Joe Brook talks a lot and smiles a lot. And he always has a camera hanging from his shoulder and looks through its lens. Perhaps most photographers are like that. For me, the embodiments of this are William, the rock music journalist and protagonist of the film Almost Famous, Saul Leiter, the late New York photographer behind the photo book Early Color, and Joe Brook.

He looks good with a camera. Whenever I meet people like that, that fact alone makes me so happy. Moreover, Jason Lee, one skater Joe admired, is also in Almost Famous.

©Joe Brook

Those on the cusp of the transition period like both film and digital photography

Digital cameras are very convenient. That’s even more apparent in skateboard photography. You can check if you’ve got the necessary skate shots on the spot, like the way a skater flips their board or does tricks. You can also check if the focus and lighting are just right as well. Further, you don’t have to worry about costs when you take photos that require many sequences of shots, such as complex tricks. You can take as many photos are you want.

However, that wasn’t the case in the 90s. Wasting film rolls in the blink of an eye was an everyday occurrence. You had to develop the photos at a photo lab to look at what you shot. It wasn’t uncommon for photographers to apologize to skaters after being shocked by the finished product. In Japan, we were the first to introduce Polaroids for test shoots with skaters. At WHEEL, the only Japanese skate magazine back then, we used our budget to the full extent and invested in skate shoots without being frugal. We even provided passionate amateur photographers free rolls of film. There were similar cases in America, the leading nation in skating.

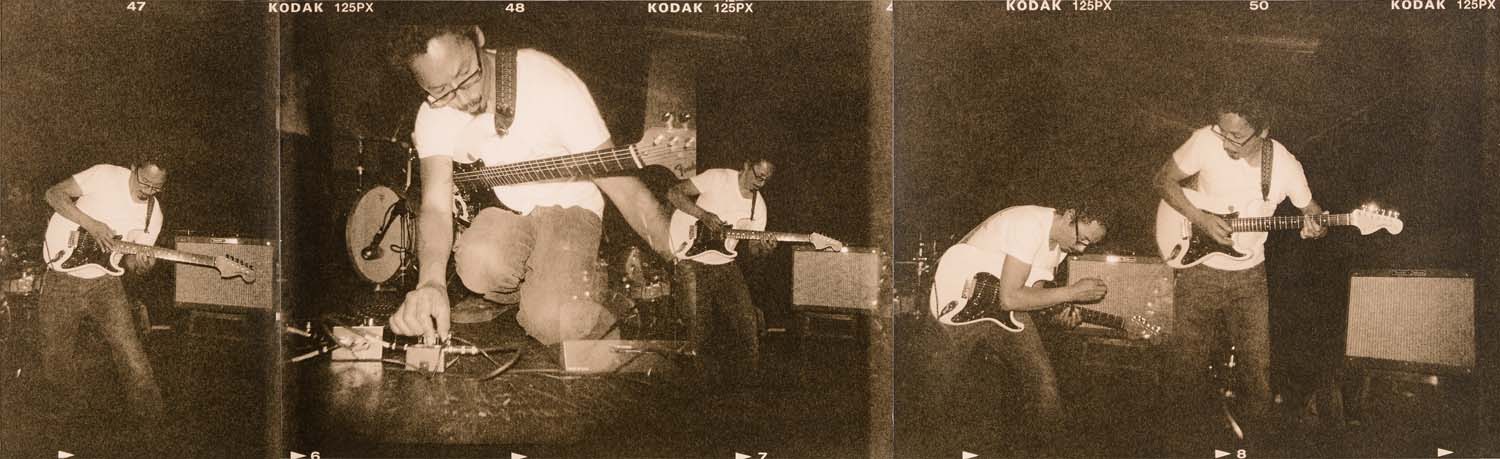

Everyone was serious about film skate photography, both technologically and financially. Skaters wanted to get sponsored as soon as possible so they could focus on skating. Photographers strived to make their name known to gain a stable budget and shoot more skaters. However, regardless of how much money they had, real photographers continued to take and enjoy pictures. This spirit is akin to skaters who liked skating in their beaten-up skate decks and slip-ons with holes, regardless of the pain they felt when they slammed and whether they had a sponsor. Joe Brook was one such photographer and skater.

©Joe Brook

©Joe Brook

Building a resume in photography through tenacity

Before Joe turned 20 years old, he moved from his hometown of Detroit to San Francisco. Back then, he was a skater, not a photographer. He only packed a duffel bag, a skateboard, and 500 dollars. Joe scraped by on several part-time jobs and immersed himself in the mecca of skateboarding. He befriended people like Greg Hunt, who later became a photographer, and Dave Metty, who worked at the skate company Deluxe Distribution. Because Joe skated relentlessly, he naturally met star skaters like Jim Thiebaud and Tommy Guerrero. Right when he started to up the ante as a skater, he got injured badly. Joe had to give up on his dreams of becoming a professional skater, but he still had a desire to express himself, and so he embarked on the path of photography.

