From the world of business to the field of science, explaining the need for art is on the rise. A world that can be seen from the vantage point of the coronavirus crisis as something unchanging — at the heart of people’s changing emotions, what kind of reactions might they have with regard to art? Galleries, artists, and art collectors, focusing on post-coronavirus art, are considering the image of an emerging new era.

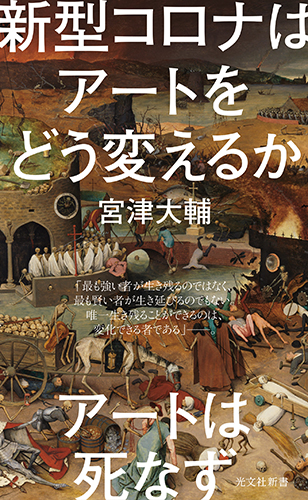

This second article in our series introduces Daisuke Miyatsu, president of the Yokohama University of Art and Design. In 1994, while working as a corporate salaryman, he began collecting art. Developing an aesthetic sensibility through his observation of the art world, he became a visiting professor at the Kyoto University of Art and Design. Over many years, as he continued collecting art, he established personal relationships with both Japanese and foreign artists. Today, Miyatsu also serves on the board of directors of the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. In April 2020, he became president of the Yokohama University of Art and Design, where his research has focused on the relationship between artists and society. He has produced numerous writings in this subject area. Also in 2020, his book, Shingata korona wa aato o dou kaeru ka (How Will the Novel Coronavirus Change Art?), was published by Kobunsha Shinsho. In this book, he discusses various ways in which the novel coronavirus pandemic has influenced contemporary art.

―― Please tell us about your work in the field of art education and especially about your fields of interest in your new role as the president of the Yokohama University of Art and Design.

DAISUKE MIYATSU: In the past, at Softbank, I worked in the human resources department, where I worked on improving the in-house training system and developed the careers of talented senior personnel. Nowadays, as the president of an art university, in addition to managing the institution, I pursue research about relationships between the economy, society, and art. I’m always thinking about how I may help support artists and designers so that they may take part in solving society’s many problems. Ever since I began collecting contemporary art, I’ve continued my close communications with artists and art-related people around the world. I’m also in charge of the “Practical Global Communication Seminar,” an original course that I created, which focuses on how people who have difficult experiences because they do not speak English proficiently and those around the world who do not understand Japanese can arrive at some kind of mutual understanding. The goal is for students to acquire the skills they’ll need in order to be able to present their ideas and their work anywhere in the world by using the full extent of the vocabulary they currently command.

―― In your new book and in your work as an educator, you are interested in the relationship between art and society. Please explain the emphasis you place on the relationship between art and the era in which it is made.

MIYATSU: “Gendai aato” (現代アート) is the Japanese translation of the English term “contemporary art.”

“Contemporary” does not mean only “current.” It can also mean “at the same time.” Therefore, with regard to contemporaneity, that is, to right now, works of art that do not reflect an awareness of the issues or express the concepts of the current time cannot really be referred to as “contemporary art.” With regard to society, how does one have an awareness of the issues? This is important.

Among artists, those who misunderstand the meaning of “contemporary art” are not few in number. Contemporary art might tend to be misunderstood as something from a particular period of time or something stylized, but instead of offering merely style, from outstanding artists whose works convey a sense of contemporaneity, we should be able to understand what “contemporary” means.

――Do young artists in Japan feel that being an artist entails having a certain role to play in society or a particular responsibility in relation to society?

MIYATSU: That depends on the artist, doesn’t it?

For example, in the United States, with the Black Lives Matter movement, or with the presidential-election contest between the conservative Donald Trump and the liberal Joe Biden, and so on, from race and gender to economic policy and diplomacy, it’s becoming apparent that various social issues are being felt in personal ways. Or, similarly, in Hong Kong, with the pro-democracy movement and the national security law that controls one’s personal life. For better or worse, people living in such places are feeling great concern about the situations in their countries and regions.

By contrast, in places where the political situation and public order are stable, the fact is that, for young artists, when it comes to making their work, it’s hard for them to grasp the structure of social problems. However, since 3/11 [referring to the tsunami, earthquake, and nuclear-power-plant accident of March 2011 in Japan], the usual “kawaii art” (cute art) has been in considerable decline, and I think that some outstanding [Japanese] artists have been capturing a sense of Japan’s current situation as they have made their work.

