Culture can be born out of a specific time and place, and yet, it possesses the ability to become timeless. In this series, “時音” TOKION invites people who are shaping culture today, to talk about the past, present, and future.

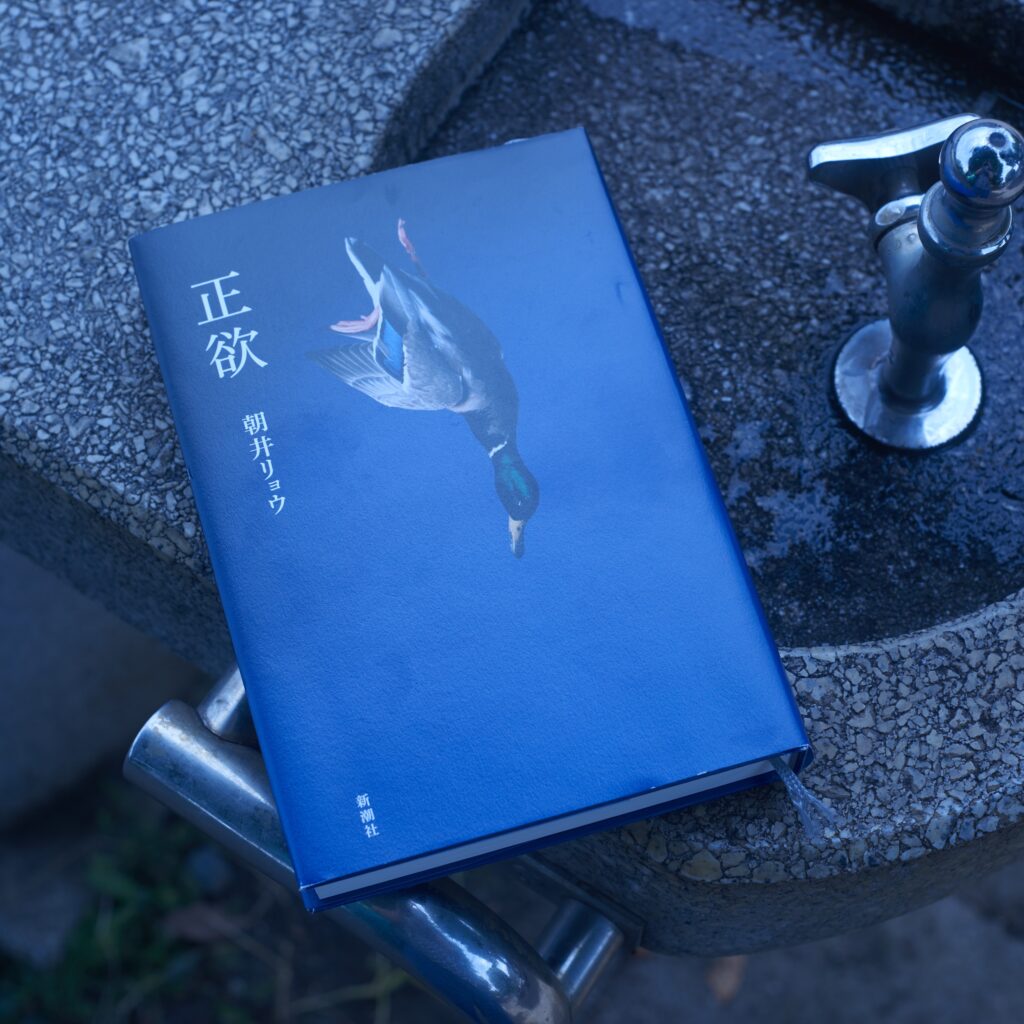

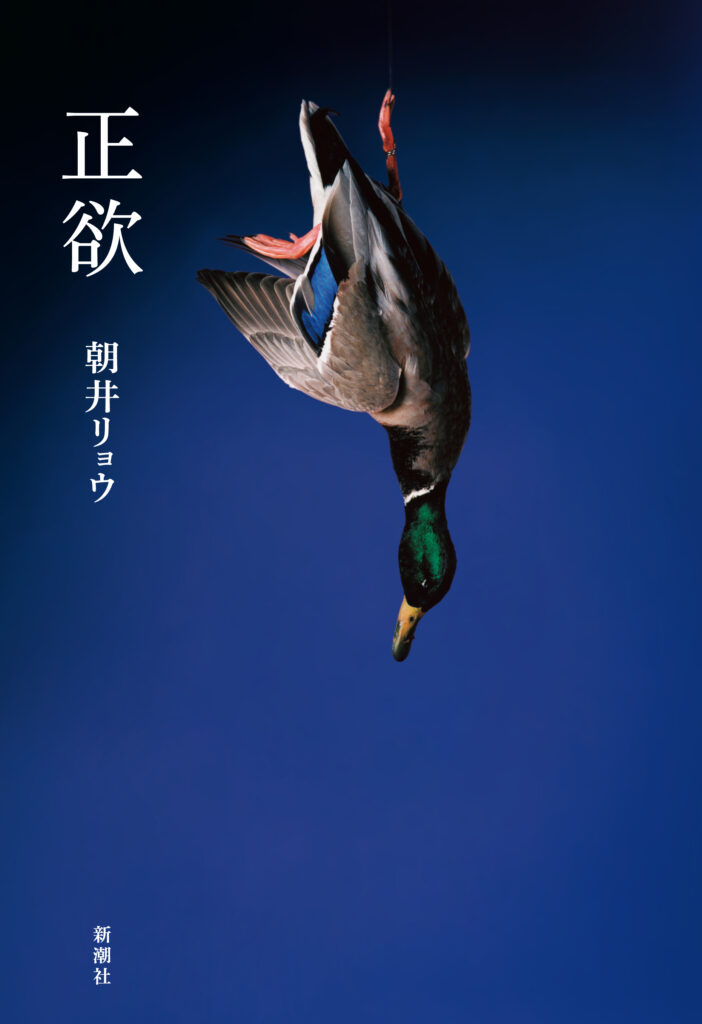

This time, we spoke to Ryo Asai, the author of Seiyoku, which was published this March to commemorate the tenth anniversary of his career as a writer. In Seiyoku, four characters take turns narrating the story based on themes of sexuality; it explores the relationship between the self and the world in a multilayered manner. Asai himself has described it as “A significant turning point for myself both as a novelist and a human being.” This book is bound to make waves.

In his 2009 debut novel, Kirishima, Bukatsu Yamerutteyo, Asai reveals the social hierarchy of school through the disappearance of its protagonist, and he illustrates the shift in how people communicate on social media via job hunting in Nanimono, which won the Naoki Prize in 2013. In Seiyoku, set in the transition period between the Heisei era to the Reiwa era, Asai addresses the reader to join hands to survive. As someone who has continuously depicted the zeitgeist and people’s innermost feelings in his writing, how does he view his doubts towards society? We asked him to look back on his career and talk about his outlook and story writing process.

Feeling alive because of the fervor generated by friction

——I’d first like to ask you about Seiyoku. I read in another interview that you came up with the title before the story. Could you talk about why you chose this title as well as its theme?

