From business to science, the number of situations where people advocate for the necessity of art is dramatically increasing. Although the world doesn’t look different under the influence of the pandemic, people’s minds are changing; under such change, how does everyone’s perception of art transform? Gallerists, artists, and collectors are now researching and trying to predict what kind of art will appear in the post-covid generation.

In the fifth volume of this series, we speak to Shinji Nanzuka, the owner of Nanzuka Underground (Nanzuka), a gallery that opened in Harajuku in June. Since launching his gallery in 2005, Nanzuka has shed light on artists active in various circles, regardless of trends, such as Keiichi Tanaami. His recent endeavors include the collaboration between Dior and Hajime Sorayama, Daniel Arsham and Pokémon, and 2G, which opened in Shibuya Parco in 2019. He has continued to tear down the walls between fine art and commercial art and has sought new interpretations.

What were Nanzuka’s intentions when he opened his gallery, and how did he grow to the point of worldwide recognition? How does he view the potential of the Japanese art scene in a post-covid landscape?

The meaning behind Underground

——You founded Nanzuka Underground in 2005 in Shibuya, which moved to Shirokane in 2009, and back to Shibuya in 2012 under the name Nanzuka. You then moved the gallery to Harajuku and reverted the name to Nanzuka Underground. Why is that?

Shinji Nanzuka: Initially, Mizuki Takahashi-san, an alumnus of my university and the chief director of MILL6 in Hong Kong, named it Underground. She picked it because the gallery I was trying to open wasn’t mainstream; [she said] I should call the program itself underground.

As an artist, master Keiichi Tanaami has been the backbone of the gallery since the beginning. Society, though, viewed him strictly as a graphic designer, not an artist. However, in 2011, he had a solo exhibition at Art Basel in Switzerland, and after that, MOMA bought his works. Soon, museums were inviting him to show his work. As Tanaami’s prominence rose in the international art scene, I felt like continuing to call the gallery Underground was a disadvantage for him. Also, I felt like it was just a long name for a gallery (laughs).

2G launched in Parco, and the gallery moved above ground, so I changed the name back ironically. Another indirect aim is to make people ponder on the word underground. Just like you did upon asking your question.

——You can’t talk about Nanzuka without talking about Keiichi Tanaami-san. How did you approach the artist, who at that point didn’t have gallery representation and wasn’t known for selling artworks?

Nanzuka: In the early 2000s, Tanaami-san had a solo exhibition at Gallery 360°, and people like Naohiro Ukawa-san and Yamataka Eye-san from Boredoms started the first movement of reappraising his artworks. And I followed in their footsteps. I owe it to Ukawa-san more than anyone, as he’s the reason I earned Tanaami-san’s trust.

The importance of Keiichi Tanaami lies in how his work—which includes different contradictions like political complexes towards America in post-war Japan and cultural love and hate—has contexts and values that should be discussed in terms of contemporary art, not graphic design. I thought that as long as people discovered the story (context), without being swayed by his career or title, the western art scene would recognize him. I had faith that his historical background and uniqueness would play a crucial role when we look back on 20th-century history.

——He’s an artist whose work is received differently in Japan and abroad.

Nanzuka: Yes. Because he experienced the war as a child, his views on Japan-U.S. relations are fundamentally different from those who benefitted from the rapid economic growth as they grew up in Japan after the war. But that’s why he understands the value of freedom of thought, fairness, and equality—the foundation of democracy—more than anyone. Tanaami-san also thinks we should learn about and nurture countercultures like punk, hip hop, and hippie culture. That context directly links to his acclaim today. What’s essential is to explain Tanaami-san’s story based on the rules of art history.

The value of art is contingent on the viewer’s consciousness

——I heard you had a proper education in art history and that your dissertation was on outsider art.

Nanzuka: It was more so about art outside of academism rather than outsider art. When you trace back to when our ancestors used to draw their lives in caves as hunter-gatherers, art history becomes irrelevant. I think things like impulsivity and necessity were rather vital then. My fundamental position is using that as a starting point to re-interpret human expression against the type of art that has become institutionalized as a modern discipline. This is why I became interested in self-taught artists, art created by children, and outsider art. Further, this approach is closer to social anthropology; how do we, as viewers, perceive art and expression in the society we live in now?

