Masculinity. It’s a word that doesn’t refer to something tangible, but rather, to our perception of certain characteristics as manly. Our awareness of the concept of masculinity is demonstrated by common phrases like “real men don’t cry” or “man up.” In other words, when we praise or criticize others, we have a tendency to judge whether or not someone is behaving in a way that matches our perception of how their gender should act. Why do we think this way? “Masculinity” stands out in its ability to bring this question to the forefront.

This spring and summer, the Barbican Centre in London, one of the largest cultural facilities in Europe, held “Masculinities: Liberation through Photography.” This large-scale exhibition explored the theme of masculinity, bringing together over 300 works by over 50 international artists, photographers, and filmmakers. Due to the vast nature of the exhibition, I would like to focus on the works that particularly left an impression on me.

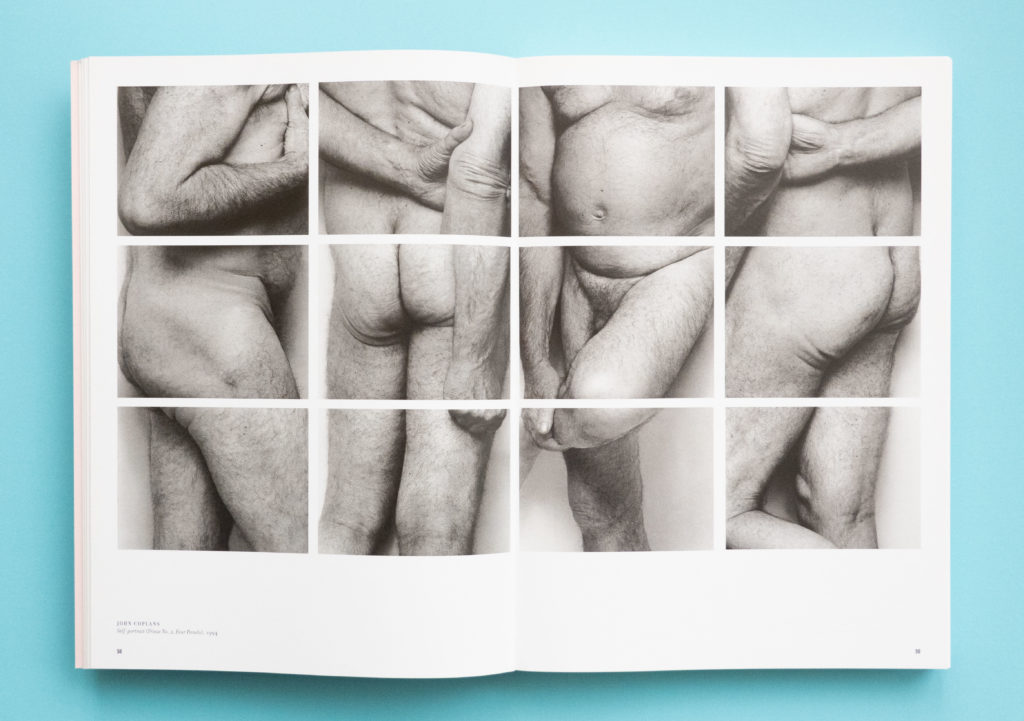

The first section, titled “Disrupting the Archetype,” begins with “Self Portrait,” (1994) a massive piece by John Coplans that exposes his aging, naked body to the camera. Framed from chest to knee so his face is out of the shot, Coplan’s body seems to have been stripped not only of clothes, but also its masculinity through aging, weight gain, and a bit of playful posing. In the figure, one might see the play described in Johan Huizinga’s “Homo Ludens.”

