancing, but it bears no relation to that at all.

Whenever I write, I have one thought on my mind: it’s hard for all of us to understand each other fully. It’s hard because we exist as different beings from one another. This factor of “not understanding” is what makes us, us. I’ve had this belief for a long time now. If stars were on top of each other, then we wouldn’t have a constellation, yes? We see this colossal image in the sky precisely because the stars are far apart. Rather than strenuously trying to understand one other, I think it’s more beautiful if we all continue existing without necessarily understanding everything. That’s why I used this title for the exhibition.

——Art director Shun Sasaki designed the exhibition, yes?

Tahi: Sasaki-san gets the concept I’m going for, or why I want to make something, so the direction we work in is the same. I usually think of the concept and poems and leave the design up to Sasaki-san. He never fails to make something cool. I’ve added new work since the exhibition in Fukuoka, and some recent additions came from Sasaki-san. The poems that “loop” and the three-dimensional pieces were his idea, and he came up with these by taking my concept into account.

You can’t write good poetry if you think too deep

——How do you compose poetry?

Tahi: I try not to think too deep when I write poems. If I do, it ruins everything. It’s not fun to think of the punchline or a second line that explains the first line after being unable to come up with what to write. It lacks the element of surprise or unpredictability.

There are many cases where I can quickly jot down the first line with no force. And the rest comes easy. Other times, I end up with a decent opening line when I’m not even trying to produce anything — sometimes lines of poetry come to me when I’m on Twitter or writing some notes.

My poetry isn’t so much about what I want to write to begin with. Instead, I capture the surprise I feel when I come up with an odd or unusual line and channel that into poetry. It’s not like I have a particular message I want to communicate. Besides, there is no right way to read poetry. I think it’s rare for people to read my poems the way I had intended them to be read. But it’s interesting when people read them the unintended way because that’s up to their interpretation.

——My work requires me to write clearly, but it seems like the same doesn’t apply to you.

Tahi: I’m awful at writing explanatory essays. I say what I want to say before explaining something logically. I’ve been terrible at talking clearly or talking in a way that pleases others since middle school. Perhaps I started composing poems because I was insecure about not being able to explain things well.

——Have the words you use in your poems changed because of coronavirus?

Tahi: I haven’t made a conscious effort to change the words I use. However, I previously wrote a poem on masks, and the meaning of masks back then and right now is different. In turn, the meaning of that poem has changed too. But the definitions of words are continually changing regardless of coronavirus.

——I see. How about your motivation to create? Has that been affected by coronavirus?

Tahi: Normally, even when people are experiencing a similar problem, that problem affects people differently because of the environment they’re in. However, around April to May, it felt like people forgot about those differences on social media. Words that everybody could relate to became valorized. There was this pressure to say things everyone could understand. We all can share words, and in doing so, we’re able to discover things about ourselves that we previously didn’t know. But it was tough to do this around then.

On the other hand, if you enjoy poetry, books, films, and art, no one can take that away from you. During that period, it felt like people’s feelings about their interests were put in the center. It made me re-appreciate the time we had to focus on our passions. I’m unsure if “motivation” is the right term, but this feeling gave me the courage to host the exhibition and put out my collection of poems.

The undervaluing of “spending time to find your voice”

——On platforms like Twitter, you can say words could become the biggest weapon. What are your thoughts on how language is used on Twitter?

Tahi: When you see someone getting dragged through the mud, it could also make you feel some type of way. I think we’re susceptible to feeling angry towards someone after seeing everyone else get angry, even if we didn’t feel like that at first. When we catch feelings of disgust or contempt from others and use the same language as them, we lose our own opinions and thoughts somewhere along the way. Perhaps that explains why we forget that the person we’re targeting is just another human being behind the screen.

It’s necessary to think about what you think first. By disrespecting someone, you also disrespect yourself. Nowadays, spending time to find your own voice is undervalued.

But I mean, it’s challenging to figure out what you think when everyone else is saying something. There’s not enough time, but so much information. It’s easy to adopt someone else’s words and get on board with their opinions without thinking for yourself.

In terms of poetry, sometimes people recognize something about themselves through reading your words, even if you think nobody would understand. The feeling they get after reading a poem belongs to that person and that person alone, you know? I think that is such a sacred thing. I hope more and more people could tweet things of that nature; Twitter is a place where that’s possible, and I want it to remain that way.

——Last, what sort of people do you want to come to your exhibition?

Tahi: The exhibition is in Tokyo, and December is a busy time. You absorb so much information from billboards, stores, and sounds just by walking in the city. Everything, from advertisements to shop signs, is directed your way. Most people avoid these things and go on with their day. Plus, December is a hectic time when everyone starts talking about the next year. The days feel lighter and shorter. I feel like it’s also a time when it’s inevitable for people to be on the receiving end of words. Concerning the exhibition, I’ll be waiting for visitors that want to read willingly. When a visitor discovers my poems and finds something they appreciate, that’s when I know my words have reached them. My work becomes complete that way. Those who feel like they’re being washed away by the tide of words are the kinds of people I want to come. The poems are the polar opposite of the words throughout the city.

Tahi Saihate

Tahi Saihate is a poet and writer born in 1986. She received the Gendaishi Techo Prize in 2006 and won the Chuya Nakahara Award for her first anthology, Good Morning, in 2008. In 2015, she was awarded the Hanatsubaki Award for Contemporary Poetry for her collection of poems titled For Us, the Dying Kind. Tahi Saihate’s notable works include The Sky is Going to Splitand The Tokyo Night Sky Is Always the Densest Shade of Blue. Her collection of essays include Your Excuse is the Best Art and“Suki” No Insu Bunkai. She has also written novels such as Astral Season, Beastly Season, and Judai ni Kyokan Suru Yatsu Wa Minna Usotsuki. Tahi Saihate is also a lyricist. She is the co-author of Sennengo no Hyakunin Isshu, written with Asami Kiyokawa. The book is a modern-day translation of Hyakunin Isshu (a historical poetry anthology featuring 100 poems by 100 poets). Last year, she published a guide for Sennengo no Hyakunin Isshu called Hyakunin Isshu to iu Kanjo. In 2018, she took part in Art Museum & Library, Ota’s exhibition, held a solo exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of Art, and collaborated with HOTEL SHE, KYOTO on an exclusive room, “Poetic Hotel” the following year. She continues to work across a variety of fields. Yakei Za Umare (Shinchose Publishing) is her latest anthology of poems.

http://tahi.jp/

Photography Eisuke Asaoka

■Tahi Saihate, We are the 6th magnitude star of the night, born to keep this distance

Tokyo:

Opening period: 12/4~12/20

Venue: Parco Museum Tokyo

Address: Udagawacho, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 15-1 Shibuya Parco 4th floor

Opening hours: 11 am~9 pm

Holidays: None

Entrance fee: General admission: 800 yen, Entrance fee + mini book: 1,800 yen

https://iesot6.com

Nagoya:Opening period: 2/13~12/28 (2021)

Venue: Parco Gallery

Address: Sakae, Naka-ku Nagoya, Aichi prefecture 3-29-1 Nagoya Parco West building 6th floor

Holidays: February 17th

Entrance fee: General admission: 800 yen, Entrance fee + mini book: 1,800 yen

Osaka:

Opening period: 3/5~3/21 (2021)

Venue: Parco Event Hall

Address: Shinsaibashisuji, Chuo-ku, Osaka City, Osaka prefecture 1-8-3 Shinsaibashi Parco 14th floor

Holidays: None

Entrance fee: General admission: 800 yen, Entrance fee + mini book: 1,800 yen

Photography Yohei Kichiraku

Translation Lena Grace Suda