The quest for Yusuke Takahashi’s creative process

In 2020, a pandemic that no one could’ve predicted the year before ravaged the world at large. We’re still leading a life driven by anxiety and apprehension. In an era where gray skies loom over our heads, one Japanese creative director took on a new challenge to propose his vision of the future.

The designer in question? Yusuke Takahashi. He became the artistic director of ISSEY MIYAKE MEN in 2013 at the young age of 27. During his time there, with Paris as his stage, he had something to prove to the world. In February of last year, Takahashi left MIYAKE DESIGN STUDIO, where he worked for around a decade, and established his own company. Said company and his brand share the same name, CFCL.

How did he design his debut collection? What did he see, hear, feel, and think during the process? What is his creative process in the first place? Let me begin by telling you the story of his student days to clarify these questions.

Discovering a creative identity in school

The magic of fashion design, the type that draws people in, is born when a designer can create a concrete brand identity. The designer’s childhood, teenage years, and their unique experiences as a student creating garments inform this magic.

I begin by asking Takahashi about his student years to find out the source of his creativity.

Takahashi is an alumnus of Bunka Fashion Graduate University (BFGU). Before he got into BFGU, though, he arduously studied fashion design and art criticism in London. Takahashi says, “When I was studying in London, they didn’t look for the quality of sewing. They prioritized students cultivating core concepts, identity, and social awareness.”

After his time in London, he studied to acquire foundational skills to create clothes at BFGU. Takahashi soon discovered that one of the primary criteria was the quality of sewing. Compared to his BFGU peers, who spent years learning the craft of clothes making, he felt his skills weren’t at their level. He felt distressed about the situation, but then one class changed all of that. It was on 3D computer-developed knitting via a “wholegarment” machine created by Shima Seiki. From that point onwards, he found a way out thanks to computer-developed knitting.

However, this wasn’t Takahashi’s first go at creating knitwear. The university back in London had a flat knitting machine, and he would construct garments over and over using unusual materials such as silkworm gut (a white, translucent thread traditionally used for fishing) and wire. He then came up with the idea to incorporate silkworm gut using a 3D computer: “I thought, this is it!”

After seeing the complete knitwear garment, Takahashi began to feel confident. That very confidence led him to hone his skills at computer-developed knitting, which in turn led him to receive the 83rd Soen award for his clothes’ originality. With computer-developed knitting, the conventional concept of patternmaking or sewing doesn’t apply, as the function is to knit. Meaning, it was no longer of use for instructors to ask Takahashi for high-quality sewing. With that weight off his shoulders, the only thing left was to focus on his work’s originality. In short, Takahashi overcame an unfavorable situation by carving out a new criterion instead of conforming to an already-existing one. With this new asset of his, he was then able to show what he could do.

