Today, staying at home is a part of everyday life, and various cultural activities have come to a halt. How would you respond to the question, “Is art nonessential?” Allow me to introduce an art project that raises questions against public opinion, now that conforming to social norms is prevalent more than ever.

I came across the plain-looking Shinkou Building in a small alley off the main street, two minutes away from Mitsukoshi station, Tokyo. The vacant property is going to be demolished two years from now. It also happens to be the venue for an art fair called Gallery of Taboo. Once you go to the third floor, a room covered in white punch carpet will greet you. This unusual space is where artworks artists display their work; one could regard the structure as a housing unit or a series of apartments.

The person hosting the exhibition is Shunichi Oda, the photographer who published Night Order, a photo book documenting Tokyo at night after the government made an emergency announcement last year. Why did he invite eight artists and work with locals to host an art fair- right when the government made another emergency announcement? I spoke to Oda and art director Koji Shiouchi (CATTLEYA TOKYO), who Oda teamed up with, to learn about how Gallery of Taboo came to be.

Connecting to society; spreading the idea of “for others”

—You published your photo book, Night Order, while we experienced our first emergency announcement last year. Can you talk about what instigated this art fair amid our second state of emergency this year?

Shunichi Oda (Oda): Around the time the government declared its first emergency announcement, I kept on asking myself if I could do anything as a photographer. I went out into the city, compelled to document the situation, and I spotted this bar I would visit a lot. The owner had made an impressive financial sacrifice by closing it temporarily. The desolate sight of shut-down bars hit me hard. But thanks to restaurants and bars making a sacrifice by shutting their doors, a different kind of calm and beauty were beginning to appear at night. I felt like that was what I should shoot and created Night Order. As someone who treats photography as a serious craft, I’m still embarrassed to show photos I take outside of work; it feels like I’m naked and exposing my inner self. Pictures I take for work are for business, in contrast to photos I take for art, which is for myself. I realized there’s a type of photography that’s not for business or myself but for others. I had this epiphany after I did what I could, even though it was a small act. I published the photo book alongside coupons for restaurants that I frequented often. Acts of kindness for people around you eventually lead to acts of kindness for society. I thought spreading the idea of “for others” could translate to photography for society. That inspired the conceptualization of Gallery of Taboo.

—How did your discovery of photography for society connect to the concept of Gallery of Taboo?

Oda: Looking down on society from a pedestal and saying, “This is the problem” in broad strokes is inappropriate and phony. Also, I grew up as a problem child, and I had this feeling that I was a minority, somewhere in the back of my head. Naturally, the notion of social norms and respectability never sat right with me. I wanted to convey my honest feelings towards society through photography because I portray my truth that way. I had this anticipation of going beyond the limits of my mind by making a project and collective. While I was entertaining this thought, this person suggested I hold an exhibition. I pondered on what I should do to connect with society and what questions I should tackle. And I ultimately arrived at the theme: Gallery of Taboo.

Brainwashing caused by the need to connect and the pressure to conform — updating the OS/heart

—Could you expand on what you mean by respectability not sitting right with you?

Oda: This is just my opinion: I feel like the internet has made it easier for people to connect, but it also has equalized values everywhere because of peer pressure. There are more rules now — telling people what’s permissible and what’s not — and I feel like we’re heading into a more restrictive world. On top of that, we’re overwhelmed with the sheer amount of information. We have a situation where more people download knowledge instead of searching for wisdom and understanding it. I think this is comparable to the brainwashing of the masses. For instance, in Japan, people regard marijuana as something illegal and therefore dangerous. But if you look at the States, it’s seen as a product that people enjoy and is legal in some states. Alcohol was illegal in America from the 1920s to the 1930s, but now it’s become something many people like and consume. If you think long-term, values and social norms change according to the times. These things are relative. I wanted to question norms and think proactively.

