Culture can be born out of a specific time and place, and yet, it possesses the ability to become timeless. In this series, “時音” TOKION invites people who are shaping culture today to talk about the past, present, and future.

For this installment, we spoke to Hikari Ōta of Bakushō Mondai, who published a compilation of essays last December called Geinin Jingo. Ōta approaches a wealth of topics distinctively, such as the entertainment industry and drugs, freedom of expression, the masses and television, women leaders and coronavirus, the postwar regime, and prime minister Suga. The book is an insightful glimpse into his thoughts and goes deeper into each subject compared to his television and radio appearances. We illuminate his ideas on comedy in today’s landscape while taking Geinin Jingo into account.

Demanding political correctness from comedians isn’t a bad thing

——It seems as though people demand comedians to be more politically correct in recent years. How do you feel about this?

Hikari Ōta (Ōta): Comedians create comedy by going against the grain. We can make people laugh by deviating from social standards that say, “You can’t diverge from this.” That’s why people demanding political correctness isn’t a bad thing for us comedians.

Many people say, “People didn’t nag about compliance so much in the past. It was easier to do things more freely.” But the difference between what people considered compliance back then and today is minor. Even in the past, some things were off-limits. You have to gauge what’s permissible and what’s not. It’s our job as comedians to be conscious of how far we can go without breaking the broadcasting code. Like, “This is fine” and “This isn’t fine.” The only difference is how people set the benchmark today, but what we’re doing isn’t that different from before.

——I see. So, you mean how far you can deviate from social values changes according to the era?

Ōta: Well, I’m sure what people consider to be socially and morally correct is narrower now, but it’s about how we can poke fun at that.

——How do you judge what’s okay and what’s not when you create a comedy routine?

Ōta: I do it subconsciously, but I take in the zeitgeist. In terms of Bakushō Mondai, I adjust [my jokes] according to Yuji Tanaka, the straight man.

For instance, the prime minister, [Yoshihide] Suga-san had a hoarse voice once. If I were to say, “Did he get infected by corona?” how would Tanaka respond? Would he say, “Don’t be inconsiderate,” “He might’ve, but you know you can’t say that,” or “You’re still going on about that? That’s old news”? Tanaka is the voice of reason between us, so whether we get laughs depends on how far I can run with what he says. If Tanaka’s common sense doesn’t align with the audience, then they’d be like, “Tanaka doesn’t get it!” and not laugh.

——I get the impression you say what’s on your mind on TV, but it seems like you think about the viewer too.

Ōta: I’ve always believed that to be my fate. If I don’t keep them in mind, then people won’t laugh.

The desire to express one’s true thoughts

——In 2020, the phrase “Comedy that doesn’t offend anyone” was popularized. In Geinin Jingo, you write that comedy is born from hurting other people’s feelings.

Ōta: The most amusing thing is when we made a comedy routine based on how phony people sound when they say, “I don’t like comedy that insults people.” It was so satisfying. Some people proudly say they’ve never laughed at the expense of someone, but that’s impossible. I speak about this in Geinin Jingo, but people like that usually bring up Charlie Chaplin as an example of politically correct comedy, but Chaplin wanted to poke fun at that contrived sense of moral superiority. Everyone has their true thoughts and then their facade. You can express people’s fronts in many ways, but we want to get into the nitty-gritty parts.

——You make fun of Tanaka-san’s appearance often by calling him short. I presume you get criticized for how you make fun of appearances.

Ōta: The only difference is whether you vocalize something. This sort of humor is everywhere. If you shift your perspective, you’ll realize [thinking about something and pointing it out] are the same thing. But somehow, one is considered politically correct. Imagine Tanaka onstage trying to reach something on top of a shelf and failing to do so. At first glance, it may look like self-deprecation, but in reality, the onlooker is laughing at a person for being short. But if the comedian tries to hide that fact, they can. So it’s pretty deceiving.