I started the gallery not because I wanted to study the past a la artists who had passed away 50 years ago or artists who had been born 100 years ago, which is the basics of art history, but because I wanted to work with people who are alive. We should be skeptical of the monetization of artworks and acknowledge the systemic weakness of how art history only regards dead artists as subjects for research. Takashi Murakami is also systemically fighting against Japan’s conservative art industry, which exists in a fast-paced information society.

——Until Nanzuka was selected to partake in Art Basel, some thought your program wasn’t art.

Nanzuka: The truth is that anti-attitude still exists right now (laughs). I was surprised when we got accepted to show at Art Basel in 2011. However, I had faith that Keiichi Tanaami was going to get international praise, eventually. We were at Frieze London the year before in 2010, and during the screening process, curator Cecilia Alemani came to the gallery incognito to check out Tanaami’s solo exhibition. Perhaps her stamp of approval played an imperative role in putting Nanzuka on the map. In Europe at the time, there already were curators who specialized in lowbrow art and counterculture; this made me understand their open-mindedness towards art. With that said, Art Basel Hong Kong in 2015 and Art Basel Miami in 2018 turned our applications down because of Hajime Sorayama’s artworks. Just like the name Underground suggests, we’ve had our battles (laughs).

——As a gallery in the primary art market, you’ve placed different artists and artworks in fields like fashion and anime, which aren’t seen as art, onto the art scene. Do you feel like you began connecting art and other cultures as you please naturally?

Nanzuka: I’m clear about that because it’s what the artists want. Tanaami made a statement in 1967: “I want to try various methods without limiting myself to one medium such as art or design.” Pop art, which includes Warhol, obviously, and the trailblazing On Kawara’s paintings, was a reaction against consumer society and its propaganda tactics. It highly influenced society by simplifying and pushing an already simple concept. I learned that as basic knowledge, so I felt like differentiating between commercial art and fine art was nonsense from the start. I, of course, didn’t do it. It’s our trait to work with artists that don’t belong to the mainstream, and my gallery naturally became fleshed out because nonconformists came together.

——Now that art, fashion, music, and street culture all intersect, how do you think the cultivation of contemporary art will change in the future?

Nanzuka: It’s natural to want art with a lot of affinity with street culture when that period is at the peak of street culture. Frankly put, that time has arrived now. By the time I opened Nanzuka Underground in 2005, all the Ura-hara rage had subsided, but the style that came out of 90s Shibuya and Harajuku culture had a massive influence on us as students. Back then, people didn’t recognize art by artists similar to Kaws and Banksy as fine art. Today, such art’s recognition is evident when you see them. This issue has to do with the number of viewers, and right now, it has become mainstream for people to understand the value of such art. That’s all there is to it. Art that goes against street culture, which is at its international height, will unquestionably be made ten years from now. I presume the diversity and counterculture spirit in street culture will fuse with a different context and continue to exist, although the term will probably be diluted.

2.Trimming Acrylic paint, acrylic spray, oil chalk, oil paint on canvas

3.Masato Mori Bronze, acrylic paint by artist hand paint, steel

4.Trimming Bronze, acrylic paint by artist hand paint, steel

5.Untitled Drawing on paper

6.Untitled Drawing on paper

©Masato Mori Courtesy of NANZUKA

Managing artists, consulting, and producing; a supportive system

——Could you talk about galleries in the post-covid primary art market and the direction Nanzuka is heading in?

Nanzuka: I reckon galleries that only sell art pieces will steadily decrease. If they try, popular artists could now sell their work directly through social media. Contrarily, mega galleries open branches worldwide and use their name value and connections to bring of-the-moment artists in. That competition will probably be increasingly turbulent in the future. At Nanzuka, we have put energy into artist management to care for the artists while lowering the priority of selling artworks. We also put effort into supporting the production of artworks. Our position is to let other galleries, who are good at selling art, do that job. Tokyo Pop Underground, a special exhibition I hosted with Jeffrey Deitch, reflects the above strategies.

——Many people acknowledge the validity of online art fairs, but they also don’t want the weight of real-life events to disappear. I assume this is also because online platforms are still developing, but does this stem from their differing roles?

