The requirement for the film production was to document “a love story of a couple who lives together for decades.” In the beginning of 2019, Toda, who was contacted by an American producer, has subsequently went on a journey to meet couples all over Japan. She met some amazing couples, yet none of them approved to be filmed; as Toda was about to give up, through a series of fateful encounters, she eventually met Haruhei and Kinuko Ishiyama.

When Haruhei was in 6th grade, he had developed leprosy and was sent to a leprosarium, and there, he met Kinuko, who was working at the institution. One day, they had decided to “live like humans with the two of us together,” left the leprosarium as soon as they got married and started living in the housing complex in the outskirt of Tokyo, where they have been residing ever since for 50 years now. Haruhei has been going all over the country working to take action and share his own experiences with others, which has been his drive to live. On the other hand, Kinuko was living in fear of people broaching conversations about her husband’s illness and being discriminated or prejudged due to the disease, and always kept herself distant from others. However, Kinuko claimed the following and decided to put herself on camera: “I’m 99.9% ready to do this. We haven’t done anything wrong. I want people to know that we’re normal humans.”

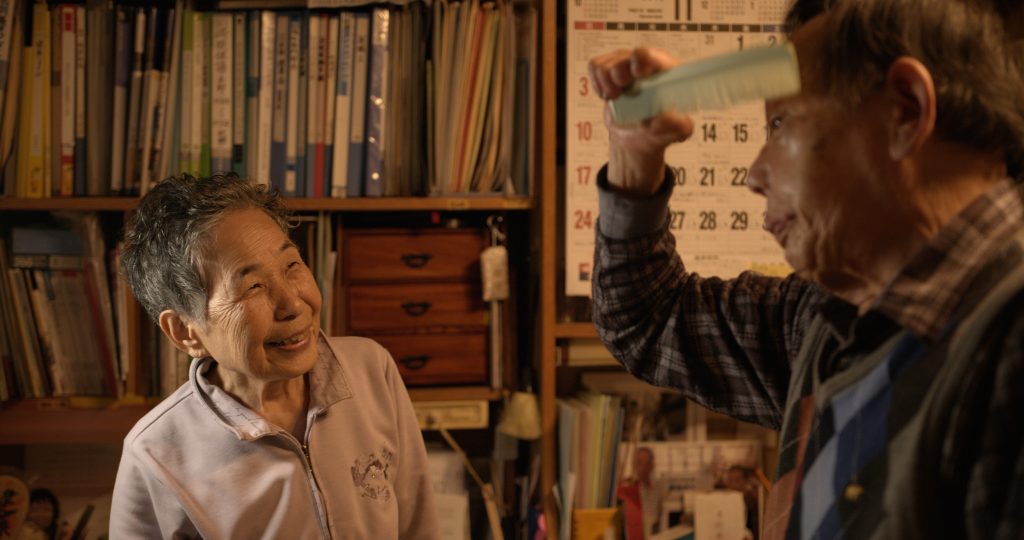

The Japanese episode shows the Japanese way of expressing love without verbally saying “I love you,” in which shows something beyond love exuding from the unspoken expressions. The viewers will feel as if they hear inaudible voices and see invisible love as they follow Kinuko’s tender gaze. In this article, we unveil Toda’s psyche, whose kind eyes have witnessed the couple’s life.

A film piece embodying the couple’s opulent sensibilities and ravishing human traits

――The film is now out on Netflix—how do you feel looking back on the days of the film shoot?

Hikaru Toda (from hereunder, Toda): I have always been making films that were to be premiered in theaters or film festivals, so it was a new challenge for me to produce a film on the premise of being streamed online. I’m eager to know who is watching and if the film is delivered properly to the targeted audience. Due to the pandemic, we currently don’t have a chance to meet new people, but in movie theaters, the subjects on screen and the audience get a chance to encounter and exchange energies with one another. I’ve profoundly realized that has been the source of my drive to live.

Before the outbreak of the coronavirus, Haruhei, despite his age of 85, has been strenuously going all over the country to give lectures on leprosy. He shares his rough past through his humor-infused talk, advocating for his comrades who have been floundering to raise their voices, as he has a strong will to eradicate the ongoing discrimination against people affected by leprosy.

On the other hand, Kinuko, as a family member of a recovered leprosy patient, has a past of living in fear of discrimination against leprosy and avoiding being seen for years and years.

However, since the court victory in the leprosy case for government reparations in 2001*1, Haruhei and Kinuko both gradually began opening their experiences to the public, which leads them to this day. It must have been an incredibly huge decision to make for them to appear in front of the camera having such past. When I met them, I found out that they have a past that they can only talk about and a side of their life that they can only show because it is now, which made me keen to document the couple living their lives in the present.

――During the 10 months of the shooting period, how did you deepen your relationship with the couple?