——There’s this tendency to conceal the truth. Do you acknowledge that aspect and channel that into your comedy too?

Ōta: Yeah. Aren’t those that boast “There’s no bullying in our school” the most suspicious ones? It makes you think, “There’s no way that’s true.” I feel like those types of people look away from the problem.

To be laughed at or to make people laugh

——When it comes to whether comedians are being laughed at or making people laugh, it seems like you try to be laughed at. Lately, people think the most imperative thing for comedians is for them to make the audience laugh. What do you think about that?

Ōta: Ultimately, what we’re providing is entertainment for the people. It’s not like we’re in academia or doing anything noble. So, I don’t think I’m making anyone laugh. Of course, each comedian has their thoughts about this. But for me, my comedy comes from my immaturity or making myself the butt of the joke. Hence me feeling like I’m being laughed at.

——Comedians are held in higher regard than before.

Ōta: Comedians’ status changed massively ever since Beat Takeshi (Takeshi Kitano) came onto the scene. During his Two Beats days, society didn’t like him. Like his “Make sure to strangle your parents before you go to sleep” one-liner, he said things that are taboo by today’s standards. But people loved it. And then, Takeshi-san went from being a comedian to an actor. He got to the level of acting in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, and got nominated for an award at Cannes.He won awards at Venice (Film Festival) and Cannes for his own films and became well-known worldwide. But he’s still mischievous. We were drawn to how cool he was. He taught me that people who can do comedy have so much talent. But the thing is, it’s harder to do comedy once the social standing of comedians goes up. It’s a mixed blessing.

——Do you think M-1 Grand Prix, an annual competition for comedy duos, has contributed to bettering comedians’ social standing?

Ōta: As Bakushō Mondai, we went on many TV competition shows. We got the right to be on TV at the beginning [of our career]. Going on TV is a necessary step for young comedians to make it. But this sort of “stand-up routine fit for M-1” is becoming something to study, more and more. What we’re doing is deviating away from that. Because there’s some history behind M-1, it’s hard not to turn it into an academic pursuit. Rakugo (traditional comic Japanese storytelling told by one storyteller) became classic entertainment and not mainstream. Then, Iromon (various forms of entertainment aside from Rakugo) was born so that those with no knowledge about Rakugo could casually enjoy a show at a hall for such events. Manzai (Japanese stand-up by comedy duos) for the masses was born after that. Manzai, which emerged as Iromon, is on the verge of becoming an academic study. Part of me thinks things shouldn’t go down that path.

“…I’m not interested in platforms where anyone can say anything. If I become unpopular, then it’s the end.”

——Online news outlets often report on the things you say on Sunday Japon, a Japanese TV show. I assume you’re unable to mention everything you want to within such a short time. Is there anything you’re careful about re what you bring up?

Ōta: When I first started appearing on Sunday Japon, I thought, “I’m just going to use all of this material for our Manzai jokes,” so I restrained from giving my opinion. The same goes to Hikari Ōta’s If I Were Prime Minister of Japan… Secretary Tanaka (a Japanese entertainment debate show), but I’m the type of person who can’t compartmentalize what I should and shouldn’t say. Before I knew it, I was saying whatever I wanted.

Now, I make remarks knowing they’re going to cut out some parts to a certain extent. I might say something I shouldn’t, but isn’t that better than the show ending as expected? Because it’s live television, I have times where I’m like, “This isn’t exactly the right words,” but if I don’t say what’s on my mind before the program ends, then I’d regret it. I might get criticisms, but I try to say what I think.

——Recently, there’s an increase in people verbally attacking others on social media. What are your thoughts on that?

Ōta: I think we need to confront the issue with social media more seriously, but it feels like we’re moving slow. Regarding cyberbullies, a lot of them are anonymous. If social media is a public space, then I think we need to get rid of anonymity. Also, you know how Twitter suspended Trump’s account? Should American presidents be allowed to say their subjective opinions freely online? That’s what I question. Japanese politicians all have Twitter now, but I constantly feel like, “Wait, hold on.” I think Japanese politicians should make a clear distinction between their public selves and private selves.

