Izumi Hoshi

Born in Chiba prefecture in 1967, Izumi holds a doctorate in literature and is a professor specializing in Tibetan language and linguistics. Since 1997, she has been working at the Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. While continuing her research in the Tibetan language, she introduces Tibetan literature and films. She wrote and edited the Dictionary of Tibetan Pastoralism. She translated works such as Tales of the Golden Corpse, and Sunlight on the Path, Waiting for Snow by Lhacham Gyal. She co-translated Fantasy Short Stories from Tibet, Here Too Is a Strongly Beating Heart by Döndrub Gyal, The Search by Pema Tseden, A Story about Raising a Pet Dog by Tagbum Gyal, The Valley of Black Foxes by Tsering Döndrub. She is the editor-in-chief of Sernya: Tibetan Literature and Filmmaking.

Izumi Hoshi, a Tibetan researcher and translator, says that Tibetan literary works are very effective in capturing the feelings of people living in the contemporary era. It is often difficult to understand the daily lives of Tibetans because news reports are never sufficient to understand what people are feeling and what they are doing in their daily lives. On the other hand, Tibetan literary works skillfully depict the sentiments of people and many Japanese readers say, “Tibetan stories transcend religious and racial boundaries. We can relate to these stories as they give us clues on how we can deepen compassion, humor, and understanding of others. It’s something Japanese people living in today’s busy world tend to forget.”

Izumi translated several works of Tibetan literature into Japanese, including White Crane lend me your wings: A Tibetan Tale of Love and War, a full-length historical novel by writer and exiled Tibetan doctor Tsewang Yeshe Pemba, and, Sunlight on the Path, Waiting for Snow, a collection of works, published only in Japan, by Lhacham Gyal (aka Lhashamgyal), a leading figure in contemporary Tibetan literature. The short story “Faraway Sakurajima,” set in Japan, and included in Sunlight on the Path, depicts the anguish and struggles of a second-generation Tibetan woman living in exile in Japan who has never set foot on Tibetan soil. In the afterword to the book, Izumi writes, “This work has a powerful message that calls out to lonely young people living in cities for higher education, employment, or migrant work, which is a growing trend in Tibet in recent years.

Lhacham Gyal’s works are introduced as a kind of foreign literature that Japanese people are eager to read these days. However, many Tibetan writers remain unknown, including quite a few female writers and poets. When exposed to different cultures, Tibetan literature demonstrates an intellectual approach that is based on ideas cultivated by the history of persecution and oppression, which are essential for people today living in an era of diversity. We asked Izumi about how Tibetan literature gained the world’s attention and its uniqueness. We also discussed emerging female writers and how Tibetan writers intentionally use Mandarin and Tibetan in their creative process.

On the frontline of creative work, writers carry on the rich oral tradition

–Since the 2010s, Tibetan literature has been translated and published simultaneously in many parts of the world, including Japan. How did this happen?

Izumi Hoshi: Firstly, I’d like to highlight two significant figures in the discussion of contemporary Tibetan literature: Pema Tseden and Tsering Döndrup. This is my assumption, but I believe their engagement with scholars and translators in Japan, France, and the U.S. led to Tibetan literature being translated into different languages around the same time.

Pema was a writer as well as a world-renowned filmmaker. In the late 2000s, he started to work in the film industry, and his work was instantly highly regarded, which led him to work internationally. When I met him at a film festival in 2011, he gave me a copy of his novel. Since it was such an interesting piece, I felt that I wanted to translate it and share it with more people. Initially, I wasn’t planning to translate the book, but Pema contacted me and said, “Someone has started to work on the English translation, and it will be published next year. What about a Japanese translation?” It was my first experience where a writer anticipated a translation from me. I became close enough to him that we would contact each other casually, which led to the translation of his book being published in Japan. I assume the translators, who had received his book at film festivals in France and the U.S., were also drawn to his work and personality. He was the kind of person who brought joy to people around him. When he passed away last May, it was very sad.

The novels of Tsering Döndrup have been translated in New York and Paris. Whenever he releases his latest book, he contacts me. Additionally, he facilitates opportunities for me to meet with Tibetan researchers and translators, whom he knows, in other countries. This has led to expanding my network around him. Whenever I consult with him, he is very cooperative and responds instantly. He shares valuable information about Tibet. Thanks to these two individuals, who have worked behind the scenes with translators all over the world, we saw books of Tibetan literature being published simultaneously.

In addition to that, alongside the accumulated knowledge and translated books from past Tibetan research, it became much easier to communicate in the Tibetan language in the 2010s. This enabled writers to easily share their work with the world.