Koji Shiouchi (Shiouchi): Without deviating from Oda-san’s ideas, my concept as a creative director is to touch people’s hearts/OS. I think of the vacant property as the hardware and the eight artists as the software. I want visitors to access their senses once again since the emergency announcement made them numb. I hope they could look at their frozen OS and update it. The key visual for this is the traffic lights. Like how “what’s socially acceptable” changes according to the era, the Japanese understanding of “ao” (blue) equating to “correct” has shifted too. In Japanese, green things have traditionally been deemed blue, such as “aoyasai” (green vegetables), “aomono” (greens), and “aoba” (green leaves). Meaning, even though the green light is green colored, it’s officially called the blue light in Japanese. This relative correctness is a social construct and differs from factual correctness. This situation, where society accepts something factually incorrect, happens everywhere.

—Regarding questioning the norm, I feel like hosting the exhibition online was another viable choice. I’m interested in knowing why you decided to host a physical one.

Oda: This is something Shiouchi-san told me, but digital things are two-dimensional while real-life things are three-dimensional. Three-dimensional things have much more information, so I feel you could convey thoughts and feelings more deeply. People could fully appreciate many artworks in a real-life setting, such as ceramics, music installations, and photography. We decided to host a physical one so people could engage with the art sincerely. I knew we were going to get criticisms, but I was ready for it.

Shiouchi: Of course, we took measures to prevent coronavirus from spreading. Also, the quietness and coldness virtual mediums provide are effective at times. But we believed we could present our concept and enthusiasm honestly by talking to people using our actual human voices. Ideally, I could make something that represents reality as a four-dimensional thing by using technology while comparing that to a five-dimensional prallel universe.

People connected by serendipity

—There’s a disharmony between a normal-sized, everyday building in Nihonbashi and the art displayed there. Was this intentional?

Oda: If someone wants to rent a gallery and have an exhibition there, then a gallerist could do that. When I thought about why this art fair was necessary, I figured we needed to work together with the community. So, the location was crucial. By hosting an art fair, people who never set foot in Nihonbashi could visit and contribute to the local economy; the profits would go to both the artists and the city. I thought it could bring positivity to the locals and the people around us. And I thought it would be fun if unexpected interactions between such people took place. That’s why I decided to rent an unused building in Nihonbashi, which was financially devastated by the pandemic, and turn it into an alternative space*. People have used the term alternative space as something in direct opposition to its surrounding spaces since the 70s. I wanted to subvert that and create a space that coexists with the local area and upgrade the definition to the modern version.

*Alternative space: a space used for purposes aside from its intended purpose. Artists living in New York in the 70s used properties in this fashion, which amassed into a cultural movement.

Oda: I looked for a place for the exhibition for three months because I didn’t want a venue with just a regular flat surface. I preferred the artists to feel like they could express their art according to their given space. I made phone calls, looked up registrations, and met up with the owners directly. But I was told that they couldn’t rent it to me short-term or that they had found someone already. I couldn’t find anything and was about to give up. Just then, my friend from my student days introduced me to Mizobata-san, the architectural director of NOD and owner of GROWND nihonbashi. After that, I got introduced to someone from Mitsui Fudosan, which led me to Shinkou Building. I met other people on the team, thanks to fate. Kohei Kikuta and Yuzuru Murakami of Buttondesign directed the design of the space. They came up with the idea of covering the insides of the worn-out building with white carpet and placing images of famous western museums on the walls. The aim was to have upcoming artists question society’s idea of correctness and show their art against a backdrop of established, acclaimed art. The space itself asks, “What is correct?”

Shiouchi: Oda-san himself is like a junction that connects people. I fused his role and presence into the key visuals. People say ideas and movements are in proportion to one another, and I think he came across the perfect venue because the act of him going back and forth served as his guiding compass. The color white, seen in Kikuta-san’s conceptualization of the space, ties into each artist’s artwork. The color complements the overall art. “Fake museum” is the space concept- the virtual images of western museums printed on tarpaulin and the stark, fluorescent lights greet visitors. This witty style was effective in communicating the artwork.

