A large graphic art mural — It’s not a matter of whether it’s legal or illegal, but it’s merely an enormous presence exuding discomfort in a pleasant way. It’s a remarkable presence. This graphic art phenomena didn’t start from Banksy. But he may have influenced the people who were only interested in restraining graffitis to shift their interests to something else.

From a long, long time ago, in our towns and society, people have been drawing pictures and leaving their art behind in public spaces. Many people interact with art and learn about the world through art. Today, we are not putting a spotlight on the art we enjoy from below, but we are putting a spotlight on the art we enjoy from above. Furthermore, this article is about a story of the people who draw and leave the art in the playground to jazz up the space.

Spray painting over someone’s tag on the wall is called “going over,” which is ultimately an offensive thing to do. But, then, what do you call when people are frolicking on an art-drawn playground, ruining the art, or a scene of children and people playing around and having fun on an incredibly beautiful art?

Today, I’d like to introduce you to a project where artists and the playground-players collaborate in rendering a large art piece together. It’s a project where the artists paint art on a large canvas of a run-down basketball court. The project is called the Renovation Art Court Project. And this is an article about the organization, go parkey.

In countries abroad, outdoor basketball courts are utilized for various events, including pro basketball tournaments

――First, can you tell us about yourself? You used to be a basketball player, right?

Susumu Ebihara (AB): That’s right. I started basketball when I was 10 at an outdoor basketball court, and I still play to this day. There wasn’t a local Junior basketball team, so I went to the park with my friends whenever we could. It was fun playing basketball freely. We would gather at the school playground on weekdays before morning assembly and after school. On weekends, I would put the ball in my bike basket, bike to outdoor basketball courts in various parks and towns, and have fun playing with older kids and adults.

――I don’t mean to sound ignorant, but do you have a so-called glorious basketball career?

AB: No, I don’t. I never had a chance to join a school basketball team or get into a school on a sports referral. Basketball courts in parks were my place to be, but I could never write down basketball in my resume as a significant part of my career. But I was chosen as a candidate for Japan’s national 3×3 team when I got older.

――So what’s “outdoor basketball”? In which category does it belong?

AB: I don’t think everything needs to be put in a category, but to identify outdoor basketball, it’s a basketball court in parks with hoops and lines that make the court. Typically in Japan, a basketball court is just a part of the public sports facility, but in countries abroad, various events take place at outdoor courts, even high-level tournaments with pro basketball players. It’s also utilized in an eclectic way: for example, for a person to practice shooting or play a 3×3 using the whole court, and it’s not always played traditionally, but that’s what makes outdoor basketball fascinating. Recently, this game that originated from outdoor basketball, 3×3 (three-ex-three or three-on-three), has been approved and recognized as an official game.

――Also, 3×3 was added to the Tokyo Olympic Games, and I heard you were part of organizing the new programme for the Olympics. So, how were you involved?

AB: I took part in optimizing the debuting game to the Olympics format. I had an experience as a player, and in the international project management team, so I was able to use the skills I acquired from these experiences. Specifically, I was part of organizing the venue and coordinating the game rules and operation plans.

When constructing the rules, I communicated closely with FIBA and the Olympics committee members from all around the world. I also had the chance to design the court and the ball for the event, which was an incredible experience for me. However, there were unprecedented troubles like the Olympics being postponed for a year due to the pandemic, spectators being banned from attending, and Mr.Mori (Former Tokyo Olympics chief Yoshiro Mori) resigning…. Also, I had a heatstroke on-site while the game was going on. It was so overwhelming and something I’d never experienced in my life before.

――Tokyo Olympics took place in hot scorching summer weather in Tokyo during the pandemic. The event was entrenched in a spate of concerning issues. I’m sure there were people around you who were also against the event, but what was your inner dialogue during the time?

AB: It was quite an absurd situation. The sports themselves were no harm, but working under such social circumstances wasn’t easy, and moreover, it didn’t pay enough for the time and effort. Honestly, I wouldn’t have been able to get through if I didn’t have this much love for the sport. Every weekend, Olympic protesters were rallying in front of the office, and every day I would hear rumors that it was going to be canceled. Furthermore, the pay wasn’t good, and many people were quitting.

On the other hand, I was questioning myself every day, “Why do I want to keep going with this job?” But this introspection shed light on some positive aspects. My motive to get through was quite simple; my pure, genuine love for basketball was the drive. I firmly believed that introducing the game I’m enamored of, 3×3 basketball, to the world would have a positive impact on the kids’ future in the long term.

Of course, I couldn’t control things, like the postponement, cancellations, and the pandemic per se, but I worked hard, putting all my strenuous effort and holding myself accountable.

