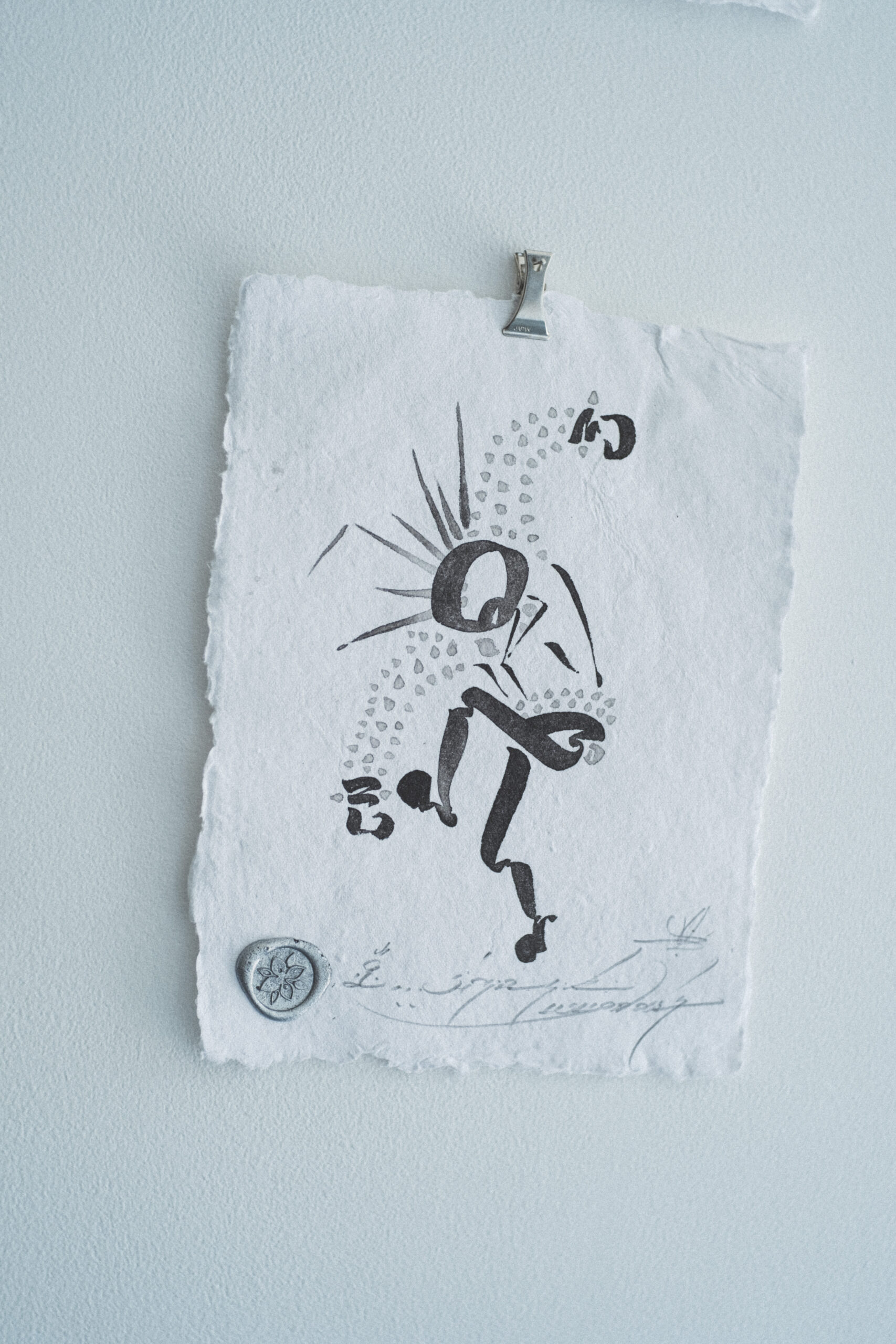

With his original “cosmopolitan” calligraphy comprised of fine dots and various alphabets, USUGROW draws a monochrome world. His intricate, beautiful works are beloved overseas, and every time he holds an exhibition, whether it’s in Japan or abroad, it makes a splash.

