To see, look, watch, examine, oversee, look after someone; why, what, and how do we use our eyes? A photograph is born from the relationship between seeing and being seen. It documents the things a photographer sees and is an object for the viewer to look at. A show questioning how people accept exhibitions as spaces reserved for the act of looking was open until recently. The serial exhibition, titled error CS0246, explored the contradictory relationship between exhibiting and preserving something and had a “no entry” policy. We spoke to the curator, Kakeru Okada, and photographer Hiroko Komatsu about it.

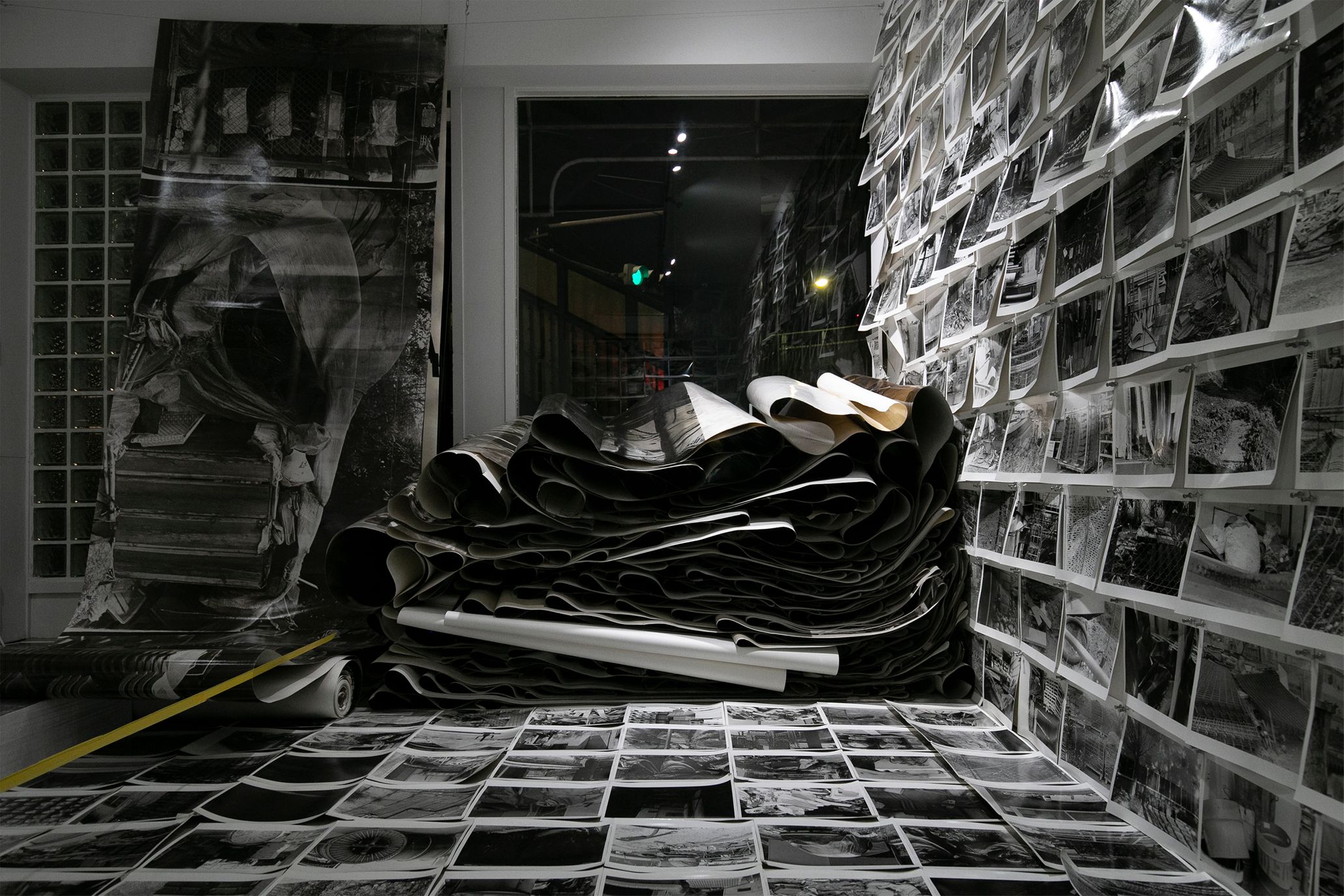

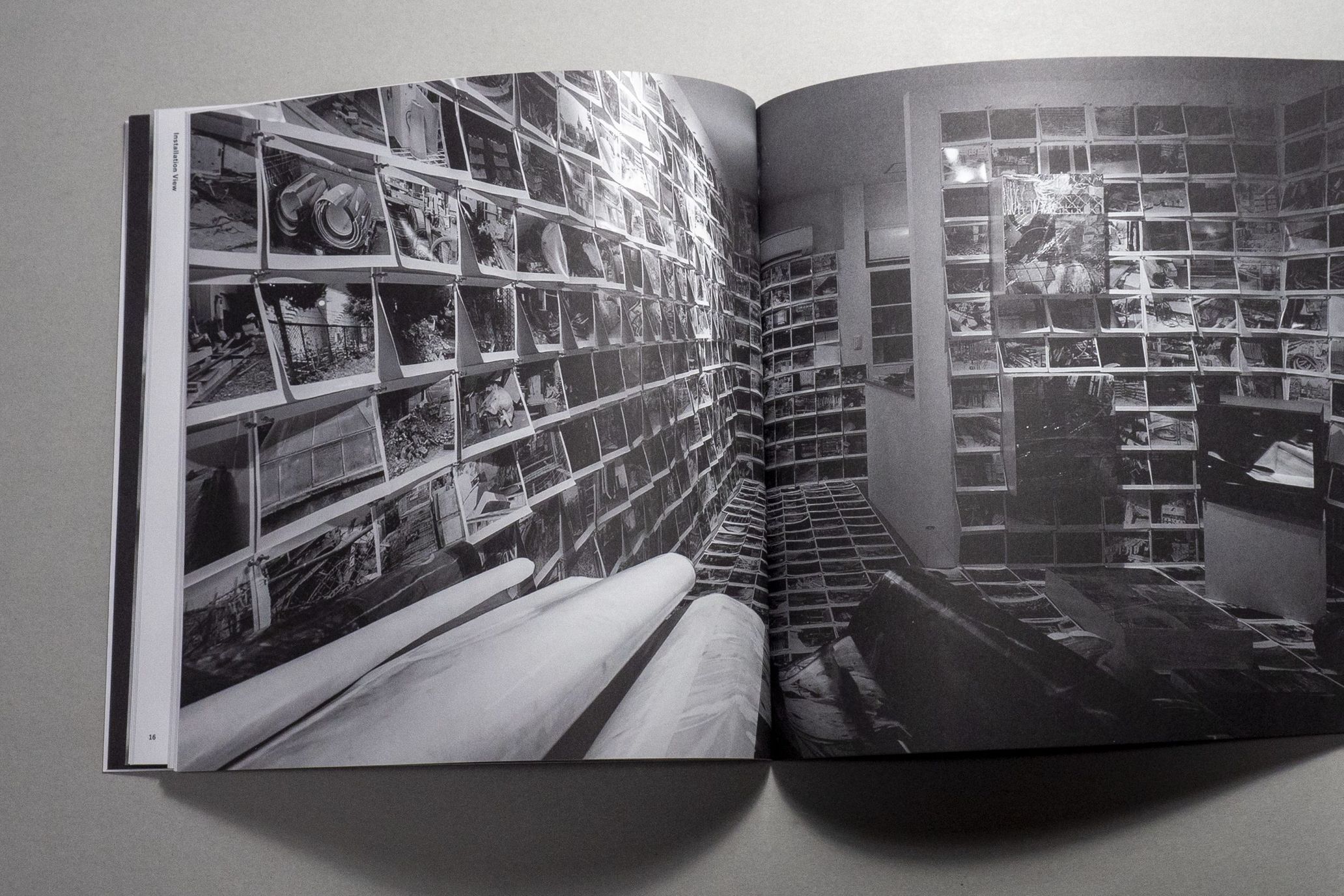

Rolls of photographic paper (110cm in width, 30m, and 20m in length) folded and piled on top of each other. The weight of the top layers crushes the lower layers. Photographic papers hanging from the ceiling block the entrance, and over 600 20cm by 25cm photographic papers cover the floor and walls. There are styrofoam and photographic paper wrapped in wrapping paper on the floor. A camera in the corner takes a photo of the space once an hour. It continues to take pictures for 24 hours. The intense, photo-bombarded space hinders the viewer from looking at the images. It makes the viewer feel anxious, as the experience is akin to being watched by someone.