To create, look, sell, destroy, and so on. Are we content with the current landscape of art?

—How did the collective of the eight artists come about? Did you have any criteria?

Oda: Someone who’s uncontrolled by economic reasoning or rationality. Someone who does the unexpected. Chaotic. Those of us who curated this exhibition aren’t gallerists, so I didn’t want to be too strict about who to bring in. I met artists and other staff who related to the concept by chance. Much like a jazz session, we got a result that no one could’ve predicted. To move people, you must present them with something different. If you don’t see the things other people don’t see, then you can’t make something new and touch someone’s heart. I think those who say things that other people can’t understand are interesting. This applies to Shiouchi-san too, but such people look at society from behind or the left or right side — they dig up information from multiple angles. Whether or not what they find is the truth doesn’t matter for a moment because what matters is the ability to look at the world in multiple ways.

Shiouchi: The gallery became an intersection for collectives and otherworldly creators to come together. We tested out a hypothesis with this exhibition, like chaos engineering, and we still came across unexpected encounters and bugs and chemical reactions.

—Sound art, ceramics, performance, photography, tattooing, Kinbaku- It seems like each artist’s take on the relationship between people and art differs quite a bit.

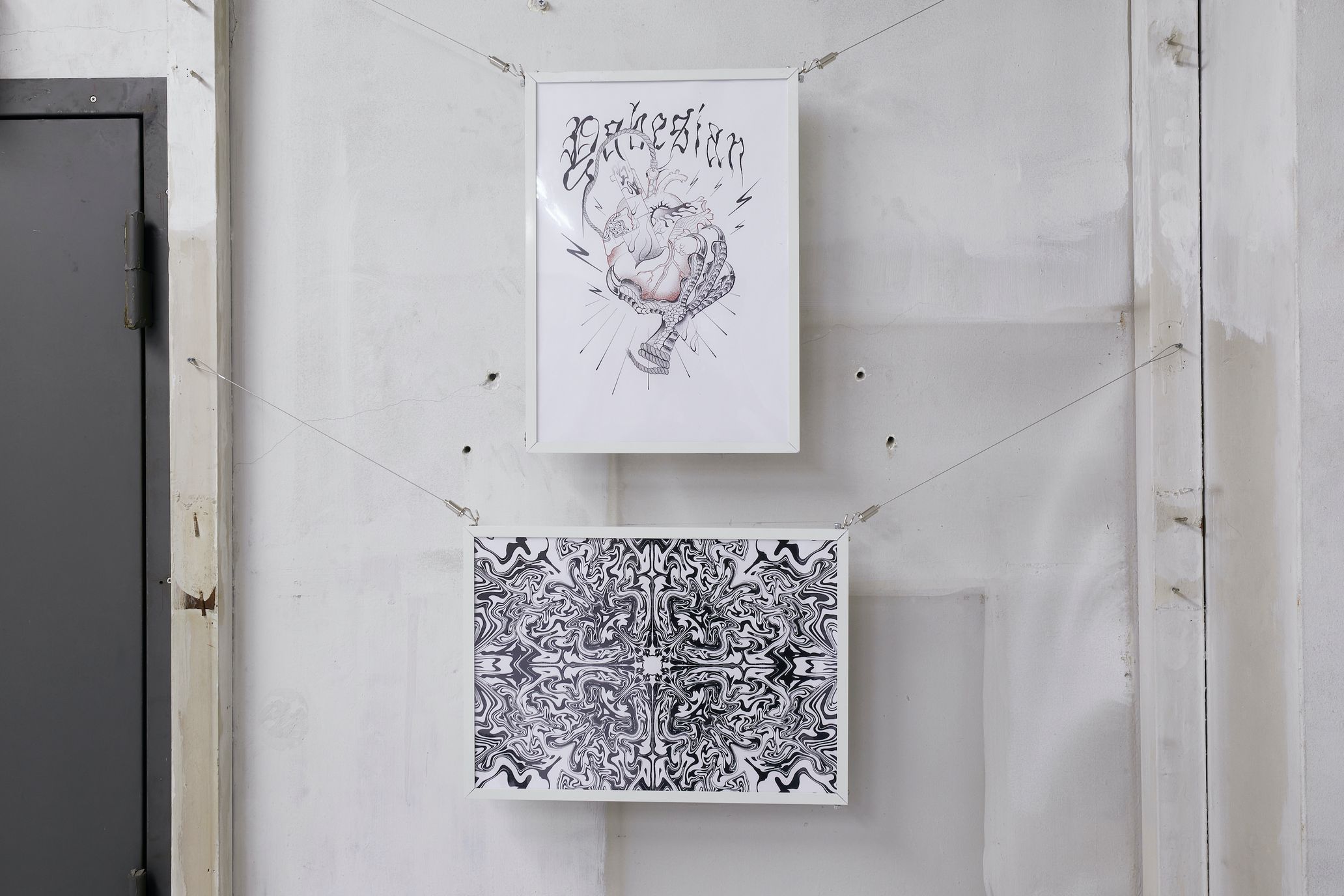

Oda: The visitor could access history through one used book from Komiyama Tokyo, and they could also buy art from A2Z™, whose art is edgy and contemporary yet beautiful. In contrast to that, Boring Afternoon didn’t make artwork for the occasion because they live and create art with those who come to the exhibition. TEMBA destroys art in each room. Kaito Sakuma A.K.A Batic vibrates space while Satoshi Miyashita’s ceramics stay still. From conventional art forms like photography, all the way to avant-garde, contemporary art — artworks that would usually be separated coexist together here. To create, look, listen, watch, buy, destroy, sell, not sell… people’s relationship with art, or the way they treat it, should be up to each individual. You could consider something as beautiful and nothing more, for instance. I hope people could ponder in the gray area, the in-between where there’s no right or wrong.

