Since he was in the fifth grade of elementary school, Tomohiro Nakano, a student at the University of Tokyo, has been trying to “create a conworld,” a literal epic feat. He recently gave a demonstration of his self-made conlang (or constructed language) at variety show “Tamori Club,” which blew up on social media. For this interview, Tomohiro reveals the reasons behind the creation of his conworld “Firraksnarre” and his ambitions towards the project.

——What made you want to start the creation of your conworld “Firraksnarre”?

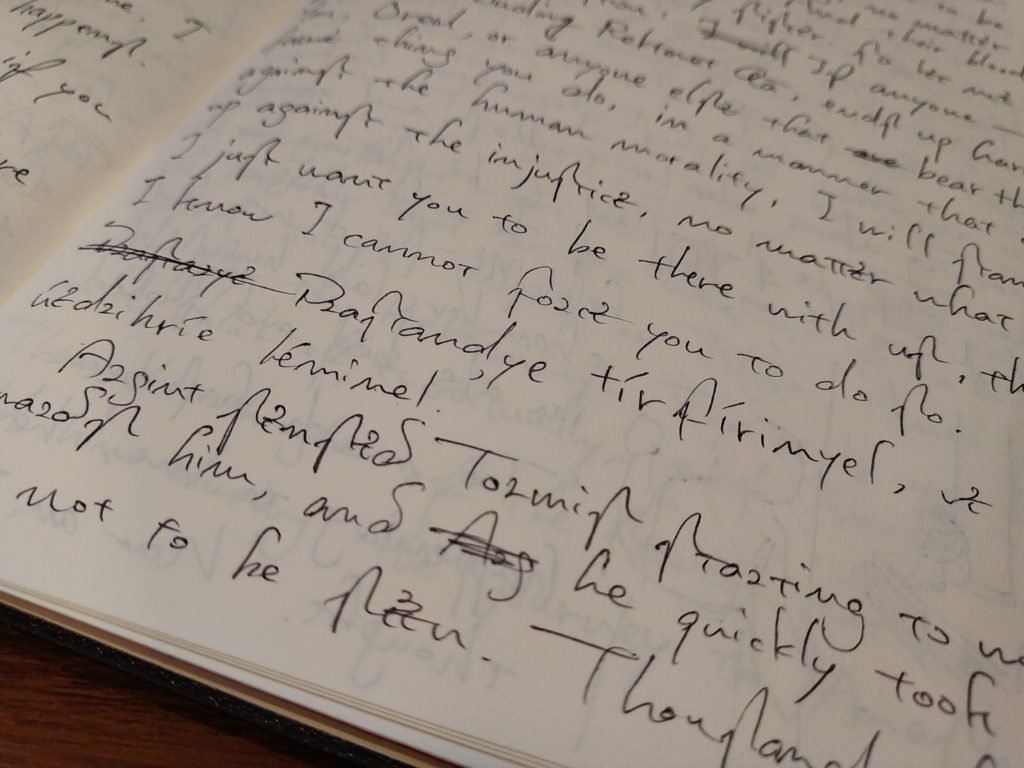

Tomohiro Nakano: I’ve loved fantasy since I was in elementary school, and I was particularly influenced by Harry Potter. Reading it made me want to start writing such a novel myself, so I started writing it in the fifth grade of elementary school. That was 2009, and I’m still developing the novel I started writing at the time.

After that, in middle school, I started reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings and realized how detailed the worldbuilding was, so I thought that if I were to do the same, it would have to be as intricate as if it actually existed. That’s when the creation of my conworld “Firraksnarre” began in earnest.

——Is conworlding any different from fantasy and science fiction?