Accepting restrictions, exhibition spaces as “fascist architecture”

—People have traditionally viewed exhibitions as spaces for people to enjoy art. How did you come up with the no-entry restriction for error CS0246?

Kakeru Okada (Okada): The phrase “error CS0246” is an error code that pops up when you’re programming. This error code shows up whenever you’re building a virtual space via development platforms like Unity and haven’t decided on the name of your virtual space yet. I felt like the uncertainty of the future related to that. That’s why I used it as the title.

Limited visitors, social distancing, reduced business hours, regular ventilation — this is the state of the world today, one we can’t ignore. When I thought about opening an exhibition by considering such restrictions, I realized we could create it outside the actual venue by prohibiting visitors from entering since most of the limitations apply to the indoors.

Photographer-and-artist Hiroko Komatsu has been questioning the narratives behind museums and exhibitions. Inverting these things is at the root of what she does. She thought it was more logical to hold an exhibition that doesn’t let people in because we were going to cover the floor and walls with photos.

Hiroko Komatsu (Komatsu): If the inside doesn’t exist, then the outside doesn’t exist and vice versa. Even with photos, there’s the front and the back. No matter how we display pictures, there will always be two sides. In the sense that photo exhibitions work as long as there are photos in them, we could treat venues as objects. You could even say it’s one form of fascist architecture, as it doesn’t require people to be there. Yes, I created an inside space where people could technically go in, but I can’t help that they have bodyweight and the earth has gravity, which would cause them to step on the photos, inevitably. I thought, “If people are going to think I’m being rebellious by putting the focus on visitors stepping on the photos on the floor, then why not let them see the work from outside?”

Okada: She questions narratives with the artists, audience, and art institutions in mind. Komatsu-san set up an indoor space covered with photos, but her aim was never to make people step on them. At first glance, it might seem like she’s contradicting herself, but it relates to the exhibition itself.

What has photography been until now? Documenting absence and the surfacing of materiality

—Komatsu-san, you use a lot of space as a motif, such as storage spaces for materials. Even with this exhibition, the photos aren’t the only works on display, as the venue itself is a piece of work. What do you think is the relationship between the act of seeing through taking photos, objects, and space?

Komatsu: There’s no central focus in this exhibition space. We designed it in a way that makes the viewer not know where to look. The sequence of similar-looking photos isn’t in chronological order, which makes the viewer constantly feel like they’ve seen it before. Because they can’t settle their eyes on one thing, their line of sight gets sucked into the following photo at once. It’s like something in between still images and moving images. Videos move linearly and chronologically. But with this exhibition, the onlooker is looking at a surface, so they can’t escape anywhere, and the direction is never clear either. I don’t take pictures of the sky or ground — things that make people think of spaciousness — so a part of me intentionally wants to disorient people.

Regarding whether I shoot objects or space, even if I photograph an object, I’m also isolating a particular space by framing it. So, you can’t separate objects and space. I shoot both and neither at the same time. When I take photos, I use a map as guidance and look for industrial areas that I’ve never been to before. These places are usually barren and deserted. The gray landscape unique to industrial areas makes me feel at home. I’ve only seen Mono-ha (an art movement born in the mid-60s, which used both natural and unnatural materials as a reaction against industrialization) installations through photos. But I sometimes come across objects that resemble Mono-ha whenever I shoot industrial areas.

Okada: People often say the quantity of materials Komatsu-san uses is a trait of her work. I also think the lack of objects is another trait of her photography. With Mono-ha’s photography, objects are artworks, and images of said objects document and prove that. Meanwhile, with Komatsu-san’s photography, the storage spaces for materials can be considered art, but so-called artworks or individual objects aren’t the subjects. Meaning objects [as the subject] are absent in her images.

—Even though Komatsu-san’s exhibition lacks objects, the photos have a palpable sense of materiality. Why is that?

