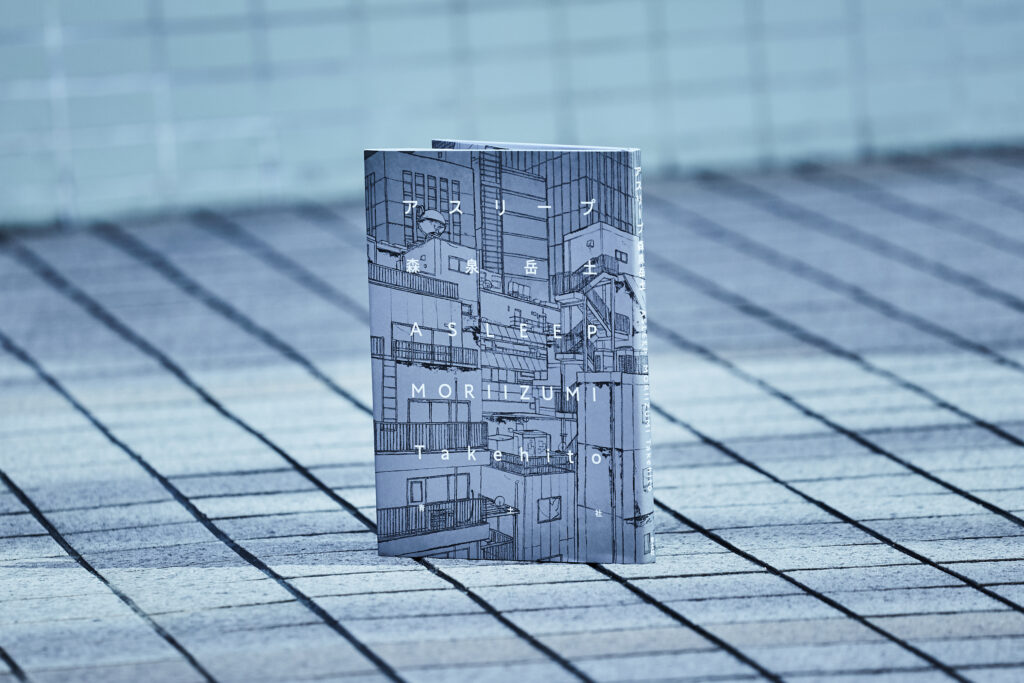

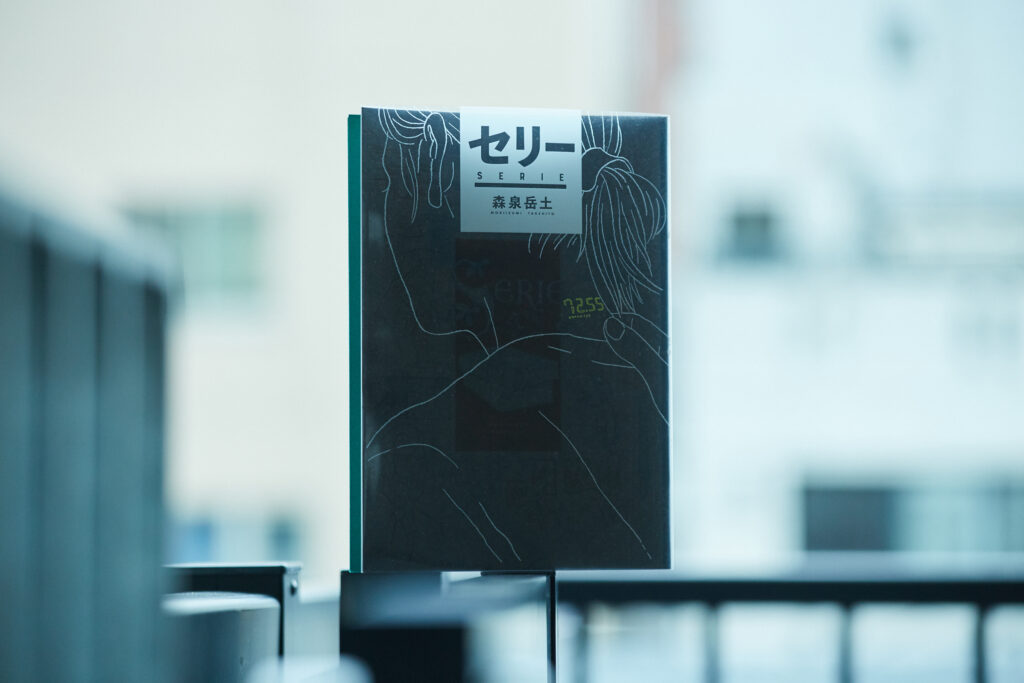

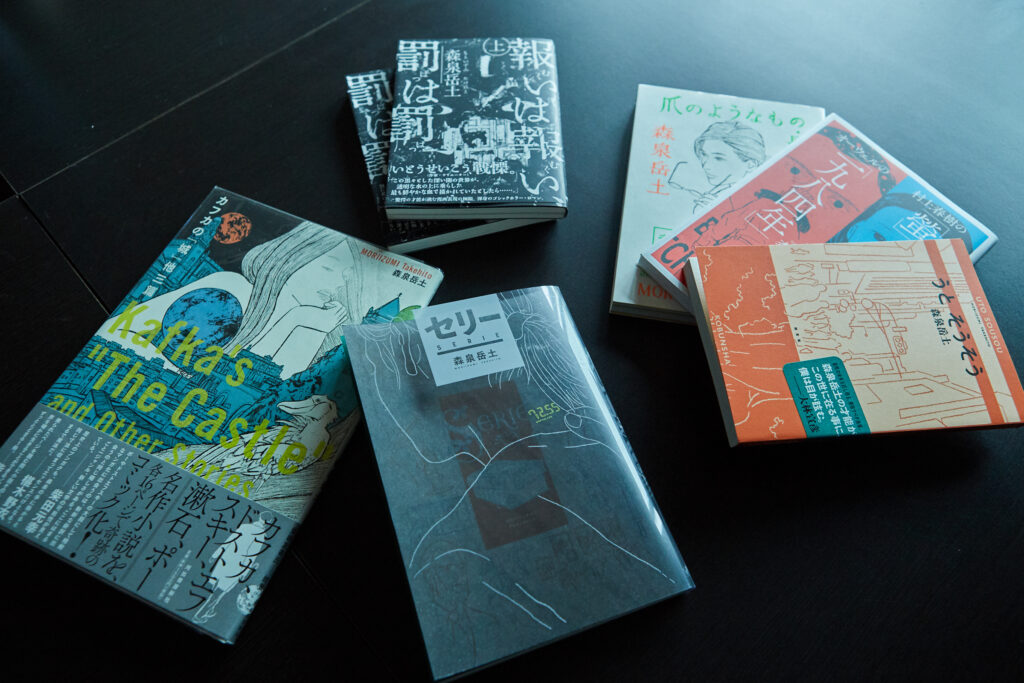

Water and calligraphy ink, detailed lines spawned from the technique using a toothpick, epic portrayal of the sceneries, and literary and poetic words—Mangaka Takehito Moriizumi deftly concocts these elements to construct unique worlds we see in his works. A tale of a mysterious adventure of a man and a woman who meet each other in a dark eerie night, Yoru Yoru Soba ni (2014, published by KADOKAWA), a gothic horror story of atrocious events happening in an old western mansion, Mukui wa Mukui, Batsu wa Batsu (2017, published by KADOKAWA), and a sci-fi piece that conveys a human and a humanoid spending their lives together in the impending end of the world, Serie (2018, published by KADOKAWA), are among the many of his original works he has written so far, and he also reproduces renowned works of literature by eminent names such as Haruki Murakami, Franz Kafka, Fyodor Mihaylovich Dostoevskiy, into mangas; ever since his debut, he has been excavating new potentials of manga. This month, Moriizumi has published his new masterpiece, Asleep (published by Seidosha), after a year since his last work, Something Like a Fingernail and Other Stories (2020, published by Shogakukan). The latest work is post-apocalyptic sci-fi that is staged in a world identical to that of Serie. We sat down with Moriizumi and talked about the origin of his new work, the outset of its theme etched in the story, sources of his creative philosophy and imaginations, and the renowned writer, Haruki Murakami, who is the impetus that led Moriizumi to pursue his career as a writer.

Double meanings of being confined in a cage

――Can you tell us how you started writing the new manga, Asleep (Published by Seidosha)?