Shiouchi: As art evolves and becomes more commercialized today, the consumer’s role is more imperative than ever before. We can’t deny that the context of art is becoming more complex. Gallery of Taboo exists in opposition to the insular, contradictory, and cursed art industry, where people use jargon to keep their world closed off. It’s also in opposition to those who praise limited methods of creating art.

Oda: We can have both visually stimulating art and intellectual, conceptual art. Like, does it bring you joy? What do you feel?

(Front) Satoshi Miyashita, “∞” — The insides of this piece are the main attraction. The statue with the “sky” inside its head is based on themes of meditation and prayer. Once visitors look inside the hole, they’ll see another version of the statue, which imitates the experience of looking at one’s inner, imaginary universe.

The necessity of trusting one’s imagination, dialogue born from restrictions

—As the organizer of Gallery of Taboo, what does the medium of photography mean to you?

Oda: There are less freedom and information with analog media among the vast sea of other mediums. I feel like it’s close to haiku poems. Although you can frame the time and background, viewers usually create their interpretation with the limited amount of information they’re given. There’s a high possibility the viewers will interpret your work in a way you hadn’t intended. I think haiku is still relevant today after all these years because it links to the power of imagination, which relates to the infinite universe itself. Matsuo Basho’s “The Cry of the Cicada” probably sounds different according to the times. People might also picture varied imagery in their minds according to the time they live. That power of imagination sublimates his work. Perhaps I say this because I lack confidence, but I believe photography is the art of imagination. It’s an art form that needs other people’s help for it to be complete.

—Lastly, as different relationships bloom between society and art, and art and people, I think this exhibition will become a new point of contact for visitors. With Gallery of Taboo in mind, how do you think the role of art will evolve?