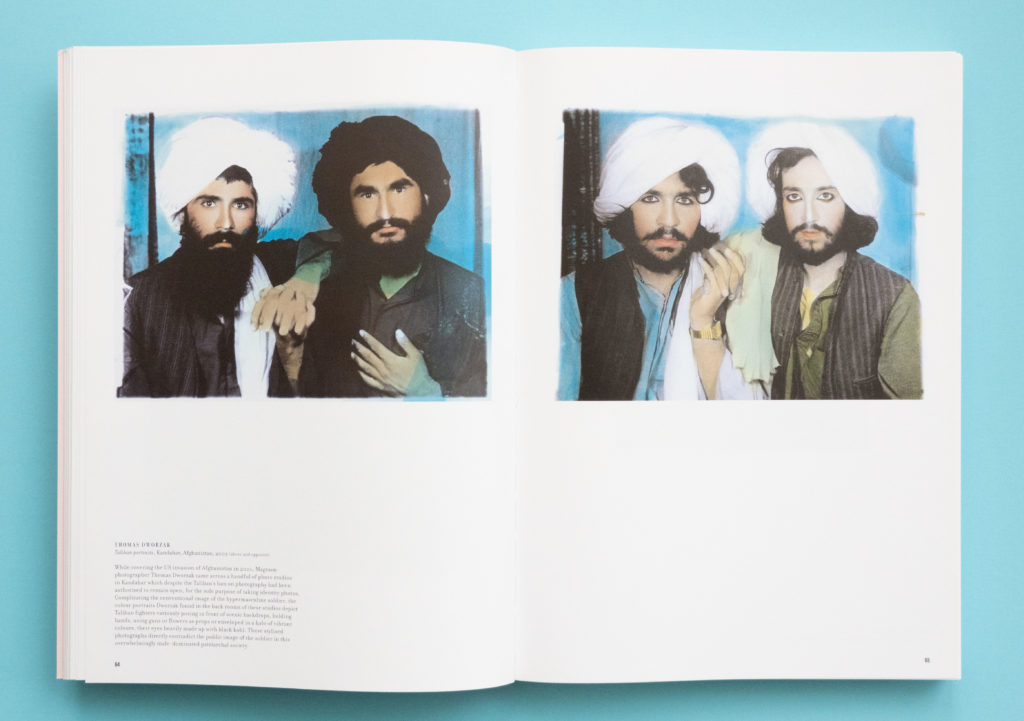

“Taliban Portraits” (2002) is a series of unusual photos found by Thomas Dworzak, a member of Magnum Photos. While covering the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, Dworzak stumbled upon a local photo studio. There, he saw identification photos of two soldiers intimately holding hands. The photos in these series are vibrantly colored, depicting soldiers with cheeks stained red as if wearing makeup, using guns and flowers as props. These photographs seem to directly contradict the conventional image of the hypermasculine soldier in Afghanistan’s rigid patriarchal society.