Photographing and developing film. It didn’t take long for Joe to become hooked on these things. Since he got his start in photography, he took pictures as if something came over him. Whenever Joe had the money to buy dinner, he would spend that on developing photos. And he traveled when he had the chance. It was Gabe Morford who took pictures of famous skaters in San Francisco at the time. Joe went to High Speed Productions, which publishes Thrasher, Slap, and other skate magazines, to show his photos. Lance Dawes, the then-editor of Slap, showed him the ropes. Joe received tough lessons, starting with focusing his lens, finding the [right] distance between the subject, composing [the shot], and so on. After Lance would go hard on him, he would give Joe several rolls of film and words of encouragement. He strongly wished to learn more about photography and to take ideal pictures. This mentality is everything.

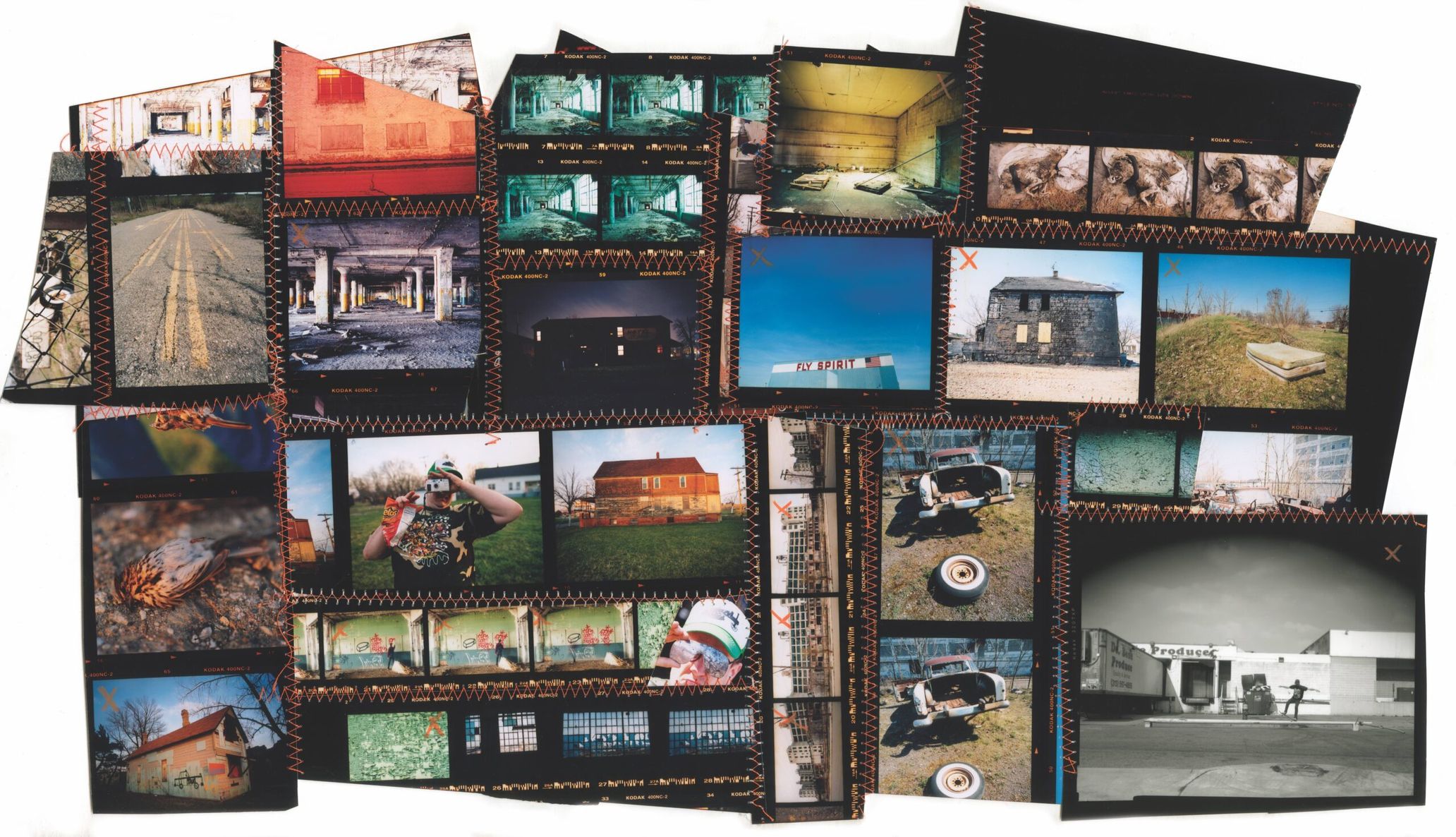

After that, he went on a 52-day skate trip and also couch-surfed throughout Europe for two months. He continued taking photos and developed a surprising amount of film at the lab. Joe then became broke, but he persisted and took pictures. There was no way he could stop; that’s the type of photographer Joe is. He was probably becoming the photographer he is today during that time.

