In 2020, TEMPURA, a magazine about Japanese social issues and underground culture, released its first issue in France. Many media introducing Japanese culture overseas already exist, but most of them only handle traditional culture and Japanese artists; in that respect, TEMPURA covers topics such as the Japanese working environment and women’s issues in society, as well as unique Japanese perspectives towards family, sex, death, and more. Compared to similar magazines, TEMPURA stands out as one of a kind, attracting more and more attention not only in France but also in Japan. For this article, we interviewed Emil Pacha Valencia, the Editor-in-Chief of TEMPURA, about the reasons behind the start of the magazine, his original editorial perspective, and his perception of Japanese culture.

Tempura, the Japanese diverse dish, originates TEMPURA, the magazine

――What made you decide to start publishing TEMPURA?

Emil Pacha Valencia: Many French people like Japanese fashion, food, and art, which are mainly represented by “kawaii” or pop culture. However, Japan actually has an extensively diverse background in youth culture, contemporary and even subculture. For French people who have a one-sided image of Japan, and for creators such as fashion designers, photographers, and architects, the new movements and cultures happening in Japan are stimulating, and in my opinion, will lead to inspiration for awareness and creation.

――What’s the reason behind calling your magazine “TEMPURA?”

Emil: When I read Roland Barthes’s philosophical book L’Empire des signes, I found a very poetic description of the tempura. Later on, when I looked into the history of tempura, I found out that it originally came from Portugal in the 16th century, and it was called “tempora.” It’s a dish packed with different ideas and cultures from multiple countries. After a long history of foreign influences, the Japanese uniquely re-interpreted the dish, turning it into a symbol of their own culture, which later spread all over the world. I felt that it represents how ideas, people and cultures have always been circulating, influencing each-other, despite the borders we tend to build. I thought that the story behind tempura as it is would become a symbol for the magazine.

――How was the response in Paris after releasing the fourth volume?

Emil: At first, it felt like kind of a gamble, but we believed in the concept, and it gained popularity. I don’t really know because I haven’t heard anything negative directly, but it seems that people see TEMPURA as a medium to learn about radical ideas and Japan’s diverse cultures, something different from the other magazines about Japan, which only focus on traditional Japanese culture, manga, and anime. We’ve received positive opinions from the French and Japanese embassies, and journalists. We’re currently producing volume five.

I was mostly worried about what our readers from Japan would think of the magazine: at the end of the day, we’ve received positive feedback, which might be connected to the fact that TEMPURA deals with social issues in Japan. I had the impression that the Japanese media at the time did not actively discuss women’s or minority-related issues. TEMPURA does not take a critical approach to the matter but rather aims to convey Japan’s “present” truth as an opportunity for open conversation.

A flat, taboo-less view of Japan’s social issues and subcultures

――Why did you decide to write about Japanese social issues?

Emil: It’s because TEMPURA expresses itself unbound by taboos of any kind; I don’t intend to only focus on social issues. First of all, conversation is essential. For example, when dealing with the topic of the working environment of Japanese women, we questioned our situation in France by looking at what’s happening in Japan. Articles covered by Japanese journalists and activists serve as an objective reflection of society for French people as well. Rather than dealing with a specific social issue, I felt that a bird’s-eye view of such problems that includes both positive and negative opinions would better lead to a global conversation.

――Now that you’re delving deeper into Japanese culture, is there anything that re-captured your interest, or conversely, that you can’t understand?

Emil: Actually, it’s full of things I can’t understand. The ultimate goal is to delve into what you don’t understand. Even if you understand one layer of Japanese culture, there’s always a new, deeper one underneath. Every time I read a contribution from a journalist, I learn, I ask myself new questions, and new thoughts come up.

On the other hand, it’s also a challenge for me. I’m neither Japanese nor raised in Japan. I learned about Japanese history and language, but there are many problems that I cannot understand due to different backgrounds. Is it because I’m French? TEMPURA’s purpose is to pursue such premises and backgrounds.