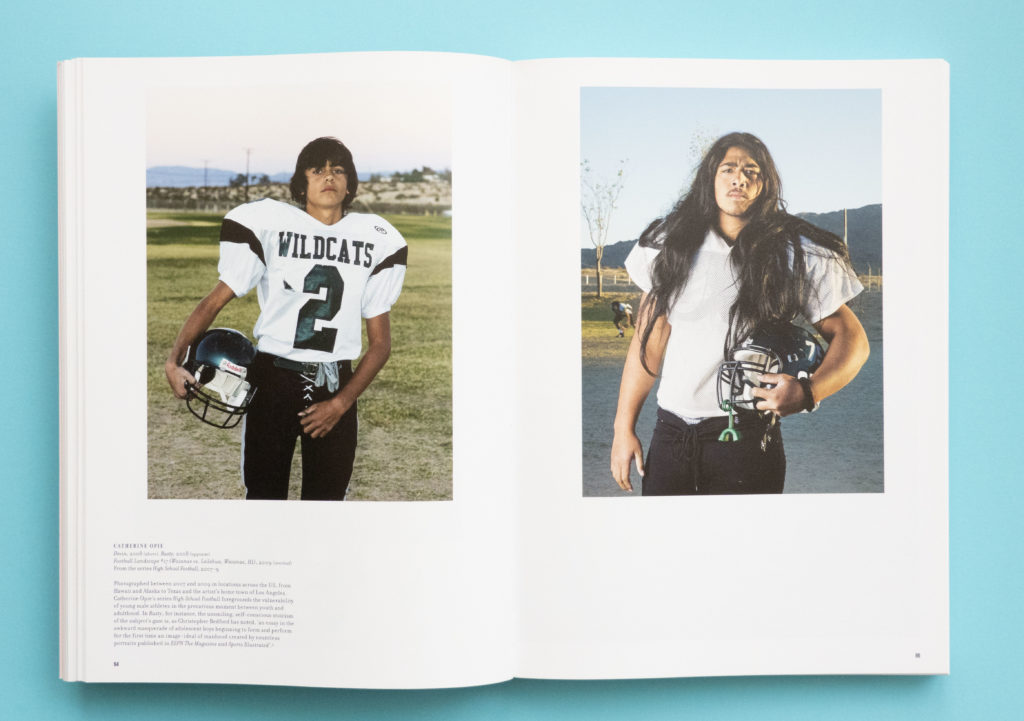

Catherine Opie’s “High School Football” (2007-09) series reveals the surprisingly vulnerable state of young football players. Football is considered to be one of the most popular American sports, but the players depicted are young men who have not yet reached adulthood. They stare at the camera quizzically, in contrast to the stereotype of the strong athlete that we tend to imagine.