――So it’s all worth it even after the Olympics were over.

AB: Yes. I was able to reconfirm that simply and properly enjoying what you believe and love will give benefits to society.

I want to revamp run-down basketball courts in parks and embellish them with museum-level art to provide a safe and fun space for kids and the neighborhood

――Now I’d like to talk about go parkey. Did you have the idea of the project in mind even before the Olympics?

AB: Yes. I started conceiving the idea in 2018 and launched the project officially in 2019.

――By the way, I don’t want to butcher the name…. How do you pronounce it?

AB: It’s go and par-key! Like, Pah-key!

――It’s a coined name, right? What’s the meaning behind it?

AB: Parkey refers to those people who love outdoor courts so much that they pretty much live there. It’s inspired by the word “Pikey” (which refers to gypsies in Europe. Referenced from the film, Snatch.)

――And what exactly do you do for the project? Do you build tent houses on the side of a basketball court and squat in parks with camping cars like we see in the film?

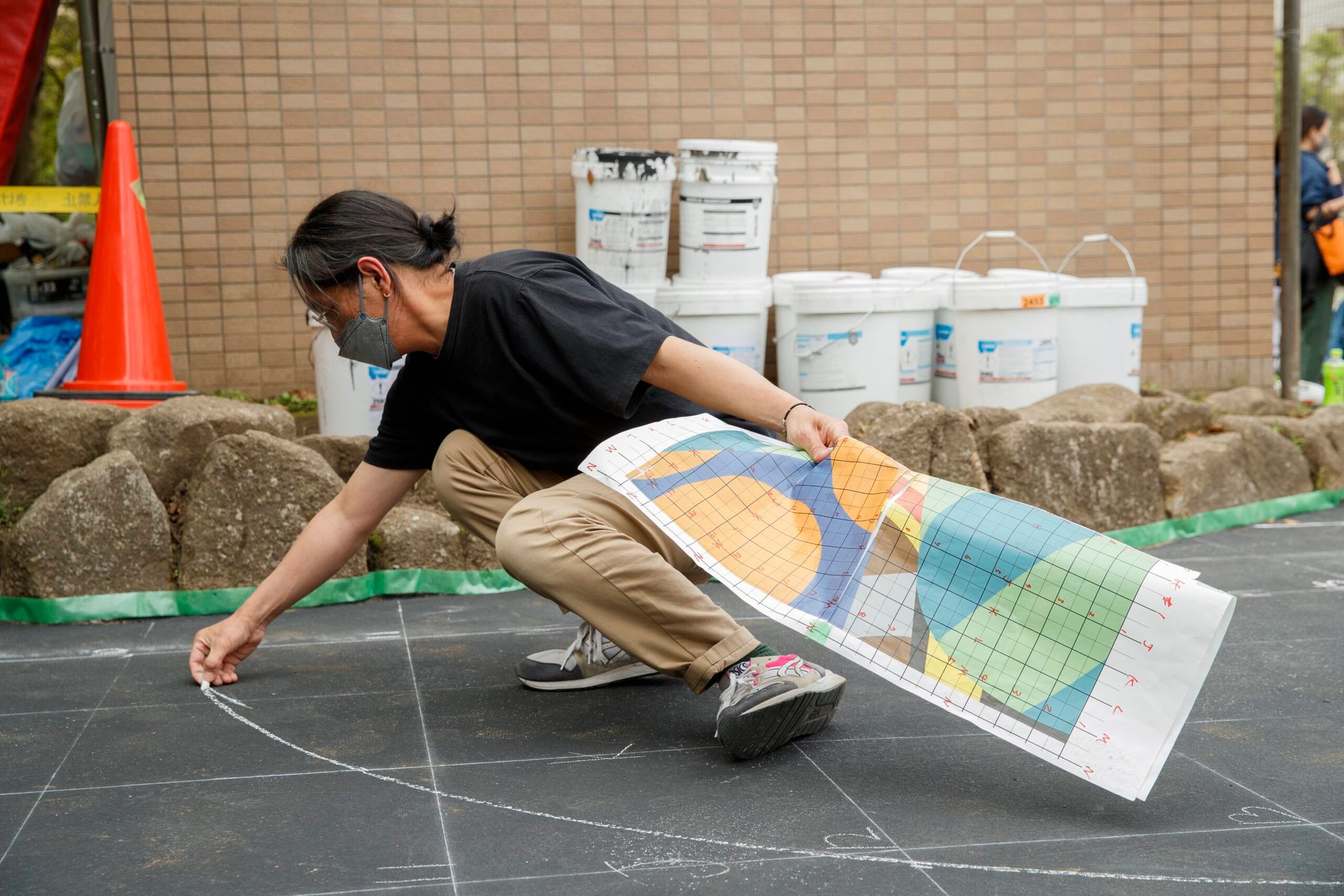

AB: We do nothing illegal [laughs]. Our mission is to renovate run-down outdoor basketball courts and embellish museum-level art to provide safe and fun spaces for the kids and the local neighborhood. We have painters and artists design the court, but the cornerstone of the project is engaging with the community and painting the court together with the kids and the locals.