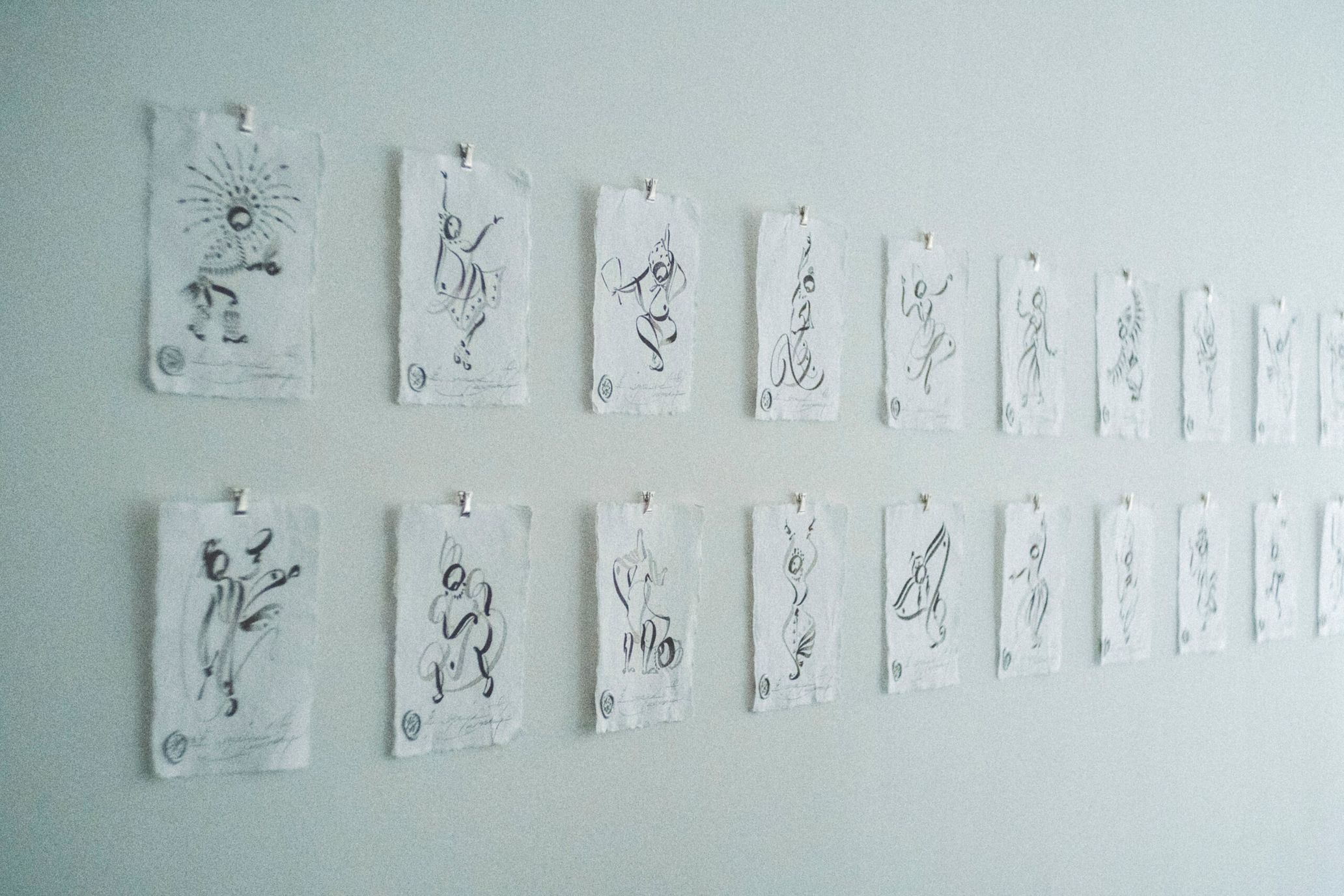

On June 25, along with artist imaone and architectural designer Ikue Nomura, USUGROW opened SHINTORA PRESS, a multi-purpose space in Minato-ku’s Toranomon, near Kasumigaseki and Shinbashi. As part of the grand opening, USUGROW held a solo exhibition in the space. In part 1, USUGROW talked to us about the thought behind the dance theme of his solo exhibition. In part 2, we unravel his past work and style while getting a closer look at the thoughts of an artist who is active around the world.

The meaning of “cosmopolitan” and his monotone universe

——When did you relocate your home base from Fukushima to Tokyo?

USUGROW: In 2000. I’d go to Tokyo every time I had a meeting, and even though I wasn’t planning to move to Tokyo, before I knew it, I’d moved here. (laughs) I was in a band in my hometown, but because I’d left it behind when I started living in Tokyo, I ended up commuting to Fukushima instead. (laughs)

——Has your monotone style stayed the same since then?

USUGROW: It hasn’t changed. It’s not that I absolutely refuse to use colors other than black and white. I want to use other colors, but I don’t know how to. For now, black and white are beautiful, so I just want to be able to use them properly. I want to use color when the time comes, so I do have green and blue just in case. Although they’ve completely dried up. (laughs)

——Do you like green and blue?

USUGROW: Yeah, I like them. Green like the leaves, and blue like the sky and ocean. I like purple, too.

——That’s great. I’d love to see your work in color!

USUGROW: It might be a while until then. (laughs)

——You’ve been drawing your original calligraphy, “cosmopolitan,” for a while, right?

USUGROW: Originally, cosmopolitan didn’t have any meaning, but I wanted my own font, so I started at the same time and in the same way that I started drawing. From the influence of tags in Venice [Beach] and Chicano-style cholo writing, as well as mixing the alphabets with elements of kanji and Siddham script, it [cosmopolitan] started taking shape. In 2008, I was given the opportunity to have a session with Chaz Bojórquez, and we talked about the importance of what we write with the letters. I started to simultaneously focus on the form of the letters while rethinking the message.

