Fifty years ago, Nik Cohn wrote the first great text on men’s fashion. Today There Are No Gentlemen— which took its title from a line offered by a dejected cobbler— brilliantly illuminated changes in the clothing of English men after the second world war. Last autumn, Today There Are No Gentlemen returned to bookshelves for the first time ever since its publication— in Japan, exclusively. W. David Marx, who wrote Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, was the driving force behind the new life of Gentlemen, yet he had never spoken to Cohn. In the first part of their conversation together, they discussed the conception of Today There Are No Gentlemen and its new Japanese translation, alongside obscured subtexts and histories running concurrent to the book. This second part of the interview brings the decades following Gentlemen to light, with new reflections from Marx and Cohn on the nature of culture and its transitions.

Right: David Marx

Right: Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style

Speeding cultural changes in music and fashion

David Marx: In the book, you’re cataloguing perhaps the fastest cultural change ever in human history. I find that interesting right now because there’s been this dialogue over the last decade that there’s been no cultural change, that things are really slowing down. I’ve kind of come to the conclusion after reading your book that the ‘60s are the exception rather than the rule — and that’s not a pace of cultural change that humans can probably follow all the time. In the moment, was that obvious, or is it only obvious in hindsight that the change was so much and so fast?

Nik Cohn: Hindsight. At the time, it seemed almost automatic. That’s partly because it was so fueled by drugs, and therefore things that would otherwise seem extraordinary felt normal…but quickly it changed. I’ve said this elsewhere, somewhere, but: if you had said to a singer in an upcoming band in 1964, “you know, you’re a serious artist,” they would have thought you were taking the piss; they might easily have punched you out. Whereas, by 1967, if you had said to the next wave of singers, “you know, you’re not a serious artist,” they would be shocked and dismiss you as a total philistine. It took only two or three years to go from the idea that pop music was just a business to the idea that it was an art form. And I think if you go to fashion, you see more or less the same thing. Of course in the end, the driving force in both cases was money.

Marx: If you show me a film from the ‘60s, I can probably tell you what year it is, just by the grain of the film, the colors, and what people are wearing. But you can’t do that any more…if you show me a film from 2002, it’s very difficult to know that it’s from 2002.

Cohn: Yes, I think that’s true. In the ‘60s and the ‘70s, all the way through to a group like the Clash, it was very important to be specific, to say, for instance, ‘We are West London, it’s 1979, we dress this way, our fans look that way, we hang out in these streets and clubs,’ in other words to nail down the exact moment. That isn’t a key any more; culture is much more homogenized. If something comes up from the streets or out of someone’s bedroom, it’s spotted instantly and mass-commodified. The first thing that happens is to take away the thing that made it specific to one place and one moment. In the ‘60s that didn’t happen. Where you came from, and the forces that had shaped out, you never let those go.

Marx: The book came out in ’71, and right after that there was a teddy boy revival in the U.K, and you soon get punk rock, neither of which were covered in the book. What did you think of those at the time?

Cohn: Oh, I didn’t take the teddy boy revival as serious, or being real; it seemed to me more of a marketing concept than something anyone believed in. But I took punk very seriously indeed. In many ways, it seemed to me the most authentic street movement of all, at least until hip-hop came along.

Punk, the ‘70s, and subcultural shifts

Marx: Did Malcolm McLaren feel like one of those ‘60s clothing entrepreneurs [in your book], or did he seem new?

Cohn: He seemed authentic, in a completely fake way. I didn’t know him personally, but he clearly was a spirit for the good, a risk-taker, and he grabbed onto something in rather the same way that Andrew Oldham grabbed onto the Stones in the ‘60s. He was able to capture something in the air early on, and take risks. He wasn’t scared of a risk at all. So I approved of him, very much so.

— I read recently that in his last years, Malcolm McLaren had gone on record to say that it was Today There Are No Gentlemen that led him to create the first iteration of his shop on King’s Road. In terms of that domino line, that’s a pretty significant moment in history, I would say…

Cohn: [laughs]

— But I wanted to ask you, David, Malcolm McLaren became a major figure shortly after Today There Are No Gentlemen, but also he appears at least twice in your book, Ametora, first with Cream Soda and Masayuki Yamazaki, and then again in the early ‘80s, when Hiroshi Fujiwara visits McLaren…

Marx: Yes, there’s a direct through-line. Malcolm McLaren’s store was called Let it Rock at some point, and then it was Too Fast To Live, Too Young To Die. The latter became the slogan for the first Japanese rock’n’roll store, Cream Soda. The guy who started it, Masayuki Yamazaki, had gone to London in about ’74-’75, and went to McLaren’s shops. He even had a punk fashion store in Harajuku called Super Sex modeled on the SEX boutique, McLaren had a heavy influence over Japanese youth culture. The Harajuku neighborhood, which is kind of like the Carnaby Street of Tokyo, really begins as a youth culture neighborhood with the Cream Soda store. And then Hiroshi Fujiwara, who went on to become the godfather of street fashion in the 90s, had discovered hip-hop early. He was very into Seditionaries and went to go visit London, and McLaren told him don’t be into punk, be into hip-hop, hip-hop is the new punk. And so he visited New York and became a bridge between Japan and NY-London street culture.