©Joe Brook

A universal testament of skate tricks

When he was having fun dealing with his colossal amount of film at the lab, the then-editor of Slap magazine Lance contacted him: “You have good photos at that lab you spend all your money on by now, right? When you come back to San Francisco, bring those to the editorial department.”

This marked the beginning of Joe’s new journey. Lance and Mark Whiteley, who became the chief editor after, looked at Joe’s body of work. Once they did, they formally offered him the position of a photo editor. His answer was yes, of course. Two decades since then, Joe’s still active as ever. Also, he doesn’t only shoot things pertinent to skating.

I want to let it be known that he can find the best angle at skate spots. After he photographs them, the skaters go on to have thriving careers. Sometimes, the shots he takes become iconic. Skaters around the world talk about and share his work like, “That skater did that trick at that place.” Joe can take such photos, and he’s at the forefront of the skate scene as a photographer.

A guerrilla shoot at Hollywood High School in the middle of Hollywood is one example. A crowd formed when they heard the slamming sounds of a skateboard. He didn’t have much time until he would get kicked out. Under such circumstances, Joe shot Enzo Cautela, a pro skater from Enjoi, a skate deck brand, doing a hardflip. His shot of Enzo became widely known among many skaters in an instant. Going on a trip with Joe or getting shot by him is a massive opportunity for skaters. It goes without saying that for him, shooting is a total treat. I want to say the following to Japanese skaters who plan on traveling to America: “If you meet Joe, be proactive in a polite way. If he shoots you, don’t hesitate to create your original skate tricks.” If you could come up with amazing tricks, he will raise his right hand and smile as he looks into his camera.

©Joe Brook

Life is short—That’s why you document glorious events and skateboarding moments

The mecca of skateboarding. The metropolis of skateboarding. San Francisco has a distinct culture, separate from other skate meccas like New York and Los Angeles. A lot of physical skate media from the 90s have been discontinued or moved to a digital format. But if you look at Thrasher from San Francisco, you can tell that it’s still going strong. Another subcultural magazine they publish, Juxtapoz, is going well too. Places with a media presence that covers the scene properly are places that continue to inherit culture. That’s why San Francisco is a city where new talent is born and skaters release content endlessly.

Starting with Gabe Morford, who I mentioned, there have been excellent photographers in San Francisco like Pete Thompson, who published a photo book titled ‘93 til last month, and Ken Goto. But I love Joe Brook. Usually, human relationships improve every time you meet someone after getting a first impression of them, or a rift could grow increasingly. However, this doesn’t apply to Joe. One summer during the 90s, when there were no signs of digital cameras being the norm, I met him at the editorial office of High Speed Productions. My image of him hasn’t changed since. It’s like he’s been smiling from the first time I saw him smile. He’s a good guy and takes loads of pictures. Even today, where some Japanese people, who looked up to his work and used to take skate photos no longer do so, Joe continues to shoot. Of course, he takes other photos: artistic monochromatic panorama photos, beautiful landscapes, and cool portraits that disregard the [notion of] focusing on something. But he’s more of a skater than an artist. And a photographer. How can I say this? He’s like a lovable photo freak.

You know how professors like Doc from Back to the Future have screws or calculators falling out of their pockets every time they walk? You know how jazz musicians who play swing and have jam sessions drop cigarettes and matches when they order a beer at the bar? Likewise, I imagine him as someone with 35mm film and a magnifying glass sticking out of his jeans or Dickies. He looks for the perfect moment and skate spots 24/7. I love skate photos taken by people like him.

Digital cameras are handy today. But from time to time, Joe still uses a film camera to document important moments. As someone who isn’t necessarily a geek about equipment, he tries to shoot in natural light as much as possible. He likes to take on different challenges with the light, which changes every day. Like the protagonist of Almost Famous, rock music journalist William, Joe always has a camera hanging from one shoulder and takes in his surroundings with a grin. Not a single second goes unnoticed by him. Even if it did, he’ll probably laugh heartily and say, “Damn it!”

Joe Brook

Photographer from Detroit, Michigan. After graduating from high school, he moved to San Francisco. While skating with legendary skaters, he studied photography at an art school and from Lance, the former editor at the publisher, High Speed Productions. Afterward, he became the appointed photo editor of the skate magazine, Slap. He currently works across different media like the iconic Thrasher at High Speed Productions.

Instagram:@photojoebrook

Translation Lena-Grace Suda