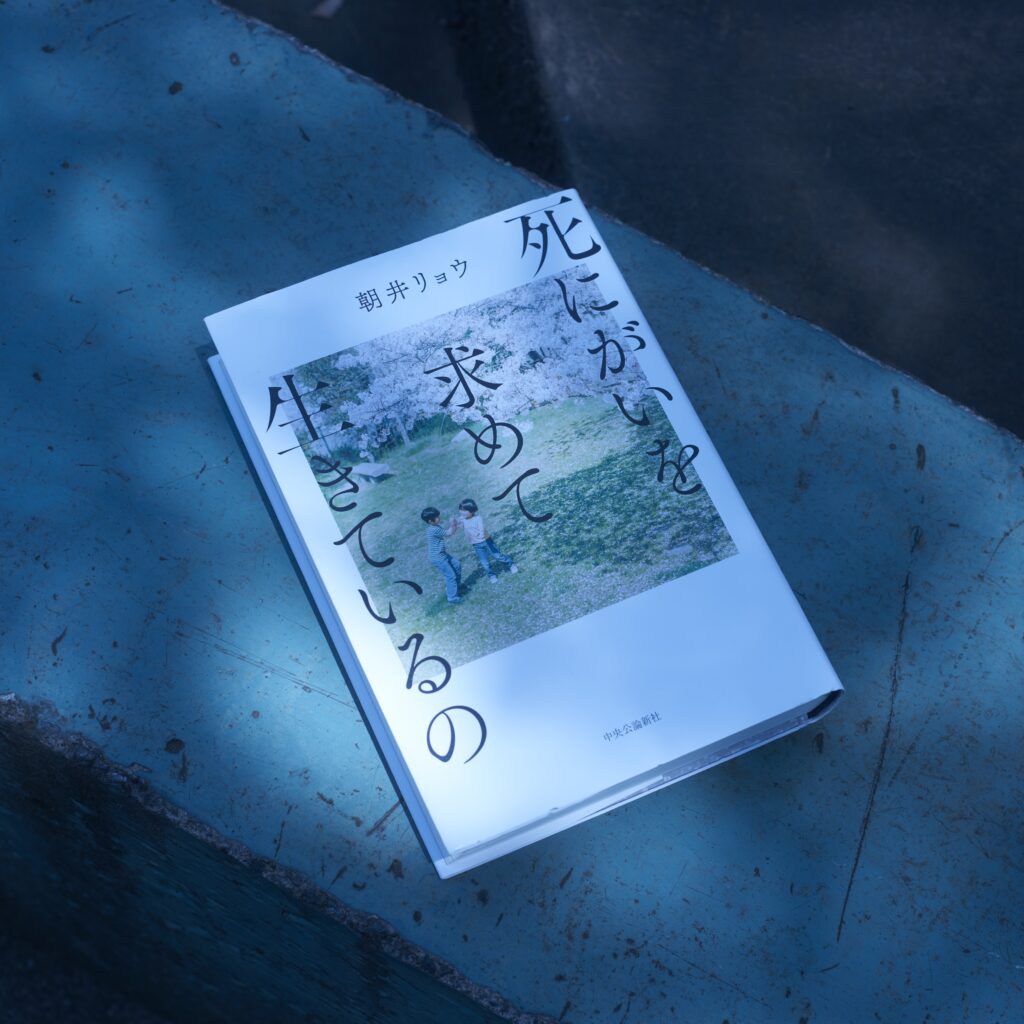

Ryo Asai (Asai): I wrote a novel, Shinigai wo Motomete Ikiteiru no, which influenced me when I wrote Seiyoku. It’s going to be somewhat lengthy, but allow me to talk about that first. I wrote Shinigai as a part of the Rasen Project in 2019, which involved eight groups composed of nine writers to write a full-length novel about the theme of confrontation, set in an era chosen for us. I was in charge of the Heisei era. When I was initially working out the plot, I couldn’t think of a symbol of confrontation during Heisei. If anything, I thought Heisei was about intentionally getting rid of conflict and growing up peacefully. [People were] like, “Everybody’s different, and everybody’s valid,” and “It’s the era of individuality.” But I felt we could understand individuality through differences between ourselves and others. Human beings [are creatures that] desire some role even if they get told to live their life freely. Of course, in many ways, it becomes easier to live when you get rid of confrontation. But when friction caused by that disappears, perhaps it becomes harder to sense one’s boundaries and the feeling of being alive.

——Do you mean the loss of conflict equates to the loss of feeling alive?