I believe this engaging experience would encourage the locals to develop a stronger affinity to the space and the neighborhood and help them hone their creativity and inspiration. At least, that’s my confident hope.

――I assume it’s a challenge to explain the project to those who have a penchant for categorizing things — For example, they might ask you if your organization is a volunteer, foundation, or distribution. Perhaps, you might get sarcastic comments saying that this is just another “philanthropic economic activity.”

AB: Maybe I will get some comments like that someday. But I think people could tell that it’s nothing like that as soon as they see the finished art court. People who get it, get it.

――Then, how about this: As long as people can have fun and play basketball safely, they don’t need art on the playground; they may not care at all. I can also imagine the paint fading over time as people play on the court. So I guess my question is, why does it have to be an art court?

AB: Yes, but I see basketball both as a sport and a form of art. It’s a creative sport. For example, you can create a new trick by combining dribbling with a different trick, and players can express their styles with their choice of shoes, accessories, and hairstyles. The art court embodies these artistic factors taken to the extreme.

There’s solid beauty in conventional indoor courts made with simple lines and curves. But, the art court makes the artistic aspect of the sport visible to people, even the players who’ve never been interested in art, and it bestows them with new potential and inspiration.

Another fascinating thing about the art court is that it ages and changes its appearance as the seasons change. I want people to feel the profound energy of the art as they stand and play on the art court.

――Before the interview, you mentioned, “Our project gets mixed up with a beautification campaign or pop-up event.”

AB: I don’t want to be misunderstood, but I think it’s great for outdoor basketball to be hyped up through events. However, in most cases, the courts are only utilized for an event without being featured as the main thing.

Our purpose as go parkey is to do something for the space or contribute directly to the court per se. We don’t want anything temporary; our mission is to leave something in the right way and transform the place into a space where children can explore and broaden their potential.

――I see, so the idea of the art court is to become a platform for new communities and cultures to flourish, spawning bigger potentials. I find this vision is unique to go parkey.

AB: That’s right. Initially, I wasn’t thinking about actively publicizing our project. But now that I see our activity and art court having a positive impact on society, I feel in charge of presenting our project to a wider audience and spreading our messages properly as we leave our achievements.

No license is required to play outdoor basketball, as well as no rules or qualifications required to join

――And your achievements would be the renovated art basketball courts. So, where can we find your achievements?

AB: We opened the first domestic art court at the end of April in Hamamachi park, located in Chuo-ward, Tokyo. We had the painter Shunsuke Imai do the design, and we painted the court together with the local kids. Although it was a new project, we were grateful to have Spalding sponsoring us for the event. Sponsors are crucial for go parkey. Their support becomes the paint, the brush, and the fund for our project. Many corporates are willing to contribute to communities and consumers, but they don’t know how. We are really grateful that Spalding took a bet on us to leave a positive impact on the community, and I hope we have more corporates becoming interested in our project.

――Please tell us more about the artist you curated this time for the project.

AB: Yes, we had the painter Shunsuke Imai. Go parkey is consisted of different opinion leaders specialized in a particular field, and one of our project members living in the US, Dan [Peterson], found the artist. Dan is our respecting partner and the founder of the US-based art court organization — Project Backboard. I remember Dan telling me, “I can feel the right energy exuding from Shunsuke Imai’s works.” Initially, all the members, including I, didn’t know Mr. Imai, but we instantly fell in love with his works. We also thought his art style matches perfectly with the image of the Hamamatsu park. So Dan reached out to Mr. Imai first, then we, the members in Japan, followed with a proper offer.

――So the collaborating artist doesn’t need to be someone from a basketball community? In other words, it could be anyone, and there are no specific qualifications or licenses required?

AB: No qualifications or licenses are required to be our collaborator. It’s the same as not needing any permission to play street basketball. Ultimately, we are looking for art that matches the atmosphere of the playground and sparks our imagination. So, in other words, the artist can be someone from a basketball community if their art matches the vibe of the court.