Okada: For instance, people studied films in the 20th century by sitting in a dark room and watching a screen. But thanks to the spread of liquid-crystal displays, people could then watch videos anywhere. For the first time, people questioned why they used to sit in a dark theater for two hours. People challenged the medium itself. Similarly, the word photography applies to both old and new media and iPhones and analog cameras. Because of modern technologies like the iPhone, we finally understand what Komatsu-san has been shooting and how we understood photography until this point. I think you can say the word materiality surfaced in your mind as one characteristic of old media.

Komatsu: Photos are both images and materials. People use a particular type of paper that’s thick, prone to curl into itself, and difficult to handle to keep the photos close to what they imagine. They use glass and a matte finish to make the photos flat and frame them for their exhibition. In a way, this method is more blasphemous towards photography, and what I do might be a liberation of photography.

Feeling liberated from unexpected errors and self-consciousness a la labor and working on tasks

—Amid the emergence of new forms in photography, I get the impression that you place importance on formats, specified sizes in industrial goods, and units. This can be seen in how you use the Leica M3, 35mm monochromatic film, and 20m or 30m rolls without cutting them. Could you talk about why you’re particular about these formats while keeping your attitude towards overarching narratives?

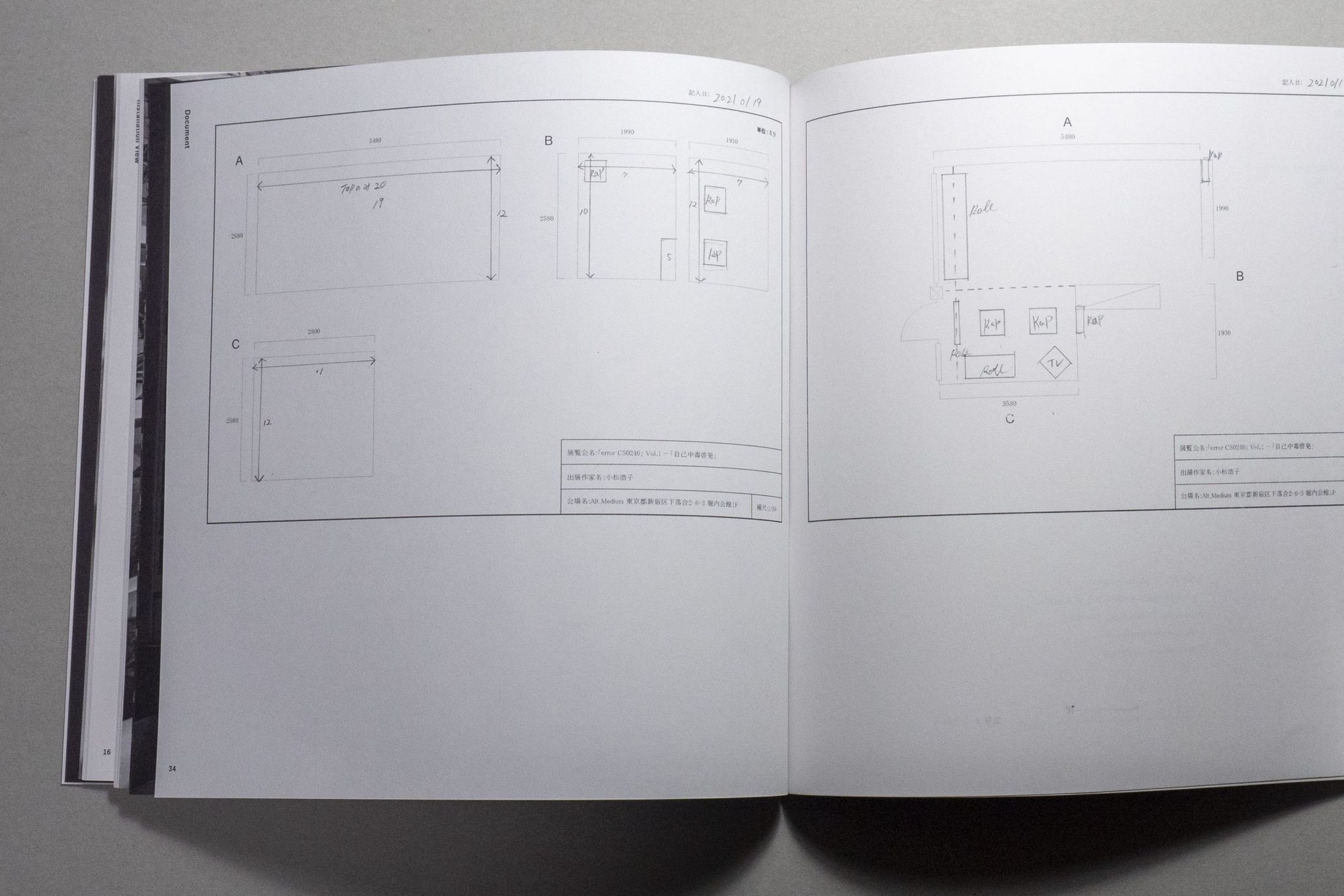

Komatsu: Photographs are industrial goods that have specified sizes, and they exist as a foundation. The thickness of the wires and the shape of pushpins you use for exhibitions all have set measurements. I choose the materials I use according to necessary criteria, such as how easy something is to handle and its price. The storage spaces for materials in my photos could be seen as a base that supports a society where sizes are specified. If everything has no limitations, then I can’t assemble anything. A gallery’s walls, size, and structure can’t change shape according to my exhibition setup, right? I can come up with ideas from the set measurements of printing paper and the fact that exhibition spaces can’t move. This is a very freeing thing. I could go to a venue and be like, “Their tacks are like this, so I could do this and that.” If there’s not enough space on the walls, I could put things on the floor. I could also hang the work on a wire.

I calculate the number of photos I need to take and show according to the specifications of a venue. I usually shoot once a week and shoot on over ten rolls of film whenever I can. I print out 100 photos per week. Because I turned this process and everything into a task, it wears me out a lot. That leaves no space for potential fetishization or excessive self-consciousness. It also increases my chances of making mistakes, and that way, I’m able to incorporate errors into my work. I use my entire body, so I channel what I shoot into photos and exhibitions. I think they influence one another.