In the new book I’m working on, I’m trying to take a step back from these individual histories and think about the “rules” of how cultural change happens. There appear to be laws, almost like gravity, that determine the way these movements rise and call. And what is clear, in Nik’s book, is that you see the exact rhythm in which it happens. Each movement is trying to mark out its own space to be rebellious; it gets co-opted, and then obviously, in the co-optation and commercialization, loses its ability to mark difference. This then encourages the next group to rebel against the previous movement as hard as possible. You see this in the transition from fancy mods to skinheads. What’s important is that none of these phenomena are isolated: they’re always an exaggeration or a negation of the previous thing. This cultural evolution never happens in a vacuum — it’s always in relation to the thing before.

Cohn: Yes, I think that’s very true. Except with one caveat— that the rebellion against the previous thing, at the time, seems as if you were going to the opposite extreme. But then you look back, and you realize it isn’t new after all. At the deeper level, what you have is one generation after another, saying the same thing, which is ‘I am me, and I am one of a kind.’ And the moment they say that, they’re actually dooming themselves to repeat the past. The trappings and slogans are different, but the underlying impulse is eternal.

A couple of years ago, a woman from Northern Ireland approached me and wanted to do a film about my life. I asked her how she’d come to me as a subject, and she said she’d been in Japan, doing a documentary about Japanese mods and she’d asked them why there was no great mod film. And they said, “You’re wrong, there was one great mod film: Saturday Night Fever.” Well obviously, they knew the difference between disco and mod, but they saw the inner connection.

Marx: Because the underlying motivation for what they’re trying to do with fashion is the same, but in order to express difference it always has to be in context of the thing that goes before it.

Cohn: That’s right, yes. It’s almost like the Freudian thing, you have to kill the father to be the father.

— David, Nik has this moment in Today There Are No Gentlemen where he shows a pure fascination and attraction to the musician’s window in Cecil Gee’s store— “the most splendorous sights that I’d seen in my life: danceband uniforms of lamé or silk or satin, all tinselled and starred, a shimmering mass of maroons and golds and purples, silvers and pure sky-blues, like fireworks.” My understanding is that this moment, in 1957, is essential to him in terms of what he later becomes entrenched with in London, in music and fashion and everything else. Your book, Ametora, covers such a wide range of styles, and I was wondering if personally, for you, there have been comparable moments that sparked this need to document what you saw.

Marx: I grew up mostly in Pensacola, Florida, which is not small enough to be a small town, but not big enough to be somewhere, and pretty far from other big cities. So there was no moment of going somewhere physical [like Cecil Gee’s store]. For me, my window was MTV. Also I had a much older brother and sister who were into very cool bands…I grew up knowing REM and U2, while most people were into hair metal. I developed a very early snobbery about music. Fashion, on the other hand, felt incredibly far away from me.

In America, at that time, clothing was t-shirts, sneakers, shorts, jeans; you bought it for $20 at the Gap. The life-changing moment for me was coming to Tokyo at age 19, and Tokyo just being the most immaculately fashionable city I’d ever seen — without any warning. Nobody told me “Oh, you’ll be blown away by how fashionable everyone is in Tokyo.”

In fact, there was a lot of American writing at the time about how uncool Japanese kids were. Then I got there, and everyone was wearing t-shirts, jeans, sneakers, but they were wearing the perfect t-shirt, the perfect jeans: a $70, limited edition t-shirt, with $300 limited edition selvedge denim, with the cuffs rolled up so that you could see that it was selvedge, vintage Adidas superstars that nobody was wearing in the U.S. That was my introduction to fashion, because I could see myself being “into fashion” if fashion was a better version of the clothing I already wore. When I was in Tokyo, I waited in line for three hours to buy a t-shirt. Three hours: every time I say that, it sounds like some sort of exaggeration, like it’s hyperbole, but it was literally three hours waiting in line to buy a single t-shirt. Then I went up the street and I saw all the same T-shirts for sale for double the price: the resale market was starting then too.