Nanzuka: Exhibitions at online art fairs are only effective if their works have previously been displayed. Art is real and raw, so it grows for the first time when it’s physical. Once the pandemic settles down and traveling abroad becomes possible, I’m sure the priority of appreciating art will be restored.

——Art Basel Hong Kong has switched to online streaming, called Art Basel Live: Hong Kong, this year. What did you think about the event, and what potential do you think it has?

Nanzuka: We have a partner gallery in Hong Kong called AishoNanzuka, so we also had a physical booth at the same time. Honestly, I felt like there was a limit to online communication in terms of depth and speed. On the other hand, I felt reassured when the artists were happy with the physical booth.

The possibilities of the art of tomorrow, brought on by complex manga

——What market do you have your eyes on?

Nanzuka: There’s potential in Asia, as many young players are [in the art market], but many trusted collectors become malicious resellers a few years later. Unlike the western market, I get the impression that there’s no etiquette towards culture. I don’t deny the act of reselling itself. But I feel like the amount of foundational knowledge and common sense regarding what the piece means to the artist and humanity indicates that society’s level of culture. We’re not at that level where we can boast, but I suggest those who come to the gallery specifically to resell artworks to try other endeavors.

Skilled collectors collect art to show them to as many people as possible, like Taguchi Art Collection and Takahashi Collection, who have the spirit of taking care of the artworks. Of course, this is made possible by having a budget, but frankly speaking, the best pieces go to those kinds of places. Collectors of this type are rapidly increasing in China. I hope we’ll see more collectors like that in Japan, including the support from institutions. Public museums in Japan have no budget to collect artwork, at any rate.

——Is the education collectors receive essential?

Nanzuka: Yes. The Japanese art market reached negative, not even zero when the economic bubble burst in 1990. The word akutoku gasho (corrupt art dealer) stems from Japan’s incomplete understanding of the art market, which had art dealers that didn’t bear the responsibility of the artwork’s authenticity or art circles that had existed to preserve the integration of the benefit society-like market into department stores. However, the market of contemporary art is global and open, so if people would study a bit more, they’d understand that it’s transparent to the degree that you can see what’s fair and not. Further, the artist’s statement or those who work for a gallery verifies virtually all artworks’ authenticity. Knowing the difference [between fake art and authentic art] is the first step towards becoming a collector in Japan.

Also, many rising collectors buy the works of famous artists at auctions, but art by popular artists is always going to be expensive. If you could prove yourself as a good collector, then you’d be able to buy artworks from a gallery in the primary art market. That’s the fastest route. Now, how can you get your foot into the gallery’s proverbial door?

Recently, I’ve become interested in Toshio Okada-san’s “evaluation economic society,” and have been studying how it’s applied. You can’t quantify the evaluation of people, but to explain a bit about the hidden conditions of selling art, galleries always have a system in sales where they could hand excellent pieces to particular customers. Meaning, said customers’ evaluation of artworks grants them the right to access artworks. What is the criterion for this evaluation? It’s simply about whether their art goes to someone they’re happy with. No artist doesn’t want well-known museums like MOMA in New York to collect their art. Even if it’s not a museum, if it’s a collector that loves the artist’s work like they were family, then they could hand over their art with no worries. If you could see through this insular distribution system—from the perspective of the artist who creates art, rather than viewing artworks as objects—then you’ll understand.

In the sense that you can’t easily explain the value of art and quantify it, I believe art is a unique thing. Recognizing the value of an original art piece, the only one in the world, ultimately relates to why humans exist, no? The fact that the value of artworks didn’t go down during covid is certainly not unrelated to the hypothesis that culture serves as the foundation for humanity’s raison d’être.

——Right before culture hit a turning point, historical famines and global disasters were happening everywhere. Which city are you interested in, now that we’re in a similar situation?

Nanzuka: Even before covid, lowbrow, anti-art was celebrated again as a reaction against the emergence of conservative, exclusionary leaders, starting with America. Artists like Peter Saul, who had an exhibition at Nanzuka in 2019, are at the forefront of this kind of art. Moreover, the appraisal of Black and women artists has been going up.

