From business to science, the number of situations where people advocate for the necessity of art is dramatically increasing. Although the world doesn’t look different under the influence of the corona pandemic, people’s minds are changing; under such change, how does everyone’s perception of art transform?

Gallerists, artists, and collectors are now researching and trying to predict what kind of art will appear in the post-corona generation.

The ninth installment features Timeline Project. The Timeline Project creates a timeline of female artists who were excluded from mainstream history. Using pre-existing timelines as a template, they created a general history timeline of Western and Japanese feminism and female artists, but the project seeks to add more female artists to it to create a story that highlights individual experiences. The founders started the project to expand viewpoints and vocabulary to create a source that can be discovered from one’s own perspective.

In 2019, artists Yukiko Nagakura and Yasuko Watanabe started the project and hosted the two-day Tokyo Arts and Space (TOKAS) event “Timeline Project WOMEN Artist & History”. Now, anyone can fill out an online form and recommend any artist. The timeline is frequently updated and is expanding everyday.

Nagakura is based in Berlin and works on art that is tied to ecology and gender, while Watanabe works on art based upon finding ways to figure out the boundaries of contact with other worlds and people through travel and maps. I asked the two about their attempt at creating a new way to view art through the Timeline Project.

Making an art history timeline and expanding it publicly

−−I heard the two of you met in November of 2018 through a mutual friend in San Francisco.

Yasuko Watanabe: Yes. I had a chance to do research abroad. I went to the U.S. east coast, U.K., and the U.S. west coast, depending on where I was in my research. During my time overseas, I was able to go to many exhibits that tackled issues around gender and race, which made me realize how much the art scene has evolved and how different it was from the Japanese art world.

Yukiko Nagakura: It had been six years since I had moved to Berlin. It was the year of the 10th Berlin Biennale, which was directed by South African curator and artist Gabi Ngcobo. That particular Biennale had gained buzz because all of the curatorial staff that year was Black. There, I was particularly struck by a Western-style oil painting that featured a Black model. It made me realize that I had only been taught art history through a Western lens. That was the catalyst for me wanting to see art not just from a gender standpoint but from other perspectives. Because a diverse group of people have to coexist in the U.S., living there for a year helped me see that forms of expression are meant to be layered and complex.

Watanabe: I personally had never worked on anything that thematically focused on gender. But when I was a student, I remember thinking there were too many male speakers at an art symposium and wanting there to be more women. When I hit my forties and fifties, I wanted to start a conference where only women could talk about art. There were barely any instances in school where gender was brought up as a theme, and even after graduation, there were cases of harassment at exhibitions because the gender ratio was so unbalanced. I often felt like women were at a disadvantage.

Nagakura: I knew there was a famous gender controversy in Japan from 1997 to 1998, but I felt like the backdrop and significance of it was being lost on the next generation.

In 2012, I moved from Tokyo to a graduate school in Berlin. I remember being shocked that a classmate of mine of a younger generation started talking about white feminism so casually. Because I feel like feminism is derived from wanting basic human rights to survive, I found myself wishing it was a more casually discussed topic in Japan. When Ms. Watanabe told me that there are few places for female artists to be heard compared to male artists in Japan, I thought about what I could do to support those women in Japan from abroad.

Watanabe: I asked Ms. Nagakura what books I should read, and thought I could turn my learning process into a project. I wanted to publicly share what I didn’t know.

Nagakura: Instead of reading books privately, we thought we could make the learning process public, and came up with the Timeline Project. Ms. Watanabe and I were also both separately making timelines at that point.

Photography bozzo, ©Tokyo Arts and Space

Photography Aisuke Kondo

Adding personal perspective to public art history

−−How did you continue to work on the project?

Watanabe: It started when I came back to Japan in March of 2019 because I was selected for the TOKAS OPEN SITE 2019-2020 program’s OPEN SITE dot award. We held the event for two days in December while Ms. Nagakura was temporarily returning to Japan.

