The Netherlands’ coronavirus lockdown initially began in December of last year, but after numerous extensions, it became a six-month, long-term lockdown. This spring, restrictions began to ease at last. On June 5th, the Dutch government enacted step three of a six-step plan for lifting the lockdown, allowing indoor establishments such as bars, restaurants, and art museums to reopen.

When I could visit an art museum at last, the first reservation I made was at Photography Museum Foam—the same venue that held Alec Soth’s exhibition, which I covered in the second installment of this series. Located in the World Heritage Seventeenth-Century Canal Ring Area of Amsterdam inside the Singelgracht, Foam is an ambitious museum with an entrepreneurial spirit and economic independence from the government. From the basement to the third floor, it simultaneously holds different exhibitions on each of its four floors. Foam is well-known as one of the best art museums to enjoy the latest art of our times.

There are exhibitions open for two 2020 awards right now. These two awards, the Foam Paul Huf Award and Foam Talent, are both organized annually by Foam. Because these awards are open to artists from all over the world, rather than just from the Netherlands or Europe, they always attract international attention. Both awards’ exhibitions opened at the end of last year, so the six-month exhibition period happened to completely overlap with the long-term pandemic lockdown and the resulting museum closures. Thus, the exhibitions were not open to the public for the majority of the scheduled period. However, Foam made the call to extend both exhibitions, so they should be on display for the entire month of June as the museum reopens.

In this report, I’d like to focus on the exhibition by the winner of the Foam Paul Huf Award.

Spanish-born artist Laia Abril’s (1986-) solo exhibition, On Rape: A History of Misogyny, Chapter Two, won the 2020 14th Foam Paul Huf Award. This award, which Foam has organized annually since 2007, aims to support young photographers; the winner receives a cash prize of 20,000 euros and a solo exhibition at Foam. Past recipients of the award include world-renowned photographers such as Pieter Hugo and Alex Prager, as well as Japanese artists Momo Okabe and Daisuke Yokota.

As the title suggests, Abril’s work is part of a long-term project that attempts to visualize the historical marginalization of women from the perspective of women. I’d like to touch lightly on Chapter One, On Abortion (2016). This work focuses on the issue of abortion, which is still not allowed by legal or religious rules in many countries, and visualizes the resulting danger and damage to women when abortions are not performed safely or freely. The exhibition was shown in the 2016 Les Rencontres d’Arles in the South of France and subsequently toured through a total of 10 cities, including New York, Chicago, Helsinki, Paris, and London. Through this work, Abril had already garnered international recognition, winning 2018 Paris Photo/Aperture Foundation PhotoBook of the Year, an international photography award.

This exhibition, On Rape, which is the sequel to that work, is also inspired by social issues related to women. In 2018, a court in Spain ruled that five men who had raped an 18-year-old girl were guilty of sexual abuse rather than rape, and the men were later released. This event sparked the largest feminist demonstration in the country’s history, and Abril was one of many who was galvanized by this event.

Why must we tacitly accept perpetrators in order to preserve certain powers and social norms? In this exhibition, Abril looks back at the history of rape to find the answer to that question.

The tragic stories told by the survivors’ clothing

The first room features eight large prints, nearly two meters tall, all of which are photos of clothing. Upon reading the text above the photos, I realized that these clothes had belonged to female rape victims.

A young girl in Colombia who was sexually abused by a teacher at her kindergarten. A woman who was disowned by her pastor father at age 16 for being a lesbian, and while homeless, was raped, impregnated, and experienced a miscarriage. A transgender woman at an American prison who was raped at knifepoint in her cell by a prison guard. A female member of the US military who was raped by her commander. This collection of photographs of women’s clothing silently reminds us that each horrifying confession is a real-life event.

While looking at these photographs, I thought about the Hulu original drama, The Handmaid’s Tale. In a Sci-Fi world where the birth rate is abnormally low, the remaining fertile women are considered the property of a privileged class and forced to give birth on behalf of those who cannot conceive. In practice, this takes place through ritualized rape and strict monitoring of the women’s daily lives. The story is so tragic that it may seem like a dystopian tale, but Margaret Atwood, the author of the original story said, “I made nothing up.” When I learned that the story pieces together actual abuse experienced by women all over the world, I realized that the sexual abuse of women has historically been tolerated and not even properly discussed.

To return to the discussion of the exhibition: Although we cannot see the survivors’ pictures, each person’s clothing is instead presented in the form of a photograph, which allows each experience to transcend its frame and take on a certain collective feeling. The collection of various images creates a space in which it is unavoidable to confront the reality and reasons why women, regardless of race, environment, age, or occupation, are victims of rape or must fear the possibility of rape—all over the world, day and night, past and present.