——Because we have freedom of speech, that also means some people will say discriminatory remarks.

Ōta: This goes back to what I was saying about TV compliance; when TV was first introduced, things weren’t as strict. I think people saw television as this spectacular theater. Then, the Broadcasting Ethics & Program Improvement Organization and third-party organizations started to look into television content. That industry began to categorize what was permissible and what wasn’t. The internet and social media are a mixture of good and bad right now, but I think there are going to be third-party organizations soon.

——More comedians are making videos they like on YouTube, but do you want to try it out?

Ōta: Nope. Too much work (laughs). I’ve tried my hardest to be able to say what I want to say, to begin with. The idea of being able to express what you want on YouTube, even if you’re not well-known, isn’t enough for me. At this point, I’m not interested in platforms where anyone can say anything. If I become unpopular, then it’s the end. And I think that’s fine.

Having no hangups with being lumped into the “comedian” category

——More people look for easy-to-understand means of expression. How do you feel about this?

Ōta: In comedy, accessibility is an asset. Cliché jokes everyone knows are the biggest hits. That’s why I always want my jokes to be easy for everyone to understand, but there’s nothing harder than making something easy to understand. My words are scattered everywhere, even now as I’m talking with you. I want to equip myself with words anyone can understand.

Saying something like “It’s hot today” is easy. But there are many times where I can’t explain concepts. Once I explain what makes a joke funny, then it’s not funny anymore. For example, whenever Tanaka and I are coming up with jokes, I would blurt something that came to mind. It’s usually a little funny the first time around. But by the second time I repeat it, it stops being funny. There are a lot of times where I’m like, “But that was so good just now.” Even after all these years, I still don’t know what causes it. It’s hard to get a grasp on that. Plus, you need to explain jokes [to a certain degree] for the audience to get it. I hope I could learn to express comedy easily.

——Tanaka-san and you continue to make stand-up routines as Bakushō Mondai. Comedians your age are starting to stop coming up with comedy sets, but how long do you want to continue doing Manzai?

Ōta: I’m starting to be unsure. At first, I had a period where I continued to make stand-up routines out of stubbornness. Now, we have a live set every two months, so we need to make a routine. I do think I could’ve quit in the past if I wanted to. Back when we were young, we thought WKenji and the masters of Manzai, Itoshi Koishi, were old but cool. I thought they were good in their own right. We’re approaching their age, so it’s a shame if we were to quit what we’ve been doing. I think I’ll be satisfied doing this at a Yosei (a hall for Rakugo and Manzai) at the end.

——This is a hackneyed question, but what’s your definition of a comedian?

Ōta: The book is titled Geinin Jingo, but I’m not bothered with the category of “comedian” at all. You can call me a TV personality, talent, or comedian. My Manzai isn’t an art form or anything. Things like Rakugo and Kabuki require apprenticeships and have customs; they have a mold, and you need to train for everything. Rakugo and Kabuki are part of the arts. We’ve never been apprentices, as we’re what you would call amateur comedians who learned the craft by watching others. What we’re doing right now is just an extension of that.

If someone says, “Bakushō Mondai aren’t comedians,” then I’d tell them, “Exactly.” I would believe them. If someone says, “What you do isn’t Manzai,” then I could only say they’re right. I don’t need to be called a master of Manzai. That’s just me, though.

——Do Tanaka-san and you talk about the future of Bakushō Mondai?

Ōta: Nah, Tanaka isn’t aiming for anything (laughs). He lives life without thinking too deeply. But isn’t that a good thing?