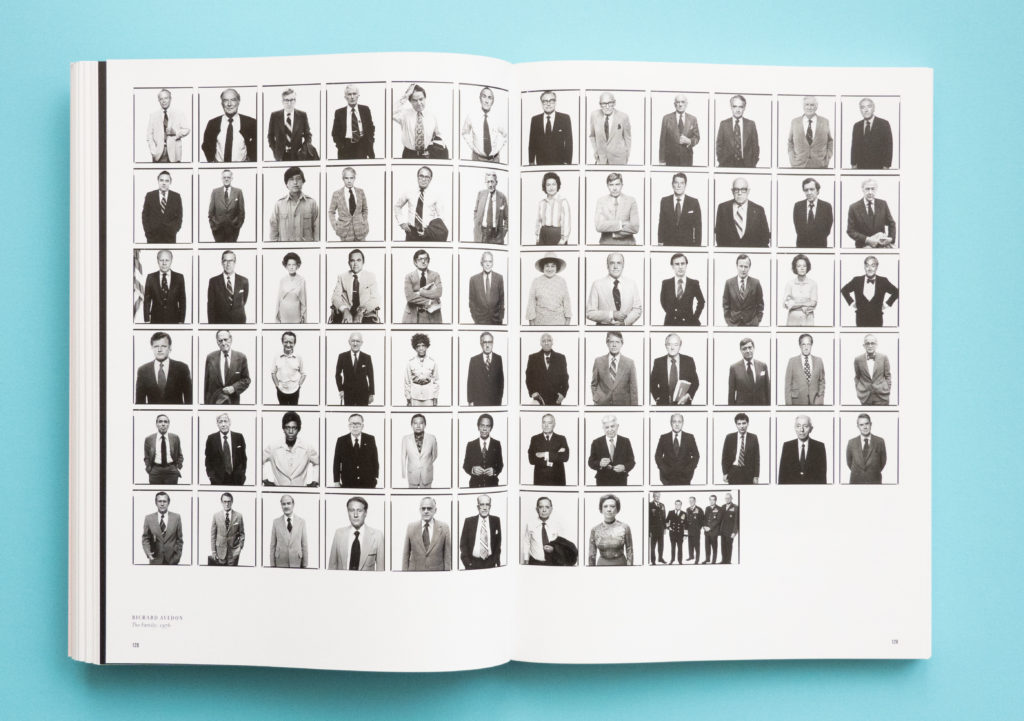

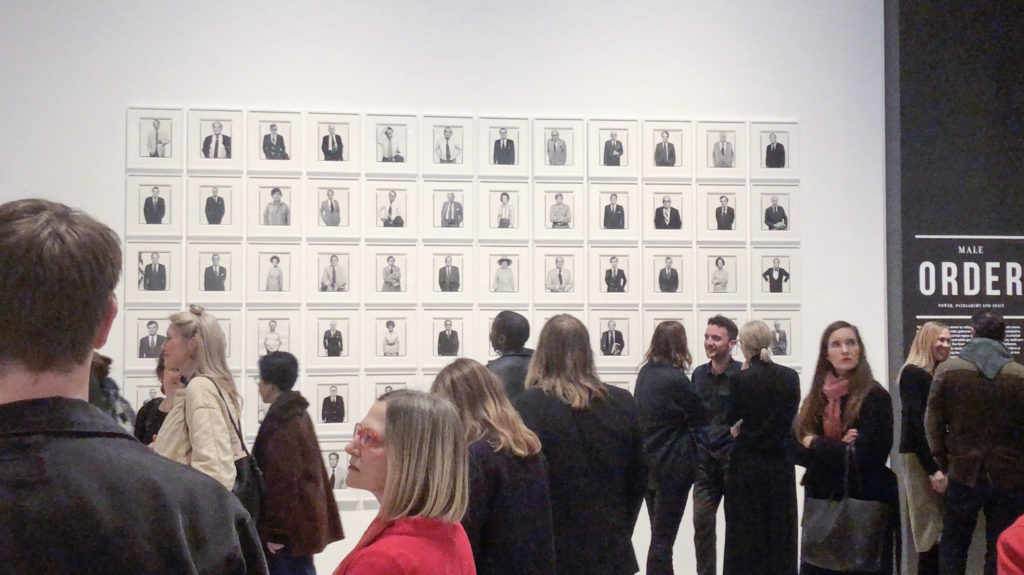

The next section, titled “Male Order: Power, Patriarchy and Space,” brings together works that tell the story of male domination and hegemony. In terms of impact, one of the most memorable works in the exhibition is Richard Avedon’s “The Family” (1976).

In 1976, Avedon was commissioned by Rolling Stone magazine to take photographs in advance of the upcoming U.S. presidential election. The 69 photographs he took show the leaders of American society at the time, with Gerald Ford as the head. While the title conjures up images of the Mafia, bringing these figures together through photographs seems to ironically suggest that they were a “family” on the political stage. Since the subjects include future presidents such as Ronald Reagan, Jimmy Carter, and George Bush, the series can be interpreted as a family album spanning the decades of American politics to follow.