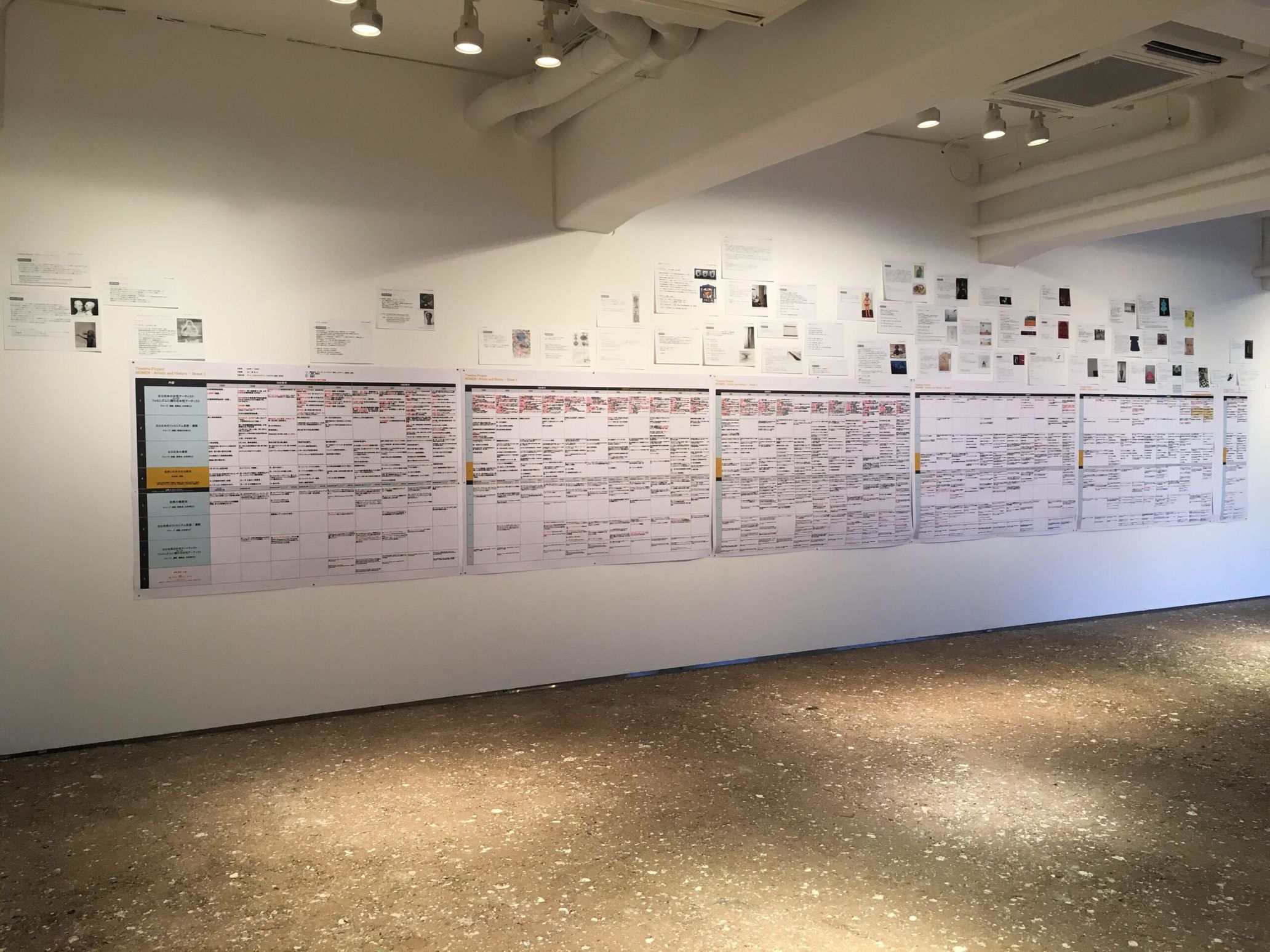

Nagakura: We gathered existing resources about art, feminist art, feminist theory, and world history to archive it as one collective timeline. We also added public recommendations of female artists to be included on the timeline. This way, we could understand female artist history from a diverse and unbiased perspective.

