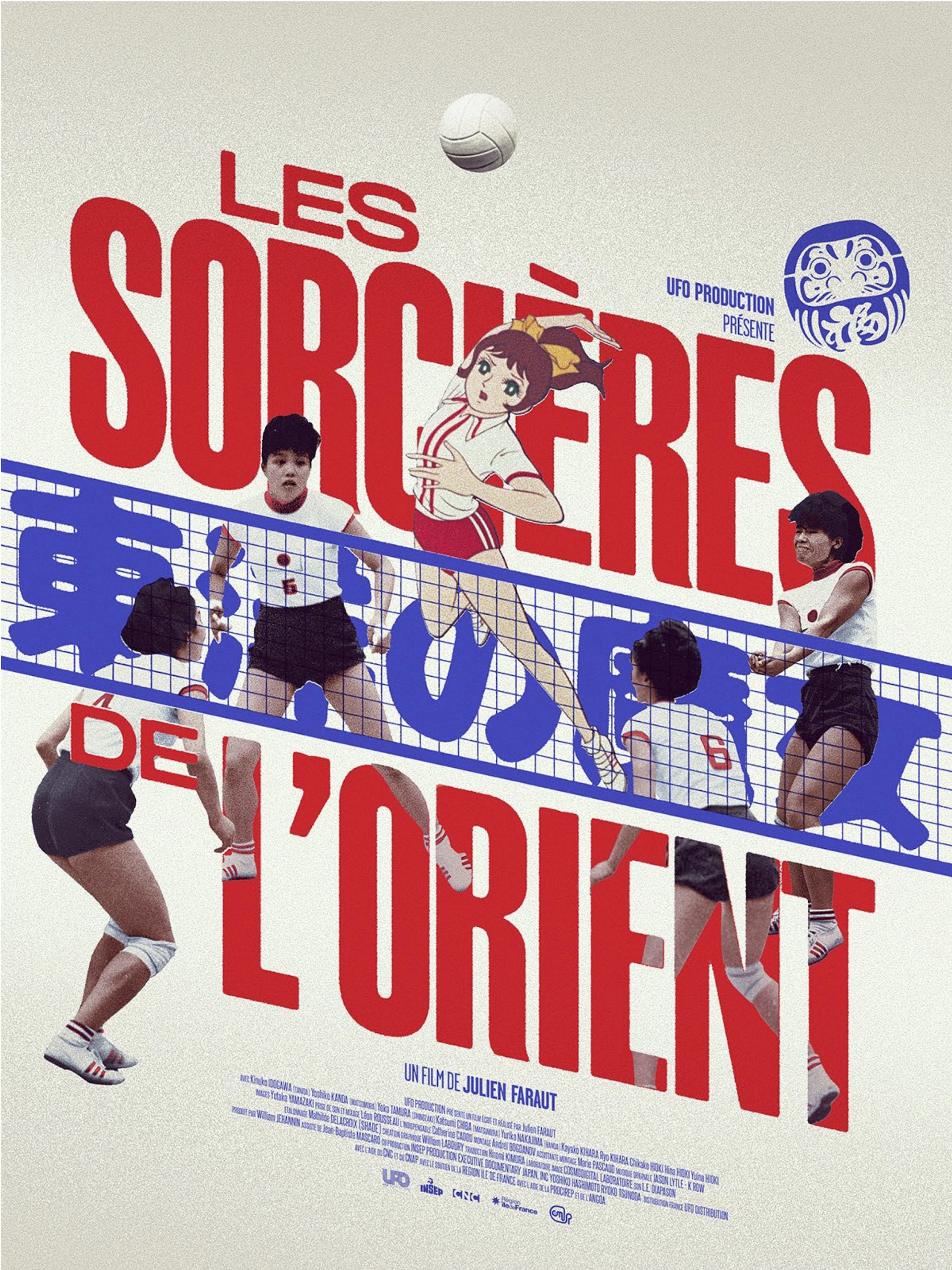

Years ago, Julien Faraut, who works for the National Institute of Sport in France, was shown a 16mm footage of the Japanese women’s volleyball team from the 60s. The team, which consisted of workers from a textile factory took the world by storm by winning a series of high-profile games in Europe and achieved an almost mystic status, enough to be named the “Witches of the Orient.” Faraut was struck by the intensity of the training, which eventually led him to create a documentary about the players and their saga to stardom.