Asai: In my case, whenever an interviewer asks me something like, “What sort of motivation do you have when you write?” it sounds like they’re saying, “What sort of friction do you want to create between yourself and this world or society by writing a novel?” It’s like, “Would you still write even if you knew you’d generate no friction in others or society?” You could replace the word friction with influence or reverberation. This belief is deeply rooted in me: because of friction, fervor is born, and that fervor makes us feel alive. And it makes us feel like we have a role and meaning in life. If said friction embodies amicable relationships with others and society, then it’s not a problem. But I often wonder if I’d try to go out of my way to cause friction, even if that negatively influences others and society.

It’s hard to bring this up, but I also often recall the incident where the author of the manga series Kuroko’s Basketball was being threatened. At first, the perpetrator’s testimony centered on how he was jealous of successful manga authors as an aspiring manga author himself. But ultimately, he manufactured the motive in his mind: “[I’m an] aspiring manga author who’s jealous of successful people.” His tone then changed to something like, “I wanted to feel connected to society and other people by attacking someone.” Confrontation, friction, the connection between society and others, the feeling of being alive—although these things are distant from one another, I believe they belong to the same sequence.

——The absence of friction isn’t peaceful, as it means to stand on the brink of life and death. Perhaps that explains why we constantly covet it.

Asai: With Shinigai, I ultimately arrived at this exit: when all friction is gone, how can we feel alive without hurting other people or society? I felt like I was going to explore the same theme from another angle, eventually. In Seiyoku, the subject from the start is what factor would urge us to choose life from death. It’s about what could give us the drive to live.

When I read interviews of people who have achieved something, there’s a high probability for me to come across phrases like “I try my hardest for my family and kids” or “I try my hardest because of my family and kids.” I also see sentences like, “I started thinking about the next generation because of the birth of my kid.” Every time I do, it makes me acutely aware of the difficulty of using my physical body alone as fuel for vitality. At the same time, the fastest route to acquiring said fuel outside of one’s body is the family system. You need to have a sexual desire and orientation that fits the category of “being romantically and sexually attracted to the ‘opposite gender’” if you want to include yourself in a nuclear family. But you can’t pick your sexual desire and orientation. It’s possible for the things you can’t choose to become the source of your drive for life. The things I want to write about are narrowing down now: the relationship between sexuality and society, the relationship between life, death, and society, which inevitably changes because of one’s sexual orientation.

When I was a kid, I read a book about all the weird criminal cases in the world, and there was a person who committed a crime because of a particular sexual desire, which I also wrote about in my latest novel. It concluded that there are comical testimonies out there. But ever since I read that, I’ve always questioned whether it was okay for us to shrug our shoulders and say, “This person’s testimony is amusing.” Somewhere in the back of my head, I’ve always wondered what it must be like to live with that type of sexual desire. Seiyoku is a mass of different things from those long years of my life. Regarding the title, each person has a different sexuality, to the point that it might be pointless to attach labels because it’s a spectrum. And yet, when it comes to sexual desire, everybody has a part of them that feels guilty. That it’s a wrong desire to have, even though it could instigate a relationship with society. That’s where I got the idea to combine 性欲 (read as seiyoku, meaning sexual desire), a secretive sound, and the character for 正 (read as shou and sei, meaning correct, true, or exact), which has an open image. As I started writing the novel, it developed other meanings, and as a result, it became a very reliable title.

Entering new territory by accepting the state of not knowing

——The word diversity comes up in Seiyoku regularly. This line in the beginning, “I feel like one of the things diversity has birthed is simple-mindedness” is very impactful.

Asai: I’ve always had a problem with how people use the term diversity, not with the word itself. For example, I saw “The era of LGBT” on one dust jacket and “A symbol of the era of diversity” on another. It made me go, “No, it’s not like we’re in the era of LGBTQIA+, because they’ve always been here,” and “The era of diversity? People of all kinds have always been alive.” All of us exist within diversity in the first place. Diversity, meaning a state where there’s a lot of variety, exists first and foremost, and we’re just one small part of the many varieties. So, when I encounter a manner of speaking that acts like they’re the ones that discovered and recognized diversity, it makes me feel like they’re simple-minded. From what angle can one claim they understand and accept diversity? Is it even an option to reject diversity, to begin with, even if you’re a part of it?