Watanabe: As we were creating the timeline, we realized that there were so many female artists and other minority artists who were excluded from mainstream art history. At the time, we sought out mainstream Japanese books and magazines to reference for our timeline because we thought it would be a more realistic depiction than sourcing from academic books. But even those mainstream resources didn’t mention any female artists. So we quickly changed our approach. We used curator Reiko Kokatsu’s exhibition catalog, technical archives, and other resources for reference to create a more lively timeline that accurately depicts female artist history.

Nagakura: Western feminist art was often introduced in Japan. I also was heavily influenced by foreign artists, which is why I wanted to see a timeline specifically of Japanese female artists. I’m interested to see how Japanese artists have been talked about and how they should be talked about.

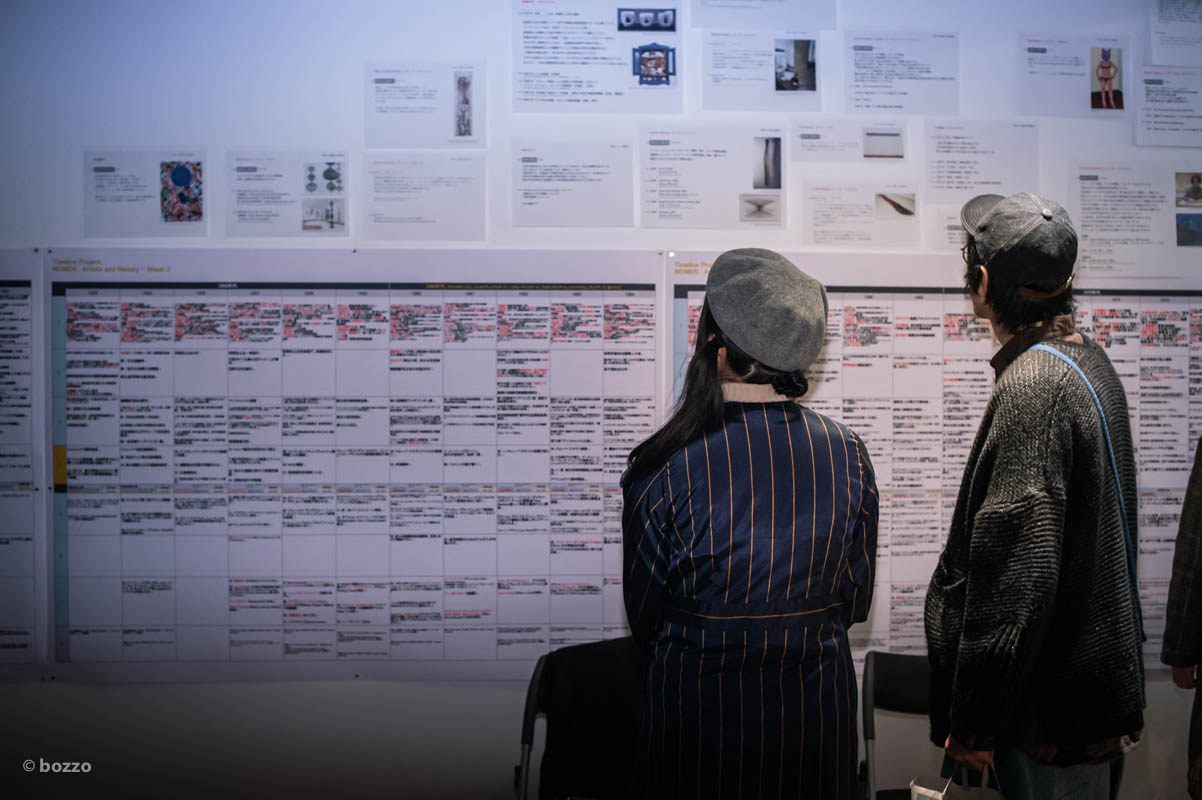

Watanabe: We took public recommendations because we realized we were excluding artists by limiting the general timeline to British and American artists from 1945 to 1999. At the event, we displayed a large timeline on the wall and added the publicly recommended information on top. That started a lot of conversations.

Nagakura: We wanted the public recommendations to tell individual perspectives that would otherwise not be talked about in the “larger story” and democratically add those smaller stories into history. We accept recommendations of any genre, from any era, from any country. We believe that creativity is born out of various mediums, even the picture book you read when you were little. Manga artists and textile artists were also recommended.