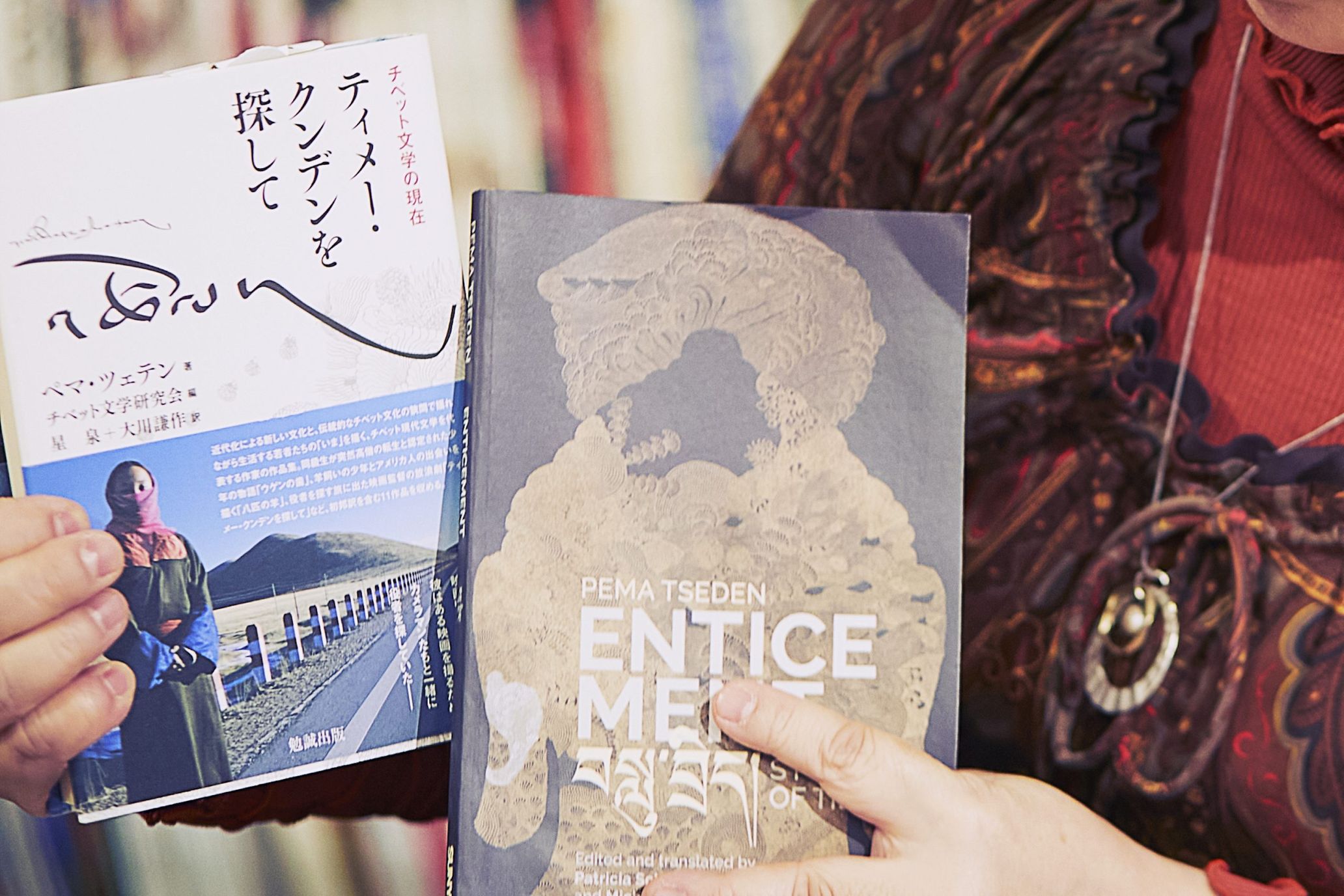

Right: Enticement: Stories of Tibet, an anthology of translated works published in English in New York

–In recent years, it seems that Tibetan literature has been garnering more attention in Japan. What are the characteristics of Tibetan literature?

Izumi: In Tibet, there is a culture that emphasizes storytelling. Tibetan literature was mainly passed down orally, and for the general public, stories were not meant to be read but to be listened to and enjoyed. Because of this background, people highly appreciate storytelling done by individuals using a voice with persuasive words.

