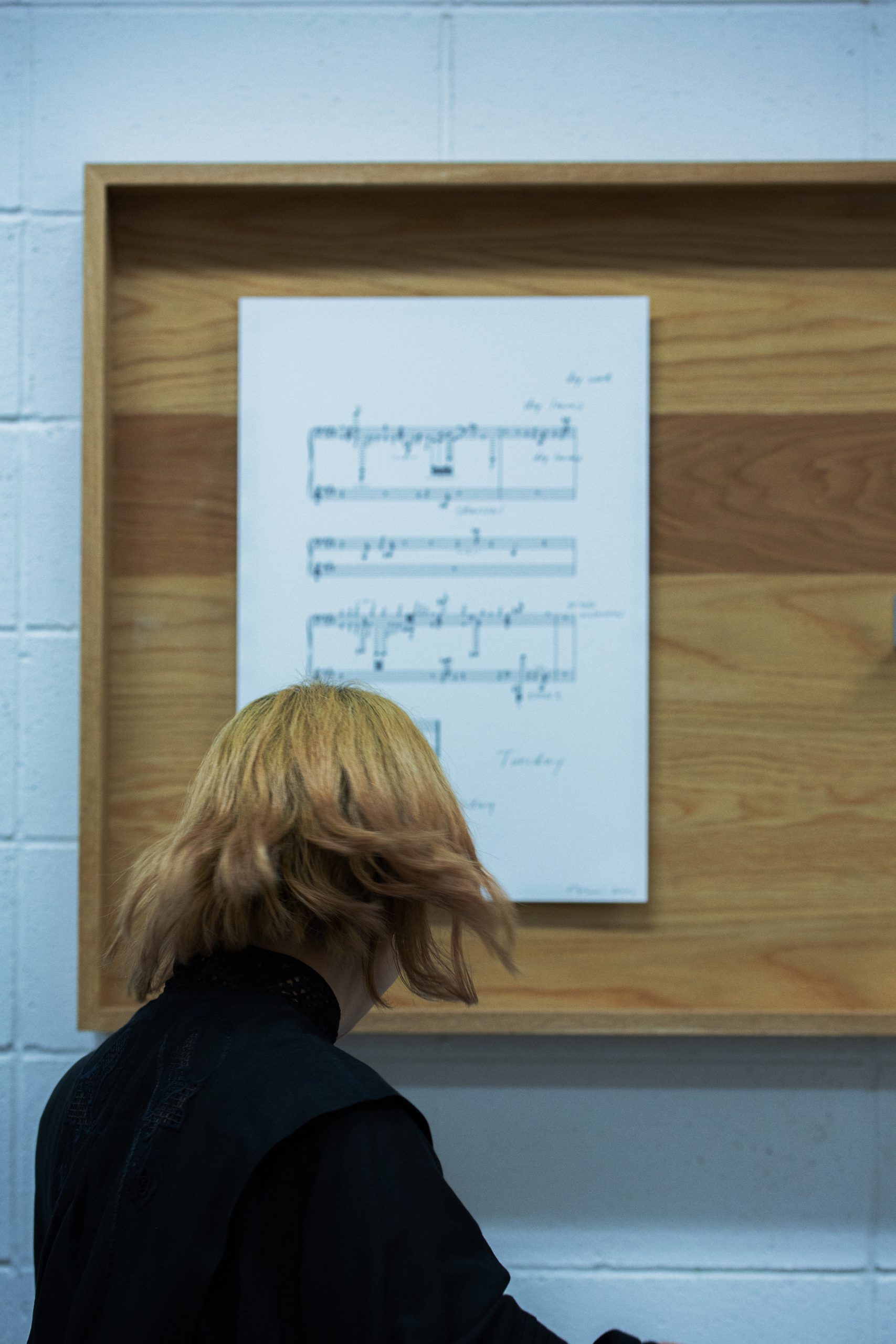

Yuko Mohri, an artist who has made myriad sound-related installations combining everyday objects, junk, and instruments, continues to create new art at breakneck speed since the pandemic hit. In 2021 alone, she participated in over 20 exhibitions, twice the number of shows in previous years. The exhibitions she joined in the first half of 2022 were close to two digits, including Sense Island in Sarushima, an uninhabited island, and the 23rd Sydney Biennale.

What sort of changes has there been in Yuko Mohri’s career post-covid? What interests of hers have remained the same? And what is her perspective on sound? We spoke to the artist, who’s having her first solo shows in Tokyo in over two years: “Moré Moré Tokyo (Leaky Tokyo)” at Akio Nagasawa Gallery from October 28th to December 24th and “Neue Fruchtige Tanzmusik” at Yutaka Kikutake Gallery from November 2nd to December 3rd.