The “LBGT goes against the preservation of the species” comment regarding the Equality Act became a much-discussed topic a while back. That person felt like they were on the knowledgeable side. They probably meant that gay people can’t have offspring when they said it. But not every aspect of society in which straight people have offspring is in the hands of straight people. We interact with each other in a complex way in this world. You can’t blame a group of people of a given background as those who go “against the preservation of the species.” Recently, I strongly sense the importance of being aware of ignorance and the inability to understand and imagine.

When I write and read novels, it feels like we’re living inside so many things we can’t imagine, let alone comprehend. I get how not understanding makes you feel anxious and that it’s tough to accept that.

I, too, am prone to want to be on the side that comprehends things because I want to escape the anxiety of not knowing. I write my novels by building the plot first, and that also derives from fear. As of late, I find myself wanting to decrease my dislike of not knowing things. My awareness of not knowing served as one of the catalysts for me to write Seiyoku.

——I thought you were a very deliberate thinker when I read your past interviews.

Asai: Now, I think the source of my disposition comes from the fact that I thought the correct answer was in society.

I’ve lived my life being extremely worried about what other people thought since I was a kid. I used to believe that there was a fixed, unwavering answer outside of myself and that I had to adjust accordingly. I “tuned” myself so much. Obviously, though, society kept on changing.

Even as an adult, I was wary of what other people thought, and this feeling like “I need to be seen as a decent human being” and “I must be in the majority” controlled me.

When I worked at a company, I was caught in a trap because it wasn’t seen as a good thing to have a side job: “I can’t let others think I have another job.” Around eight years have passed since then, and today, having a side job is encouraged. I now finally realize that society fluctuates to a large extent, and I feel less restricted now.

Until this point, I used to write the world first and then the narrator second in my novels. Many of the story developments involved the narrator being agonized over the discrepancy between the world and themselves. I have an inkling I’m going to start writing in the opposite structure—the narrator comes first, and then the world comes second.