Computer-developed knitting reminiscent of programming language

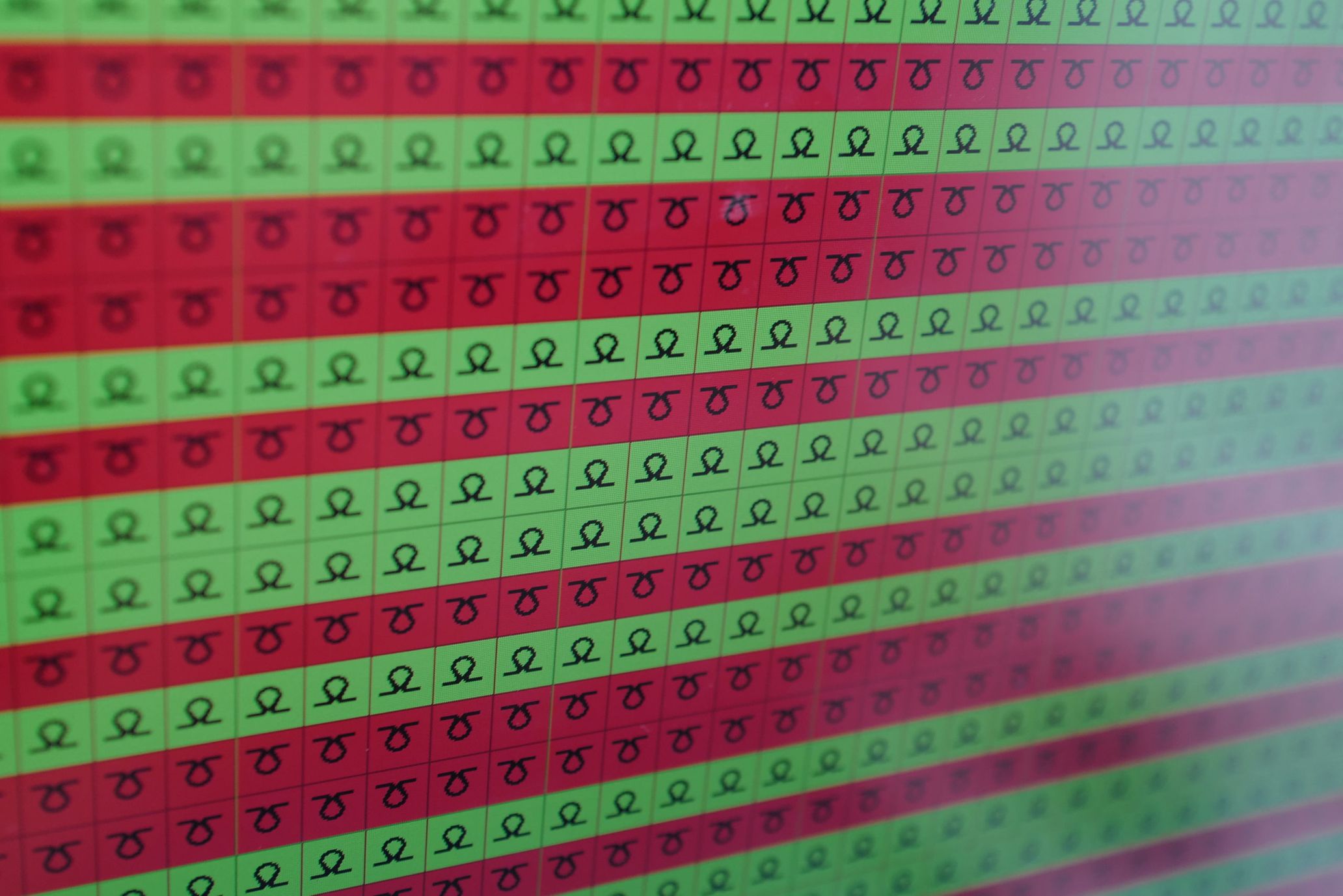

How exactly does computer-developed knitting work? When I ask Takahashi this, he shows me a photo of a monitor screen with what seems to be systematically-placed knit “loops.” Seeing it reminds me of programming language on a monitor screen. The lined-up loops depicted in the photo evoke the same feeling as programming numbers, symbols, and letters, which may seem insignificant at first sight, but are essential.

He draws his designs on an iPad and uses his rich experience with computer-developed knitting to create a file with the required shapes and estimated measurements. He then sends it to a programmer who turns that file into data, integral for any wholegarment machine to knit a garment. The infinite loops onscreen are the manifestation of this process.

Takahashi picks up a seamless dress from his debut collection, made with two types of knitting structures. He proceeds to talk about how he conceptualized the design.

The two types are 4 x 4 broad rib stitches, where every other row is purled, and 2 x 2 garter stitches. The dress has a crinoline-like silhouette, meaning the dress dramatically billows outwards from the waist down. Despite its impressive look, the construction is quite simple. Takahashi cleverly uses each fabric’s different elastic functions — broad stitches shrink horizontally, while garter stitches shrink vertically. By programming many seamless darts around the waistline, where one knitted fabric shifts to the other, he’s able to achieve the voluminous, elegant crinoline-like shape.

People usually accept the conventional way things are done and make clothes accordingly, but Takahashi reconstructs traditional methods to beget something new. His anecdotes from his days at BFGU is a testament to that. By going against the grain, he brought forth a unique perspective to design.

The rise of innovation from the space between sensibility and thought

Now, how did CFCL’s debut collection come about? Takahashi explains, “Most of the time, I figure it out as I go.”

This answer comes as a surprise because it doesn’t fit the image I’ve created of him as I listened to him talk. Nonetheless, he continues to elaborate on the brand’s concept and theme. “The brand’s concept and theme are separated. The concept doesn’t change, but the brand itself? Well, what makes a brand? The theme represents the season. Some people mix up the concept and theme, but there’s a distinction between the concept and theme at CFCL.”

Takahashi points out that CFCL’s debut collection theme was an exception. “The theme of our first season is also the statement of the brand, so the theme and concept for this one are very similar. In that sense, it might be a little different from the other seasons.”

The theme of CFCL’s Vol.1(2021SS), its first season, is Knit-ware. He didn’t set the theme from the beginning, as he discovered it during the collection-making process. One day, while looking at a seamless knit dress made with temporary stitching a la computer-developed knitting, the fact that the dress’s smoothness looked like pottery came up in conversation. Takahashi felt like pottery was the key to the brand’s collection theme. And so, he worked to conceptualize that. He brought the collection to another level by basing the collection’s color palette off of the glaze on pottery.