Yuko Mohri

Yuko Mohri is an artist. She approaches installation and sculpture not to compose or construct but to focus on phenomena that constantly change according to different environmental conditions, such as light and temperature. She uses everyday things, junk, and objects found worldwide. Her recent solo exhibitions include “Parade (a Drip, a Drop, the End of the Tale)” (Japan House São Paulo, São Paulo, 2021), “Voluta” (Camden Arts Centre, London, 2018), and “Assume That There Is Friction and Resistance” (Towada Art Center, Aomori, 2018). She has also partaken in many domestic and international group exhibitions, such as the “14th Biennale de Lyon” (Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon, Lyon, 2017), “34th Bienal de São Paulo” (Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, São Paulo, 2021), “23rd Biennale of Sydney” (Sydney, 2022), and more. Her upcoming exhibitions include “Moré Moré Tokyo (Leaky Tokyo)” on October 28th at Akio Nagasawa Gallery and “Neu Fruchtige Tanzmusik” at Yutaka Kikutake Gallery from November 2nd.

https://mohrizm.net/

Overcoming the difficulty of working remotely on exhibitions during covid-19

–You’ve been very active recently. Last year, you participated in more than twice the number of exhibitions in previous years. This year, you exhibited your works in Hong Kong, Sarushima, Sydney, and more. Can you describe your current situation?

Yuko Mohri: These past two years since the pandemic hit have been a clear turning point for me. I used to travel to different places and make art before, but I’ve been creating art at the Toride studio (Tokyo University of the Arts, Toride Campus) these past two years. During the pandemic, I bought a MIDI piano and speakers to do some research and make art in the studio. Before I knew it, I had created a lot of art (laughs). Many projects fell through, as usual, but I still had many opportunities to showcase my work.

Nonetheless, I mostly worked remotely. For my solo shows in places like Taipei, São Paolo, and Oslo, I first rented a space that was as big as the actual venue and made the art piece there. Then, I took it apart, wrote the instructions on how to build it, and shipped it off in boxes. The receiver would watch an instructional video and put it back together like Ikea furniture. I did that over and over. I had always conceptualized my works based on the locations they would be shown in, but since I set my artworks up remotely without actually visiting the physical spaces, the exhibitions felt quite distant. Even when the curator would tell me that my show had been set up, it didn’t click (laughs).

–So you didn’t ever go to the physical venue when you worked remotely.

Mohri: I didn’t. I had a lot of exhibitions, but it didn’t feel like I showcased my work. My participation in Sense Island, an art festival in Sarushima, was confirmed just as I was wondering whether I was okay with [feeling the way I did]. I was at a physical venue for the first time in a long time at Sarushima. My exhibition space was in a long, brick-lined tunnel, so I felt this physical rawness with my skin, like the sound reverberations and cool temperature and humidity while walking. I felt more excited than I thought, making me want to make more art that way.

The mechanism of my piece, I Can’t Hear You, was quite simple: the title came from D.T. Suzuki, whose words I played from two slightly out-of-sync speakers around 100 meters apart. Because of my work schedule, I had to add finishing touches to the piece before the festival started. I listened closely to the sounds and made minor adjustments for two days. I created something I was thrilled with. When I went to the space once the exhibition opened, I saw that the piece next to mine had loud motor sounds, which made me panic. I was like, “No one told me there was going to be another sound piece!” (laughs). It made me realize how unexpected things can happen on-site. It also reaffirmed my desire to make artwork that can communicate something that photos and moving images alone can’t.

Photography Naomi Circus

The rawness of slowly decomposing fruit

–Did you make any other pieces after covid?

Mohri: I made numerous new artworks, one of which is Decomposition, a piece that incorporates fruits. It’s also on the cover of Stone Stone Stone, Yoshihide Otomo’s album, which I made the artwork for. I put electrodes in different fruits so that you can hear the sound of a synthesizer from the speakers. The sound changes according to the shift in resistance value.

Courtesy of the artist, Project Fulfill Art Space, Taipei, Mother’s Tankstation Ltd., Dublin/London and Yutaka Kikutake Gallery, Tokyo

–Why did you use fruits?

Mohri: I participated in a group show in Hong Kong last spring and was supposed to be there first. But I couldn’t go because of covid, meaning I could only work remotely. I enjoy watching energy change in a fluid way or sound and light change depending on the space. When I brainstormed how to express those natural phenomena, I came up with using fruits. I wanted to express the physicality of the venue through fruits because I couldn’t be there in person. I felt it would be interesting because you can get fruits anywhere in the world, and the type of fruits you can get differs depending on the region.