Takehito Moriizumi (from hereunder, Moriizumi): The beginning was last year when the person from the publisher who was working for Mr.Junichi Konuma’s book, Shippo ga Nai (published by Seidosha), for which I provided the illustrations, kindly told me that they wanted to publish my book. In the beginning, I was planning on casually writing a fantasy, but on second thought, I figured it wasn’t appropriate to write a dreamy fantasy as we’re now living in an imminent reality and decided to switch to sci-fi that is somewhat relates to the reality and the future. Also, ever since I wrote Serie (published by KADOKAWA) in 2018, the vibe of its world has remained in me, so I thought I’d want to write something that would be like a prequel to Serie.

――Can you tell us a bit more about what that vibe of Serie is like?

Moriizumi: The characters I draw often come alive in me, but with Serie, it was my first time experiencing “the worldview staying alive in me.” In Serie, for example, if it’s something that carries on human culture and spirit, I think a humanoid should also be deemed as a human, and we should be more positive about it. I guess, the story proposes the question of what humans are. Though, it’s also at the borderline of showing disappointment in humans, but still makes us want to seek hope in them. Ever since I wrote Serie, I’ve realized that I’m managing to live life with hope even in this risky world; the worldview of Serie is well linked to my feelings in real life and continuously nurtured in Asleep.

――So, that means Asleep was influenced by living in the society with Covid. I assume your workstyle as a mangaka hasn’t changed much from before the pandemic, but do you think your lifestyle has changed?

Imaizumi: My normal lifestyle hasn’t changed much, but I do get the feeling of being cooped-up. Although I’m essentially an indoor person, I can acknowledge the huge difference between a circumstance where you’re staying in because you want to and a circumstance where you aren’t able to go out even when you want to. I also mentioned this in Asleep, but we’re all trapped in two different ways: One is, space wise, we are forced to self-quarantine at home. And the other is, time wise, our futures aren’t guaranteed. To be more specific on the latter point, I couldn’t write a dialogue like, “let’s hang out tomorrow,” or “let’s go somewhere next week,” at least right when I was creating the story, because we’re basically trapped in the time of “now.” There is the past, there is now, but we still don’t have the future.

――For me, the most impactful part of Asleep is the depiction of the protagonist, Chitaru, being left alone in a Metropolis and consumed by feelings of impotence.

Moriizumi: That’s actually how I was feeling in real life. Perhaps, people have a natural inclination to think that humans have to move forward and act to make the world a better place. My overall image of life is walking forward to reach the top of a mountain while looking at your feet, but since you have to watch your feet, you wouldn’t know what to do if you’re commanded to go somewhere else. Asleep embodies the reality in any way, so the part you mentioned is also linked to the reality.

The poetic sentiment (Poesy) spawned from blank space

――The story of Asleep takes place in a post-apocalyptic world, but it’s not conveyed like a world of post-nuclear war in the 20th century. It felt incredibly realistic how you portrayed the world’s end, “as if the world is slowly passing away.”

Moriizumi: Perhaps, I didn’t want to draw the moment of the world being obliterated. It’s because those types of scenes could be somewhat cathartic. It’s like there’s a certain delectation in catastrophic portrayals, and I thought if I put all the joy in the beginning and tried to make room for more twists, the rest would merely be updates about what’s happening in the world in the story. I do have my own scenario of how the world ends in Asleep, but I wanted to only portray the world after things had happened—so, I only focused on drawing the things that exist after the apocalypse. My image of the world’s end is not so dramatic like with nuclear war; to me, destruction is something that comes creeping from behind.

――While feeling trapped, Chitaru finds potential that changes her perception of the world. Is this mirroring the way you see the world?

Moriizumi: Having potential means that there’s hope. I personally don’t want to feel despair in any circumstance. In fact, the character is about to succumb to despair, but I wanted to convey her clenching her teeth and moving forward towards hope.

