The Hara Museum of Contemporary Art is set in a stylish Western-style mansion in the residential area around fifteen minutes away on foot from JR Shinagawa Station. The museum, which has been a pioneer in contemporary art for 40 years, was permanently closed on January 11, 2011. In the spring, the “Hara Museum ARC,” which used to be an annex situated in Shibukawa City, Gunma Prefecture, will open after undergoing renewal work to consolidate its operations.

Most of its characteristic permanent pieces will be relocated, no need to despair, although the people attached to the cozy atmosphere of the building itself aren’t few. In this article, we will explore the surprisingly lesser-known history of the museum and its building, the last exhibition held in it and its future.

The building was initially built by an entrepreneur at the request of his wife

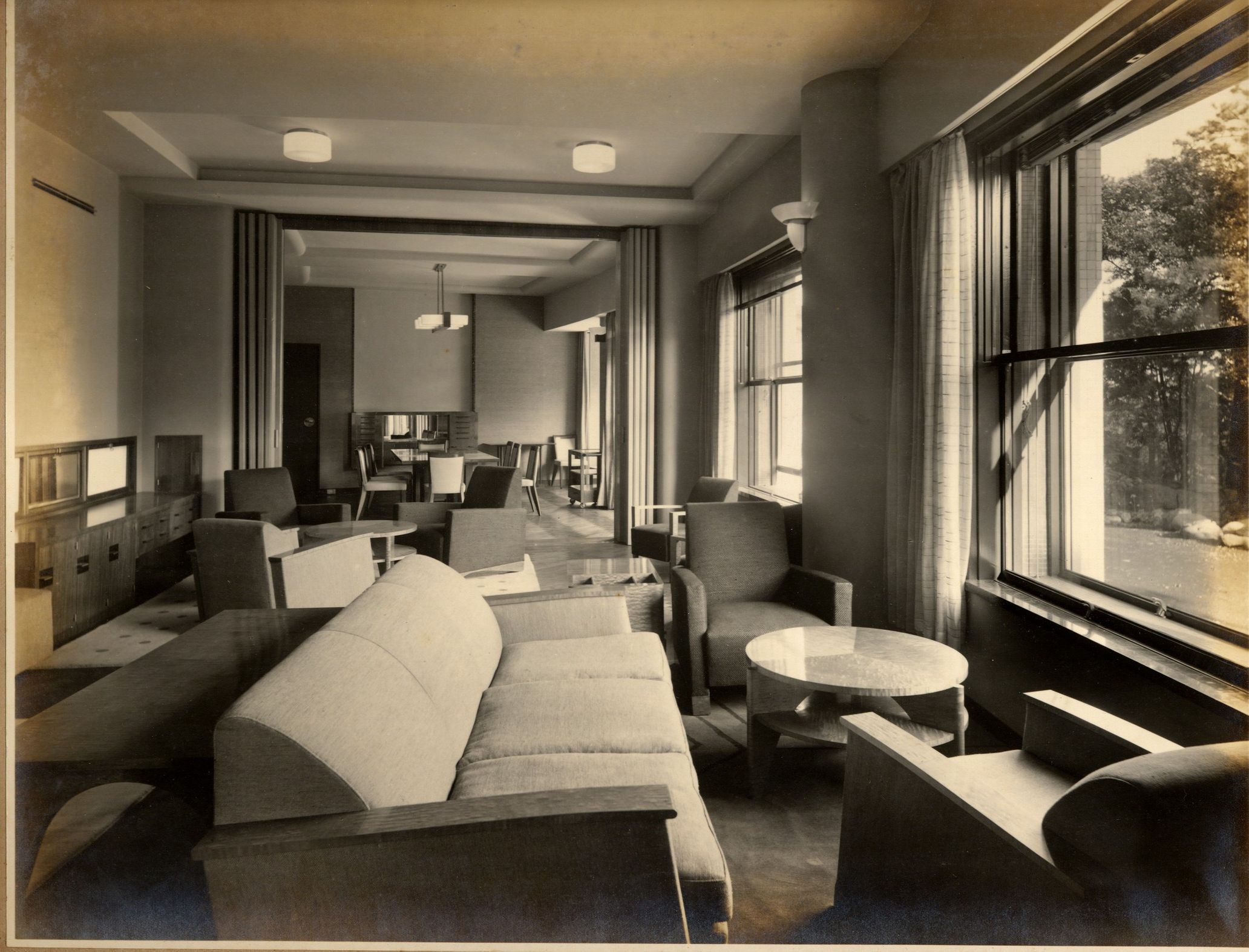

The building of the Hara Museum in Shinagawa was built in 1938, 41 years before it opened as a museum in 1979, and the whole area around it was originally the piece of land where the Hara family’s mansion was for generations. It is said that in 1982, Rokurō Hara, an imperial loyalist at the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and entrepreneur during the Meiji and Taishō eras, took over the land previously owned by Saigō Jūdō, Saigō Takamori’s young brother.