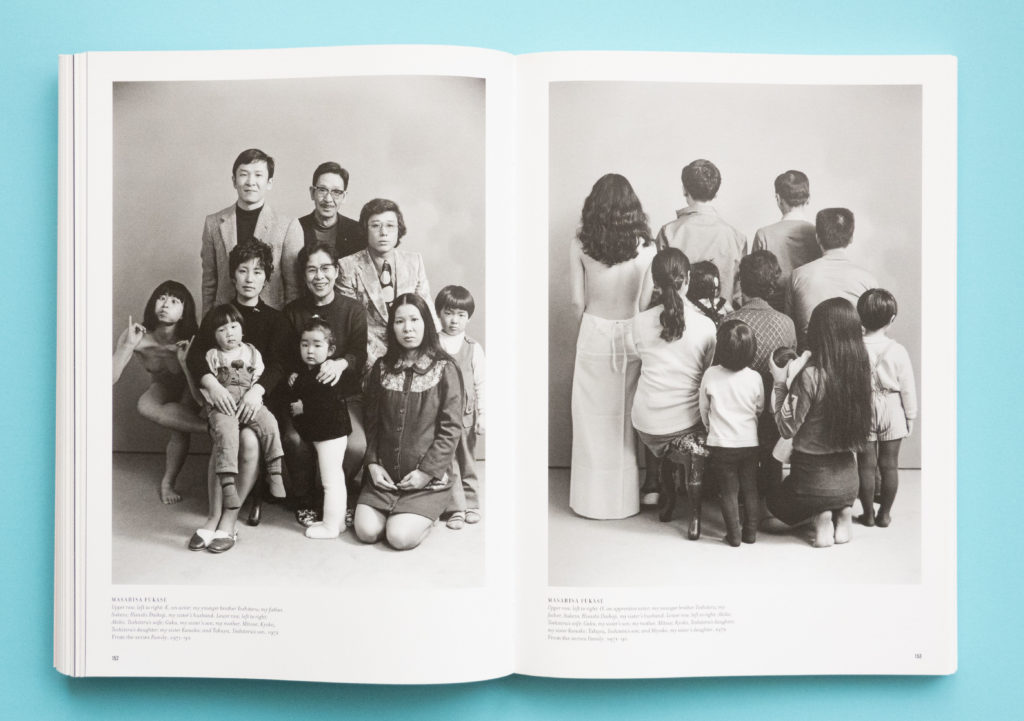

The next section, “Family and Fatherhood,” began with two works, “Memories of Father” (1971-1990) and “Family” (1971-1990), both by the only Asian artist in the entire exhibit, Masahisa Fukase. Both works were documented over a 20-year period and are based on his own family, which was headed by his father, Sukezo. After the death of Sukezo, the family began to fall apart, and eventually both works conclude with the breakup of the family and the closing of the photography studio. The way the death of the patriarch leads directly to the collapse of the family shows the structural problems behind a dictatorial patriarchy.

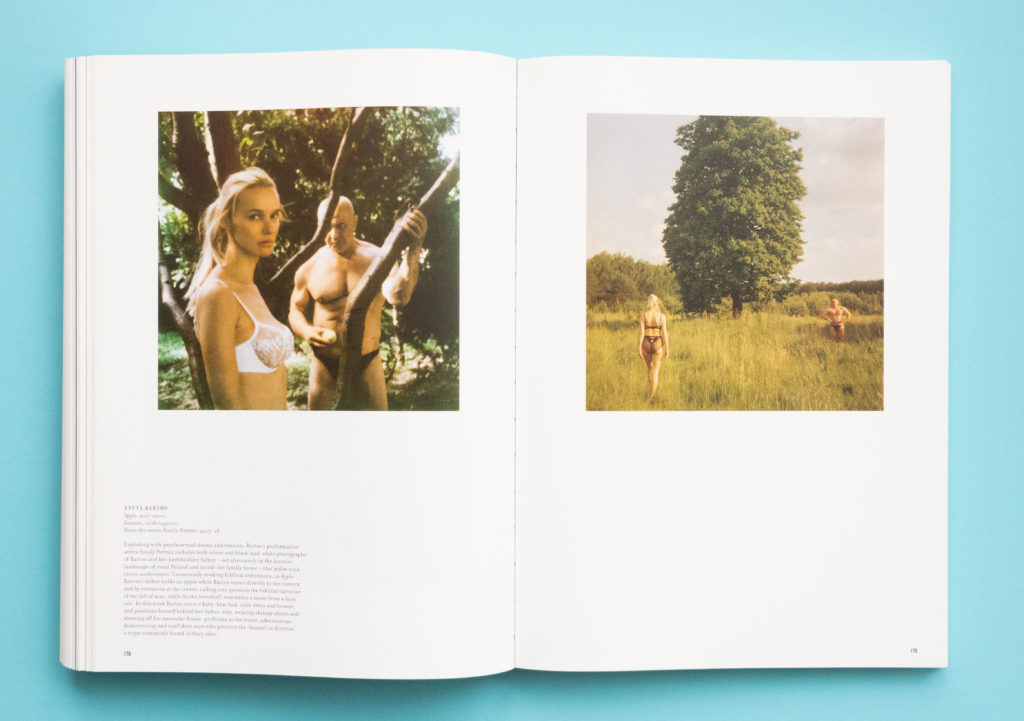

Aneta Bartos’s series, “Family Portrait” (2015-18), is an erotic performance piece featuring the photographer and her bodybuilder father. The photos are taken in the idyllic Polish countryside, with her father wearing revealing shorts while she is in her underwear, both posing mysteriously. The father’s obsession with flaunting his physique to the camera is somewhat comical, and the daughter’s cynical gaze towards the patriarch stands out.