The documentary, which took three years to complete, is a confluence of training footage, anime and electro music, but the highlight is, nonetheless, the interviews with the “witches”, now in their 70s and 80s. They endured unimaginably hard and torturous training, and yet their sense of selflessness is still reflected by the way Faraut described them, “They are truly humble.” I asked Faraut about the influence of anime in his work, the experience of traveling to Japan to interview the “witches”, and his thoughts on the cultural differences in the training approaches for sports.

Very unfortunately, one of the featured players of this documentary, Mrs. Tanida (current surname, Idogawa), had passed away last December. She had been selected as one of the torchbearers in Osaka Prefecture for the Tokyo Olympics 2021. The film is scheduled to premiere in Japan this summer.

I was stunned by the sequence of the training.

――I heard that you saw the first Japanese anime broadcasted in France and also watched Attacker You! during your childhood in the 80s. Can you share your early memories of Japanese anime? What did you find attractive about anime and Japanese culture overall?

Faraut: I was born in 1978. Growing up in the early 80s, we experienced a big wave of Japanese anime on French TV although we didn’t know at that time that most anime came from Japan. In France, people first discovered anime and later learned that they were based on manga. In the 90s and the 2000s, animated films by Ghibli became famous, and people really loved Miyazaki and Takahata. We lived in a time that our choice was limited. We felt that anime was new at that time. There is a generation in France which grew up with anime and shared similar cultural aesthetics because of that. We were watching anime made in the 60s and 70s in Japan, a decade later in the 80s. Although there was a delay —some of the anime were old—it was considered new and fresh in France.

――I know that a trainer brought you footage of women’s Japanese volleyball. Which parts of the footage exactly inspired you to decide to make a film?

Faraut: When I saw the footage of the Japanese volleyball team, I was stunned by the sequence of the training. It looked contemporary and featured high-level athletes. I really liked the intensity of the training, and the speed of the drills. It certainly reminded me of the anime Attacker You! which was very popular in France. The footage became the starting point of the project, but I was not sure if I could make a documentary. Then, I saw The Price of Victory by Nobuko Shibuya, which won the Short Film Palme D’or in 1964. The film footage was colorful and beautiful, and I was convinced that I had enough material to move forward with the project.

―― How did you get in touch with the players, who are featured in the documentary?

Faraut: I went to Japan for 10 days in June 2019 and visited four players in Kansai and Kanto area. I wanted to get in touch with all of the players, but two have already passed away. I ended up meeting Yoshiko Matsumura, Yoko Shinozaki, Kinuko Tanida, Katsumi Matsumura, and Yuriko Handa and spent three to four hours with each of them, except Handa-san, who agreed to join the lunch with other players. Since I don’t speak Japanese, I visited them with an interpreter. Her name is Catherine Cadou. When I interviewed them, I just put a recording device on the table and decided against using a lapel microphone as I wanted to be polite and not intrusive.

After returning to France, Catherine translated the interviews, and I chose the parts I wanted to incorporate in the documentary. I decided to tell the story in a chronological way from their days at the textile factory, winning the World Championship, and eventually the Olympic Gold Medal. In October 2019, we returned to Japan to film the players. Although I had some ideas about how to match the excerpts of the interviews that I chose and the shooting location, I asked each of them if they had preference about where they want to be filmed.