Today, the artist Takashi Murakami, who has become internationally well known, having articulated his notion of “super flat,” which is related to the history of Japanese animation and to a grasp of perspectival space that differs from that of perspective in Western art, is active on a global scale, presenting paintings and sculptures that are based on that concept. Since recognition by the art-market system and creativity overflowing with originality tend to go together, it can be said that he is the one Japanese artist who has achieved rare, worldwide success.

However, for many young artists, the problem of their personal inclusion in relation to society is one that is by no means easy to accurately comprehend. At least I don’t think that Japan, with its superficial peacefulness and security, and its economy, if compared to those of other countries, has fallen into serious circumstances [similar to those of certain other countries]. Therefore, in Japan, one might feel somewhat optimistic. But as many artists of the digital-native generation have been producing outstanding works dealing with games, singularity, or various other senses of values, one can appreciate them with a sense of, “Hey, that’s pretty good!”

―― Meanwhile, artists need opportunities to show their work. From the media, they need the active support of art and culture. However, in Japan, it has been difficult for this kind of critical discussion to materialize, and the media have not been very proactive regarding this concern.

MIYATSU: First of all, there are certain economic issues. The Japanese art market, especially the market for contemporary art, when compared to the broader scope of the economy, is extremely small. In New York, London, and other places with larger art markets, people who are well educated in art, philosophy, and art history and who have expertise tend to find employment in galleries and auction houses, for example. They attract capable people with superior skills, and offer high pay and good working conditions.

Unfortunately, however, in Japan, with its small market, the art world is just not as economically enticing as the financial world. Furthermore, the fact that there are so few critics and so little critical discussion — this is a big problem. As for the evaluation and the historicization of works of art, they need to be assessed in relation to critical discourse.

With this in mind, it’s clear that, with regard to American Abstract Expressionism in the post-World War II period, Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg had authority as critics at a time when New York had wrested art-world hegemony from Paris. However, today, with regard to art education in Japan, the focus continues to be placed strongly on the technical aspects of art rather than on philosophy, aesthetics, and art history.

Furthermore, in Japan, although most artists graduate from art colleges or from art-related, specialized schools, foreign artists who have studied in fields other than architecture and art, such as, for example, anthropology, medicine, engineering, literature, political science, among others, are not few in number. In this way, it can be said that there is a remarkable difference between Japan and Western countries.

Top 10 global museum and art museum visitors in 2018

―― How do you think art is going to evolve after the novel coronavirus pandemic ends? Moreover, when that time comes, what kind of art do you think artists should create?

MIYATSU: No one really knows how much time we’re going to need in order to return to normal life once the pandemic ends. However, not just with regard to artists, but also because, for all of us, naturally our lifestyles and ways of thinking should be changing, to ask “In what ways will artworks be produced?” may actually come to mean “How will we decipher the meanings of works of art?”

The novel coronavirus pandemic is not just something that became widespread. I believe that it is also a “trigger” that is going to drastically change our ways of thinking. From now on, artists will have to make their work while thinking about what are the most important concerns related to the survival of human life. For example, thinking about such problems as microplastics in the oceans or global warming, or problems related to the environment and the Earth.

In Japan, social movements like Black Lives Matter in the United States are still very few, but in setting one’s sights on the future after the pandemic ends, artists should be sensitive to social problems, right? Approval of the diverse sense of values represented by LGBTQ+ people, or the coronavirus-like rise of neoliberalism that economic disparity continues to expand, and so on — because, as it is, many social problems have been abandoned in a half-baked manner.

Meanwhile, I think that [different] regions and the [mainstream] art market are becoming more and more polarized. Thanks to the coronavirus crisis, throughout the world, the disparity between the rich and the poor has expanded, and the tendency for the high-priced works of artists who have already won recognition to increase in value could continue.

As represented by the failures of Brooks Brothers and Barneys (both American companies), and due to the economic decline of the middle class, I think that it’s going to become much harder for artworks worth tens of thousands of dollars to increase in value to hundreds of thousands of dollars. Depending on businesspeople working for companies that are in good shape or on entrepreneurs [who might want to buy art], well-liked works in the high low-price range can be expected to do well.

―― Today, with regard to trends in Japanese contemporary art, what kind of scene is there?