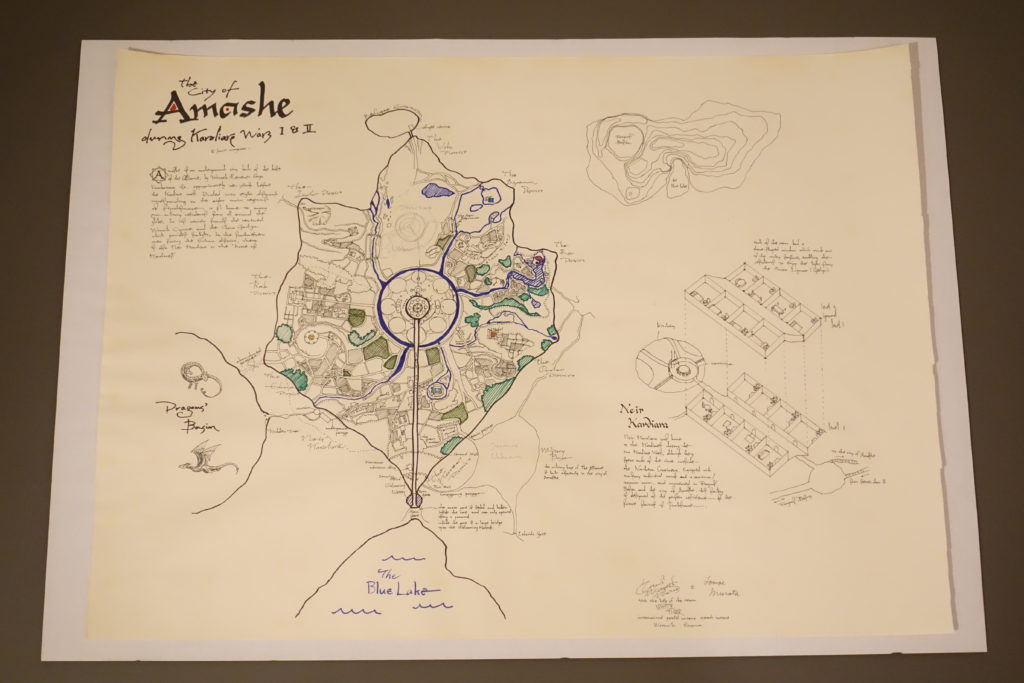

Tomohiro: The term “conworld” (short for constructed world) does not refer to just any fictional universe found in the genre of fantasy or science fiction, but those with extensive worldbuilding regarding the formation of the world itself, the history of humankind and other organisms, and the developmental processes of different cultures. The conworld “Firraksnarre” that I am creating aims to be a world that is “explorable” through getting to know the history and cultures of the people who live in it.

——It’s a project of epical proportions. How do you actually create a conworld?

Tomohiro: In my case, I write a story that works as the core, and then think about setting elements such as history, geography, language and culture and link them to the story. These elements are all based on real-life natural processes, so for example, to create a new language, I had to find out how actual languages like French and Spanish descended from Latin, and apply that essence to developing my languages. I do that not only for language but also for history and geography as well.

——You’re currently studying linguistics at the University of Tokyo; does that affect your creative process?