Okada: If Komatsu-san creates her own format, the viewer could no longer tell how she’s taking a new approach. By using a specified size apt for repetition, such as 89mm by 127mm printing paper or 194mm by 244mm printing paper, you can focus on the side people have overlooked in photography. It’s not a stretch to say she creates errors that open up new fields and the possibilities of photography by using her works as a foundation and laboring on tasks.

Exhibition and books — expanding the medium of art

—Okada-san, aside from planning and curating exhibitions, you also established your own publishing company, Paper Company. Komatsu-san, you also make photo books independently. What do you think about making exhibition spaces and books? What are your thoughts on the relationship between exhibiting and preserving art, which is also the theme of error CS0246?

Komatsu: To begin with, regardless of whether an object is alive or dead, it gradually deteriorates. It eventually decays (ages) and stops functioning (dies). In the end, it disappears. One goal of photography is for museums and public institutions to purchase and collect them. People think chemically treating photos and trying to preserve them eternally are imperative, but is it possible? I feel weird about people saying they can’t preserve the photos on the floor of my exhibition. The rolls of photos are piled on top of one another, and it’s the most damaging way to keep them. It’s the worst condition for preserving them (laughs). Photo books are objects too, but it’s one way to show one’s work. Photo exhibitions and photo books are vastly different things. Including the texture and the act of flipping a page, books are their own format. If a book has many people involved, like a designer and editor, then the designer plays a significant role in being in charge. I think it has an ensemble-like quality to it.

Okada: When you think about the state of preservation in Japan, we barely have institutions that could preserve photos by using chemicals. On top of that, most of the budget of museums goes to administrative costs. Even big museums lack storage units and have stopped collecting photography because they can’t manage the administrative costs. They’re starting to archive photos digitally. Until now, looking at art within exhibition spaces was the most vital thing, and people treated books as mere reports on exhibitions. But I think there’s more to it than documenting an exhibition in a book. There are things you could only do by making a book. Regardless of coronavirus, as long as we equate not going to an exhibition with not seeing it, then we’d be saying the work of artists, who have no choice but to rely on the internet, doesn’t exist; especially in Japan, where East Asia has fewer museums compared to the rest of the world. I believe by making books that aren’t just exhibition reports, such as an exhibition you can “read” or an exhibition in a different form, we can showcase domestic exhibitions to the world.

—I want to get deeper into the matter of diverse forms of exhibitions. In your books, you credit the people who installed the artworks. Could you talk about why you place importance on those who install the work when you curate shows?

