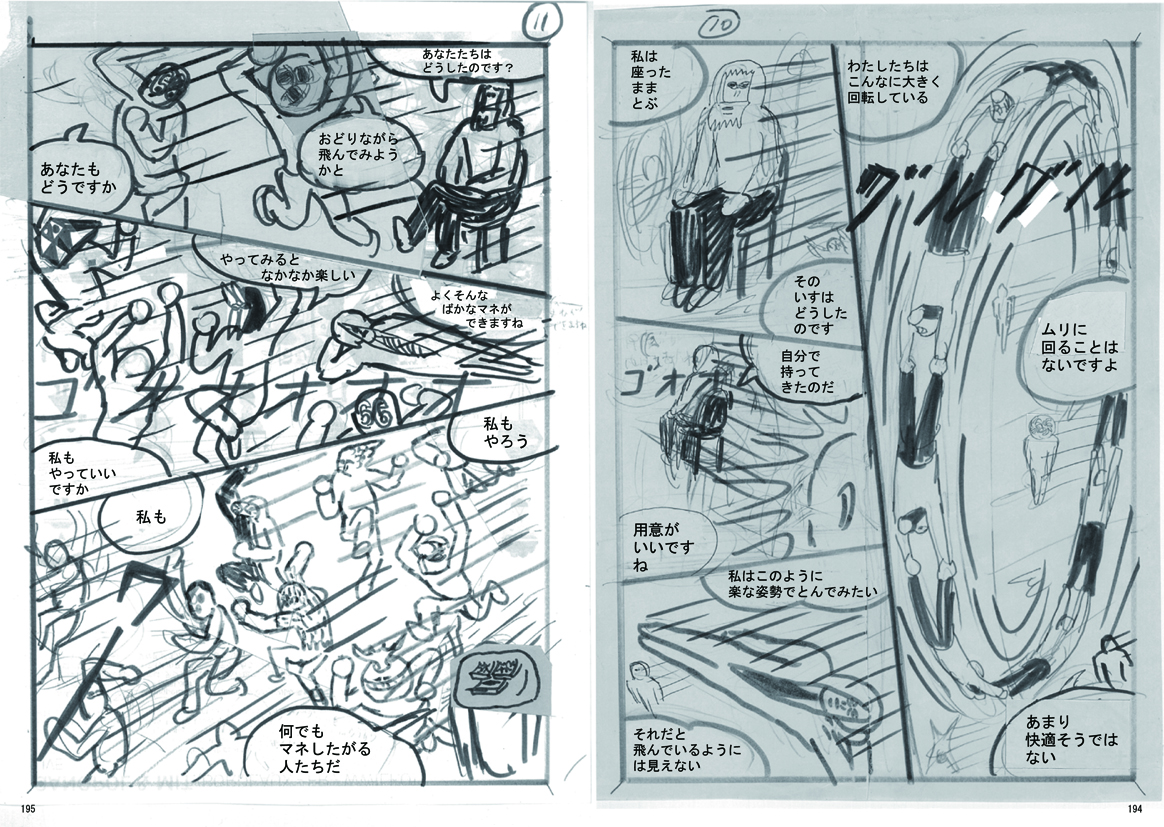

Character designs not matching any previous style neither from the East nor the West, onomatopeias such as “do do do do” and “go ro go ro” expressing a sense of speed, time depicted in equal intervals; these characteristics belong to Yūichi Yokoyama’s “neo-manga.” This mysterious and overwhelming art style focuses on its expression of the passage of time through cluttered yet dynamically-drawn series of panels, evident in most of Yūichi’s works, such as New Doboku (In Japanese, new engineering), which exclusively depicts scenes of engineering work, and Travel, portraying different situations regarding travel by train without a specific purpose or destination.

Ex-oil painter, now mangaka Yuichi Yokoyama was featured in the French political daily newspaper Libération, also famous for its deep insights into pop culture; Yūichi also held different exhibitions at the Anne Barrow Gallery in Paris, the Palais de Tokyo, and the Haus Konstruktive Museum in Zurich, gaining recognition around the world; his characteristic style “neo-manga” has been critically acclaimed as it redefines the classic constructs of manga, although what we see now is completely different from what Yūichi originally had in mind.