With that said, I didn’t know how my piece turned out because I couldn’t go to the show in Taipei and Hong Kong. Of course, I tested it myself numerous times, but they were just tests at the end of the day. I didn’t know how it changed for a few weeks to months. Amid all that, I showed Decomposition at Yuko Hasegawa’s “Art and New Ecology” show, a commemorative exhibition for her retirement from the Tokyo University of the Arts while I was in Europe during this spring and summer. I finally had the chance to show my work in Japan, but I was abroad, so I had to install the piece remotely (laughs). After I returned to Japan, I went to the venue at the tail end of the show. The heat and humidity of the summer, the smell of rotting fruits, and the psychedelic sound all merged into one, creating an indescribable space. It made me go, “This! This is what I wanted to make!” I’m currently interested in incorporating the things I feel on-site into the narrative of my work, much like the minor adjustments I made to my piece in Sarushima.

Another reason I used fruits is that they’ve traditionally been used as a motif in Western paintings. That’s the art [history] context.

–Do you always go with the same type of fruit?

Mohri: No, I don’t. It’s easy to reference still life in historical paintings and choose fruits that way, but that’s easy. It’s something you see often. I see Decomposition as an open-end sculpture, so it’s not entirely up to me as an artist. I have a rule where the curator or another artist could choose which fruits to use. I witnessed so many fruits I had never seen before for my Taiwan piece. Taiwan is a country full of different fruits; it exceeded my expectations, so that was fun (laughs). Even the sounds were surprising. I didn’t care much about how my artwork smelled at first, but I realized just how important of a factor it was when I saw “Decomposition” at the “Art and New Ecology” show.

Approaching the release of a debut record

–You re-discovered the value of site-specific art once you overcame creating art remotely.

Mohri: Right. I was reminded of something I almost forgot during the pandemic. I was able to feel something, so I want to explore that more. I plan on using big vintage Bozak speakers for Decomposition. Until recently, I used a horn loudspeaker, the type used for school announcements, to create a sound resembling a human voice. Horn loudspeakers were initially made for making announcements, so they capture midranges very well, making any sound appear nostalgic and human-like. I wondered how “Decomposition” would sound with a different type of speaker when I heard it in person. Raspberry Pi, a microcomputer, is what emits the sound, so the audio signals are pretty good. The audio range sounded so beautiful when I tried using the Bozak speakers. My piece transformed into something completely different.

–Why did you buy those speakers?