The exhibition continued into the upper level. While the photos in the downstairs exhibition had shown depictions of stereotypical masculinity, the upstairs exhibition was filled with photos that look at masculinity from a completely different perspective.

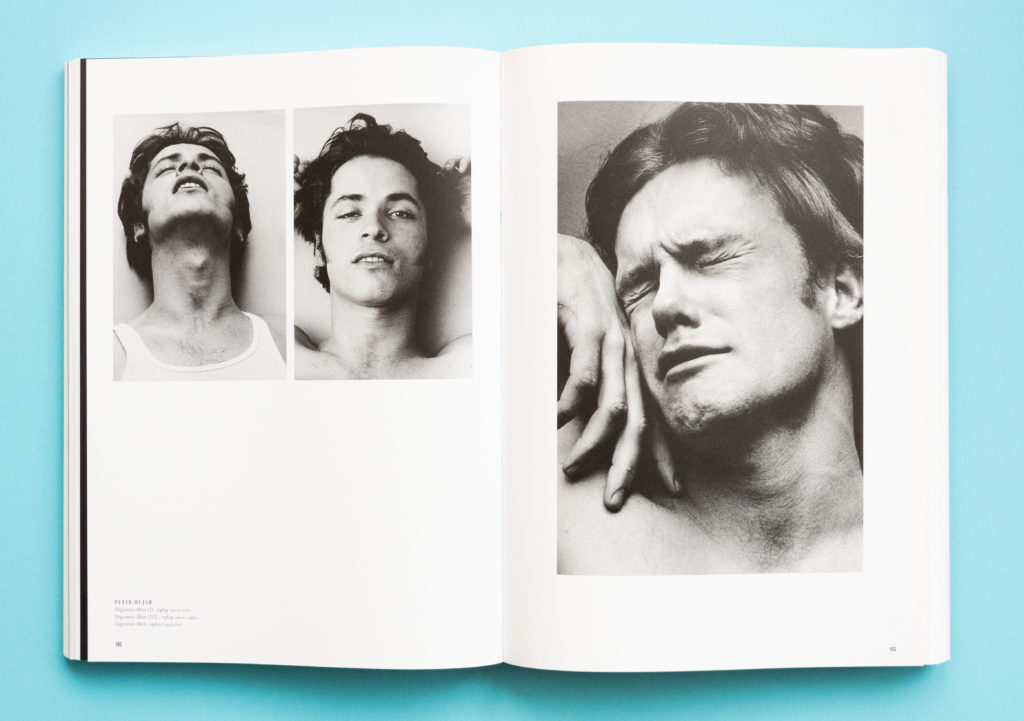

From the “Queering Masculinity” section, I would like to focus on the photographs of Peter Hujar. His series, “Orgasmic Man” (1969) captures men’s expressions at the moment of orgasm, while his series “David Brintzenhofe” (1979-83) shows a man applying makeup and transforming into a drag queen. The ecstatic expressions of the men in the former series reveal a vulnerability that feels distant from masculinity, and could be perceived as feminine according to societal conventions.

Queer is a word that originally meant “strange,” and was once used pejoratively against LGBT people. However, the LGBT community reclaimed the word by using it to refer to themselves in a positive light, which successfully reversed the meaning of the word. Paradoxically, when we recognize that all men alike display the expressions captured by Hujar at ejaculation, we understand how socially constructed masculinity is.