A series of scenes instead of a single picture

――You went from contemporary art to manga; how did you achieve your art style?

Yuichi: I graduated from Musashino Art University’s oil painting department, and neo-expressionism was popular at the time. There was also this mood of having to make large-scale artworks, and I admired contemporary art, but I didn’t have money to buy oil paint, so I used plywood and house paint instead. I worked with those for a few years and even applied for some contests, but I didn’t win any. As soon as I stopped working on wooden panels, I won a contest from the Japanese magazine illustration. After that, I started getting more illustration jobs, and I was gradually able to support myself. Therefore, I’ve already given up on contemporary art once: a complete defeat for me.

――Why did you shift from illustration to manga?

Yuichi: It’s because I started drawing manga while I was working as an illustrator. Plus, at that time, I felt some sort of emptiness or unsatisfaction in drawing only one picture. I didn’t want to express myself with just one picture; I wanted to draw what happens after. However, the story didn’t matter to me, and it felt comfortable to draw an illustration comprising a series of scenes. That’s when I thought of manga.

――Is the lack of a clear storyline part of your artistic approach?

Yuichi: It sounds cool if you say it like that, but it just felt comfortable like that.

――What in particular made you feel empty or unsatisfied when drawing single pictures?

Yuichi: I didn’t want people to ignore my art; I wanted to feel safe in that regard, to have a place in society. Unless you’re a well-known painter, you won’t get many customers for your solo exhibitions. I was concerned about the number of people; how well my art would spread. A manga won’t sell that much, but at least five, six thousand people will read it.

The good thing is that in contemporary art, nobody really cares about that. There are some famous artists in the industry, but they’re not globally known. The fact that viewers cannot understand it may be a matter of level, but it still felt like a closed yet empty environment. The people who can immerse themselves in their work without worrying about such things are those who are actually able to keep working in fine arts. I’m not good at calming myself down and facing my heart when I work; I can’t feel comfortable.

――A feeling that questions the viewer’s insight.

Yuichi: Appreciating contemporary art also needs some effort, in a way. As with abstract paintings, it’s hard to put into words how you feel when you understand such art; you have to get closer to it. Japanese painting has both elements: both high-level viewers and people who aren’t experts can understand it. The same can be said for Ikuo Hirayama’s works. My father had no background in fine arts, but I liked Hirayama-san’s paintings.

――They’re pop and easy to understand but in a good way.

Yuichi: Japanese painting is just one example. Contemporary art is close to the feeling of finding an unknown continent and settling before anyone else. The feelings of excitement and joy you get when you discover it is awesome, as well as the respect you get. Right now, there aren’t a lot of works like that around, though.