Toda: The shoot started pretty soon after our first time meeting the couple, so we, the film crew, built the relationship with the couple during the shoot. In the beginning, we were strangers, and I’m sure there were various filters in how we see one another. We had to take away each filter one by one and required some time to become capable of facing one another as an individual. In order for me to tear off the couple’s label of “recovered leprosy patient and his family member” from my mind and rather face them as “Mr.Haruhei” and “Ms.Kinuko,” I had to study about the history of leprosy. The couple gracefully welcomed us like we were their grandchildren and treated us equally. During the shoot, we exerted all our efforts to respond to their generosity and expansive hearts.

Throughout the seasons, as we filmed the couple living everyday graciously, we were able to sequence the scenes pretty much chronologically. In the beginning, there are moments where the couple looks endearingly awkward as they are not used to the camera, but toward the end, I think the viewers can perceive the rapport established between the couple and us, the staff.

Regarding documentaries, our relationship with the cast is what makes the moments captured on camera. Normally, we would require a bit more time for shooting, but due to the fixed timeline and the pandemic, the shoot had to be wrapped up by the time we got used to one another. Yet, I think all the times we had shared together off camera, like having tea and eating together, are successfully mirrored in the scenes.

Understanding one another’s strengths and vulnerabilities, and facing one another as an individual

――What part about them were you especially attracted to?

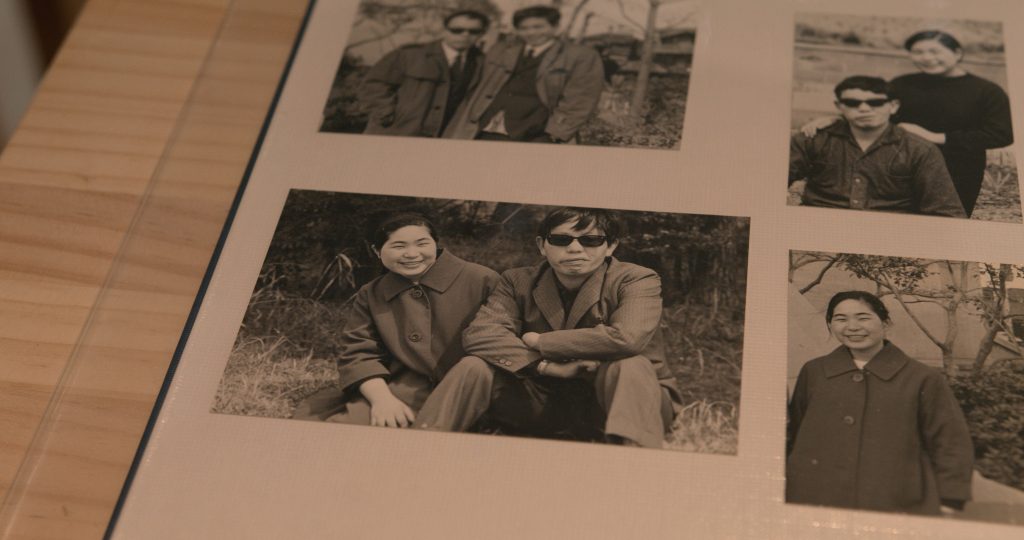

Toda: First of all, I was enchanted by the couple’s characters. Haruhei takes many photos since he was in leprosarium and Kinuko avidly writes tanka, which she calls the collection “document of life”; I was very intrigued by the couple who are both expressionists.

In leprosariums, patients were forced to go into quarantine, and as a means for them to connect with the outer world, cultural activities have flourished and literature, music, written materials, tanka were among the many art mediums. When Haruhei was in the sanatorium, he learned how to write letters and started taking photos. Kinuko was helping him develop the photos in the darkroom, and they say, that’s when “love kindled” within them.

Haruhei lightened the mood by telling us punning jokes and Kinuko added witty responses; they were always entertaining us with their comical interactions. They were absolutely caring about us a lot.

Moreover, I’ve learned a lot from their stance of accepting each other’s vulnerabilities and pasts, as well as confronting themselves in the present.

――Were there scenes that were inevitably cut?

Toda: We filmed Kinuko writing a letter and putting it in a post box, and she was enjoying the many adventures spawned from the brief journey. She would find surprises from gazing fondly at grass and trees or talking to birds, and cherish small, beautiful things that we wouldn’t normally care to look at; unfortunately, we had to cut most of these moments for length issues when editing, but we were able to put a small bit in the end as a very symbolic scene. Kinuko is genuinely a cute woman with an innocent heart of a young girl, so we secretly call her “forever young girl, Ms.Kinuko.” I want to be a generous person, who is kind and warm-hearted like Kinuko and Haruhei.

――As subjects to film, what kind of people are you attracted to?

Toda: I’m attracted to those who can accept themselves and others as “individuals.” “Facing someone as another individual” is easier said than done, and I’m constantly concerned that we may be only seeing one another by our positions or attributes, and question myself, wondering if I’m facing people as an individual or not.

For my previous film, Of Love & Law, I’d learned about the statelessness issue*2, and it was a revelation to me that how in Japan, you aren’t deemed an individual if you’re refused to be accepted as a family member. Through this issue, I was finally able to see the basis of the discomfort and dubiety that I’ve been feeling since I moved to Japan toward the fact that the simple act of claiming yourself as an individual may lead to various perils in the society and with the law where individuals aren’t respected.