That experience made me not just be interested in clothing on a personal level, but also made me interested in it as a sociological topic. Why in the world would somebody wait three hours to buy a t-shirt? All of these things now, you know, with Supreme, have become global…but at the time it was really a Japan-only phenomenon. And I had to go to Tokyo to get a view of it.

Nik Cohn

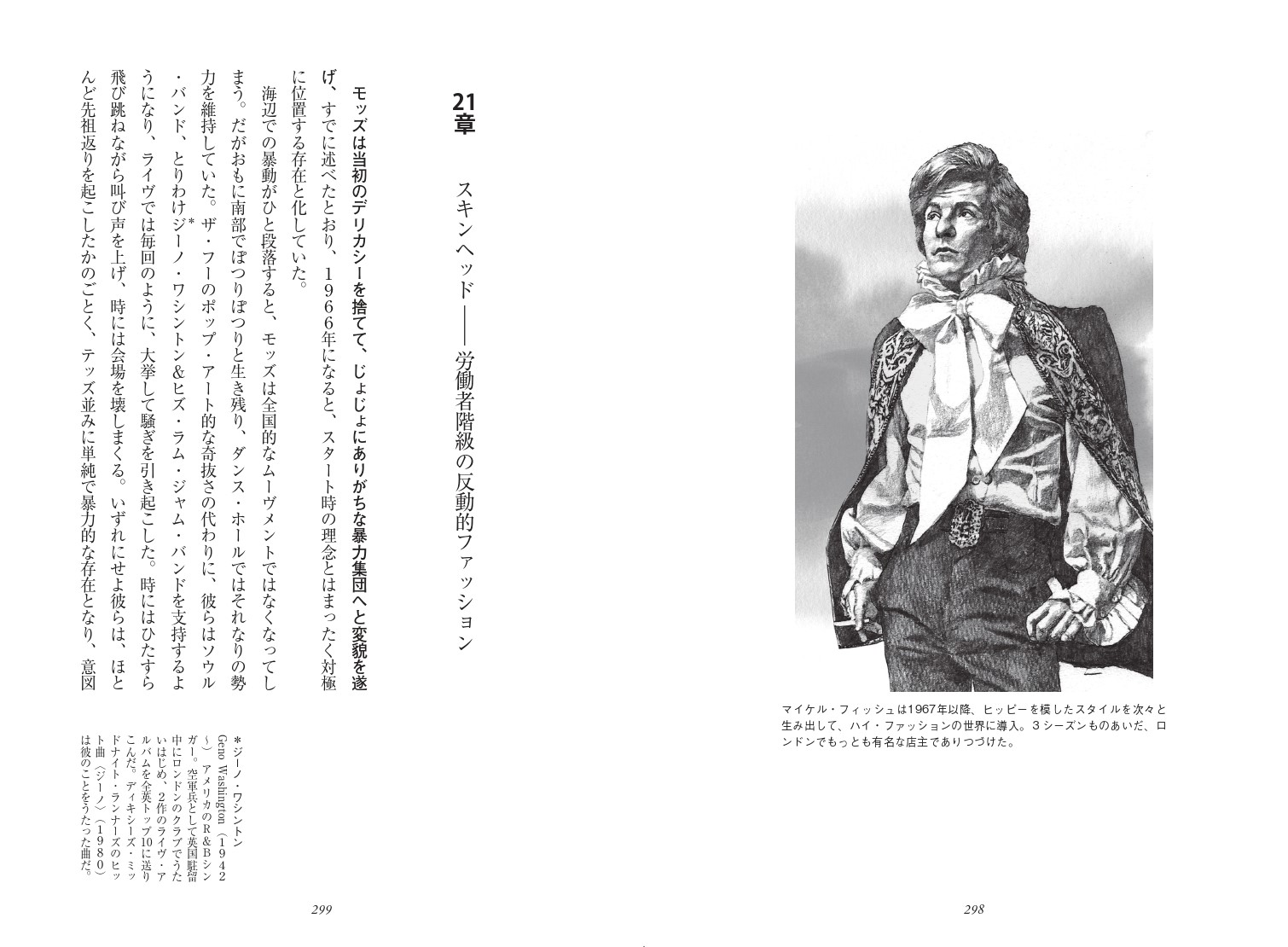

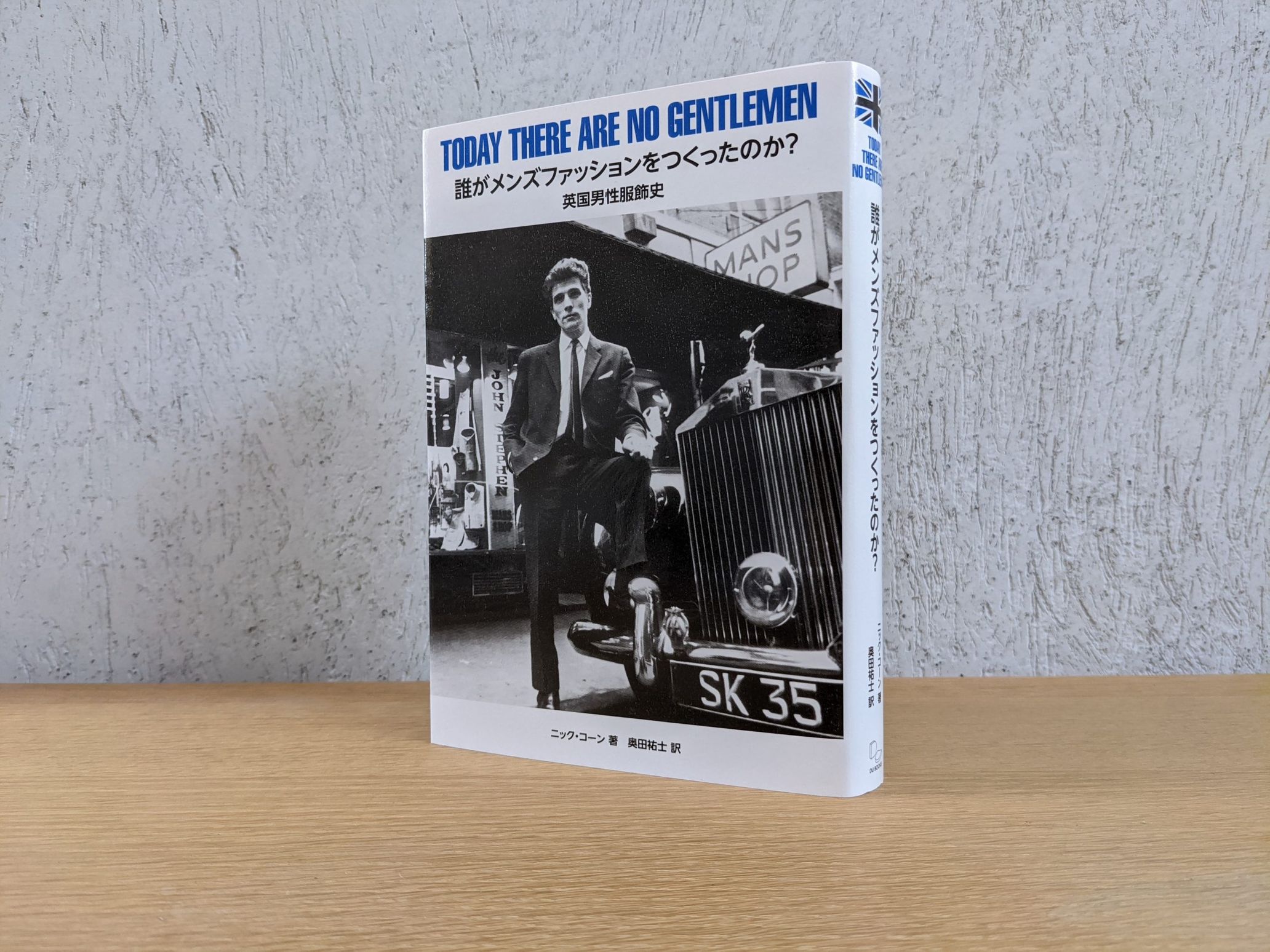

Born in London in 1946, and raised in Derry, Ireland. Sometimes known as a “father of rock criticism.” The film Saturday Night Fever was based on an article Cohn wrote for New York Magazine in 1976. In 2020, Today There are No Gentlemen (DU Books), which details changes in mens’ clothes through the boutique owners, designers, and rock stars who revolutionized English fashion, was translated and reprinted for the first time in Japan. Other works from Cohn translated into Japanese include The Heart of the World (Kawade Shobo Shinsha).

David Marx

Born in Oklahoma in 1978 and raised in Florida, he graduated from Harvard University with a B.A. in Oriental Studies in 2001, and from Keio University with an M.A. in 2006. He has contributed articles on Japanese music, fashion, and art to The New Yorker and GQ among other publications. He is a founder and editor-in-chief of the web journal Neojaponisme. His book Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, published in 2017, became a hit with six printings in Japan, an unprecedented number for a book focused on the history of clothes.

Twitter: @wdavidmarx