――Although there are various types of artists, including painters like Mr.Imai and graffiti artists, who exhibit their talent on street walls, I believe most artists prefer doing everything on their own, from drawing the initial sketch to finishing painting the art.

AB: You may be right. But the vital part of our project is, as I mentioned earlier, for the kids and locals to be involved in the project. So it needs to be a painting project in a workshop style, and ultimately, we need to have the actual court users engaging in the painting process.

Also, we want the kids to nurture the connection and affinity with the court through the project. Our vision is clear — the court isn’t the artist’s nor go parkey’s, and it belongs to the community and kids.

Public basketball court is a place for children, the community, and their future

――From a technical point of view, what’s something important other than art and painting per se? Also, what are the challenges you’ve had so far with the project? Are there things you want to improve or ideas you found that may help enhance the project?

AB: One of our challenges was with the rain [laughs]. The rain had circumvented the process of the project more than we’d expected, so we need to figure out a solution. It’s been a battle with the elements. But, like a baller in an outdoor game, we need to perform our best while the sun is out! Do our best as much as we can! These are the common mottos for both outdoor basketball and outdoor painting.

Also, closing the court for a long period of time to complete the painting causes inconvenience to the court users, so keeping up with the tight schedule is another ongoing challenge. Due to certain conditions, we couldn’t do a big event when opening the art court in Hamamatsu park. But in the future, we want to do kick-off events each time we complete and open an art court as a ceremony to infuse life into the space.

――I feel that a project like this needs a compelling story, or else you would have to make compromises all the time. So what would be the important story of this project?

AB: Again, the kids using the court and the locals are always the main subject of the project. go parkey, the artists, and the sponsors should never forget that we are restoring the place for nothing else but them.

――go parkey has just taken its first step of launching the project. I’m looking forward to seeing more projects like this in Japan.

AB: I hope so, too!

――What would be the ideal story to follow for this project?

AB: First, I want people to pay more attention to public parks. I simply think life wouldn’t be exciting enough if there weren’t any cool public parks around. Municipals are struggling with budgets and grasping the citizens’ needs, so we want to support them on that part. Also, I want more people to recognize the beauty of outdoor basketball and art courts. So many stories are spawned from outdoor basketball courts. It’s a space where people have an amazing time playing basketball and making new friends and where culture is born. Finally, I want more people to know that an outdoor park is a dynamic space where you can interact with strangers, be inspired by art, and otherwise.

――As the project goes on, there will be more art courts and playgrounds in Japan where people can enjoy basketball, but it could also be an interactional or educational space for the locals where some can even learn social rules. So, in that sense, your project transforms the place into a jubilant space. But what is something permanent or something that would never change with go parkey?

AB: What never changes is our respect for art, local kids, and the local citizens. As I’ve been saying, the court is a space for the kids, the community, and their future, and it’s not for our complacency and delectation.

――So art, place, kids, and the local communities — That’s all this project needs. Is there anything else imperative for the project?

AB: Our media archive is another crucial part of the project. Go parkey is an art collective in a way. So, it’s vital to keep archives of the finished art courts and record the processes of repairing and painting done by various people working as a whole. I want to keep our project record open for many people to see and know about us. I hope our archives can inspire people.

――Do you have any upcoming plans for the project?

AB: We’re still in our first year as go parkey, but we already have two more projects coming up this year. We are taking our project to other domestic regions next year, as we’re receiving many offers from multiple municipalities. We’re excited to see more unique art courts in different cities. Also, go parkey is all about the love of courts, art, and basketball, and we don’t care about borders. So, we want to travel the world and see different courts and people.

――Finally, tell us your zeal for go parkey. I’m sure you’re very passionate about it, but can you be more specific and describe the passion in words?

AB: There’s a word “lifework,” and go parkey is my lifework. For the rest of my life, I want to produce as many art courts as possible with go parkey. That’s all I’m hoping to do. Wish me good luck!

Susumu Ebihara

Ebihara is the representative of go parkey — the first general incorporation association (unprofitable organization) in Japan, promoting the Renovation Art Court Project. Since his early years, he played basketball at parks and later joined pick-up basketball games and tournaments at public courts abroad. In 2021, he dedicated himself to the Tokyo Olympics as an organizer of the street origin game, 3×3 basketball, debuting in the Olympics, and contributed his experience as a player. Ebihara founded go parkey as his lifework to promote basketball beyond the Tokyo Olympics and its culture to a broader audience. As a disclaimer, “parkey” comes from the word “pikey,” a coined word for ballers or people who are always at the part as they love outdoor basketball so much.

https://www.goparkey.com

Instagram:@go_parkey / @ab_tokyo

Photography Kenji Nakata