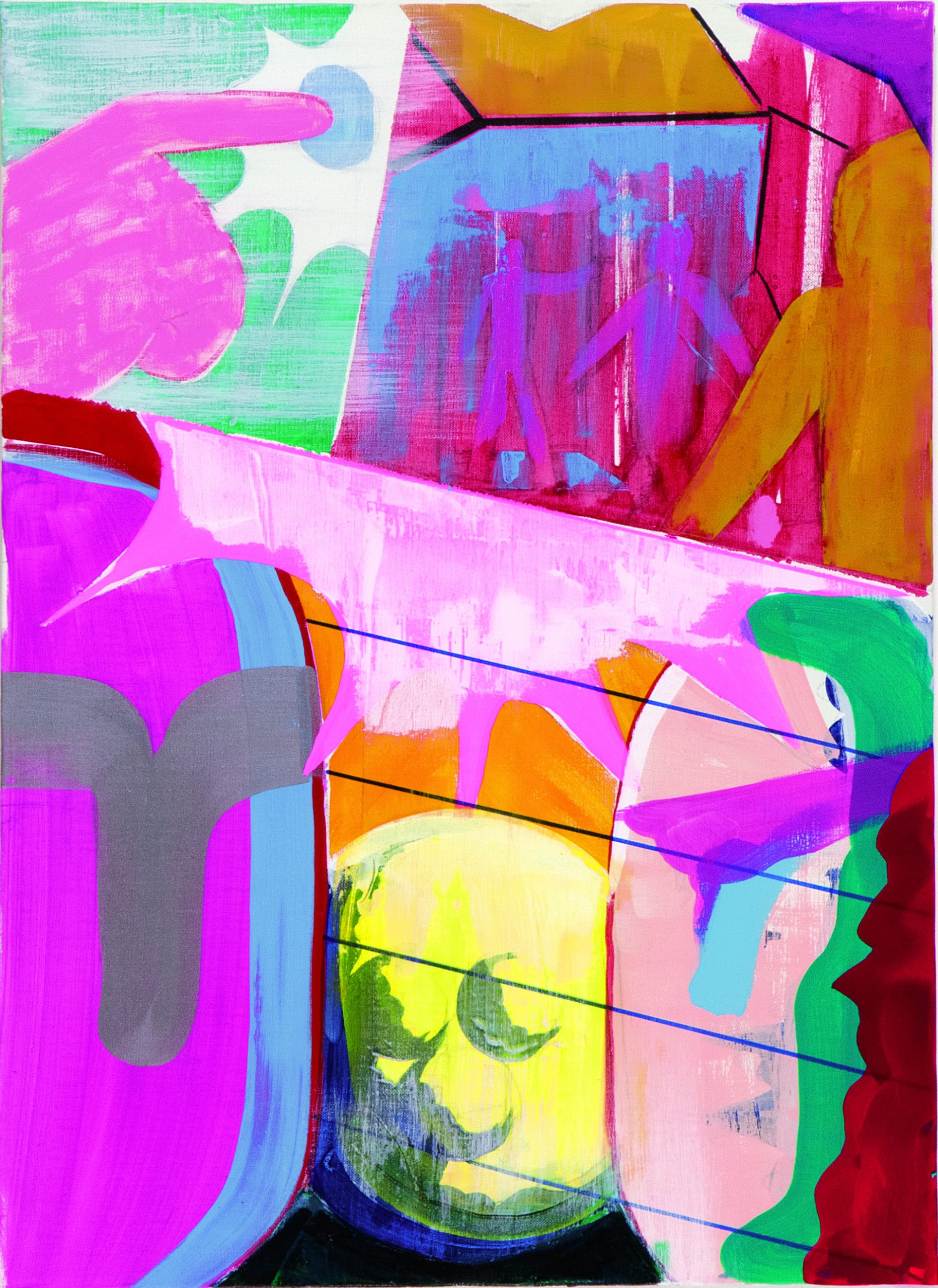

©Yuichi Yokoyama Courtesy of NANZUKA

Characteristic onomatopoeias and the influence of mangas from early childhood

――Are there any artists that influenced you?

Yuichi: When I was a student, Tadashi Kawamata’s People’s Garden left an impression on me: I was studying academic painting at school, and I felt that something had to change. He still influences me, and I want to surpass him. You could say that it’s why I still write manga. I guess I couldn’t surpass him with painting. Also, there was a time when Vermeer’s paintings were the protagonists of the fine arts of the past, but are painters still the protagonists of fine art? I find myself asking this question sometimes.

――Do you mean that the protagonist is not visual art anymore?

Yuichi: I would say it’s something like a game creator or something similar. When scientists examined dinosaurs’ skeletons and other details related to the wings, they found out that dinosaurs evolved into birds, not reptiles; similarly, a child who has been exposed to fine arts and Vermeer’s paintings may just not draw anything at all. It’s the same with words and sounds, even eras: the content changes depending on the listener/viewer’s impression. In that respect, onomatopoeias are cool because they’re universal.

――Last year, you released Moeru Oto (In Japanese, burning sound), in which fast-sounding onomatopoeias such as “do do do do,” “mo mo mo,” “bi yo yo yo” actually become three-dimensional flames. Where does this concept come from?