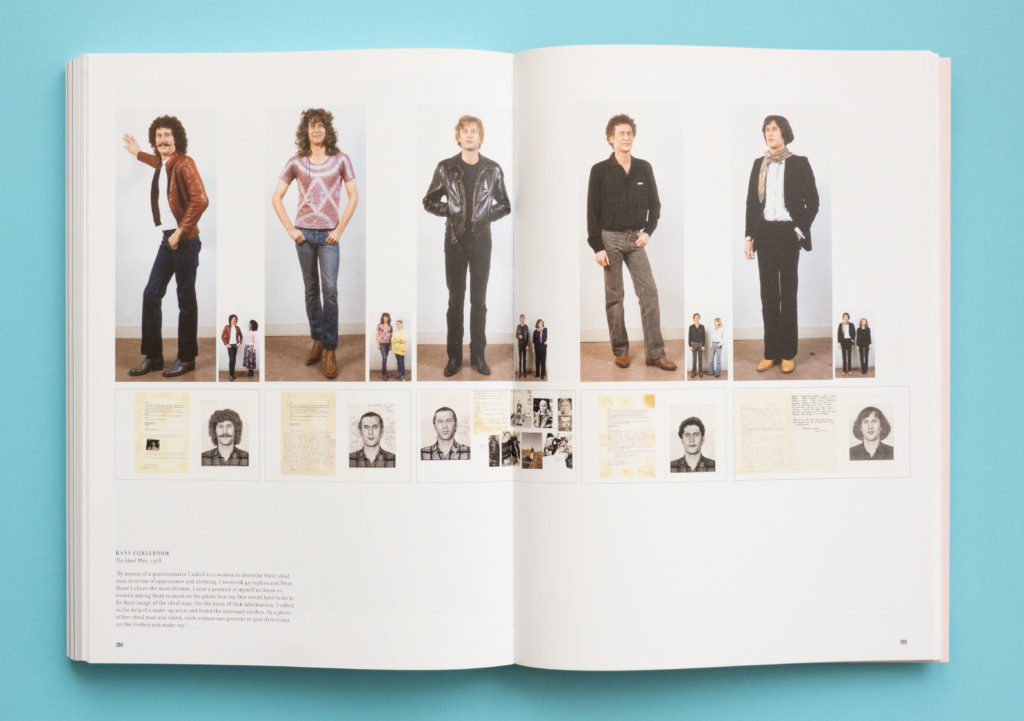

In the final section, “Women on Men: Reversing the Male Gaze,” “The Ideal Man” (1978) by Hans Eijkelboom caught my attention. Eijkelboom surveyed 100 women, asking them to describe their “ideal men in terms of appearance and clothing” through pictures and text. Based on the most diverse responses, he took photos of himself in costume. While some photos can be easily seen as masculine, others appear more feminine or neutral. This series is evidence that at least in the late 1970s, when this series was created, women sought a more diverse range of men who didn’t always fit the conventions of masculinity.