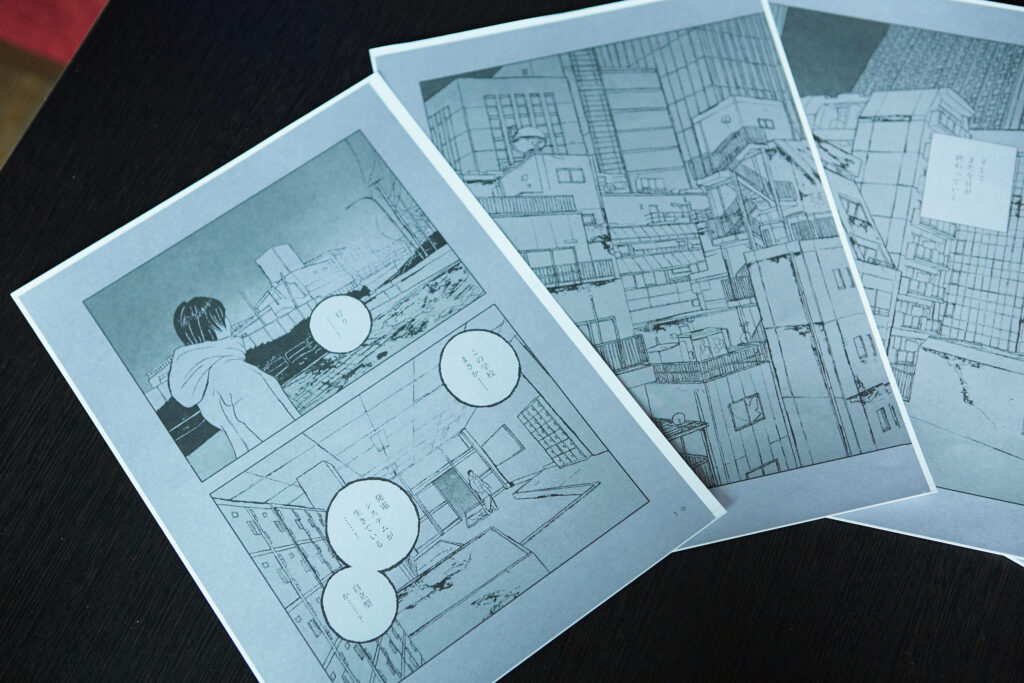

――In the early days, you were saying that you didn’t want to write tales but rather want to write stories that are like poetry. And in a certain degree, Asleep feels like reading a long poem.

Moriizumi: It in fact feels like it. I’ve always wanted to write a manga embodying the sense of spaciousness you would feel in poems. In the old days, I had been drawing characters in silhouettes for a while. By not drawing their details like their facial expressions and clothes, I was trying to create the “spaces between lines.” Specifically, for example, if I drew a sad face on a character, it’s simply going to show that “the character is sad.” But, because human emotions are more complex in nature, I had deliberately drawn the characters in silhouettes, so that the readers could imagine freely their faces and feelings. As I cut my teeth as a mangaka, I’ve acquired other ways to create a sense of spaciousness, instead of doing it in an extreme way like I used to.

――I can tell that the words were chosen very carefully, and fewer words were used.

Moriizumi: I’m the type who likes to keep things minimal. Initially, there were 3 or 4 times more words I wanted incorporate in Asleep, but I took them out as much as I can and kept only the ones that are truly essential for portraying the story—it was like a constant task of subtracting from the stock of words. It’s interesting how each word that remained in the story start harnessing richer “meanings.” So rich that they fill in the gaps between the lines. The same thing can be said with the frames—I want to make frame layouts minimal as I can to construct a good rhythm of the story. In manga, a good rhythm is a paramount factor that allows readers to read without a hitch. I’m very particular with frame layouts and I redo them many times thinking like, “I should place a quiet frame here” or “I have to add a speech bubble in this frame.” So, every frame is there for a reason, and I would never put a picture or a word that is insignificant. But at the same time, I need to make sure that I’m not forcing any rules on the readers and there’s enough leeway—And now you know, that’s where I let my skills shine [laughs].

Cultivating the ideas of the worlds in the stories through my time alone

――I’ve noticed that “the night” seems to be a consistent key motif in all of your works. I assume that it’s the mainstay of the world depicted in your works, but can you elaborate on this?

Moriizumi: Well, actually, it’s because I simply love the night [laughs]. I like to go on a walk at night. I can’t really explain why I like the night so much….

――Is it maybe because you become more creatively active at night?

Moriizumi: I’m not sure. I’ve liked the night since I was little. And I’ve been going on a walk at night since I was a kid. Maybe it’s because the night gave me my time alone. You know, when you’re a child, there’s always a lot going on around you, as you’re always surrounded by someone like your parents or siblings. I was always seeking to escape for a bit and knew that solo time was crucial for me. I used to take a walk alone along the riverbank at night, feeling a lot of room to breathe. So yeah, being alone when you choose to be alone feels wonderful. And I feel like the same thing can also be said for when reading a book.