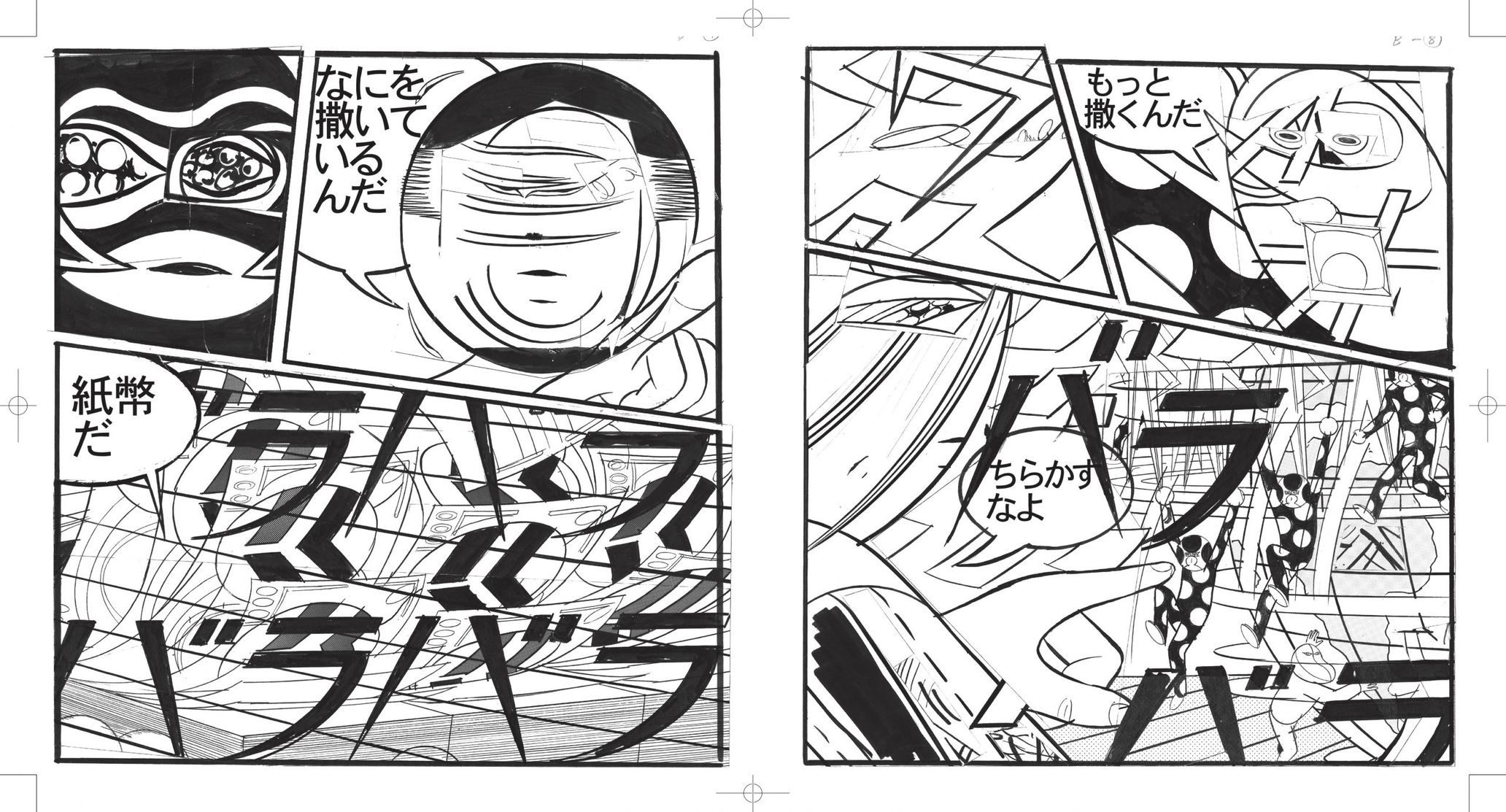

Yuichi: I started drawing manga without being interested in it in the first place, so I can only say that it happened naturally. When I was a kid, I used to read Dokaben, which is about baseball, so baseball games are often depicted using distinctive onomatopeias like “kaan,” or “waa waa.” My onomatopoeias are imitations of those. It’s probably the influence of vague childhood memories, so I imitate them. They’re also convenient for filling the screen and adjusting time. My art is uniform: every panel is equally timed, so if I decide they’re all two seconds apart from each other, I can use onomatopoeias as time adjusters; I can use them to explain the story, too.