I made an online Tibetan-Japanese dictionary with my colleagues called the Dictionary of Tibetan Pastoralism. In this dictionary, there is a term that refers to the nine abilities that men must possess. It lists that men need to be strong, good at swimming, agile, knowledgeable about the history of the land, skilled at telling funny stories and engaging in discussions, knowledgeable and intelligent, patient and brave, and articulate speakers. Five of these abilities are related to speaking. It demonstrates that if a man acquires a deep knowledge of the history of the land and can speak about it, he is considered a fully grown adult.

The Tibetan script is ancient, having been created 1,300 years ago. Due to a long tradition of classical literature being supported by Buddhism, there was no culture of ordinary people reading and writing literature. Instead, they preserved their experiences in their memories by passing them down orally.

Educated in turbulent times, the rare female writers who crafted stories

—One of the fascinating aspects of Tibetan literature, which was introduced in Japan, is the skillful use of proverbs. I hear that proverbs are an integral part of the Tibetan people’s lives, and being able to use them appropriately is a sign of maturity.

Izumi: In Tibet, proverbs are often used in fighting or resolving problems when they arise. In novels, proverbs frequently appear during scenes of conflict. For example, there’s a proverb, “An arrogant dog barks a lot, and an arrogant person speaks a lot.” This is used when you want to assert dominance and defeat your opponent. Essentially, proverbs, which encapsulate truths and outcomes accumulated over time, are used as a basis to justify that what you’re saying is correct. It’s used as a cover to support your point.

Another use of proverbs is as a tool to organize and simplify complex issues that are difficult to understand. When encountering unreasonable events and struggling to comprehend them, it can be overwhelming. In such situations, quoting an old proverb can provide a clue to understanding these events. Proverbs could evoke thoughts such as, “These words have been passed down for many years, so they must hold truth,” or “Similar things happened in the past, so I suppose it’s a common human experience.” This could help people understand the reality that they are facing.

–In Tibetan Women’s Poetry Anthology, which was published in Japan last year, I learned that it has been 40 years since women began publishing contemporary poetry. The book includes poems by seven leading Tibetan female poets born between the 1960s and 1980s. I understand that you consider the works of poets born in the 1960s to be very important.

Izumi: People who were born in the 1960s experienced drastic societal changes during their school days in the late 1970s. Women, who endured the Cultural Revolution in China spanning a decade from 1966, were prohibited from attending school in the 1960s. It wasn’t until 1976 that they were allowed to enroll. However, even then, only a handful of women had the opportunity to attend school, often with the support of their parents. Therefore, anything written by women from this generation is considered extremely precious. For instance, during that time in Tibet, where most Tibetans were engaged in cattle farming and agriculture, parents needed to pass down household skills to their children for survival. Mothers had to train their daughters in household chores so that their families thrived as cattle farmers and survived in the village. To ensure they didn’t miss out on this training, girls were not permitted to attend school.

Moreover, people believed that nothing good would come of it if a girl attended school. Dekyi Dolma, a poet born in 1967, caused a stir in her village when she expressed her desire to attend school. Rumors began to circulate that she might be possessed by a goblin for wanting an education, greatly saddening her. Her father took pity on her as she was determined not to abandon her aspirations. He escorted her to a boarding school on horseback and she could eventually go to school. The girls from this generation had to endure tremendous hardship and make extraordinary efforts to pursue an education.

In terms of creative writing, writers born in the 1960s, both men and women, faced numerous challenges due to the lack of predecessors who composed poems and stories in Tibetan. This was primarily because Tibetan was fundamentally a language for religious purposes and not for expressing the emotions of lay people.

–What was it like to write in Mandarin under circumstances that made it difficult to write in Tibetan?

Izumi: Although they are few in numbers, there are Tibetan women, who received education in Mandarin in the 1960s and 70s, attended secondary schools to universities, and were exposed to Chinese and foreign literature just like men.

In those days, one thing to note is that children of high-ranking officials were given priority to receive school education with the expectation that they would become bureaucrats. Both girls and boys could go to school, which led to Tibetan students enrolling in Beijing University. Among them was a female student who loved storytelling. After graduation, she wrote a novel in Mandarin. At universities in China, they teach the basics of classical Chinese, which probably helped her write a novel. With many predecessors having written novels in Mandarin, it must have inspired her that she could also do the same.

Storytellers thriving between different cultures

–I have heard that there are many full-length novels in Tibetan literature written in Mandarin. What are the reasons Tibetan writers use both Tibetan and Mandarin?

Izumi: Firstly, most Tibetans are bilingual in Tibetan and Mandarin. They cannot survive without using Mandarin, and there are no schools that solely teach Tibetan. Nowadays, thanks to television and the internet, it’s much easier to learn a language. However, Tibetan people were already bilingual before these advancements. Regarding reading and writing, it depends on the type of education you received.