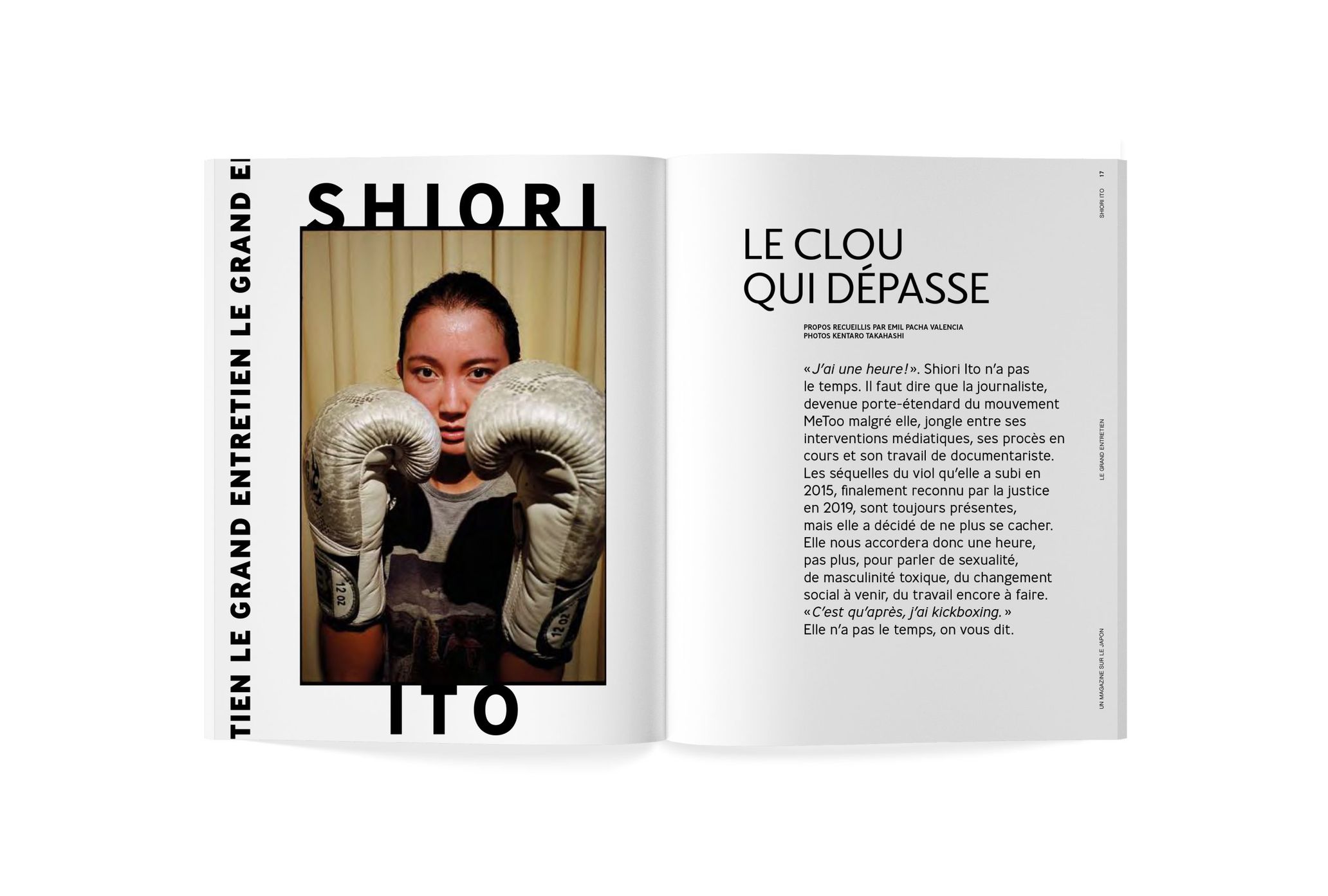

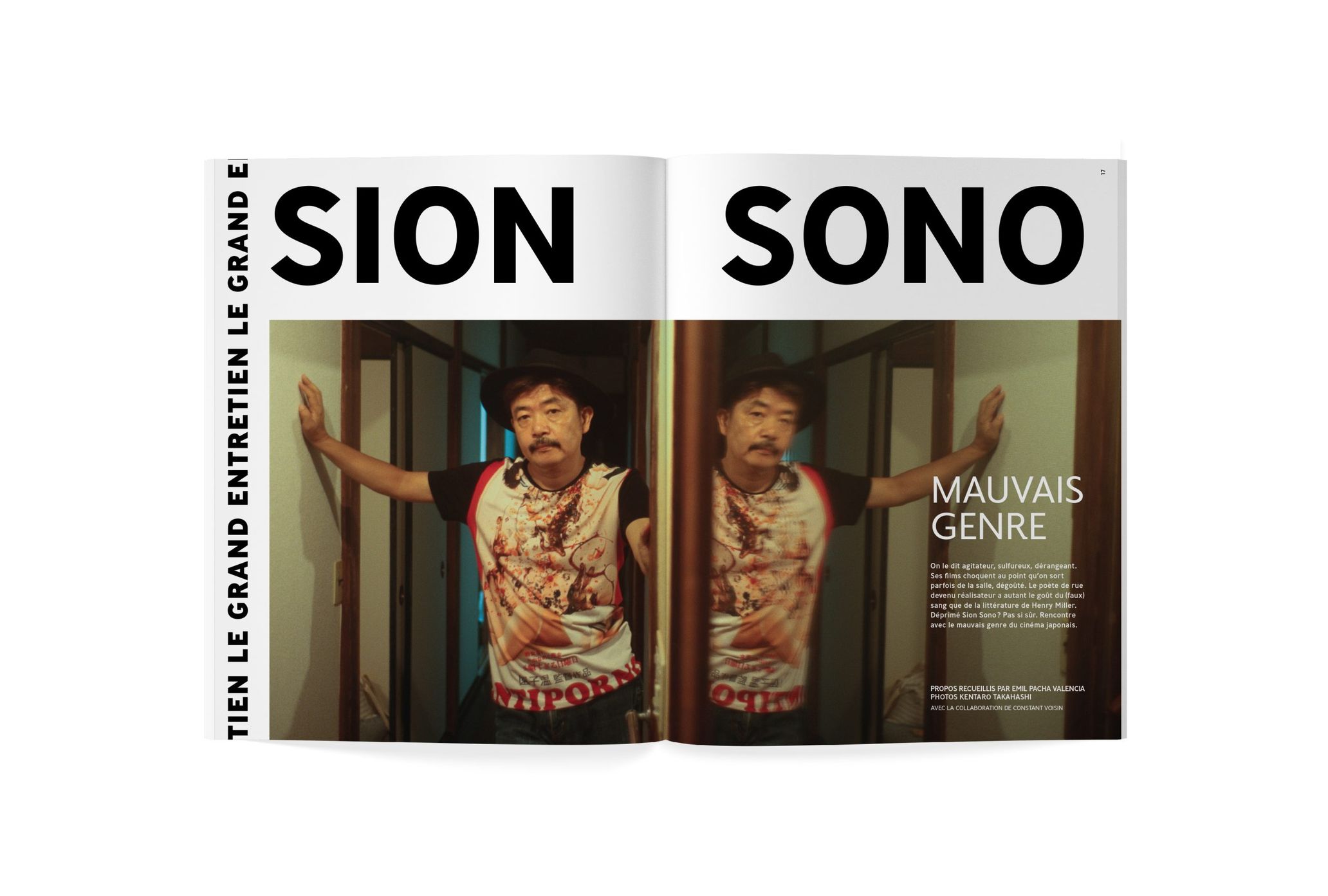

――I find the topics and people you cover for TEMPURA very interesting: for example, Shiori Itō wearing boxing gloves and Chim↑Pom’s Ellie being pregnant on camera, or director Sion Sono. What kind of thought process is at the base of your editorial and selection of subjects?

Emil: Rather than covering world-famous Japanese celebrities, I prefer to showcase people who are expressing disruptive points of view. In Japan, all sorts of people and movements are coming up, and I want to keep finding the right individuals to symbolize this new conversation. The voices of people like Ito-san, Ellie-san, and Sono-san are getting louder, especially overseas, and I believe that everyone around the world should listen to such voices. French people have a stereotypical image of Japan, one of peace and quiet, and I want to change that. There are many challenging and radical cultures in Japan. Also, I think Mieko Kawakami single-handedly changed Japanese literature. Even on a global scale, I’d say she’s probably one of the best writers right now.