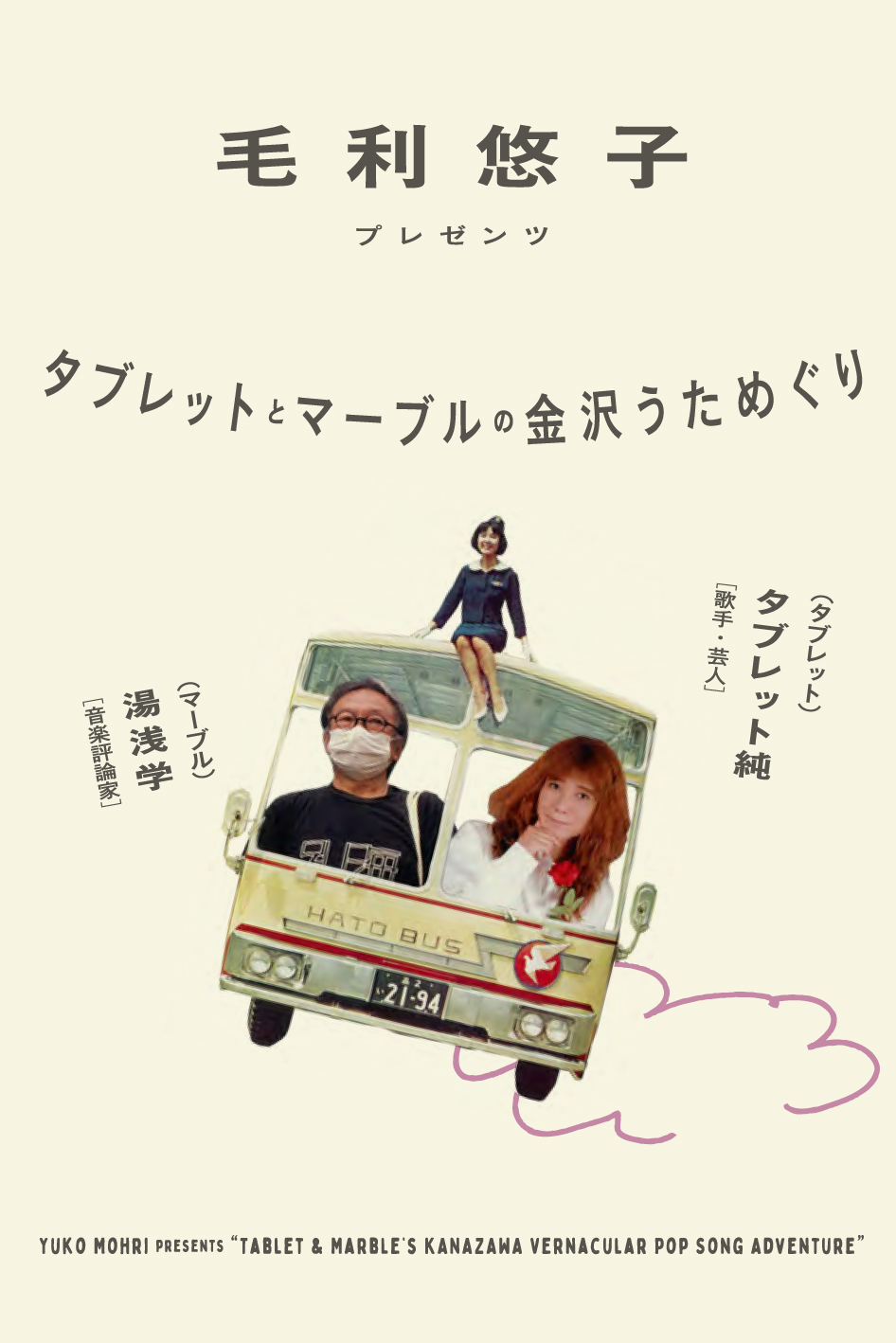

Mohri: Last year, I worked on a new project called Tablet & Marble’s Tokyo Vernacular Pop Song Adventure with Manabu Yuasa and Tablet Jun. The two chatted, played songs with local references like a radio show, and went around the city on a bus. I enjoyed making it. We’re making the Kanazawa version right now, so I’ve been going back and forth with Yuasa. One day, he said, “Yuko, try looking up Bozak on Yahoo! Auctions,” and when I did, a bunch of vintage speakers showed up. He said he wanted to listen to music on Bozak speakers but had no space for them because he already had a lot of big speakers. So I decided to buy them (laughs). Two speakers arrived, so we listened to a vinyl record together. The music sounded so beautiful that I felt moved. I had mostly been listening to music on Bluetooth speakers, so my need for quality sound grew stronger. Before I knew it, I had a collection of Bozak speakers (laughs).

Nowadays, most speakers have one or two cones that play high to low-range sounds all at once, but Bozak speakers have 11 cones, where each unit receives electricity to emit subtle sounds. The speakers can play detailed sound ranges of different instruments because they’re well-suited for orchestras. When I listened to Tatsuro Yamashita’s Softly, I felt like I saw many small faces of his at the beginning of the opening track, Phoenix (laughs). He layers his vocals, right? It was like I “saw” the vocals in an intricate way. I thought it’d be interesting to use them for fruits. I would create sounds using a synthesizer, but I’m toying with the idea of putting vocoder effects on different voices and whatnot. I’m planning on exhibiting this at Yutaka Kikutake Gallery.