Okada: No matter how good your materials or blueprints are, you can’t build a house without builders, right? You can’t have an exhibition unless someone physically puts it together. Concerning actualizing exhibitions, installers should be the most important people. Compared to other countries, where different institutions properly support curators, artists, installers, and those who handle chemical properties, people tend to treat artists as the most important ones in Japan. Installers are at the bottom of the hierarchy, and most of the time, curators leave that part up to a third-party company.

Photography and moving images have developed alongside technology, so we shouldn’t understand that field in a manual-like manner. We need to understand what cameras shoot on a more detailed, constructive scale. Or else we risk losing sight of the work and the artists’ intent. Within the field of video media, which operates on the assumption that other people will experience it, you might understand the artist or their work based on literature. But I think it’s impossible to curate video media solely based on research. I want to value the role installers play, to understand the artist’s intent and what they’re saying.

Komatsu: I think there are many reasons for this, such as the difference in budget or having various tasks to work on, but in Japan, many curators can write essays but won’t come down to the venue to help. Curators that can do everything like coming up with a plan, constructing, and publishing are rare. While the exhibition is ongoing, the rolled-up printing paper keeps on being crushed by its weight, and the humidity causes the plywood on the floor and walls to curl, which causes the pushpins to fall; the inside continues to change. Okada-san came up with the idea to document the space by taking one photo each hour from a fixed point. I feel like he’s the type of curator who could assign new values to art, values the artist hadn’t intended.

Look, see, watch- Why and what do we see? Investigating the meaning of the exhibition

—Conventionally, people have accepted exhibitions as things people see. With error CS0246, the audience is an added value, not an absolute necessity. How do you think shows and the experience of enjoying art are going to change in the future?

Komatsu: It was already changing slowly before coronavirus. People ask themselves, “Are we really, truly looking at something?” What’s vital isn’t the number of visitors. My work can be understood as something that’s directed towards and raises questions against the current system of Japanese museums. What visitors feel and how that connects to their life and society at large — I think these things will be more crucial.

Okada: This is more about cognitive science, but it’s about whether the act of looking, seeing, and watching is passive or active. In recent years, how the audience understands these things have been changing. Moreover, because of coronavirus, going to exhibitions has become a life-risking act, to put it extremely. Thinking about why we go to exhibitions has become a prerequisite. Art that exists for art’s sake, photography that exists for photography’s sake. Many people can’t commit to art, and they see it as an inside joke. I think it’s about time we change how we view exhibitions and art as a means of self-expression, something artists must take on by themselves, and how viewers can go to gallery exhibitions for free and without risking anything. Exhibitions can change the state of society and the way we think; they’re beneficial for society. I have no desire to advocate for edgy or novel art, but I think about how artists can effectively connect their work to society. I think about how to rebuild this system, which lacks in functionalities of exhibition spaces and so on. I believe we can still create more books, events, new experiences, and shapes of art.

Photographer Hiroko Komatsu’s words, “People don’t have to see it,” made me think. I went into the interview under the assumption that photos were something to be seen. The 600 pictures and rolls of printing paper overwhelmed me. I could barely make out fragments of landscape photos being crushed by its weight. The more I tried to see, the less I could, and my knees felt weak. Simultaneously, I pictured thousands of images I subconsciously take in every day, which made me feel dizzy. By creating a space where people can’t see, she makes people ponder on the act of seeing itself. error CS0246 incorporates errors in a society where the future is still unclear, and it reveals the meaning of the exhibition. Before I left, I asked if errors took place with error CS0246. She told me, “Despite us restricting people from entering, the reception was better than we expected. Having something beyond our expectations means is a creative thing, and that there’s room for analysis. I hope to make more errors in the future.” Post-exhibition, the book, Jikochudokukeihatsu, published by Kakeru Okada’s publishing company, Paper Company, will be available on their website. NADiff a/p/a/r/t will be available for purchase at their physical store. Keep an eye out for the new direction of exhibitions led by this up-and-coming curator.

■error CS0246

This exhibition was curated by Kakeru Okada. It investigated exhibitions post-coronavirus, the possibilities of creativity, and dealing with aspects he hadn’t before. It showed from January 7th to February 23rd, 2021 at Alt_Medium, featuring Osamu Kanemura, Hiroko Komatsu, and Yu Shinoda. This interview was about the first installment of Hiroko Komatsu’s solo exhibition, Jikochudokukeihatsu, where visitors were prohibited from entering (if visitors wished to enter the venue, they had to reserve in advance and pay a fee of 3,000 yen).