Matsumura-san wanted us to film her at the gym where she practiced every week. That was her fitness routine. She was in good shape and showed us her muscle. Shinozaki-san is still playing volleyball and trains a women’s volleyball team. We filmed her at the training session. Tanida-san and the other Matsumura (Katsumi)-san were not clear about their preference. Tanida-san was living with her daughter and grandchildren at that time and I suggested filming her at home. She said that she liked to play games with her grandchildren. In fact, I brought a memory game and ended up shooting a scene of them playing the game together. Matsumura-san was different in terms of her behavior and character. She was blunt and basically said that she would do whatever we asked her to do. We ended up shooting her in a bus.

We went to Japan twice. The shooting was short as we spent only a day with each player. Due to budgetary constraints, we needed to be quick and efficient. I also didn’t want to bother the players too much.

Daimatsu’s view was both conservative and open-minded.

――The way Japanese train their athletes in sports team, which emphasizes the relationship between master and student, is very different from the Western culture methods. What are your thoughts on the Japanese approach versus the Western culture approach?

Faraut: The pertaining culture is different so the training method also reflects that. I used to practice judo, and I was aware of the Japanese customs in terms of training. In Japan, there is constant reference to Bushido, and it’s a real discipline. In France, it’s not about the master and the disciple; it’s about the teacher and the student. We came up with a pedagogy — a way to teach.

In Japan, you just practice blindly and master the move through repetition. Then you can reflect on what you are doing. It’s a different way of training. I learned that the Westerners were shocked by Coach Daimatsu’s method and the training routine of the team. I think there was a cultural misunderstanding and gap. The Westerners speak about women’s freedom, while women are considered inferior to men. In Europe, women gained more freedom, but the mainstream opinion was that women didn’t have to hurt themselves to train for sports because they were women. Then, they faced a women’s team from Japan that trained excessively and even hurt themselves. Japan is a patriarchal society, but Daimatsu also said that he would train the women like men. This view was both conservative and open-minded. I was intrigued with the complexity of his thinking. The intensity of Daimatsu’s training method was unparalleled in those days. But, now every woman in high-level sports train as hard as men or sometimes more than men. This was one of the big reasons to make the film. I wanted to show how different the Japanese training was. The Japanese way was — just do it, don’t question it, and master it. In France, the training is more cognitive, with a constant need for understanding what you do and why you do that.

I also thought that people are more receptive of their roles in Japan. If they are told that they are the substitutes, they don’t question the decision or argue about it. That would be different in France. If you enlist one of the best players to play for a national team, they won’t tolerate being on the bench. If you tell them that they are a substitute, they will question that decision. I thought that’s one of the main cultural difference among the players.

They trusted him and decided to follow him.

――How would you expect the audience to react to the film?

Faraut: I think the audience in general does not know much about high-level sports. I think the Japan vs the West concept is more of a secondary aspect. What pleases me about the Japanese volleyball team is that these women were pioneers. They accepted that if they wanted to be the best player of the world, they had to train much more than they had been used to. The audience will discover the reality of high-level sports in Japan, which was organized by companies in those days. The volleyball teams were closely linked to the textile industry. For example, in France, there is a sports ministry, which organizes sports in this country. In the U.S., high-level sports are organized at universities.

I also hope that the film will help the audience understand that Daimatsu was not a demon and that those players were not abused or forced to do things they didn’t want to do. That was the reason I wanted to get their testimony. I want them to tell us their point of view. When I found out that Shinozaki-san was still playing volleyball at the age of 74, I thought that it was not a painful experience for her to be trained under Daimatsu. If that was the case, she would have never played volleyball afterwards. I think they were all passionate about volleyball. They were not ordinary women. They were very strong. They were witches and they really had some super power. They chose to follow Daimatsu as he was the perfect man for them to become the best players in the world. They trusted him and decided to follow him. It was their decision.

―― What was your most memorable scene and why?

Faraut: There are two memorable moments. When all the players were having lunch, one of them tricked the others and made them believe that she was drinking alcohol although it was just water. When they found out, they all laughed out loud. I felt that they used to laugh together the same way as when they were young. It was a spontaneous and genuine moment. I was very touched by this scene, and it still brings tears to my eyes when I watch it.