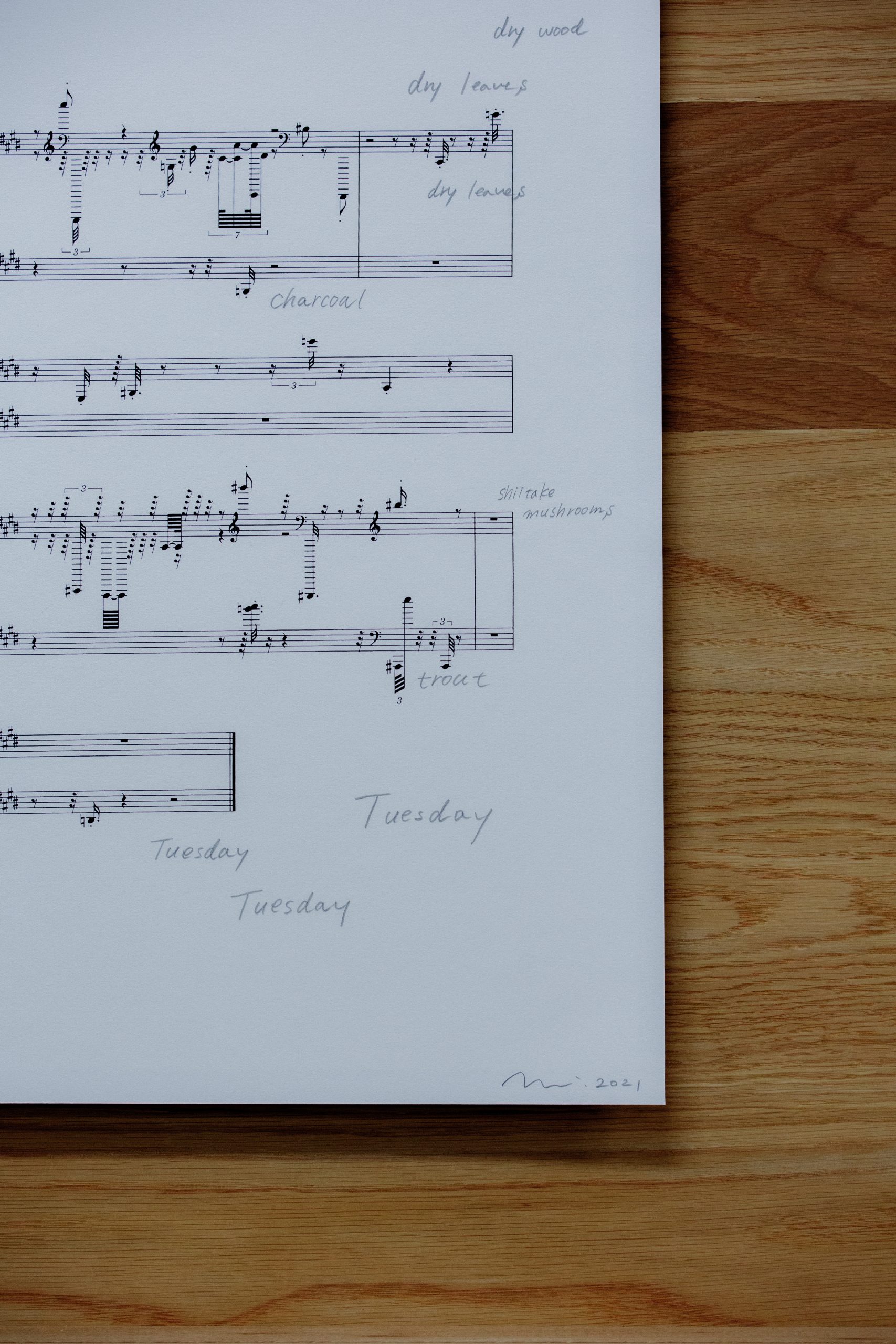

–The show’s title is “Neue Fruchtige Tanzmusik,” right?

Mohri: Yes. The direct translation from German would be “new fruity dance music.” The acronym is NFT (laughs). I went with a German title solely for this pun, but I also think it has an electronic music feel. I’m planning on selling a record at the show. I asked zAk to do the mastering for it. This is my first time releasing one. But I’m not releasing it regularly; I’m thinking of cutting the custom-made records like dubplates and selling them in limited editions. You could hear the fruits in real time at the exhibition, but I plan to document three different audio patterns for the vinyl record. I want to record the changing sounds of rotting fruits accurately. I wouldn’t say this is a return to analog mediums, but records and audio are interesting. Sounds change when you play them on a turntable; they can transform by changing the cables. It’s so fun manipulating sounds on-site.

The authorship of sounds or not composing music

–In terms of the sonic aspect of Decomposition, I’m assuming the focal point is how to convert the data you get from the fruits into sound. Your authorship as the artist would inevitably appear in the sound, right?

Mohri: You’re exactly right. I first converted fruits into sound 15 years ago, when Tetsuya Umeda and friends had a show in Denden Town in Nipponbashi, Osaka (“Denki-hibition” at the Technopolitan Museum, in 2006). A junk shop called Digits specialized in electronic parts and sold different types of electrical resistors. I felt it’d be interesting to sell things like eggplants and cucumbers. Because vegetables contain water, you can measure their resistance value like an electrical resistor. I measured the water volume of the vegetables, marked the resistance value with colored tape, and sold them at the electronic store. That was my exhibition. Eggplants and cucumbers are objects, so you’d think their respective resistance values would remain the same. But when I tried to measure them by sticking electrodes in the vegetables, the water volume changed more than I expected. As a result, the numbers changed too. I was moved by the fact that the outward appearances stayed the same, yet the water volume inside altered. That experience stayed in the back of my mind, so I felt like I could create a piece with frequently changing sounds by converting the resistance value of fruits into sound.