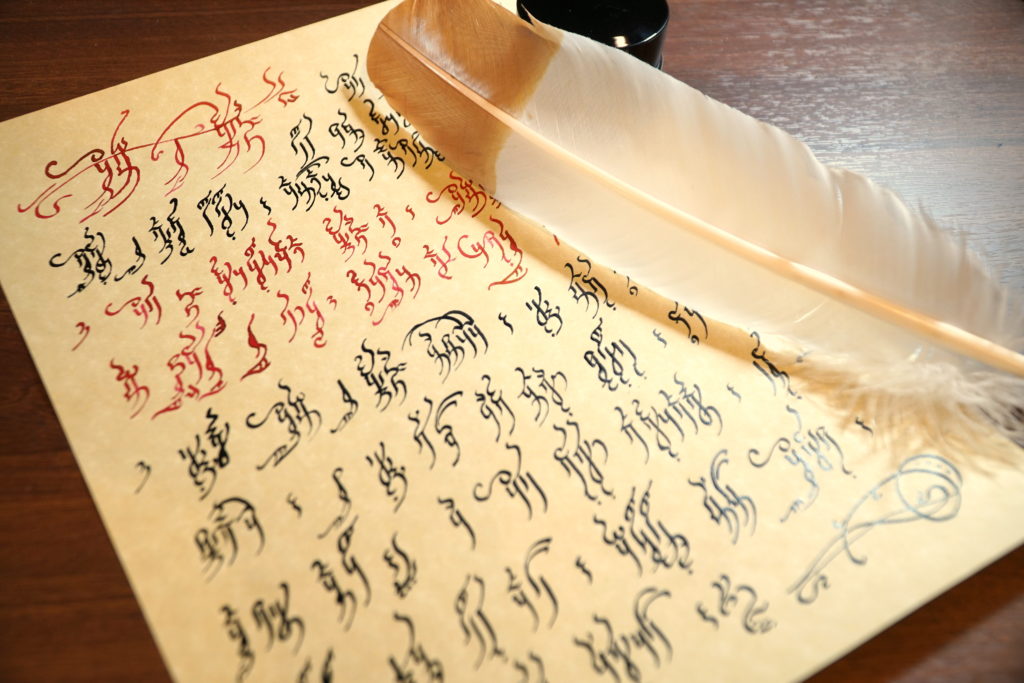

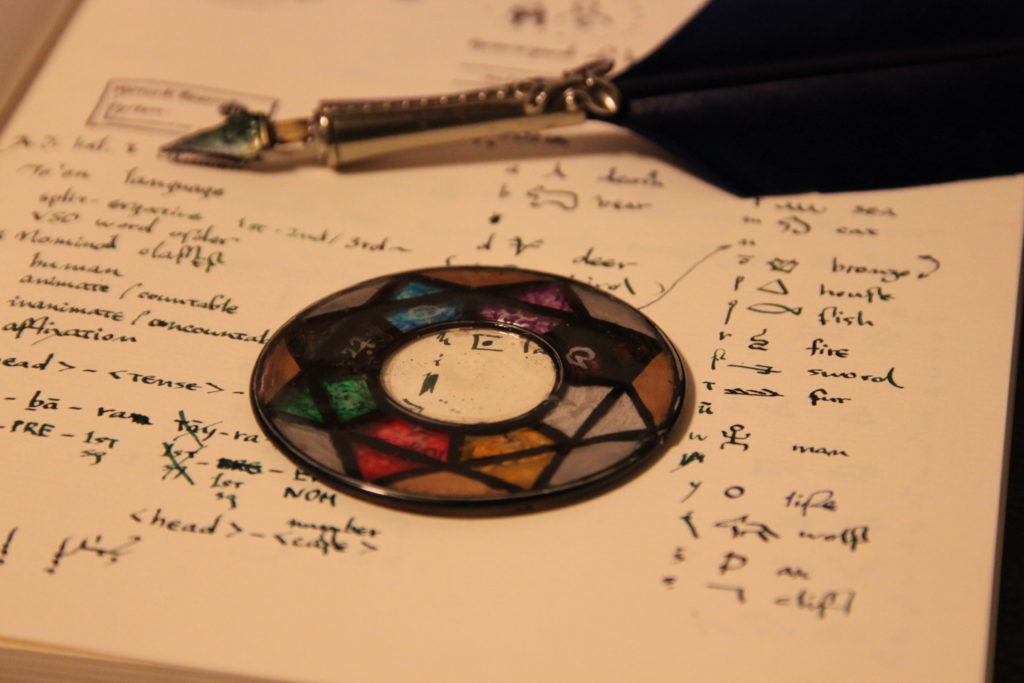

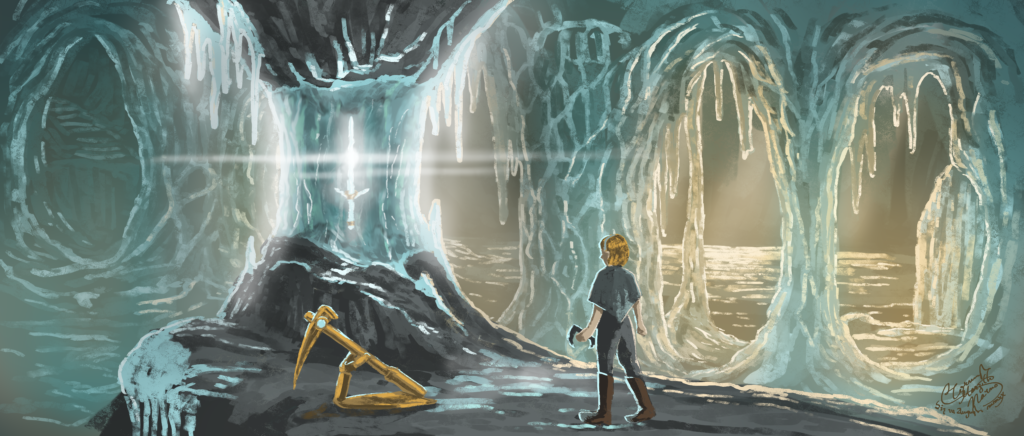

Tomohiro: It does. Tolkien was a linguist, so I thought I had to study linguistics if I wanted to create my own conworld. Whether it’s linguistics or other humanities, they all connect to conworlding in one way or another, so while taking classes, I’m always thinking about applying what I learned to what I create. Up to this day, I’ve personally created a considerable number of constructed languages, each with its own level of completion. I’ve also made a live-action movie called Between the Two Worlds based on “Firraksnarre,” in which I actually used my originally made conlangs.

——I can’t really picture where to start when creating a language.

Tomohiro: There are different fields in linguistics, but I’m particularly interested in phonology, which deals with how the speech sounds of a language are arranged and such. From a certain point of view, language is essentially a signal created with sounds, so in theory, you use your knowledge of phonology to start on the level of phonetics and phonology, gradually increasing the scope to morphology and syntax. First, you combine sounds and make words, then phrases, sentences, paragraphs, and so on.

There are many sounds in the world that Japanese doesn’t have, so when creating a conlang, the best practice is to use the International Phonetic Alphabets (IPA) and select which sound to use from them; that would be the first step of the process.