――That’s true, parents would often leave you alone when you’re reading a book.

Moriizumi: That’s right. I feel like I’m able to breath when I’m reading a book. I didn’t like exams or studying in general, and I didn’t have a good social life, so a walk at night and reading a book was what made me feel alive. These two things were boons to my life—the biggest boons.

――So you liked reading since you were a child?

Moriizumi: Yes, for as far as I can remember. When I was little, I was reading children’s novels like The Chronicles of Narnia and Treasure Land. The first manga I ever got into was Father and Son (by e.o. Plauen.) I read only the books I wanted to read and never read the ones my parents bought me [laughs]. I was adamant when it came to books. Especially since the act of “finding books for myself” was also a significant part of my reading process. I guess I was desperate to establish my own realm with only the things that I chose for myself. I started off from reading child-detective books, and by the time I was in middle school, I had finished reading all the books by Agatha Christie; I also liked John Dickson Carr books. I hadn’t read much sci-fi stories, but back then, I’d read all the books written by Shinichi Hoshi.

――In your interview, you were saying that after you’d read many books of different genres, you were shocked when you first read Soseki Natsume’s novel, as the ending was so punchless.

Moriizumi: I was so shocked, indeed. My reaction to the ending was like, “wait! Is that it?!” [laughs]. I think the first Soseki Natsume book I read was Sanshiro. The story ends repeating, “stray sheep, stray sheep” and that’s it. It’s not like a detective novel where a culprit is caught in the end, or a happy-ever-after like in children’s novels, and I was just so appalled. Afterall, I was left with this intangible feeling that bottled up inside of me while reading the story and had to deal with it little by little each day. It felt like the rug was pulled out from underneath me [laughs]. It also felt like the story handed me something important…like an important homework of my life. In fact, that’s where my definition of “literature” came from.

――Would you say your view of literature serves as the basis for creating worlds we see in your works like Serie and Asleep?

Moriizumi: Hmmm, I’m not sure what is at my core…. But like you were saying, I wasn’t influenced by manga much, but I was unequivocally influenced by novels. Novels give you way more chances to use your imagination. Again, I guess I genuinely like the process of filling in blank spaces and spaces between lines. There’s always a “discovery” to it. It eventually leads to discovering yourself through stories. I think exploring and finding the unknowns is one of the lavish experiences in life. There are people on one side who likes to resonate with others and say, “I feel you!” but I’m more of a person on the other side, who finds joy in finding new things and be like, “that’s a discovery!” I want to write mangas that give opportunities for readers to fill in blank spaces and discover about themselves. What’s great about manga is that because of the illustrations, you don’t need a lot of words to explain details, or you can use words to complement the illustrations—basically the story can be told through “inadequate” illustrations and words. And the sense of spaciousness is born through these imperfections. It allows the readers to use their imaginations. Considering so, I think manga has infinite possibilities for us to explore.