I spoke to a programmer about how I could make it happen, and we went through trial and error and landed on using Sonic Pi, a programming software for Raspberry Pi. I periodically measure the resistance value from fruits and change the pitch using synthesizers. There are various synth tones, so I first used a Casiotone, but it was a typical synthesizer. I’m currently in the middle of testing different methods because I want to focus more on the tone, like figuring out if I can sample my voice or object sounds.

Courtesy of the artist, Project Fulfill Art Space, Taipei, Mother’s Tankstation Ltd., Dublin/London and Yutaka Kikutake Gallery, Tokyo

–Are you trying to listen to the “voices” of vegetables?

Mohri: Perhaps. I’m the type who makes things as they go rather than establishing what to make at the start, so I’m still thinking about what the final concept will look like. I also came up with the title, Decomposition, in the middle of making it. I left Tokyo for a while to live in the countryside during the pandemic. I was composting food, and the title came to me then. Decomposition means disintegration or rotting, while composition could mean songwriting or constructing something. It has the “de” prefix, so you can interpret “decomposition” as the opposite of composing music. Rather than making music, this piece is about the pitch of sounds changing according to the water volume of fruits. That’s why I thought “decomposition” would work perfectly as the title.

It also works as a statement: “I don’t compose music.” The fruits design the sounds on their own. I might come across as an accidental composer, but that’s part of the concept. Pierre Boulez once called John Cage’s music “chance by inadvertence,” and I don’t see inadvertence as bad. The statement, “I don’t compose music,” means I, as the artist, don’t choose the sounds. In Cage-like words, I let the sounds be. Live electronics are at the root of the idea behind Decomposition, after all. But I don’t completely leave things as they are, as I have some principles. I try to see the overall balance, which might be an eternal pursuit for me. I don’t want to make music; it’s about figuring out how far I should go to create optimal sounds if they exist.

Anti-tympanic or movements that shift fluidly

–I feel like your approach could generally be separated into three categories: sounds that intervene in one’s sense of hearing, sounds that are born from accidental movements, and sounds that use music as a motif. Do you ever categorize your work like this when you make sound art?

Mohri: No, I don’t. The thing I’ve always been most interested in is movement. I’m interested in how the cityscape and society change fluidly, and I always think about what I’m looking at and what I can create. It’s more so about movements than sound. I have a big show from next year onwards, and I plan on making “movements” the theme. As you said, sounds are born from movements. But those movements don’t always come from the artwork. The artwork can change according to the viewer’s movements. By walking through the tunnel, the viewer could hear I Can’t Hear You in Sarushima differently. Likewise, I want my next exhibition to be one where the experience is affected by where the viewer stands and how they move rather than a change in the environment. It sounds quite abstract, but I want to make a show where the viewer can look at the ocean while standing or something like that (laughs).

–In the official book for “Assume That There Is Friction and Resistance,” Minoru Hatanaka praised the exhibition, probably with Duchamp’s “anti-retinal” paintings in mind, saying it didn’t limit itself within an audible range and that the thought behind it wasn’t limited to “tympanic” sounds. Dealing with sound as movement could be considered as such a movement.

Mohri: When I listen to sounds, it feels like I’m looking at electricity. To be obsessed with audio is to polish dirty electricity and make it pure. It’s about how you can create clean electricity onto sound by changing cables and sources of electricity. That’s why when I listen to music on Bozak speakers, I can’t help but wonder how electricity is moving inside. With Decomposition, it goes without saying I’m interested in its sound, but I’m more concerned with the movement of electricity deep inside when I’m putting it together. When I used water for Moré Moré (Leaky), a three-dimensional sculpture, the main point was the water movements. Many objects guided the movement of water, but I was interested in the movement of the water itself. You had to consider gravity, and water is a difficult material to control because it’s hard to adjust the water pressure using a pump. The fun part about that sculpture was how you could try to control the water but end up with a shape you didn’t even think about.