After that, I studied Arabic calligraphy and started Shakyo (a Japanese form of hand-copying sutras). At some point, the form of my letters and what I commonly experience abroad overlapped. When I would hear English abroad, I thought it was interesting to hear people whose native language is something other than English slip in and out of their accent. I felt a sense of harmony in people with different linguistic roots gathering in one city and using English to try and communicate with one another. I felt that my alphabet, which contains elements of many different writing systems, overlapped with that scene. Cosmopolitan means a world citizen or international person, so I feel that part of it relates to today’s ethos.

The moment when art transcends language barriers

——For you, music is part of your roots. You mentioned earlier that aside from hardcore punk and hip hop, you also like ethnic music. What kind of stuff do you like?

USUGROW: It’s hard to explain, but I like music that uses folk instruments but is made with a modern feel. Like having learned about the classics and history, and then doing a crossover with the present day. I’m striving for that feeling as well, and it resonates with me. But for example, that’s different from a rock band that says they’re conscious of Japanese style and just tops off the music with the shamisen sound.

——You also designed CDs and album covers for bands, right?

USUGROW: From 1990 until the beginning of the 2000s, I designed things like flyers, album covers, and merch for various bands. From 1997, I was going to LA every year, and I happened to become friends with someone who owned a record I drew the cover for, and I had my first solo exhibition abroad.

——Where did you have your first overseas solo exhibition?

USUGROW: A skateboard shop called Brooklyn Projects. At first, I happened to walk in by chance. One of the staff members was a guy in a band who liked Japanese hardcore, and he had a record that I drew the cover for. We became such good friends that he let me stay with him, and in 2006, I got the opportunity to have a solo exhibition in the shop. I’d just had my first-ever solo exhibition the year before in Sendai. I’d been thinking that I’d like to do one in LA and Tokyo next, so it was great that I could make it happen. After that, from 2007, I started having exhibitions in various places regularly, though mainly overseas.

——What do solo or group exhibitions mean to you?

USUGROW: I want to meet people I’ve never met before, and I want people who don’t know me to see my work. I try to keep my work open, so if someone gives me the opportunity, I want to do it at a large venue, but there are nice things about small galleries, too. But honestly, I have exhibitions because I want to have them at those particular places, I go to exhibitions because there are people there who I want to meet, and I cherish exhibitions because I like the scenery. That’s all there is to it.

——How was your first solo exhibition abroad? I think drawing and dance are both things that transcend language barriers.

USUGROW: Of course, I had that feeling, too. My roots are in underground music, and I’d always seen precedents of musicians who don’t get much media exposure in Japan but are active internationally, so I was happy to be able to have the first-hand experience of overcoming language barriers through my art.

——How did the visitors react?

USUGROW: I think they responded to the pointillism and the detailed handwork. Also, when it comes to adding things, subtracting them, or enjoying the white space—there might be a difference in sensibilities. I’ve been asked, “Why did you leave this space blank? You should draw letters or something here.” But I said, “It’s fine the way it is.” (laughs)

But that story is from the early 2000s, so I think it’s totally different now. Sensibilities get updated, and because we live in a time where we can connect across time zones, maybe the commonly used phrase, “national character,” isn’t that helpful anymore. I wonder how many people could actually answer the question, “What is a Japanese person?” I feel like it’s silly for your nationality to be your only point of pride. I think it’s more important for people to have confidence in themselves as individuals.

——The spirit of individuals, rather than the national character, is what transcends borders. That’s what led to your solo exhibition, SPIRIT BEYOND BORDERS, which we talked about in part 1.

USUGROW: At first, I thought it’d be easy to understand if I wrote the name of the dance and country on each piece. But I got stuck on writing the country name. For example, flamenco is said to have originated in the Andalucía region of Spain. But there was Arab influence there, and the Romani people who danced flamenco migrated west from India, so there’s a theory that it has roots in India’s kathak dance. Other than that, there are also many similarities in the costumes and movements of the dances of Southeast Asian countries, and with indigenous dances, there are similarities in the adornments they wear or their depictions of animals. There were a lot of similarities that couldn’t be categorized by country. Dance is something that people have passed down since ancient times, so it’s not the culture of a country, but the culture of people.

I think that the culture born out of expression can’t be categorized by country. I mentioned the phrase “national character” earlier, but I really want to say that essentially, people come before the country.

USUGROW(薄黒)

USUGROW is an artist who began his career in the early 90s making flyers in the underground punk and hardcore music scene. Since then, he has been involved in album design, art direction, and merchandise for musicians across various genres, and has collaborated with skateboarding and fashion brands.

Instagram:@usugrow

http://usugrow.com/

Photography Tsutomu Yabuuchi(TAKIBI)

Text Shogo Komatsu

Translation Aya Apton