Some time ago, I was interviewed by a German person who asked me what onomatopoeias were and if I had invented them; I told him they’re pretty normal for Japanese people, to which he replied by saying that they were too primitive. I’ve also been told that they’re inefficient and illogical, so maybe German people don’t really like them. I haven’t been able to publish even a volume in German-speaking countries.

©︎Yuichi Yokoyama Courtesy of 888books

――In Travel, there are no onomatopoeias at all.

Yuichi: That’s why it was hard to draw. Without onomatopoeias, it’s hard to fill empty spaces; if I didn’t want to write detailed hands, for example, I’d use them to fill the space. The Germans’ reaction was the opposite, but I still think that onomatopoeias are very logical. Everyone uses them normally, and in my case, I just draw them with a ruler, so I guess they look a bit different.

Drawing without being bound by time and space

――I read in an interview that you draw most of your lines with a ruler.

Yuichi: Not recently, but in general, yes. I don’t trust freehand drawing, or rather, for better or for worse, in the world of fine arts, there’s a tendency to emphasize the warmth and touch of the human hand, and it feels a bit gross to me. I like that feeling of trying to get rid of the “human body smell,” as people in Ukiyo-e and ink wash painting. At first, I started drawing using templates and rulers for technical reasons since I couldn’t draw a straight line at all, but then I noticed how the “human body smell” would disappear, and I thought it looked cool; bonsais are the same: the branches are supposed to grow straight, but we fix them with strings and threads to create a distorted shape. It feels like the artificially created boundary between nature-made and human-made becomes blurry. Instead of extending, it’s expressing itself within its limits.

――I wonder if, with freehand drawing, it’s easier to draw lines that aren’t straight or in an already pre-existing shape.

Yuichi: In the case of painting, it’s definitely more interesting that way. However, Japanese painting has its rules and formats, which limit the artist’s freedom, so you have to work with that. I think that there’s a feeling of liberation in that, and it’s easier to draw characters and write stories with manga’s limitation.