Haruki Murakami novels that helped me grow up

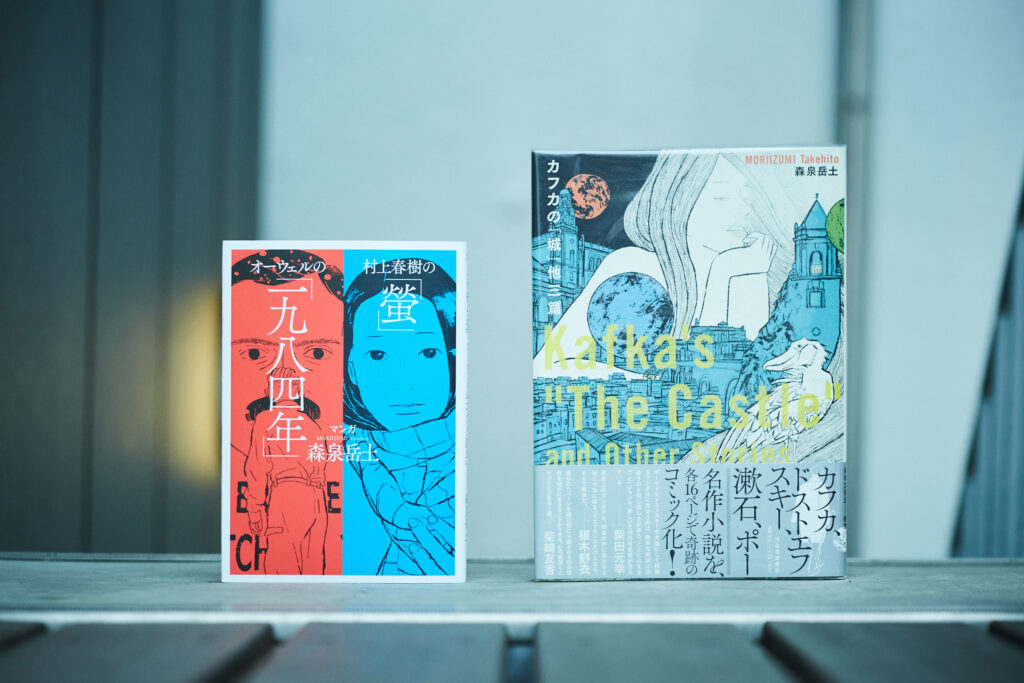

――You’ve also “comicalized” literatures (turn into mangas) in the past, like Kafka’s “The Castle” and Other Stories and Haruki Murakami’s Firefly and George Orwell’s 1984. Why did you select those literatures?

Moriizumi: It’s because they are my favorite literatures. I especially love Franz Kafka’s The Castle. Generally, it is said that the story is absurd, but to me it’s really realistic and funny; I laughed so hard as I read on, but was baffled in the end, as the ending was “incomplete.” It’s even more savage than the way Natsume Souseki often pulls the ladder out from underneath the readers [laughs]. Anyway, I talked to the publisher that it would be a good idea if someone added a story after that “incomplete” ending and turned it into a manga. Then, the publisher told me, “Why don’t you write it?” And I responded without thinking much, “I’m not that into writing a sequel, but I guess I can capture the soul of the work within about 16 pages.” The publisher was interested in my idea, and that’s how I wrote The Castle.

――I was surprised how you managed to incorporate all the intrinsic parts of the long story in 16 pages.

Moriizumi: I have a good reading comprehension [laughs]. The others I “comicalized” like, Edgar Allan Poe’s The Purloined Letter and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Crocodile are also my favorite literatures; Soseki Natsume’s Kocoro was the publisher’s choice. The publisher said to me that, “no one remembers the first chapter of Kocoro, ‘Sensei and I,’” and I thought that’s true as I only remembered ‘Part III: Sensei to Isho (Sensei’s Testament.)’ So, I re-read the novel and thought that I can write it when I realized that the way the character follows Sensei with his eyes at a beach is conveyed exactly like in LuchinoVisconti’s Death in Venice! I went to the beach in Kamakura listening to Gustav Mahler endlessly on repeat. I often go out to places and make a soundtrack that fits the mood of the story to get myself into the zone.

――Is Haruki Murakami’s Firefly a memorable piece to you?

Moriizumi: Actually, other than Soseki Natsume, Ogai Mori, and Yasunari Kawabata, I had never read modern Japanese literature until I got into university. Back then, I casually went to a bookstore thinking that I should probably read some Japanese literatures, and there, I found an array of Haruki Murakami books. I looked for his first ever work, Hear the Wind Sing, bought it and read it, and it gave me a huge impact on me. Since then, I began reading one Murakami book a day. When I was in university, I went backpacking all around the world, and went to Mexico when I was 19 with the book, Norwegian Wood. I started reading when I got to Mexico City, and couldn’t stop as it was so good that even when I was at my next destination, Oaxaca, I didn’t go sightseeing but sat on a bench in a park and read the book for the entire time; I finished the book on the third day of my trip [laughs]. The journey continued, and I traveled to Guatemala from Mexico, and on my way to Tikal ruins, I had turned 20 right when I arrived at this small village called Santa Elena. In Norwegian Wood, there was a moment where the character turned from 19 to 20, and there’s a line that goes, “I felt as if the only thing that made sense was to keep going back and forth between 18 and 19. After 18 would come 19, and after 19, 18, of course.”—I felt exactly that way and thought that I’m walking the same path as the characters in the story.

――That’s quite a formative experience.