Watanabe: Because we’re artists and not researchers, we thought we could accomplish this from a fresh perspective. The actress Emma Watson was also included.

−−Who did you two choose to be on the timeline?

Watanabe: I’ve been influenced a lot by sci-fi, so I wanted to start off with James Tiptree Jr. as a representative. She’s an American writer who went by a pseudonym to get by in the male-dominated sci-fi genre. Before she publicly announced that she was a woman, she made everyone admit that “only James could write these novels” and completely reversed the narrative (laughs). I also included Tales of Earthsea novelist Ursula K. Le Guin. I was heavily influenced by both of their stories.

Nagakura: I chose the printmaker Mayumi Oda. She protested against the Japanese import of plutonium in 1992 and started the org Plutonium Free Future in California and Tokyo, and became an environmental activist. Now, she lives in Hawaii and lives a self-sustaining lifestyle while continuing her work. I also included land art works artist Anges Denes.

−−It must have been fun discovering new people.

Nagakura: There are a lot of people who cross different boundaries and who have various titles and expertise overseas, and that’s expected there. It’s common to have scientists and artists collaborate, because environmental activism and art are closely tied. Environmental issues are tied to the fabric of society. I want this timeline to be a way for people to see the big picture and want to casually learn about different fields of art.

An alternative to big data’s telling of history, the Timeline Project acts as a hub

−−There was a talk at the TOKAS event, too.

Watanabe: On the first day, we had Tomoko Kira, who specializes in contemporary Japanese art history and gender history, talk about Japan’s post-war female writers. On the second day, we had five different women’s collectives and Keiko Takeda, who specializes in sociology, as our speakers. We discussed the possibilities of “siblinghood”, a gender-neutral alternative to “sisterhood” that we advocate for as a way to connect.

Nagakura: Recent Japanese women’s collectives focus on subjects like feminism, queer theory, and female artists. While all having their own unique focuses, they’re all loosely connected, so they all work well together. Timeline Project, Back and Forth Collective, and others and Hettie Judah, an art critic based in the UK translated the cultural facility and residencies guideline “How Not To Exclude Artist Parents”. I’m still a part of a project that derived from that guideline and still hear stories from artists that have children.

−−I feel like you’ve shown us various ways to cooperate. Collectives are a place to experiment with ways to stop new competition or hierarchies from arising. Instead, these spaces encourage friendly cooperation.

Watanabe: Keiko Takeda, the representative for EGSA JAPAN, talked about how organizations can operate without having harassment problems. She not only mentioned gender issues, but also what mechanisms work best when people are interacting and cooperating in social spaces.

Nagakura: Indonesian artist collective ruangrupa was chosen as this year’s Documenta 15 (international art exhibition held in Kassel, Germany) directors, making them the first Asian directors of the documenta. Instead of putting the spotlight on star artists or others who have already had exposure, this cemented the art scene’s move into focusing on cooperative work based in public welfare and care. Personally, I think documenta is a place where that era’s freshest ideas are presented. That’s why I knew the possibilities of cooperation in the workspace were gaining traction in the art scene.

Watanabe: I hope that many people get the chance to speak and that there will be more diversity among event coordinators. In the U.K. and the States, there were always women coordinating talks at art and science events. Japanese talks tend to be fixed on agreement. But in the West, I felt that it was never expected for everyone to agree on something because there were people of all different backgrounds and perspectives in attendance. I want there to be more opportunities in Japan to have discussions on the basis that people are different and have differing opinions.

Nagakura: A teacher at my Berlin grad school, who was a female artist, often brought her child to the university and to exhibitions. I couldn’t find any female artist role models in Japan, so seeing her and being surprised at some of the things she was able to accomplish made me want those things to be more commonly accepted in society.

Watanabe: I’ve started to naturally think about how child-rearing artists can continue their careers, and how Ms. Nagakura is creating better environments for those people. Until now, many people pretended everything was fine while they dealt with family issues or nursing their parents and other private matters. Now we can finally talk about the stresses of trying to manage everything.

Nagakura: Artists are normal people, too.