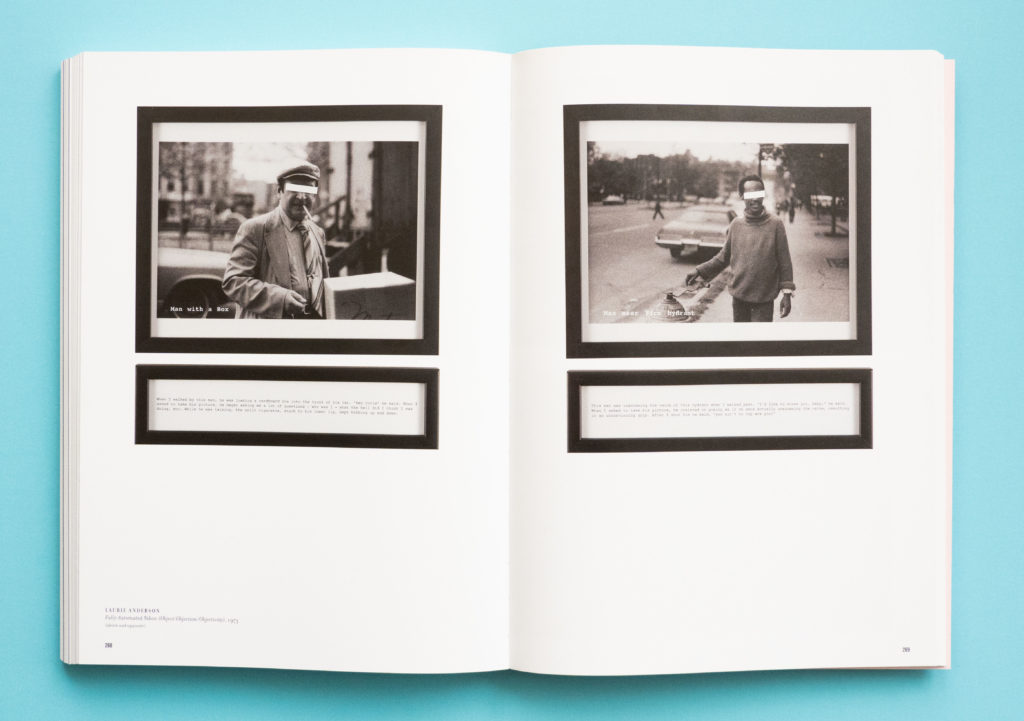

Laurie Anderson’s “Fully Automated Nikon” (1973) documents how men treat women from a woman’s perspective. When women walk outside alone, they’re commonly catcalled by strangers. This happened to Anderson so often that she began to carry her fully automated camera with her. When she encountered catcallers, she would angrily talk back to them, taking a picture as they replied. The men, without exception, would become confused, asking, “Are you an undercover cop?” And simultaneously, they would begin to defend their innocence, as if an invisible ventriloquist had been responsible for their words and actions.

This work is a confirmation of men’s inappropriate behavior towards women, but we shouldn’t forget that this is also part of masculinity. If we analyze the significance of the series’ title, “Fully Automated Nikon,” perhaps it can mean that men’s behavior towards women, in a social sense, is as automated as the camera, and they do not have the will to control it. Anderson saw the existence of a “ventriloquist” behind the men, who only became self-aware after being called out by her, and it can be said that the magic spell that makes this ventriloquist visible is masculinity.

Gender performativity is the idea that before we can even become ourselves, the societal expectations of our biological sex are already imposed on us at birth, and we are forced to “perform” in ways that are considered appropriate for our assigned gender. This concept was first coined by the American philosopher Judith Butler, and it could be seen in this exhibition’s images. Humans are beings that perceive society through a lens. And whether they are aware of it or not, when they try to express themselves in front of the lens, their performance is reminiscent of gender performativity. In this exhibition, this was the case with masculinity.

When I visited this exhibition, I took in the full story intently. The many works analyzed what it means to be a man from an array of perspectives. But with it all displayed so openly, there were many parts that I found difficult to confront so directly. To be honest, as a man, I felt a sense of humiliation. However, to varying degrees, all of these pieces reminded me of my own words and actions when I thought about it, and I appreciate that this exhibition was based on an objective, non-stereotypical analysis.

Here, it’s important to consider the reality that “femininity,” the counterpart of “masculinity,” has been countlessly analyzed from the male perspective, openly displayed, and used by men for their sexual desires and desire to dominate. In other words, the humiliation I experienced through this exhibition is exactly what women around the world have been made to feel. In this sense, the fact that masculinity, something that has received little attention up until now, has been openly dissected through the photographs of the past half-century and exhibited on a large scale is historically significant.

Masculinity is full of contradictions and complexities. There were some vehement criticisms of men in this exhibition, but I don’t think that these criticisms are against the existence of men themselves. As the title of the exhibition, “Liberation through Photography” suggests, this exhibition analyzes how masculinity has been expressed through visual media such as film and photography, while bringing to attention the ways masculinity has been socially constructed and functions in our society. And thus, it frees people from the curse of masculinity.

The only thing that I felt was missing from this exhibition was that it didn’t include many current works. It’s not surprising that masculinity, which was the focus of this exhibition, may be regarded as something of the past, especially in Europe and the United States, where people have been openly talking about it since the 1970s. But while it’s embarrassing to admit, Japan is a country where these discussions about masculinity haven’t even started. In that sense, this exhibition and catalog could be used as a textbook for how to think about gender through photography.

This exhibition is currently being held at Berlin’s Gropius Bau exhibition hall and is scheduled to travel to the Les Rencontres d’Arles in the south of France next summer. Yet, I felt that this exhibition would be fitting in a country like Japan.

Photography Tomo Kosuga

Translation Aya Apton