MIYATSU: Prior to the nuclear-power-plant accident that occurred as a result of the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011, in Japanese contemporary art there were many superficial aspects, and, overseas, it was teased for being “cute art.” However, following that tragic disaster, many artists began producing work with an awareness of the good and bad aspects of nuclear power and radiation. With regard to the subject matter of their works, it was a time in which Japanese artists started to adopt a considerably more politically-minded approach.

At that time, with regard to “nuclear” and radiation, the Japanese felt a great sense of anxiety and fear. At first glance, although the level of danger posed by the novel coronavirus appears to be similar, and radiation and the virus have in common that they are both invisible, in fact, they differ greatly. Because the virus is a living organism, it lives within our own bodies. In the words of the philosopher Timothy Morton, “To have a friend is to have a killer.”

On the other hand, when it comes to radiation, it will outlast our lifetimes and will not disappear for a very long time. I feel that, after the pandemic, with regard to the awareness of the issues that artists should consider, moving away from a binary-opposition way of thinking and adopting a more layered, probing point of view will become important.

―― Tell us about your personal collection. Why did you begin to collect art?

MIYATSU: It was 1994, and at that time, while my co-workers and classmates were thinking about buying studio apartments or luxury wristwatches, I made my first-ever purchase of a work of art. Already a longtime fan of Yayoi Kusama’s work, one day, at a museum, I saw one of her “Infinity Net” paintings, and it was love at first sight. Although I was merely standing in front of the painting, I had the feeling that I was literally being pulled right into the picture. From Fuji Television Gallery in Tokyo, which, at that time, was handling Kusama’s work, I used all of my summer and winter salary bonuses to purchase a drawing that she had produced at the beginning of the 1950s.

As my collection grew in size, I met artists and developed a strong interest in wanting to establish friendly relationships with them. Enjoying conversations with artists, dining with them, and sometimes traveling with them, my pleasant experiences coming into contact with the very sources of artistic creativity added up. I got to know the whole family of the French artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster [who was born in 1965], and today I even live in a house that she designed for me.

In the 1990s, especially, I was impressed by the “relational aesthetics” of the French art critic Nicolas Bourriaud. The way of thinking that he advocated — “The relational approach to creating art is inseparable from human relationships and from social contexts” — was resonant, and I remember fondly the home and lifestyle I have constructed along with my artist friends.

Today, there are more than 400 works of art, including video and new-media works, in the collection that I have amassed. I respond to requests from museums around the world for works to be loaned, and there are works in my collection that travel around the world more than their owner does! But, as for myself, art-collecting activity is not merely about acquiring artworks; through meeting artists in person, chatting with them, and sharing meals and traveling with them, it’s also about gathering memories [of these experiences]. I think that, as far as the relationship between society and art is concerned, frankly, it has to do with friendships.

―― Please share with us some of your observations about the broader contemporary-art market in Asia.

MIYATSU: Including Japan, it still cannot be said that Asia’s contemporary-art market has fully matured. But buying power driven by China and the oil-producing countries is large, and in Shanghai and Hong Kong, and in Taipei, too, important art fairs are taking place. Art from Indonesia, China, and India is attracting international attention, and along with these developments, each country’s market is showing signs of brisk activity.

Right now, due to the novel coronavirus pandemic, many art fairs have been taking place online, but I’ve been hearing that two actual fairs that took place in Shanghai last year, in November, did extremely well. I think that, as soon as the coronavirus crisis comes to an end, Asia’s contemporary-art market will also continue to develop. Stay tuned. I think that, by no means has there been any great loss.

Daisuke Miyatsu

Born in Tokyo in 1963. President of Yokohama University of Art and Design. Member of the board of directors, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. His research focuses primarily on the relationship between art and the economy and society, and he is also a renowned collector of contemporary art. He has served as a member of the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs’ Study Group on the Overseas Dissemination of Contemporary Art, as a juror for the Asian Art Award 2017 and Art Future Prize – Asia New Star Award 2019, and in other roles. He is the author of Let’s Buy Contemporary Art (Shueisha), The Age of Art × Technology (Kobunsha Shinsho), and Contemporary Art Economics II: Art in the Age of Depletion of Oil, AI, and Virtual Currency (Wates). He has appeared on NHK General TV’s Close-up Contemporary+ and NHK News, Good Morning Japan programs, among others. He is also widely active in the media.