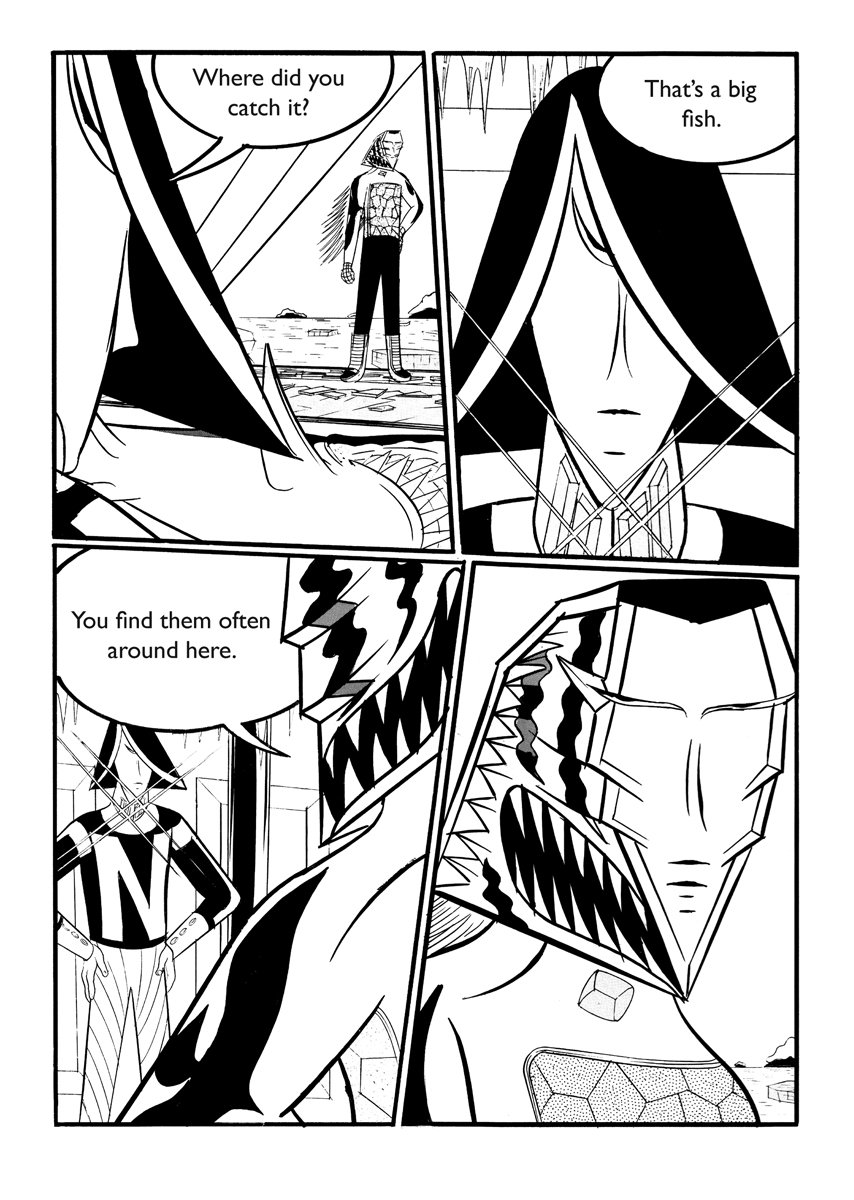

――You posted on Twitter that you would like to write a manga with recurring characters. The protagonists of your mangas are expressionless, they look unusual, and they wear unusual clothes; even their nationalities are unknown.

Yuichi: That’s probably because it gives a sense of security. In old European works, some characters are not directly related to the theme: for example, Delacroix’s nude paintings of women in the French Revolution, which make me feel uncomfortable. I want to make something universal, unbound by the limitations of time and space. You can tell from which period a painting comes from by looking at how meticulously drawn the clothes are. I try as best as I can to erase any trace of real-life setting from my art as well; people shouldn’t be able to guess if it’s art from the East or the West; I don’t even draw phones. A celebrity wouldn’t appear as a character, even by mistake. I don’t want to deal with the present situation, or rather, human emotions in general.

――Is there a reason you don’t want to focus on human emotions?

Yuichi: Most of what’s trending right now is based on human emotions, even on television, where negative feelings such as anger and sorrow are noticeable the most. Isn’t there way too much expression of human emotions in society? Is it art’s role to analyze and help people digest emotions, or should we able to do that in our own life? That’s what I’m asking myself.

――It connects to the relationship between the art and the viewer that you were mentioning at the beginning of the interview.

Yuichi: To put it badly, I’m not taking responsibility for my art since I’m doing only what I want to do. What I find interesting is the kind of writing and expression that simply shows a scene after the other without showing emotions, like in Hemingway’s and Masuji Ibuse’s novels. They feel really cool and modern, don’t they?

Not knowing how to write manga as the reason behind the unconventional art style

――You described Moeru Oto as “an experimental manga that imitates modern poetry and minimizes the narrative.”

Yuichi: The three short stories in the book, Moeru Oto, Shutsugen (In Japanese, appearance), and 30 Seiki (In Japanese, 30th century), are written to seem like the previous line connects to the next. In truth, the connection has no meaning or relevance whatsoever. At first glance, everything seems connected like in prose poetry, but it’s actually not. However, it’s something you’ll want to read again after. Once I read a novel, I won’t read for the next 30 years, but I’ll read the same modern poetry book over and over again. I also like the selfishness of completely leaving everything in the hands of the reader.