When we look at the writers, some write only in Mandarin or only in Tibetan, and some write in both languages. Those who write in Mandarin typically attended Mandarin secondary schools in China, even though they might have grown up with their parents speaking Tibetan when they were young. In such cases, it was likely that they didn’t have opportunities to learn Tibetan, unless their parents made a concerted effort to teach them. Consequently, they might proceed to university without knowing how to read and write Tibetan. However, their identity remains Tibetan, and they write stories and poems about Tibet in Mandarin.

While this is not a common instance, most writers, who write in Tibetan, went to local schools for Tibetan, located in each prefecture, which teaches Tibetan. They received higher education in Tibetan, enrolled in the Tibetan course at the local university for ethnic minorities, and became writers. The writers who write in Mandarin and Tibetan are Pema Tseden and Tsering Döndrup, whom I have already mentioned. They also do translation between these two languages.

–Even if they are born in the same place, it seems that not only the language but also the knowledge varies greatly depending on the educational paths they chose.

Izumi: The input would be different depending on whether you are educated in Mandarin or Tibetan at a Tibetan school. Especially the exposure to classical works is totally different. The study of the classics creates the groundwork for a person’s education. Even if you grow up in the same location, learning reading and writing through the language education provided by your parents would lead to learning completely different types of expressions.

Pema, whom I have mentioned, attended a Tibetan school but wrote his first novel in Mandarin. This work was published in a literature magazine in Mandarin in the Tibetan Autonomous Region in Lhasa. After receiving high praise, he began to write in Tibetan. However, once he started shooting films in Tibetan, he returned to writing his novels in Mandarin to reach a wider readership among Mandarin speakers.

–Why did some writers insist on writing in Mandarin?

Izumi: Writing in Mandarin would lead to an increase in readership. Due to the educational environment, many Tibetans can only read and write in Mandarin. By writing in Mandarin, writers can reach these readers. Additionally, Tibetans tend to perceive stories as something to be listened to rather than read with their own eyes. I’ve heard that there are radio programs that read novels. During the extended lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic, many readings were uploaded on the internet, and a lot of people listened to a wide range of Tibetan classics and contemporary literature. Writers contemplate how to use Tibetan and Mandarin when writing a novel, while readers can choose whether to read or listen to the story. This is the current situation in Tibet.

As a culture that cherishes storytelling in literature, Japan also has similar traditions when it comes to reading classics, such as rakugo. I believe Tibetans enjoy literature in a manner similar to how the Japanese enjoy rakugo. I am considering whether I should adopt the Tibetan way and begin reciting Tibetan literature translated into Japanese.

—In the novel White Crane lend me your wings: A Tibetan Tale of Love and War, which was originally written in English, the term “green-brained” is used in the story. While in English it means environmentally conscious, in Tibetan, it is used to denote ideological corruption or backwardness based on what those two words mean in Tibetan. I understand that you translate a mixed language and words created by writers while also taking into account the conversion between Tibetan and English.

Izumi: Not limited to White Crane, Tibetan writers use parentheses for emphasis and also incorporate Tibetan words that were derived from English or English words influenced by Tibetan. They also treat Tibetans similarly to the English language, freely adopting various linguistic methods. We refer to this as the deterritorialization of languages. It’s not about the Tibetan language being overtaken by the dominant English language, but rather a way of expressing that Tibetan exists within the dominant language.

For example, similar language adaptations are observed in Singaporean English and Indian English when spoken. It demonstrates how a minor language can influence a dominant language. Therefore, even though the book is clearly authored by a Tibetan writer, it contains many expressions that would never be found in the writing of someone who only speaks English.

2. Tashi Delek is the only Tibetan food restaurant in Tokyo’s 23 wards. Lobsang Yeshi, the restaurant owner, and Izumi Hoshi.

ーーI learned that there is a plan to publish a full-length novel by a Tibetan woman writer for the first time in Japan soon.

Izumi: In April, a long-form novel titled Flowers and Dreams by Tsering Yangkyi, a female writer, will be published. It tells the story of a sisterhood among four prostitutes working in a nightclub, living together in a small apartment. Despite their traumatic pasts and the sorrowful destiny that awaits them, the novel is written with a warm, protective gaze. Their dialogue is lively, making it feel as if they are right beside you. The novel will be published by Shunjusha Publishing Company as part of the new series Asian Literature Library. I hope readers look forward to it.