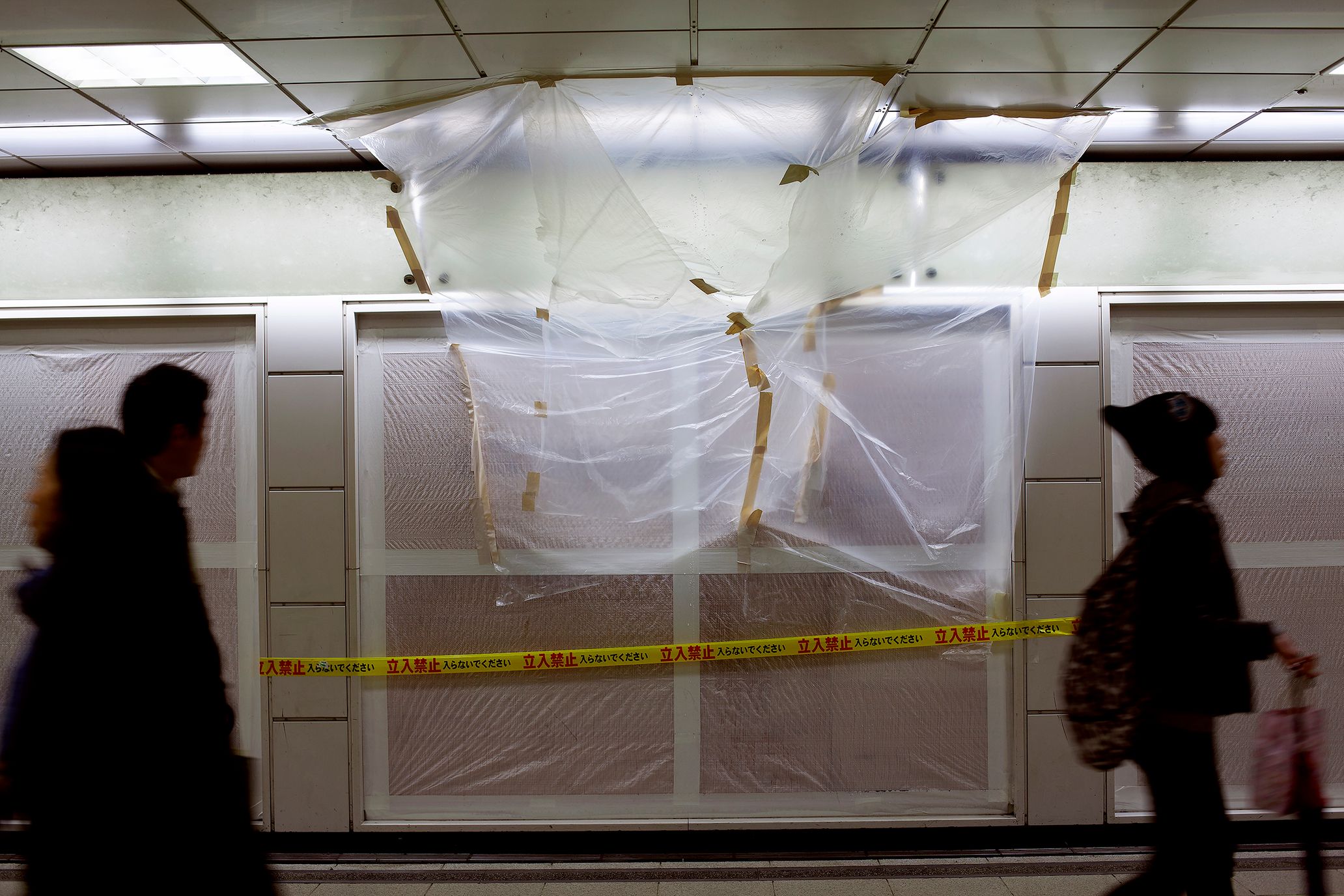

For my exhibition at Akio Nagasawa Gallery, I’m planning on making big prints out of 22 photos taken from Moré Moré Tokyo (Leaky Tokyo). After the Tokyo Olympics ended, I tried observing the streets of Tokyo again. When I walked the streets for the first time in a long time, I saw that the measures to fix water leaks became boring. Ten years ago, train station workers used various objects in unique ways, but now, they connect parachute-shaped transparent vinyl funnels to hoses. That’s become the norm. Efficient methods to stop water leaks feel boring. I felt like it was the end of an era, so I decided to put on a photo exhibition. This isn’t limited to water leaks, though. So many things that were normal ten years ago have changed; for instance, listening to music via Bluetooth is becoming the norm today. That’s why. I’m interested in figuring out how we should deal with those big societal changes.

Courtesy of the artist, Project Fulfill Art Space, Taipei, Mother’s Tankstation Ltd., Dublin/London and Akio Nagasawa Gallery, Tokyo

–What you spoke about just now—Moré Moré Tokyo (Leaky Tokyo)—illustrates how improvisation has become stagnant.