——How do you assign a certain “meaning” to a certain “word”?

Tomohiro: According to linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, the connection between the signified and signifier is arbitrary, so the creator has no choice but to come up with ideas to assign the meaning to the form. In addition to that, as a guideline, there is also a hypothesis stating that a specific sound might be linked to a specific appearance, feeling, or tactile sensation, to some extent; onomatopoeias are considered to be an example of this.

Furthermore, as a general example, there is also a cross-linguistic tendency to use vowel sounds like “ah” or “oh” for large things, which are pronounced by opening your mouth wider than “ih” and “eh” sounds; those would be used for smaller things, as the sound is produced by narrowing your mouth. I think this is related to how humans perceive the world around them, and so I make decisions in reference to that.

Originality in storytelling

——I think Tolkien’s works influence you in terms of storytelling; what’s your opinion on originality?

Tomohiro: Originality is something that every creator struggles with. For me, the process of digesting what influences me is the most important. I feel that recent Japanese fantasy games and light novels are heavily influenced by Tolkienian fantasy. In my opinion, there is a need to get out of this stage. Now I feel like it’s the time to update the fantasy genre.

The fantasy boom that started in the early 2000s finds its roots in the film adaptations of Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings, and I feel that since then many works of fantasy influenced by the source material of The Lord of the Rings have been mass-produced. Meanwhile, Game of Thrones was recently very successful, and I personally think that it’s because they did something a little different from Tolkien’s worldbuilding. I would like to establish my own originality, or rather, something that only I can make, by creating something new.

——In a past interview, you said that “many use the fantasy genre as a business tool to mass-produce empty works.” Can you explain what you meant by that?

Tomohiro: Of course. I find this problem deeply troubling. I feel that most people don’t care about detailed worldbuilding; both developers and consumers. Looking at these works I always end up thinking to myself: “Could this imaginary world scientifically exist?”. By refining and adding detail to the worldbuilding, I think I can definitely provide something new.

The significance of creativity

——It’s incredible how you started this production in the fifth grade of elementary school.

Tomohiro: I’ve also had difficult times. When I was in middle and high school, nobody would understand me. It’s partly because I was going to a high-level school so everyone was focused on studying and they would only judge you by your grades; the people who would care about creative works in that kind of environment were very few. Since I got into university, more people have started to acknowledge my work, so more often than ever I feel happy about having carried on up until now.

I think there are a lot of creatives who stop doing what they love because they aren’t understood by the people around them, but I kept working at it, and eventually, I was picked up by the media and so on, and that brought me to where I am now. There is a better world waiting for people who keep at it, or at least I hope so.

——In the pandemic, do you feel some kind of societal pressure keeping you from working creatively?

Tomohiro: The production of my movies was suspended because of the coronavirus. After that experience, sometimes I found myself thinking about how useful what I am doing is. However, during the quarantine period, I made my previous movie available online for free, and the number of viewers increased. That’s when I understood that people needed creative content too. Even if it doesn’t directly impact society like political science or economics, it’s necessary to create something that people can enjoy.

——On your Twitter page, you pinned a comment which states: “Who decided that people can’t contribute to society through creative work? I’ll show you how it’s done.” What thoughts and feelings are behind this?

Tomohiro: As I said earlier, some people believe that linguistics is a useless science. I still don’t know how I could contribute to society through my research. However, I also think that doing what only I can do is the most important thing at the end of the day; that for me is creating content. I pinned that tweet with this kind of determination in my mind.

That said, I haven’t been able to contribute to society yet, so I think it’s important for me to continue thinking about what I can do.

——You’re graduating from university next year, and I heard you’re planning on going to graduate school. Will you continue to study linguistics?

Tomohiro: Yes, I will. I’d like to keep creating while I continue my research in linguistics. I am thinking of studying abroad in the future. Right now, I am mostly interested in Celtic languages and historical linguistics: where they came from, how they evolved, etcetera. I really want to apply my knowledge I obtained through creating languages to the research of Celtic languages, but in Japan, there is limited access to the necessary resources, so it would be pretty hard to do so from here. It’d be best to go to where it’s possible to access said resources directly, collect data and research.

Tomohiro Nakano

Born in Kyōto in 1998. Tomohiro was raised in Ōita and Yokohama. He writes novels and movies using his own constructed languages. The information on the production and screening of his movie Between the Two Worlds based on his conworld “Firraksnarre,” and its sequels Fragments of Hope and Light of Eternity, which are currently under production, is available on the films’ official Twitter. His upcoming goal is to publish his first novel.

https://tomohironakano.com/

Twitter:@TormisNarno_JPN

Photography Kazuo Yoshida

Translation Leandro Di Rosa