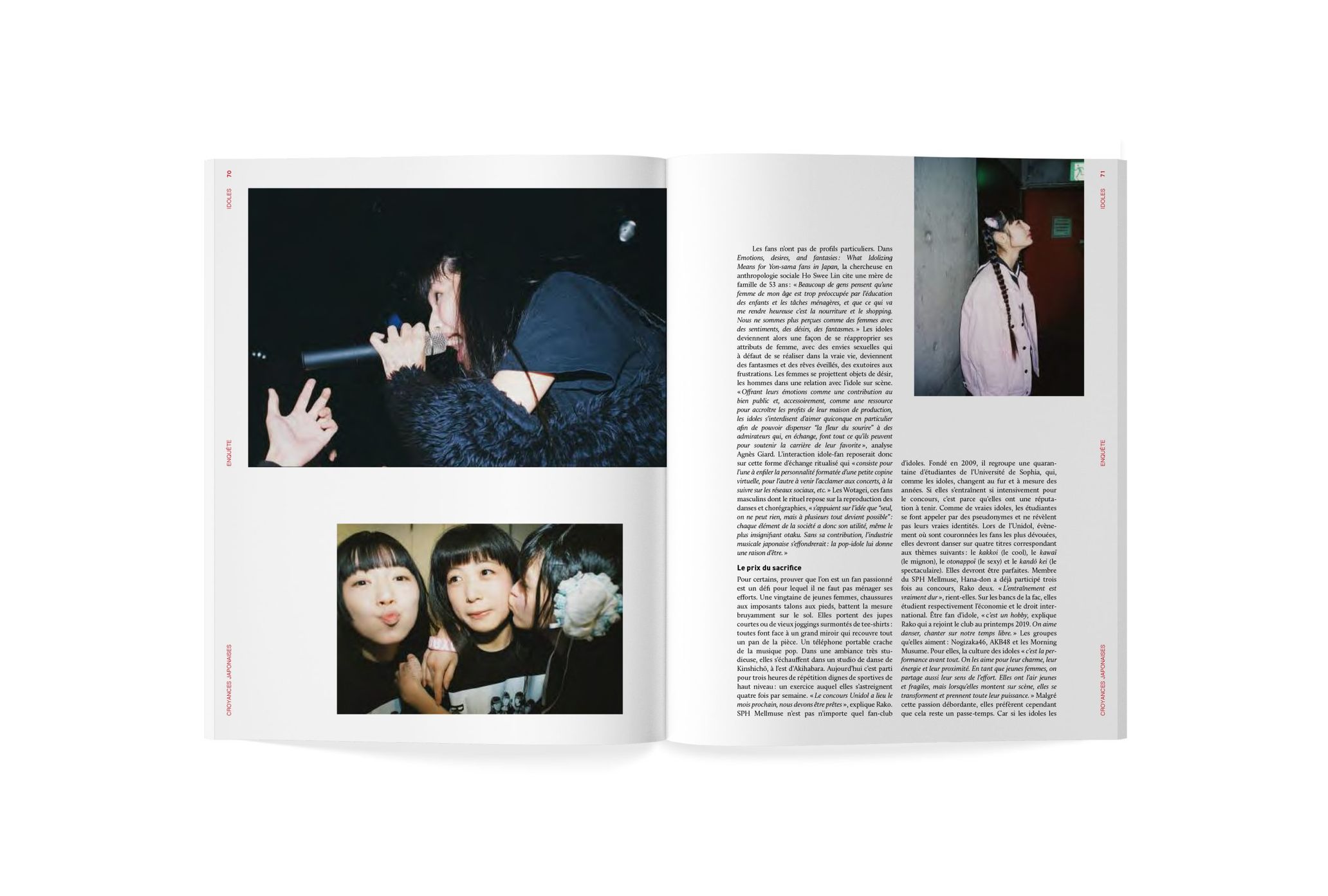

――Your magazine covers many different sides of Japan’s distinctive underground culture, such as traditional tattoos, Kinbaku, or photographer Zaza Bertrand’s Japanese Whispers series, for which she took pictures of different love hotels. Why are you interested in such topics?

Emil: Underground cultures and subcultures are all parts of a larger cultural environment; such cultures are indispensable for expressing the diversity and complexity of Japanese culture. TEMPURA also has a special section dedicated to subculture. All cultures are talked about through history and are in constant change. For example, in the American continent, tattoos used to be a ritual of prisoners or sailors in the past but now are understood as mainstream fashion. It is common to all sorts of places that what used to be considered sub-stream becomes mainstream.