At Art Basel Hong Kong, we showed the works of Wahab Saheed, a 20-something-year-old Nigerian artist. I think he’ll become an artist representative of young Africans, who pay attention to trends in fashion and music but sustain their sensibilities. You could discern the influence of German expressionists in the early 20th century, such as (Ernst Ludwig) Kirchner, in the composition of his portraits. Much like the birth of sapeurs in Congo, many young people in Africa cultivate their distinct style by reworking European culture. I’m interested in this movement, which sprung from fashion, and how it’s spreading to culture and influencing art.

As you can tell, there’s a new tide in the world, rather than in just one city, but to be specific, the potential of New York and Los Angeles and such is significant.

——Last, what potential does the Japanese art scene have? Could you also talk about the challenges?

Nanzuka: I feel like many of the Japanese manga I read recently have complex compositions. Perhaps this is because more young manga artists can delve into their inner life or culture at large from a global perspective, contextualize that, and translate it into expression. Unlike the sci-fi series, Fist of the North Star, there’s no way Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba could’ve been this popular across all ages and genders when I was a child; it’s heavy, as it reflects a particular historical fact and has brutal portrayals. It would’ve had to be geared towards children and simplified overall. But now, like Attack on Titan, everyone from elementary school children to adults is obsessed with works that have historical teachings.

I have a hunch that there will be many manga books with a strong story, complex structure, and extensive context in Japan. It’d be interesting if a new form of art that applies the grammar of manga were to be born. No artist has written a full-length manga book and then condensed that into one artwork yet.