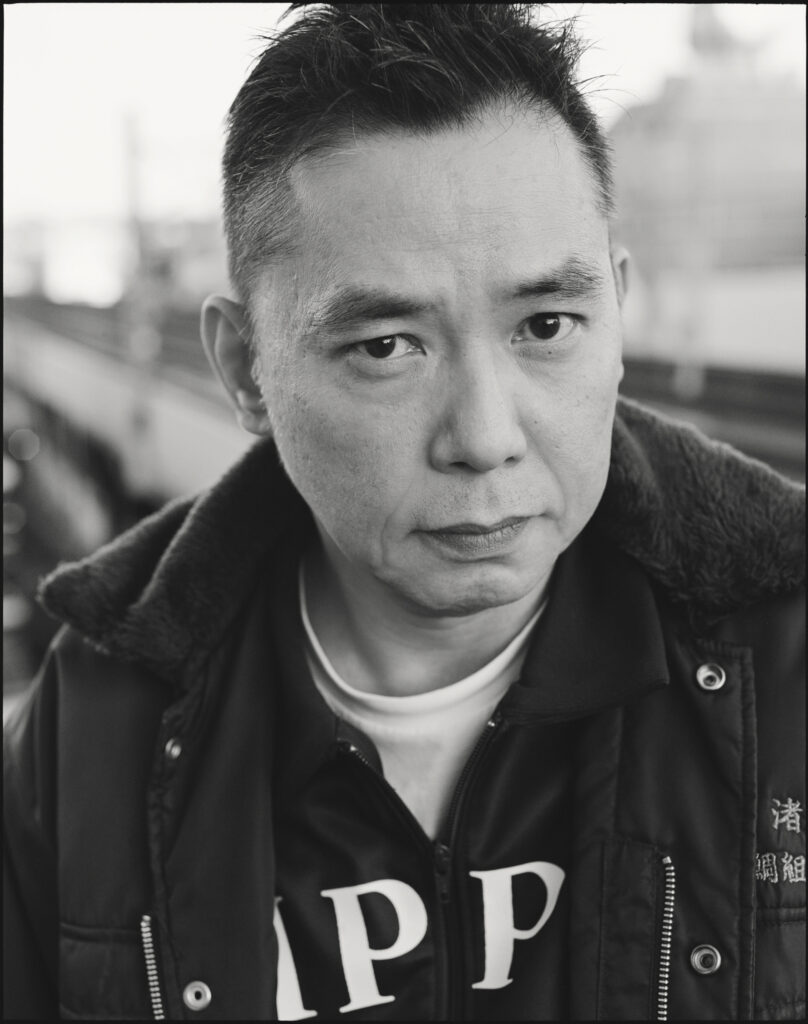

Hikari Ōta

Hikari Ōta was born in Saitama prefecture on May 13th, 1965. After dropping out from the theater program of the Department of the Arts, Nihon University, he formed Bakushō Mondai with Yuji Tanaka, his former classmate in university. In 1993, they won the NHK Newcomer Entertainer award, and in 2006, they won the “Art Encouragement” award from the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. He directed one of the anthology films of The Bastard and the Beautiful World titled Hikari e Wataru, starring Tsuyoshi Kusanagi. Hikari Ōta won the Galaxy award in the Best Radio DJ Personality category in 2020. He is the author of Bakushō Mondai no Nihon Genron (Takarajimasha), Maboroshi no Shima (Shinchosha), Iwakan (Fusosha Publishing), and more. He is also the co-author of Kenpo Kyujo o Sekai Isan ni (Shueisha).

he popular series of essays by Hikari Ōta of Bakushō Mondai, published in Asahi Shimbun’s PR magazine, Ippon no Hon, is now in book form: Geinin Jingo. He writes about a diverse range of topics such as the entertainment industry and drugs, freedom of expression, the masses and television, women leaders and coronavirus, the postwar regime, and prime minister Suga. The book also explores language, crime, the arts, society, and Japan from different angles.

Geinin Jingo

Author: Hikari Ōta

Price: 1,500 yen

Publisher: Asahi Shimbun

Photography Kisshomaru Shimamura

Translation Lena Grace Suda