A Japanese hippie’s lifestyle at a homestay completely changed my image of Japan

――What made you crazy about Japanese culture?

Emil: When I was three years old, I lived in Cuba before my family returned to France: my neighbor there was a Japanese fisherman, and our families were close; my cousin married his daughter and moved to Japan, where he opened a Cuban restaurant called “Bodeguita” in Shimokitazawa, Tokyo. When I was fifteen, I went to visit them in Japan and experienced culture shock. The place I stayed at for my homestay was a 200 hundred years old Japanese-style house situated in Setagaya, and I found myself attracted by its traditional Japanese garden and its architectural structure, the fact that it had tatami mats and roof beams, and so on. From there, I got more and more into Japan. However, the landlord was the exact opposite of what the house looked like: he was a long-haired hippie, the kind of person who keeps birds and monkeys in his garden. At that time, I realized that Japan was a diverse country, far from the stereotypical image that foreigners, including myself, had. Either way, it was impressive.

――What sort of social issues or cultures are you particularly interested in?

Emil: Right now, I’m interested in social issues concerning women’s rights in Japan. Many female activists have begun to speak up, and I think more and more women will play a leading role in changing the future of Japan. I am also excited to see how the gender gap problem, which is still big in Japan, will change in the future. Then I’m always interested in Japanese photography: I’ve always loved photography, and TEMPURA mainly features young Japanese photographers.

Photographers worthy of attention and Tokyo’s recommended locations

――Are there any Japanese photographers who particularly caught your attention?

Emil: He’s not with us anymore, but I love Masahisa Fukase. He may not be as known as Araki or Moriyama, but he brought various innovative photographic techniques to the world. He was able to express himself outside the boundaries of photography as a medium. Another one, closer to us would be Motoyuki Daifu; his series Still Life is incredible. His photographs are colorful and graphical; his style seems cluttered, animated, but at the same time, delicate. Photographers tend to sell stories with their pictures, but his work shows reality, which I see as far more powerful, beautiful, and full of imagination. This applies to artists as well, not just photographers.

――What are your favorite spots or shops in Japan?

Emil: One of them would be “FEETS,” a specialty shop in Yūtenji. The genre of selected brands is wide, and the staff is well informed on the products. The shop offers original eyewear as well as many Japanese designers’ selected items for men, which scene I find particularly interesting in Japan. Another good spot is “Switch Coffee Tokyo” in Meguro; the owner is what you may call a coffee geek. The roasting is perfect, and I find the coffee delicious, even from a global perspective. My last recommendation would be “Kyō,” a set meal restaurant in Musashi-Koyama: this is my secret place. It may be difficult to find since it’s in the back of a narrow alley. The building is old, and an old couple runs it. The grilled mackerel and sablefish, even the pickles are excellent, yet cheap. It’s very Taishō era-like. I’ve been going there for about ten years, and it feels like a second home.

――Traveling is difficult due to the pandemic; has it been hard to work with Japan under such circumstances?

Emil: It has been. I used to participate in interviews, but now it’s not possible. Most of the journalists who contribute to TEMPURA live in Japan, so we hold countless online meetings to interview and exchange information. As soon as this situation is resolved, I’m planning to set up an office in Japan and work from two bases.

――In regard to TEMPURA, what is your plan for the future?

Emil: I would like to create an English format and expand the market to the world, centering on New York, Los Angeles, Canada, etcetera. Of course, I’m aiming for a trilingual publication, including Japanese. Actually, we were going to collaborate on a Japanese electronic music event in Paris last year, but it was postponed indefinitely because of the virus. As soon as the pandemic ends, I’d like to start a new project and actively hold physical events. This will be a year full of challenges; distributing the magazine will be challenging too. I’d also be happy to collaborate with TOKION. It’s interesting to delve into new movements, but also to re-edit pre-existing cultures from a new perspective like TOKION does, which has something in common with TEMPURA’s statement. This year, I want to meet as many people and discover as many media as possible.

Emil Pacha Valencia

Based in Paris, Emil is the Editor-in-Chief of TEMPURA Magazine. In 2019, he started the publication of TEMPURA, a magazine that focuses on Japanese social issues, underground culture and subculture. The project was crowdfunded and achieved 300% of the target amount at the time. The fourth volume recently came out, and a fifth is underway.

Translation Leandro Di Rosa