――(In Japanese,) all the lines are written horizontally instead of vertically. Is it because you were thinking of publishing your books overseas? Have you ever felt uncomfortable with horizontal writing?

Yuichi: I learned that dialogues in normal mangas are written vertically and in Ming typefaces after publishing. It’s just a case: the lines asked my friend to write were written horizontally. The format size was also wrong, but I don’t care. Not caring about the format means that fans of ordinary mangas won’t like it, though. My classmate from prep school back in the days, Usamaru Furuya, has always loved manga. If you work in a pre-established culture like him, it’s easier to get fans, but I don’t have that.

――You tried writing gag comedy with Room: what’s your definition of gag comedy mangas?

Yuichi: My first experiences with gag comedy mangas was when I used to read Tensai Bakabon and Macaroni Hōren-sō as a kid. Even if I read it now, I can see the high level of production in Tensai Bakabon. Macaroni Hōren-sō used to be fun, but I doubt it would work in this era. The weird heavy metal character was also a wonderful 4th batter back in the days. In that respect, gag comedy can risk becoming obsolete in time. While I think it’d be best to not write any, but I want to, at least once. You can make comedy works with just words, but if you don’t use them, it should be quite difficult.

By the way, Room is actually my favorite, and I don’t read the same manga more than once, but I still read Room and Moeru Oto from time to time. Room is just funny; it’s really just funny, but I guess some people may find it boring because of that.

©︎Yuichi Yokoyama Courtesy of 888books

――People really appreciate your colorful paintings and drawings and contemporary art, as well as your mangas. Since you studied contemporary art, did you find that knowledge useful while writing manga?

Yuichi: I guess that would be the technical part of drawing pictures. All my works with color are just imitations of Hokusai, so anyone can make them. Just like Hokusai’s prints, it’s simple assembling. If you don’t use strong colors and place highly saturated colors at small points to make the picture look flat, like with black and white photographs, your picture will look like a Hokusai’s. The colors should be as light and as weak as possible.

I get a commission for colorwork every few years, but I really shouldn’t do it. They don’t sell the old screentone textures anymore; there are many obstacles. I try to run away with all sorts of excuses, but sometimes I get caught, and I draw. I’m actually drawing right now.

――Can you tell us about what you’re going to draw in the near future?

Yuichi: There will actually be a group exhibition on faces at the Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art in Marugame City on March 20th. Also, I think I should draw manga myself. It’s all about the obligation to draw on time, but the moment when you get your first idea, and the moment when you finish drawing are fun. Between those, it’s just pain and boredom.

Yuichi Yokoyama

After graduating from Musashino Art University’s oil painting department, Yūichi made his debut as a mangaka in 1995. So far, he has drawn many mangas such as New Doboku (East Press, 2004), Travel (East Press, 2006), NIWA (East Press, 2007), Outdoor (Kodansha, 2009), Color Doboku (Picturebox/NanzukaUnderground, 2011). PLAZA(888books、2019)Yuichi is critically acclaimed not only for mangas but also for colorful paintings and drawings, which have been displayed in various exhibitions and galleries in Japan and overseas, such as “Yuichi Yokoyama x Surrealism” (Miyazaki Prefectural Art Museum, 2014), “Yuichi Yokoyama: Wandering Through Maps, Un Voyage a Travers Les Cartes” (Pavillon Blanc, Colomiers, France, 2014), “Sekai ha hen da! Tiger Tateishi+Yuichi Yokoyama no Manga to Kaiga” (Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, 2016), “Yuichi Yokoyama Exhibition” (Nanzuka, 2020).

■ Infinite Variety of Faces

Dates: From March 20 to June 6

Venue: Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art

Address: 80-1 Hamamachi, Marugame City, Kagawa Prefecture

Open hours: 10:00-18:000 (Entrance is possible until 17:30)

Days off: Mondays (open on May 3rd), May 6th

Admission: JPY950

Translation Leandro Di Rosa