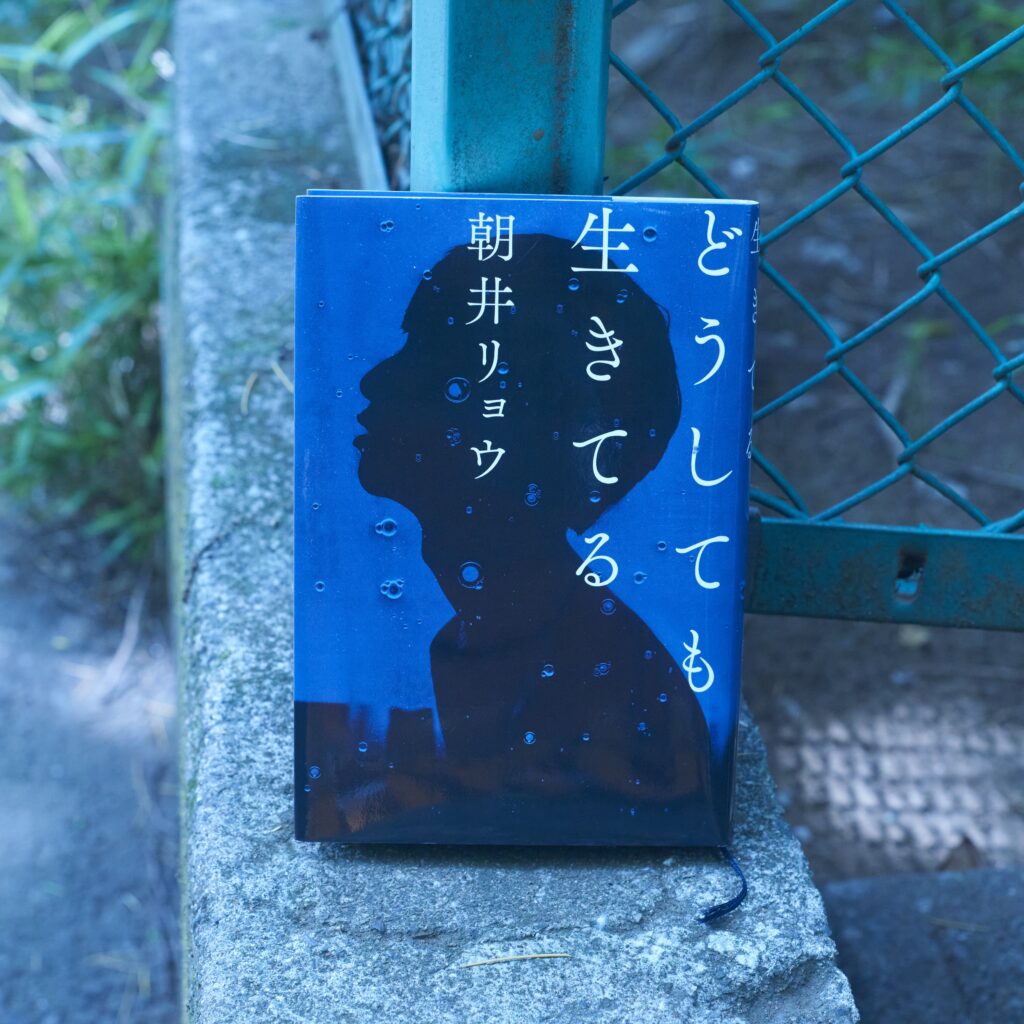

——I had the strong impression you were a writer who wrote about youth, but as can be seen in Shinigai wo Motomete Ikiteiru no, Doshitemo Ikiteru, and Seiyoku, the theme you write about has shifted to living life. How have your thoughts changed since your debut?

Asai: I still like novels about youth, and I reckon I’ll write more of them. When I made my debut, I was more desperate for a long time than now. I was like, “I need to be a popular [novelist] and survive.” I looked at things short term like, “If my next book doesn’t sell well, then I’m going to be left behind.” Also, because my debut novel received an entertainment award and my other ones received mainstream awards, I believed I had to write entertaining works that many people could relate to. I’m the type of person who suffers from the rules I make up on my own accord. I [told myself that] I shouldn’t leave the ending up to the reader because they paid for it and that I had to create works, which would let them forget reality and feel good because they paid for it. That troubled me. However, over the past few years, I’ve been able to go, “Anything goes.” So, I’d like to write whatever I please, including fun young adult novels.

——We see the conflict and questions towards society through your eyes in your novels. How do you search for such things?

Asai: I think of myself as someone who rewrites universal things that have been talked about to exhaustion in many places, using current words and things. There’s no such thing as a special kind of friction or doubt only I could find. It just so happens my job is to convert those into words.

The power of the novel lies in its ability to build a world that’s two steps ahead

——It’s now easier to communicate with words thanks to social media and messaging apps like LINE. You’ve also written a novel, Nanimono, where Twitter comes up. However, the tendency for people to attack others because of the normalization of social media stands out as of late. As someone who ruminates on language, what do you think about this phenomenon?

Asai: Whenever there’s a spotlight on online verbal attacks, you see an increase of discourse along the lines of, “Words can at times become a knife to hurt people. We must consider the way we use them.”

But verbal attacks are an accumulation of selected words meant to hurt the other person. Those who write verbal attacks know fully well that words could sometimes be a knife. They consciously choose strong words to hurt people. I feel like “thinking about how we use words” doesn’t get to the root of the issue. I want to confront our sadism and desire to hurt others, which we all have deep in our hearts.

Everyone knows hurting others is wrong or that words could at times hurt like a knife. But the feeling of wanting to hurt someone buds in everyone’s hearts at some point. It’s inevitable for one’s sadism to connect with words in one’s mind. That happens to me often. It’s essential to acknowledge that inner sadism, figure out how to tame it, and not act on it.