Moriizumi: Also, while I was in Santa Elena, the movement of Zapatistas in Chiapas (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) occurred at the border of Mexico and the border between Guatemala had shut down. I was traveling with three other Japanese people, whom I met on the trip, and while we were eating and discussing what we should do, I saw fireflies for the first time in my life—it was also the night I turned 20. I can never forget that view. After experiencing these things on the trip, I read Norwegian Wood and Firefly over and over again, thinking obsessively that they must have been written for me. They were obviously written in a different time period, but I have this profound feeling that I’ve grown up together with these novels. So, Haruki Murakami’s works are really important to me, as they were there with me when I was nobody and helped me grow up when I was 18, 19, and 20. The main characters in Murakami’s novels often get hurt, and even though they are in a situation where they know they will lose, they strive to believe in themselves—they fight for parity and they are individuals who live holding on to their beliefs, sincerely. They were a role model for me growing up.

――And I can tell how special it was to comicalize such memorable novels.

Moriizumi: It was the happiest thing that ever happened in my career as a mangaka. I put in as many ideas as possible in 18 pages. I wish I could go back in time to when I was in college and be like, “you’re going to write a manga of these novels in the future.” I’m sure I wouldn’t be able to believe, though.

When I was comicalizing Firefly, I walked the same route as in the scene where the main character walks from Yotsuya station to Jimbocho, Ochanomizu, Hongo, to Komagome. The views of the surroundings have changed from the time the story was written, however, I thought I’d regret not doing it, so although it was grueling, I took the walk. Even the character, who is a kid in college says, “my body is about to fall apart” from the walk, so I’m proud of myself being a 40-year-old and completing the walk [laughs]. In the story, the characters eat at a soba resultant near Komagome station, so I went there and found probably the same soba restaurant, but unfortunately it was closed.

Whatever I write, it’s going to be Moriizumi’s signature work

――Back when you were a backpacker, what did you want to be when you grew up?

Moriizumi: Well, it’s quite embarrassing, but I thought I would be working normally at a company after graduating university. I couldn’t think of anything else.

――So in other words, you weren’t thinking about becoming a mangaka?

Moriizumi: No, not at all. Or I should say, the idea never crossed my mind. I began working when I was 25, left my parents’ house and started living together with my friend in Nakano. There, I interacted with many people and realized that there are a lot of people living freely in this world. Back then, I was reminded of the time when I was little, I used to go to a drawing studio and loved drawing pictures, and so I started drawing again. It was insanely fun. I then quit my job after working for 10 years, thinking how it would be cool to make a living off of drawing, but of course, in the beginning, I didn’t have any job, so I was drawing mangas for fun and later worked at director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s office for a while. I learned a lot of important things from director Obayashi. Especially what he taught me about the stance and attitude as an expressionist has become my backbone as a creator. I debuted as a mangaka in 2010, so it was 3 years after I quit my first job. I honestly don’t know if 3 years is fast or not. But it’s been 11 years since I became a mangaka and that’s longer than the total years I’d worked as an office worker. It went by so fast.

――Amazing. Is there anything you would like to challenge in the future?

Moriizumi: I want to challenge writing long stories, and there are many more literatures I want to comicalize. In retrospect, I feel like I’ve always been writing stories about “time.” Whether it’s a gothic horror or sci-fi, I’m always writing about “time” that has passed, or “time” that is to come, or “time” that has stopped. Anyway, I want try writing without being limited Whatever I write, whatever the genre is, it’s going to be my signature work. I’m gaining confidence and feeling more liberated as I’m getting older. Even to this day, I wake up thinking, “I’m lucky to be a mangaka.” Like, how lucky am I to be able to draw and do what I like for my job. I’m so grateful. I also praise the fact that I was able to grow up [laughs].

Takehito Moriizumi

A mangaka born in 1975 in Tokyo. He has released various mangas and illustrations rendered with his unique technique of implementing calligraphy ink. The latest manga is Asleep (published by Seidosha.) His works include, Tsumeno Yona Mono Saigo No Ferry Sonota No Tanpen (Something Like a Fingernail and Other Stories) (published by Shogakukan,) Seri, Mukui wa Mukui, Batsu wa Batsu (Part 1 and Part 2) (published by KADOKAWA); he has also turned famous literatures into mangas, such as Haruki Murakami’s Firefly, George Orwell’s 1984, and Franz Kafka’s The Castle (published by Kawade Shobo Shinsha Publishers Inc.)

Twitter:@moriizumii

Photography Kazuo Yoshida

Translation Ai Kaneda