The other one is the image of Daimatsu right after the victory of the Olympic final. There is a close up of him on the bench, and he didn’t move at all. He had tears in his eyes and, maybe, he didn’t want anyone to notice it. I was very interested in this moment. He could have been joyous. Then, I understood that the victory meant the end of a long journey for him —he was going to lose the players. They reached the goal and the players will move on. I think he felt a mix of happiness and sadness.

―― The way you edited the animation and electronic music were outstanding, as well as integrating Portishead’s Machine Gun’s music into the documentary. You also collaborated with Jason Lytle on the music. What was your inspiration to utilize these types of animation and music for the documentary?

Faraut: The training footage and the anime are very similar when you look at the frames. I didn’t have enough footage to depict the finals of the World Championship and the Olympics final. The anime was used to fill in the gaps out of practical needs.

When I was editing the footage, I was looking for music or sound with the right rhythm to create a third dimension. Back then, Portishead released their third album, and I thought that one of the songs was a perfect fit for the footage. I also thought the retro synthesizer was very Japanese. I am a fan of vintage synth, especially the ones made in Japan. In fact, I got a vintage synth in Japan and used it to make the ending music. Jason Lytles made music for the scene when the team won the Olympics final. I think it’s a perfect match to the moment when Daimatsu looked melancholic.

I felt that Japan in the 60s was very futuristic when Japan became a pioneer for new electronics. For me, the 60s in Japan is the past image of the future and that inspired me to incorporate retro futuristic music to the film.

――From making this documentary, did you discover anything new about the Japanese culture that you did not know before?

Faraut: I discovered how truly humble these Japanese women were. I would tell them what they had achieved was not normal, and they were very strong and special. And they would keep on saying that it was nothing special. They were not pretending to be humble. In the process of translating the interviews, I also learned from Catherine about the complexity and subtleties of the Japanese language. I have to tell you that something beautiful happened during the interviews. I don’t speak a word of Japanese, but there were many instances when I told Catherine not to translate as I already understood what they were saying. It was magic. In many cases, I got the meaning right. I could understand them by the way they were talking and from their gestures. It happened many times. Maybe because I knew the subject well and tried my best to understand them.

――It was impressive to see the players opening up and talking about so many things. Japan is a collectivistic culture especially their generation. In general, Japanese people aren’t comfortable with being in the spotlight, and talking about themselves with confidence. How did you approach them and get them to open up?

Faraut: I thought I was facing a generation gap as I am 42 and the youngest player in the documentary is 73. Then, I found Catherine to help out the project as an interpreter. She is 74 and is the same generation as the players. I thought the issue of generation gap was solved thanks to her presence. Catherine is well-known in France for her work in Japanese cinema. She worked with Akira Kurosawa in the 80s and knows many Japanese directors and actors. She attended the Olympic games as she lived in Japan for many years. I asked her to get in touch with the players to let them know about the film project. Catherine started to communicate with them via mails and phone calls and cultivated a relationship with them. I remember asking Catherine how we could approach them in a gentle and proper way. The last day of the shooting was at Katsumi Matsumura’s home, and we were packing our bags. I saw Catherine holding hands with Matsumura-san like good old friends. When Catherine traveled to Japan, she visited some of the players again. She became close to them. My goal was to pay tribute to their achievement. I am very grateful for Catherine, and I hope we didn’t ask the players too much.

Julien Faraut

Having worked with the French Sports Institute (INSEP) for 15 years, Julien has had access to a large and mostly unseen collection of 16mm archival footage. With a fascination for the incredible achievements of highly skilled athletes, Julien’s portfolio of work explores these unique and astonishing human beings through the medium of film, aiming to bridge the connections between sport, cinema and art.

Picture Provided UFO Production

Translation Fumiko M