——It’s still scary to recognize our inner sadism.

Asai: I’m scared too. It makes me feel sick. The “you can’t verbally attack others. You can’t hurt others. Let’s learn how to use words in the age of social media” conversation seems like it’s one step forward. But I reckon it’s just a temporary solution. I think the whole “everyone has the potential to attack others verbally. How do we live with that?” conversation signals two steps forward.

Pointing to one step ahead shouldn’t be that hard. You can do that with marketing. But showing two steps forward is hard because you bring pain when you reject others’ efforts to move one step forward or propose another path from theirs. But the novel format can do that, which is one of its strengths.

There’s a law that bans outing someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity to a third party. But rather than striving to create a society where outing isn’t allowed, shouldn’t we aim to create a society where people of any background can live without changing anything and being deprived of things if they were outed? We need to take steps to get there, and it anguishes me to think this, but maybe the first step is to ban outing. What I’m talking about is purely idealistic, though, so it can’t save anyone who’s suffering right at this moment.

A new challenge to write something from a narrow view

——Every writer has a unique process. How do you write novels? Are you the type of person who comes up with meticulous character settings?

Asai: To be honest, I don’t know how I write novels. When I do interviews, I usually give a response that would satisfy the interviewer. There’s probably no consistency in my answers.

I can say that when I write a character, most of the time, I start by writing about those around them. If I were to write a character called A, I start by thinking about a character called B—someone close to them. What sort of person are they, and what sort of reaction do they have? I apologize in advance because I might be saying something completely different tomorrow.

——Do you craft the story in front of your computer?

Asai: When I type words on my computer, the story is already complete to a certain degree. I add words that would reproduce that the best. I come up with the story in my everyday life. The thoughts that have piled up in my head start to ferment and smell. And it’s like I turn that stench into a story.

——It seems like you’ve written a lot of your novels from personal experience.

Asai: People ask me about this frequently. It makes me feel down; my inept writing skills cause others to wonder whether my stories are from personal experience. I believe there’s no such thing as 100% fiction and 100% nonfiction. Let’s say there’s a line, “Good morning,” in a novel. My imagination wouldn’t have created those words, and that written real-life experience would include false memories. I don’t know if this will make sense but, if I were to write about the life of a woman ringleader of an American circus, people would think I wrote it from my imagination. If I were to write about a Japanese male writer of my age, people would think I wrote it from personal experience. But for me, both are equal strangers.

——This applies to Seiyoku as well. Many of your novels have multiple characters who narrate the story from their perspective. Do you do that because you don’t want to tell the story from one angle?

Asai: In terms of Seiyoku, the amount of information that could be withdrawn from one narrator in the first person is too limited. You can widen the scope the most with the third-person narrative.

I used to get worked up about expanding my horizons as a writer, so I could write a story that would resonate with anyone, anywhere.

Now, I want to challenge myself to write using each person’s extremely narrow view instead of expanding it. I want to prove that I wrote a story from such a point of view in this era. Even if it’s considered the worst perspective today, I want to leave it behind in history. It’ll be ideal if I could balance that challenge and the readers’ enjoyment.

Ryo Asai

Ryo Asai is a novelist born in 1989 in Gifu prefecture. In 2009, he published his first novel, Kirishima, Bukatsu Yamerutteyo, and won the 22nd Shosetsu Subaru New Writers Award. In 2013, he received the 148th Naoki Prize for Nanimono, and in 2014, he received the 29th Joji Tsubota Literature Prize for Sekai Chizu no Shitagaki. Apple selected Asai’s 2019 novel Doshitemo Ikiteru as one of the Best Fiction books on their Best of Books 2019 list. He has published Star and Seiyoku to celebrate the tenth anniversary of his writing career.

Twitter:@asai__ryo

Seiyoku

Author: Ryo Asai

Price: 1,870 yen

Publisher: Shinchosha

https://www.shinchosha.co.jp/seiyoku/

Photography Yohei Kichiraku

Translation Lena Grace Suda