−−Is it crucial to rest if you’re going to continue something long term?

Nagakura: Exactly, don’t over-exert yourself (laughs). What we do will only be helpful if we can sustain it long term. I don’t want it to end as a short-term fad. I want the next generation to succeed the mission, in whatever capacity.

−−It’s common for the art world to stay exclusive despite their plea to “be more accessible”. The inclusivity of the Timeline Project is refreshing in that way.

Watanabe: We want to visualize what already exists. We want to introduce what we think is cool while publicly displaying our learning process. I think our society is so polarized because of big data. The Internet has helped make the world smaller, but in a skewed way. We aim to value physical communication while also understanding the Internet’s power.

−−The existence of hubs and bridges in the Timeline Project feels similar to that in a secondhand bookstore; it exists outside of big data, and you can accidentally find resources outside of what you were in search of. It’s highly possible to find something new, and you don’t know what books customers will bring in to sell. In that exists an exchange between strangers.

Watanabe: Wow, I used to work at a secondhand bookstore (laughs). There was this book sitting in the corner of the store that was one day sold to someone who lived far away. The book was suddenly given a whole new life, and I felt a strange physical connection to it, all of the sudden.I personally view art in a broad way. I felt like being an art writer was the best way to do what I wanted to do in a multifaceted way. Art can prove that alternative, collective, boundary-crossing acts are possible.

−−It’s true that the Timeline Project is very different from big data. What do you aim to accomplish in the future?

Watanabe: You can now download the β version PDF of the larger timeline, and we constantly update the public recommendation database. In the future, I’d like to connect both. If it wasn’t for COVID, we would’ve relied on our artist connections to travel around the world in search of other female artists. We also started a podcast called “Good Night Limpet” last year that streams on the 26th of each month The podcast’s motto is “freely, earnestly, candidly”. We have guests on the show and talk about a wide variety of subjects, but we try to center it around conversations. Many people find the podcast to be a refreshing talk show that deals with gender and feminism.

Nagakura: The podcast is perfect for listening while doing housework, taking care of your kids, or working.

−−Since you’ve been asking for public recommendations, I hope many people participate.

Nagakura: You don’t have to be knowledgeable about art or feminism to participate. We want to get rid of the notion that you can’t say your opinion if you’re not knowledgeable. We would love it if anyone casually participates.

Born in Shizuoka in 1984, Nagakura has been working in and around Berlin, Germany since 2012. She was a part of the Yotsuya Art Studium from 2008 to 2012. Nagakura finished her masters degree in 2017 in fine art and political theory at the department of spatial strategies at the Weißensee School of Art in Berlin. During her postgraduate program, Nagakura took part in an Erasmus exchange program where she studied photography at the Edinburgh College of Art. Research-based media installations and performances based in ecology and gender are Nagakura’s main medium. Her most recent solo exhibit was “Figures” at the ex-embassy at Atelierhaus Australische Botschaft in Berlin, Germany in 2018. Her most recent group exhibit was “Transient Existence” at Art Object Gallery in San Jose, California in 2019. She is also a member of the Education of Gender and Sexuality for Arts Japan (EGSA JAPAN).

yukikonagakura.com/

Born in Chiba in 1981. In 2007, Watanabe completed her masters degree in fine art oil painting at Musashino University Graduate School of Art and Design.

She considers herself an island-born alien and works on art based upon finding ways to figure out the boundaries of contact with other worlds and people through travel and maps. Watanabe’s work uses sensory physical realities as a starting point to freely go between the scales of time, space, and gravity. She often collaborates with stage plays and founded/runs female artist collective Sabbatical Company (2015). In 2017, Watanabe won the 28th Goto Memorial Cultural Award’s new artist award. As a supplementary prize, she went abroad to ten cities around America and the U.K. from March of 2018 to March of 2019 for research. Her most recent solo exhibit was “WOW! Signal” at GALLERY SIDE 2 in Tokyo in 2015. Watanabe plans to showcase her new works this summer. Her most recent group exhibit was “Small Infinity” at MA2Gallery in Tokyo, in 2019.

yasukowatanabe-space.com/

Edit Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)

Translation Mimiko Goldstein