I feel like innovation points to ambiguous yet powerful things that words can’t describe. When words can describe something, then that’s not innovative. Takahashi felt like he had a sensibility that couldn’t be articulated, and so he figured out the collection intuitively, instead of forcefully trying to explain the theme only with words.

Clothes constructed in this manner carry a message. Sure, that message might differ from conventional fashion, but that could potentially turn into the source of innovation. Sparks of inspiration become elevated as design when logic is applied to the message. And this is how a collection could obtain an even more profound depth.

By going back and forth between sensibility and thought, a particular space emerges. Isn’t that where innovation arises? Takahashi isn’t solely inclined towards his sensibilities, but he’s also not solely inclined towards his thought process. Also, he doesn’t have an ego that demands his worldview to be prioritized. Takahashi finds the source of design in everything, from the things he sees to the things he hears, and creates meaning and value. And so, he creates collections together with his team.

Clothing For Contemporary Life

just for you

I’d like to pay attention to one look from CFCL’s first collection; a dress reminiscent of crinolines and bustles. I inquire if old European clothes inspired the shape.

He answers, “In any era, even today when people look for practicality, it’s important to be conscious of femininity in women’s clothes. This dress accomplishes that by having a crinoline silhouette that exaggerates the difference between the waist and hips. By attaching that silhouette to the tight shirt-like top, we’re suggesting it’s a dress that can be worn with comfort. This silhouette is the result of combining a ribbed fabric that cinches you in painlessly, and a fabric created by a knitting machine with maximum broadness.”

I had mistakenly assumed 19th-century European clothes inspired the dress. But it was created with a practical approach that took the materials’ characteristics into account. It doesn’t stop there.

“In this day and age, it’s especially crucial for women to look beautiful, but with ease. I think we shouldn’t establish trends or themes, only then to design clothes that are hard to wear afterward. Regarding menswear, many designs still maintain details that used to have a function back in the day, such as military wear. I try to make it a point to ask myself if such things are still necessary today.”

One can see Takahashi’s ability in this very conversation. He defines ideas. He interpreted “elegance” as “the difference between the waist and hips” with the dress. Before that, he spelled out the difference between themes and concepts. It seems as though this is a useful approach to designing. Instead of leaving ambiguity in ideas, he attaches a clear definition to them and manifests them. There aren’t many fashion designers that choose their words intensely to the extent Takahashi does.

I then ask about another look. The look in question is a pair of men’s pants that puff outwards from the knee down. It’s quite rare to see a man wear such a radical design, and I had wondered if it was going to fare well in the market when the collection came out.

Takahashi quietly answers: “The person wearing the pants should think about whether they’re hard to wear. It’s unnecessary for the person not wearing them to think about that. One guy actually bought the pants and said, ‘I’m going to wear them every day.’ What you said is an example of unconscious bias. Whoever wants to wear them should simply wear them.”

Takahashi’s response makes me realize that I had adhered to preconceived notions without knowing it.

Forward-thinking fashion proposes garments that are appropriate to alternate lifestyles of a new era. Running a brand is akin to running a business, and it’s vital to think about how marketable a product is. But by focusing too much on market appeal, one can’t propose an alternate way of living, which is the most integral aspect of forward-thinking fashion. This is because genuine innovation doesn’t exist in the present. Takahashi is trying to create a market of the future with his forward-thinking spirit.

People might think new kinds of fashion aren’t exactly necessary in our world today, as we all live in uncertain times because of coronavirus. But the act of wearing clothes could boost our mood and give us the energy to live through right now and tomorrow. We need the power of fashion design, which provides us a vision of the future and opens up possibilities of another way of living. And this is precisely because we live in a time where it’s hard to have hope for what lies ahead.

Takahashi grabs the space between sensibility and thought with his palms. When he opens them up, what lies there is an innovation that lights up the future. CFCL exists to create clothing for those that live a contemporary life.

Yusuke Takahashi

Yusuke Takahashi founded CFCL, a forward-thinking and sustainable brand that uses the ingenious technology of 3D computer-developed knitting, in 2020. The brand incorporates upcycled materials to create quick-drying garments that can be washed at home. With a focus on sophisticated knit dresses, they put forth clothes that make contemporary life both comfortable and fun. From January 27th, CFCL’s first collection will be released via a pop-up shop at Shinjuku Isetan Men’s department store and the main Isetan department store. The collection will then be sold on their online store, starting from February 1st, and other stores that carry their items.

www.cfcl.jp

Instagram:@cfcl_official

Photography Shinpo Kimura

Translation Lena-Grace Suda