I had lived in Holland from when I was 10, and until 6 years ago I was living in London, and since I’ve experienced being categorized as “a Japanese” or “an Asian woman,” I’ve always been interested in identity issues.

The society will not get better until we overcome our sense of discrimination

――You’ve moved to Osaka to film Of Love & Law, and I heard you still live there.

Toda: I’d always been strongly aware of myself as a foreigner and that I was an “outsider” or “minority,” but now that it’s been 6 years since I moved from London to Osaka, and as I’m a Japanese living in Japan, able-bodied and cis gender, my consciousness of my identity on the majority side has really been raised. And I’ve started thinking even deeper about this matter since I’ve encountered the issues relating to leprosy through the shoot of My Love.

Even out of the entire history of leprosy in the world, the quarantine measure that lasted for nearly 90 years in Japan is exceptional. The unethical policy has led false information percolate through the society, and that deep rooted implicit discrimination has become indelible that it exists even to this day. Someone like Haruhei, who has rehabilitated back into society and can talk about the past experiences, is quite rare, and most people who have suffered from the disease or live with a family member who has been through the illness, live over decades without being able to open up about it.

Documentaries are inclined to rely too much on the courage of the person in front of the camera. But the filmed images that show things that are visible can also convey things that are invisible. So, I think it depends on the “viewers’” point of view whether they can put their imaginations to work to perceive from the film that there is a mass of people out there who cannot raise their voices.

Whether I’m going to send kind regards or give suspicious looks to strangers—I think each and every one of us needs to pay heed to and proactively confront the implicit discrimination that resides in our subconscious minds. Especially since the opportunities to meet people have dwindled due to the spread of coronavirus, it seems like people are casting a sterner eye over things unknown to them.

Like the way I was able to discover from making this film, I hope this documentary gives viewers an opportunity to realize that our current situation lies in the extent of the past history.

――What do you think about the fact that there are a lot of people living uneasily in the current circumstance?

Toda: While due to Covid, I feel that the things that are essentially hard to perceive in this society have become even harder to see, and on the other hand, the things that were tacitly condoned have become visible—such as matters like rich-poor divisions and dishonesty of politicians. Because of the ongoing “self-quarantine” and business suspension without adequate financial aid, there are a lot of people who have reached their patience and are anguishing with their lives, which shows that the distorted society takes a toll on the people who are in weak position. I’m sure there are a lot of people who are suffering out of the sight of the world, in this society, where people can’t even ask for help with words like “self-help” and “self-responsibility.”

The Japanese movie industry is also continuously in a rough situation, and movie theaters are in peril. Such places, where diverse people gather and that showcase us new worlds, need to be saved or else people’s perspectives will be narrowed, and people will eventually lose their imaginations.

I think it’s now especially crucial to keep an eye on misconducts by politicians, keep our imaginations alive, and give warm regards to the things that are hard to see.

*1. Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae. It is less infectious and can be cured with no after-effect by early treatment. In the old days when there were no effective treatments, the illness was said to be incurable, a divine punishment, and a curse, and the leprosy patients were ostracized from their hometowns and forced to isolate themselves. In Japan, until the Leprosy Prevention Law was enacted in 1996, the compulsory quarantine measure was forced on leprosy patients for nearly 90 years. In 1998, the recovered leprosy patients have claimed that the compulsory quarantine measure violates the basic human rights stipulated in the Japanese constitution and filed a lawsuit against the government for reparations on the breach of the constitution. In 2001, the plaintiffs won the case at the Kumamoto district court and the government admitted its responsibility. In 2019, the plaintiff of the “leprosy family case” had also won court victory, which elucidated that the quarantine measure had exacerbated prejudice and discrimination towards the former leprosy patients and harmed their families’ relationships, and furthermore, the judgement pointed out that the public was also responsible for the matter.

*2. The Statelessness Issue occurs when, for certain reasons, the birth registration has not been submitted or officially accepted. The biggest cause of the issue is said to come from the civil law that remains in effect since the Meiji era, which stipulates that “a baby born to a woman within 300 days of her divorce must be regarded as having been fathered by her former husband,” and the law applies even if a woman has a baby with a man who is not her husband, in which case the baby will be registered on paper as a family of her legal husband; it is said that there are over 10 thousand “stateless people” in Japan, whose birth registrations have not been submitted due to issues such as domestic violence.

Hikaru Toda

Hikaru Toda grew up in the Netherlands from the age of 10. She studied social psychology at Utrecht University, and visual anthropology and performance art at the Graduate School of the University of London. She had been based out of London for 10 years making footages all over the world. 6 years ago, she came back to Japan after 22 years of her life abroad, to produce the film Of Love & Law. For the film, she won the Japanese Cinema Splash Award at the 30th Tokyo International Film Festival, and Documentary Competition Grand Prize at Hong Kong International Film Festival. She currently lives in Osaka.