Oda: I believe the sincere role of art is to raise questions. Art expands people’s possibilities. It’s essential because it supplies meaning. There’s this legendary photo magazine called Provoke, the “provocative materials for thought.” It was launched in 1968 — so around 50 years have gone by since then — but when I saw photos by Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahara, I was blown away. It was like I was being asked, “Are you living life to the fullest? Are you searching for the possibilities of art?” It told me, “Live life, madly.” Of course, this was just my interpretation, but that was the intense message that lingered in my mind. I even felt self-loathing because it made me feel lazy and wrong. I think there’s the danger of feeling doubts about society and oneself and pretending to not notice one’s true feelings because of one’s circumstances. I want people who feel down in the slumps or people who feel trapped but desire to make a breakthrough to come to Gallery of Taboo. I want them to be blown away from the brilliant artworks, ruminate, and expand their potential, just like me. Art is salvation.

Shiouchi: There’s a term called social sculpture, coined by Joseph Beuys, which is also A2Z™’s concept regarding his work. The theory is about how every single person is an artist. It’s the artistic idea that each person’s actions can contribute to the overall happiness of society. It would be great if art or the exhibition could enable people to think about what they can do in this situation- now that we need to stay home more and limit our activities. Some call it the butterfly effect, but group mentality is so powerful. All it takes is for 10,000 people to cause an earthquake. The power of individual consciousness is intimidating. But it also can make the world a better place if each person acts and expands their mind. Isn’t it critical to live in the now by imagining a new, unknown landscape of the city?

Now that staying at home is the norm, many cultural activities and events are dwindling. I haven’t gone to museums or movie theaters in a long time. I couldn’t answer the question, “Is art nonessential?” right away when photographer Shunichi Oda asked me. My life won’t be affected negatively, even if I don’t interact with art. When I entertained the thought, I realized I had never questioned my thinking about art being essential or nonessential. Without investigating the meaning of art, I had unconsciously decided what makes something socially acceptable. Gallery of Taboo is a mirror that reflects our thinking and social etiquette and is a shelter that embraces doubts. In a world where new restrictions and norms are being invented, dialogues in the gray area are what we need. The exhibition is open until February 28th.

Koji Shiouchi is an art director, graphic designer, and founder of CATTLEYA TOKYO, born in Aichi prefecture in 1985. After studying in the U.K., he earned a visual design degree from Kyoto Seika University. He founded the creative collective CATTLEYA TOKYO in 2013. He works as an art director, graphic designer, and video maker in various fields such as art and fashion, with his unique vision. He had an exhibition in September 2020 at OIL by Bijutsu Techo.

http://cattleya-arts.com/

Instagram : @cattleyatokyo

Shunichi Oda is a photographer born in 1990. He went to the U.K. in 2012 and studied photography on his own, and became independent in 2017. In 2019, Shunichi Oda joined symphonic. He mainly shoots portraits for magazines, advertisements, and more. He published Night Order, a photo book depicting Tokyo’s cities at night during the emergency announcement in 2020. He hosted Gallery of Taboo in 2021 and released “OTONAsei – Hyakumensoka Suru Jikoishiki no Hateni.” He gets his ideas from his connection to society and is working towards producing socio-photography to inspire people.

https://www.shunichi-oda.com/

Instagram: @odaoda_photo

■Gallery of Taboo

Location: Chuoku, Nihonbashimuromachi, Tokyo 1-5-15 Shinkou Building 3rd floor ~ 5th floor

Date: January 14th ~ February 28th, 2021 (closing day extended until February 28th)

Opening hours: 1 PM ~ 8 PM (on the last day, last entrance is 30 minutes before closing time)

Holidays: No holidays

Admission fee: Free

In cooperation with: Nihonbashi Restaurant Association/GROWND nihonbashi

Instagram: @gallery_of_taboo

*The first 500 visitors will receive a 500-yen coupon, available to use at around 300 restaurants in the Nihonbashi area, thanks to Nihonbashi Restaurant Association/GROWND nihonbashi. Half of the profits made at the exhibition will go to the local economy. This way, visitors can contribute to the city’s livelihood. galleryoftaboo.com/

Photography Shintaro Ono