A reflection on history from the perspective of women

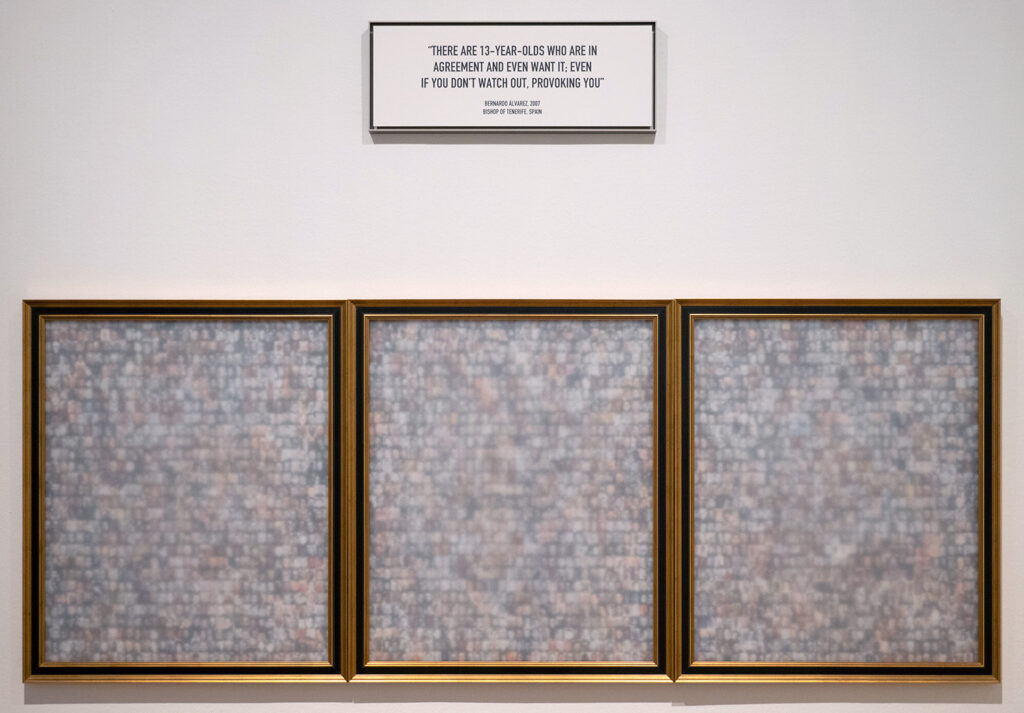

The next room displays still-life photographs featuring various articles of evidence of rape’s historical and tacit acceptance around the world. The photos include the following: A historical sculpture showing how throughout history, women have always been treated as trophies in the wars waged by men. A rape kit from America, where one woman is sexually assaulted every 73 seconds, and yet, thousands of rape kits containing DNA evidence have gone missing. Libido-reducing drugs given to convicted sex offenders and pedophiles in exchange for reduced sentences. A chastity belt manufactured in the Middle Ages to prevent rape. On display alongside this collection of photographs were panels containing quotes by powerful men from all over the world who justified rape.

If you are a man, when you see this exhibition, with its collection of objects and testimonies that are evidence of inhumane acts against women throughout the world’s history, you may think it only represents worst-case scenarios. Perhaps these are just events that happened in a small fraction of the world, and you may feel the artist is being malicious by disparaging the historical achievements of these remarkable men.

However, this exhibition is solely made up of objects, testimonies, and explanations of the historical tragedies women have gone through. While Abril organized the exhibition, nothing in it could be considered her personal declaration. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, this exhibition aims to look back at the history of rape to explore the reasons why perpetrators of sexual violence have been tacitly accepted. In this respect, she has merely collected and arranged historical facts in a calm, objective manner.

Even the word “history” could be interpreted as “his story”—a man’s story. Regardless of whether this is the etymology behind the world, history has indeed been recorded from the perspective of men. One could say that Abril’s multipart series, A History of Misogyny, is a “herstory” that re-examines history from the perspective of women.

History and herstory. On top of that, I think we could start a new discourse by getting to know the history of people with marginalized gender identities (i.e. “theirstory”) who do not fit within the gender binary. It’s incredible that Abril won a prestigious photography award prize for boldly telling women’s stories—stories that have been shrouded in secrecy until now. I’d like keep watching her as she unravels “herstory.”

You can see the 3D tour page of this exhibition at Paris’s Galerie Les Filles du Calvaire in 2020. Please take a look below if you’re interested:

https://embed.artland.com/shows/on-rape

■Laia Abril On Rape: A History of Misogyny, Chapter Two (The Netherlands)

November 6th 2020 – June 27th 2021

https://www.foam.org/museum/programme/laia-abril-on-rape-a-history-of-misogyny-chapter-two

Photography Tomo Kosuga

Translation Aya Apton