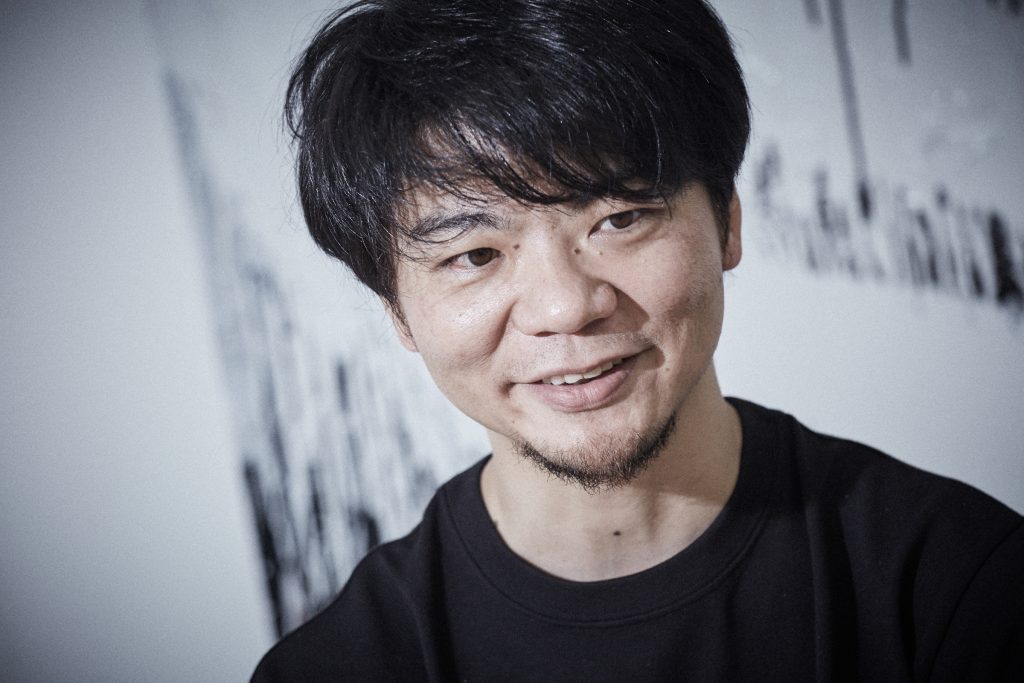

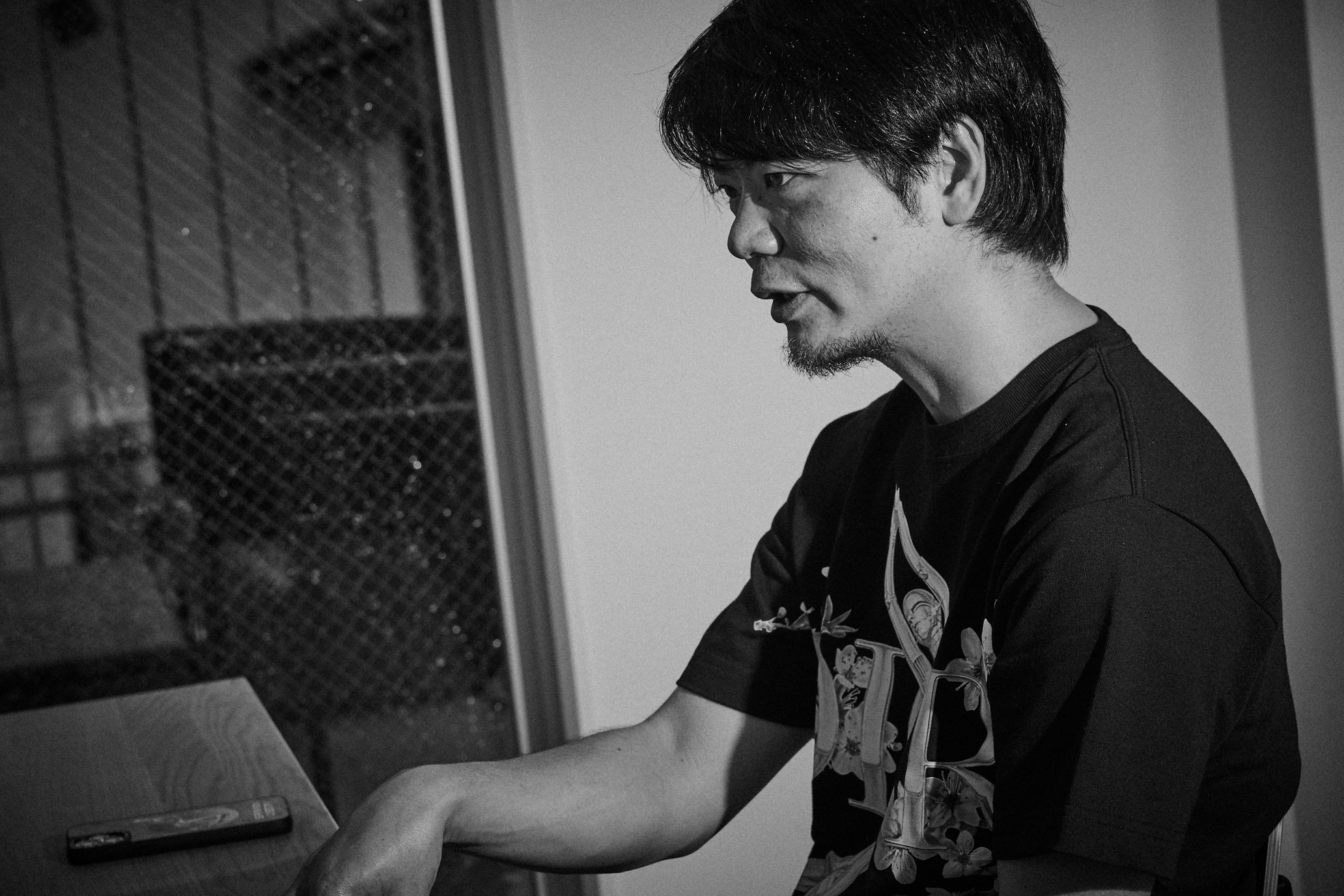

Shinji Nanzuka

Born in 1978 in Tokyo. In 2005, Shinji Nanzuka founded Nanzuka Underground, a contemporary art gallery, in Shibuya. Starting with Keiichi Tanaami, he has revalued Japanese artists outside of fine art like Hajime Sorayama, Harumi Yamaguchi, and Toshio Saeki and expands the horizons of contemporary art. He opened 2G, a shop centered on fashion, in Shibuya Parco in 2019. He then opened Nanzuka Underground in Harajuku in June 2021 and continues his experimental journey of contemporary art and pertinent cultures.

Photography by Kazuo Yoshida