Rokurō was the president of the 100th National Bank (which later merged with Mitsubishi Bank) and Tobu Railway, also contributing to the establishment of Tokyo Electric Light (currently TEPCO) and the Imperial Hotel. Along with Shibusawa Eichi, Yasuda Zenjirō, Okura Kihachiro, and Furukawa Ichibei, Rokurō is known as one of the “five men of the Japanese business world,” as well as a notorious art collector. His collection includes works such as Sesson Shukei’s “Resshigyofūzu,” Kanō Eitoku’s “Kozu,” Maruyama Ōkyo’s “Yodogawa Ryōgan Zukan” and many more.

Kunizō Hara became Rokurō’s son-in-law and succeeded the family. He was active as an entrepreneur from the Taishō era to the middle of the Shōwa era, acting as chairman of Tokyo Gas, Japan Airlines and president of Teito Rapid Transit Authority (currently Tokyo Metro). When Kunizō inherited the land, there was only a Japanese-style house on the plot, and at the request of his wife Taki (Rokurō’s eldest daughter), he built a Western-style private residence in 1938, which later became the Hara Museum’s building.

The building and its different roles

Designed by Jin Watanabe, a leading architect at the time who worked on the Tokyo Imperial Museum (currently the Tokyo National Museum’s Main Building) and K. Hattori (currently Wako Ginza). The Hara residence was built as a modernist building adopting essential elements of Bauhaus and Art Deco. In 1941, the Pacific War started, and the family was forced to evacuate the residence, which was requisitioned by the GHQ, and used as a dormitory for US military officers after the war. As an aside, all the other buildings designed by Jin Watanabe have been requisitioned by the occupying forces: for example, the afore-mentioned K. Hattori became a shop exclusively for military officers, the Dai-ichi Seimei Hall in Hibiya became the GHQ headquarters, and Hotel New Grand In Yokohama became a military dormitory, where MacArthur also stayed.

After the conclusion of the San Francisco Peace Treaty in 1951, the Hara residence was also used by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, later becoming the Philippine Embassy, and the Ceylon Embassy (currently Sri Lanka). After that, the house stayed vacant for more than ten years and was almost demolished to build an apartment complex, but the demolition was canceled due to the concrete being too sturdy. When Toshio Hara, Kunizō’s grandson, thought of opening a museum of contemporary art in the 70s, he had no intention of using the abandoned building. Toshio later visited the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, which building was once a private residence repurposed to be a museum in 1856, and was deeply captivated by how comfortable it felt; inspired by his experience, he decided to convert the Hara residence into an art museum.

Thus, the Hara Museum opened its doors for the first time in December 1979. After that, under the supervision of architect Arata Isozaki, the cafe, office building and hall were added to the main one, but the exterior appearance was mostly untouched. In 2003, the dramatically-fated building was even recognized by DoCoMoMo, and since then, it has been critically acclaimed for its architecture.

The charm of the Hara Museum beyond architecture and permanent installations

With its building being a former residence, the Hara Museum attracted many artists and held many exhibitions that made the best use of its main characteristic. This was especially notable in the permanent installation rooms: one example would be Jean-Pierre Raynaud’s “L’Espace Zero,” initially a greenhouse that was later covered in white tiles. The former men’s toilet also became Tatsuo Miyajima’s “Time Link,” while the toilet for visitors became Yasumasa Morimura’s “Rondo;” the darkroom turned into Yoshihiro Suda’s “The Water Unfit for Drinking—Camellia,” and the bathroom into Yoshitomo Nara’s “My Drawing Room.”