■Exhibition History Vol. 1 by Hiroko Komatsu, published by Paper Company (300 signed copies) Hiroko Komatsu has been creating art based on materiality, a topic often overlooked by photographers. This photo book is a compilation of seven of Komatsu’s exhibitions (including Jikochudokukeihatsu) from her first solo exhibition in 2019, Titanium’s Heart, to Parallel Ruler, which was open in July 2012. It’s a statement on her exhibitions, which boasts an overwhelming amount of materials. It also includes personal photos, documentation, diagrams of exhibitions, DMs, and such. It is a comprehensive look into Hiroko Komatsu’s body of work while illuminating her works from a different angle.

■Past exhibitions

November 2009, Titanium’s Heart, Gallery Yamaguchi, Tokyo, Japan

November 2010, Speedometer Gallery Q, Tokyo, Japan

July 2011, Organic Contexture of Capital, Gallery Q, Tokyo, Japan

November 2011, Expansion Slot, Toki Art Space, Tokyo, Japan

November 2011, Suicide Diathesis, Yokohama Civic Gallery Azamino, Kanagawa, Japan

February 2012, Son nom de Broiler Space dans Calcutta désert, Citizen’s Gallery, Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan

July 2012, Parallel Ruler, Gallery Q, Tokyo, Japan

Author: Hiroko Komatsu, Editor: Kakeru Okada,

Contributor: Gen Umezu Designer: Daichi Aijima

■Jikochudokukeihatsu by Hiroko Komatsu, published by Paper Company (300 signed copies)

This photo book is a documentation of Jikochudokukeihatsu, Hiroko Komatsu’s solo exhibition, which is the first series of error CS0246, a serial exhibition by Hiroko Komatsu, Osamu Kanemura, and Yu Shinoda. This exhibition was held during the emergency announcement period, so entry into the venue was prohibited. Visitors appreciated the show from outside, through a window. The audience could watch things like the rolls of photographic paper changing shape over time. It explored the contradictory relationship between exhibiting and preserving art. It was a “no entry” exhibition and a space to preserve photos at the same time. Alongside the pictures of the show taken by Hiroko Komatsu and Yu Shinoda, the book includes photos taken by a camera that was installed in the space.

Author: Hiroko Komatsu, Editor: Kakeru Okada, Contributors: Yuri Mitsuda, Hiroko Komatsu, Kakeru Okada, Translator: Peiai Sun, Designer: Daichi Aijima

Kakeru Okada was born in Tochigi prefecture in 1989. He graduated from the College of Image Arts and Sciences, Ritsumeikan University, in 2012. In 2015, he graduated from the Graduate School of Film and New Media, Tokyo University of the Arts. Some notable exhibitions he planned are Osamu Kanemura’s Copyright Liberation Front (The White, Tokyo, 2020), HakHyun Kim and Osamu Sakuma/Rodande’s imshow (kanzan gallery, Tokyo, 2020), Yusuke Endo, Shingo Kanagawa, and Osamu Kanemura’s imshow (kanzan gallery, Tokyo, 2020), Iwasaki Hiromasa and Yu Shinoda’s imshow (Alt_Medium, Tokyo, 2019), and Medias (Yokohama Civic Gallery Azamino, Kanagawa, 2019). Also, alongside planning exhibitions and curating them, he founded the publishing firm Paper Company. He sells and makes compilations of photos, photo books.

https://kakeru-okada.com/

Hiroko Komatsu is a photographer born in Kanagawa prefecture in 1969. She received the 43rd Kimura Ihei Award. From 2010 to 2011, she held a solo exhibition monthly at the independent gallery, Broiler Space. Her recent exhibitions include DECODE / Events & Materials, The Work of Art in the Age of Post-Industrial Society (group exhibition, The Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, 2019), Mirror Behind Hole – Photography into Sculpture Vol.4(solo exhibition, gallery aM, Tokyo, 2017, curated by Yuri Mitsuda), The Power of Images (group exhibition, MAST, Italy, 2017), and so on. Her public collections: MAST (Italy), Tate Modern (The U.K.).

http://komatsu-hiroko.com/

Photography Yu Shinoda