Mohri: Yeah, exactly (laughs)! You’re right. Even with improvised music, when people start trying to show something they’ve mastered each time, it can make you think, “Well, that’s enough of that.” It’s not a bad thing to fix water leaks efficiently. Quite frankly, I felt like it was the end of an era. I thought it was a good time to have an exhibition to mark the end.

Courtesy of the artist

Photography Kuniya Oyamada

Art and politics, or an infinite number of small movements and resistance

—Moré Moré Tokyo (Leaky Tokyo) has a similar aspect to improvised music, which is interesting, and at the same time, it has a political aspect. It suggests the government’s negligent, ad hoc attitude toward infrastructure development. What are your thoughts on the relationship between art and politics?

Mohri: Every time I go to different places abroad, I run into many political environments. For instance, censorship in Hong Kong is ramping up right now, and even with Decomposition, people ask me whether the fruits have a political meaning. In China, I had an exhibition with American artist David Horvitz, and the location in his video was a golf course that Trump goes to often. My video showed the Pacific Ocean at dawn, so it might’ve seemed like I had some message from Japan to America (laughs).

The Global Art Practice Department at the Tokyo University of the Arts, where I started working five years ago, is unique. Over half of the students are from other countries. There are students from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, not just the West. I teach the classes in English. My students often tell me real stories regarding how danger is so close to home. For example, Russia might become omitted from the list of partner countries for scholarships, an ideological decision. There’s nothing wrong with the individual students themselves. In today’s world, we tolerate the idea that we can split deep, complex individuals by enemy or foe and change how we treat them. Everything is complicated, so when we assert one opinion, we inevitably hide the other side’s tragedy without seeing it.

Japan is an isolated country in terms of language, so many things present themselves as one-sided. I can’t entirely agree with the tendency to hastily come up with an answer by thinking of things in terms of extremes because they’re multifaceted. Of course, there is a lot of amazing political art, but I can’t help but think of things from multiple perspectives. I can’t make something that presents an issue in just one way.

I feel like my political statement lies in how I create many small, meticulous resistances, just like what I did with “Assume That There Is Friction and Resistance.” I want to view things in the world by creating many small movements or vibrations and resisting them. It is an abstract expression, so I don’t know when and to whom I’d be able to communicate that.

When I look at paintings from the Russian avant-garde era and Vladimir Tatlin’s sculptures today, a century later, I can feel that they were resisting in subtle ways. It makes me realize that there were people who resisted 100 years ago. The interesting thing about art and music is you can feel something, even if they’re abstract. If I can leave my work behind for posterity, I hope they can feel like, “I didn’t know an era like this existed” by looking at my subtly resistant artworks. People might discover meaning in my work by looking back 100 years ago, as how people view or apply meaning to things can change drastically in just a decade, like in Moré Moré Tokyo (Leaky Tokyo).

■Moré Moré Tokyo (Leaky Tokyo)

Date: October 28~December 24

Venue: AKIO NAGASAWA GALLERY GINZA

Address: Ginsho Bldg. 6F, 4-9-5 Ginza, Chuo-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 11:00-19:00 (closed 13:00-14:00 on Saturdays)

Holidays: Sunday – Monday and national holidays

Admission: Free

Web site: https://www.akionagasawa.com/en/exhibition/more-more-tokyo/

■Neue Fruchtige Tanzmusik

Date: November 2~December 3

Venue: Yutaka Kikutake Gallery

Address: 2F, 6-6-9 Ropoingi, Minato-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 12:00-19:00

Holidays: Sunday – Monday and national holidays

Admission: Free

Web site: https://www.yutakakikutakegallery.com/en/

■21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa Art Bus Tour Tablet & Marble’s Kanazawa Pop Song Adventure Presented by Yuko Mori

Date: November 3

Venue: 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa

Address: 1-2-1 Hirosaka, Kanazawa-shi, Ishikawa, Tokyo

Hours: 10:00~、13:30~(About 2 hours and 15 minutes)

Admission: Varies depending on the program (Kanazawa and Toyama citizens receive free admission to exhibitions hosted by the museum / proof of residence such as a driver’s license is required).

Capacity:20 (prior application priority)

Disc jockey: Jun Tablet (mood singer and comedian), Manabu Yuasa (music critic)

Web site:https://www.kanazawa21.jp/data_list.php?g=69&d=1991

Photography Hiroto Nagasawa

Edit Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)

Translation Lena Grace Suda