Photography: Keizo Kioku

Production Assistant graf

Photography Keizo Kioku

Of course, the Hara Museum’s magnificence is not limited to its building: in 1977, Toshio founded the Foundation Arc-en-Ciel, two years before the museum’s opening; by that time, he was able to purchase about 200 works, focusing on his art collection since then. The collection now amounts to more than a thousand pieces, including works from artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jean Dubuffet, Atsushi Kawahara, Yayoi Kusama, On Kawara, Yayoi Kusama, Ushio Shinohara, Nam June Paik, Ai Weiwei, Nobuyoshi Araki, Jan Fabre, Izumi Katō, William Kentridge, and Kohei Nawa.

In 1980, the year after the museum opened, “Hara Annual,” a special exhibition to introduce young artists started. In the 90s, some exhibitions planned by the museum, such as “Shiro Kuramata’s World Exhibition,” began to tour overseas, thus improving the museum’s recognition overseas as one of Japan’s leading entities in contemporary art.

The artists who held solo exhibitions in the Hara Museum include Sophie Calle, Miwa Yanagi, Camille Henrot, Tabaimo, Adriana Varejao, Pipilotti Rist, Tomoko Yoneda, Jim Lambie, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Michaël Borremans, Nicolas Buffe, Cy Twombly, and Kishin Shinoyama.

Photography Osamu Watanabe

The biggest reason why the Hara Museum was closed is the aging of the building, which is 80 years old. It was repaired often, but the damage caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake was extensive. Furthermore, there is no elevator, the stairs’ handrails are low, so it isn’t following barrier-free and universal designs. On top of that, the frontage is too narrow, and the number of large-scale pieces that are difficult to deal with has increased over time. It is unrealistic to rebuild as an art museum too, due to the regulations of the Tokyo Metropolitan Ordinance, where the conditions for attracting customers are strictly set. Therefore, it was decided to close the museum 40 years after its opening.

For posterity: the last exhibition in Shinagawa

From September 19, 2020, to January 11, 2021, the final exhibition “Time Flows: Reflections by 5 Artists” was held at the Hara Museum. In addition to the photographs by Tomoki Imai, Tamotsu Kido, and Tokihiro Satō, the main pieces of the exhibition, Masaharu Satō’s animation and Lee Kit’s installation were also taken from the museum’s collection and displayed.

Taiwanese-born, Taipei-based artist Lee Kit’s installation was initially showcased for his 2018 solo exhibition “We used to be more sensitive.” at the Hara Museum and joined the collection. The canvas-looking cardboard reads “Selection of flowers of branches.”

Photography Tamotsu Kido

Tamotsu Kido, who captures the “sudden senselessness” of things that deviate from their original roles within everyday life, displayed 46 photographies in various sizes, intending to analyze the mysteriousness in what we can see, what exists. Vividly and humorously, Tamotsu shoots a variety of imageries far from the mainstream of modern society, such as cows looking through holes in artificial objects, or decommissioned cars covered in blue sheets.

Still in his mid-40s, Masaharu Satō passed away in the spring of 2019; nonetheless, his piece “Tokyo Trace,” which was initially showcased for his solo exhibition “Hara Documents 10 – Masaharu Sato: Tokyo Trace,” was also displayed for the Hara Museum’s closing exhibition. Masaharu recorded footage of Tokyo heading for the Olympics from five years ago and traced a part of it, blurring the gap between fiction and reality through the use of live filming and animation at the same time. In the solarium at the back of the exhibition room, an automated piano was playing Debussy’s “Clair de Lune,” symbolizing the tracing of sound.

Tomoki Imai displayed pictures from his series “Semicircle Law,” which he shot from several mountain peaks within 30 kilometers from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, pointing the camera in its direction. For this exhibition, he included new shots taken from the Hara Museum, reminding us that the accident persists.

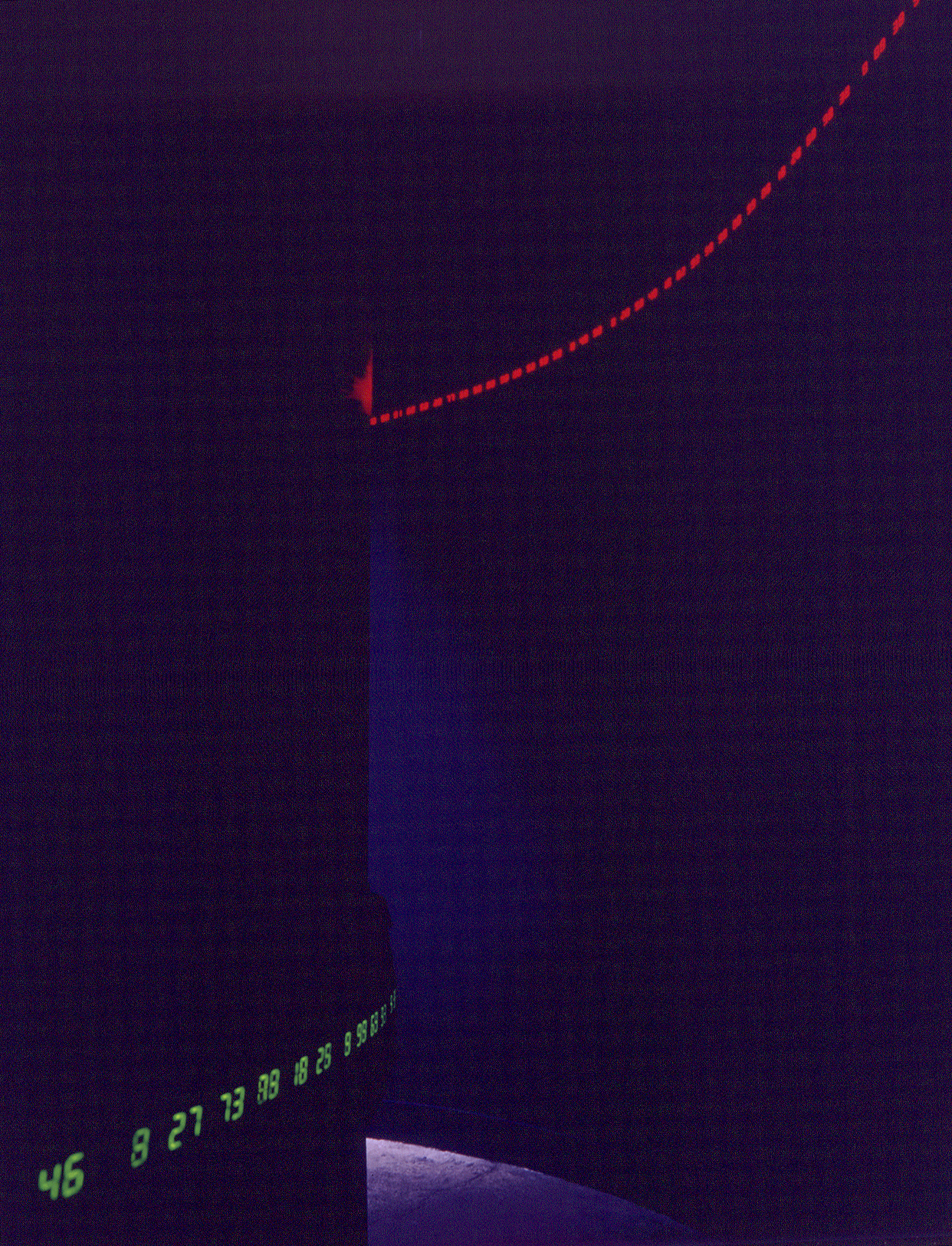

Tokihiro Sato exhibited his new series “Photo-Respiration,” in which he makes use of long exposures techniques to capture the light traces of mirror and penlights he creates while moving around in front of the camera.

Looking through these artists’ works of art shedding light on their time and space, they are etched in our memories together with the Hara Museum and its closing, with the hope it will connect to our futures.

Reopening at a plateau resort

As an annex to the Hara Museum in Tokyo, the Hara Museum ARC was opened in 1988, around Ikaho Onsen in Shibukawa City, Gunma Prefecture; adjacent to the Ikaho Green Farm, the black and sharp building designed by Arata Isozaki shines in the abundant nature. In addition to the three exhibition rooms filled with natural light, there is a special exhibition room known as the “Kankai Pavillion,” based on Shoin-zukuri, while the outdoors are filled with permanent installations by artists from Japan and abroad, including Andy Warhol and Olafur Eliasson; another incredibly cozy location.

Photography Ichiro Katagai

This venue also has a collection storage room, and the exhibitions so far have been organized around the works in the museum’s collection. Currently, the location is closed due to renewal work and is scheduled to reopen this spring. Most permanent installations from the Hara Museum in Shinagawa will also be relocated to this venue (Yoshihiro Suda’s “The Water Unfit for Drinking—Camellia” will not be relocated due to duplicability issues, but the sculptures will be preserved). Located in a plateau resort within day-trip distance from the city center, this venue will engrave the new history of the Hara Museum.

Photography Yuichi Shiraku