Right now, the observable audience for city pop among English-language communities is young and growing. You can find representative circles on sites including YouTube, Reddit, Tumblr, Instagram, and now TikTok, on which Miki Matsubara has been trending since last December. What’s most interesting about the young non-Japanese city pop fan groups is the encounter between a pure passion and a void of context for the larger Japanese music landscape of the 80s.

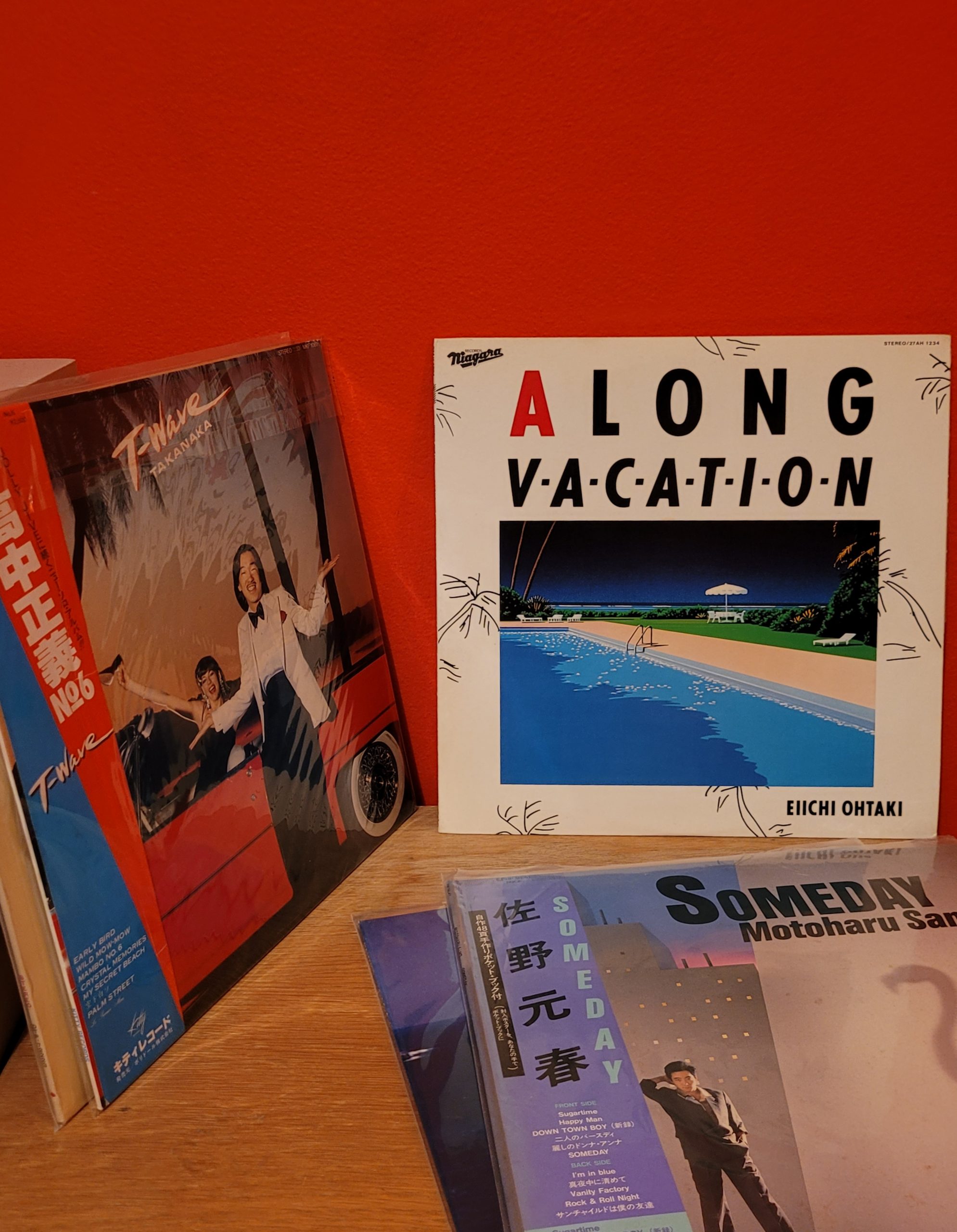

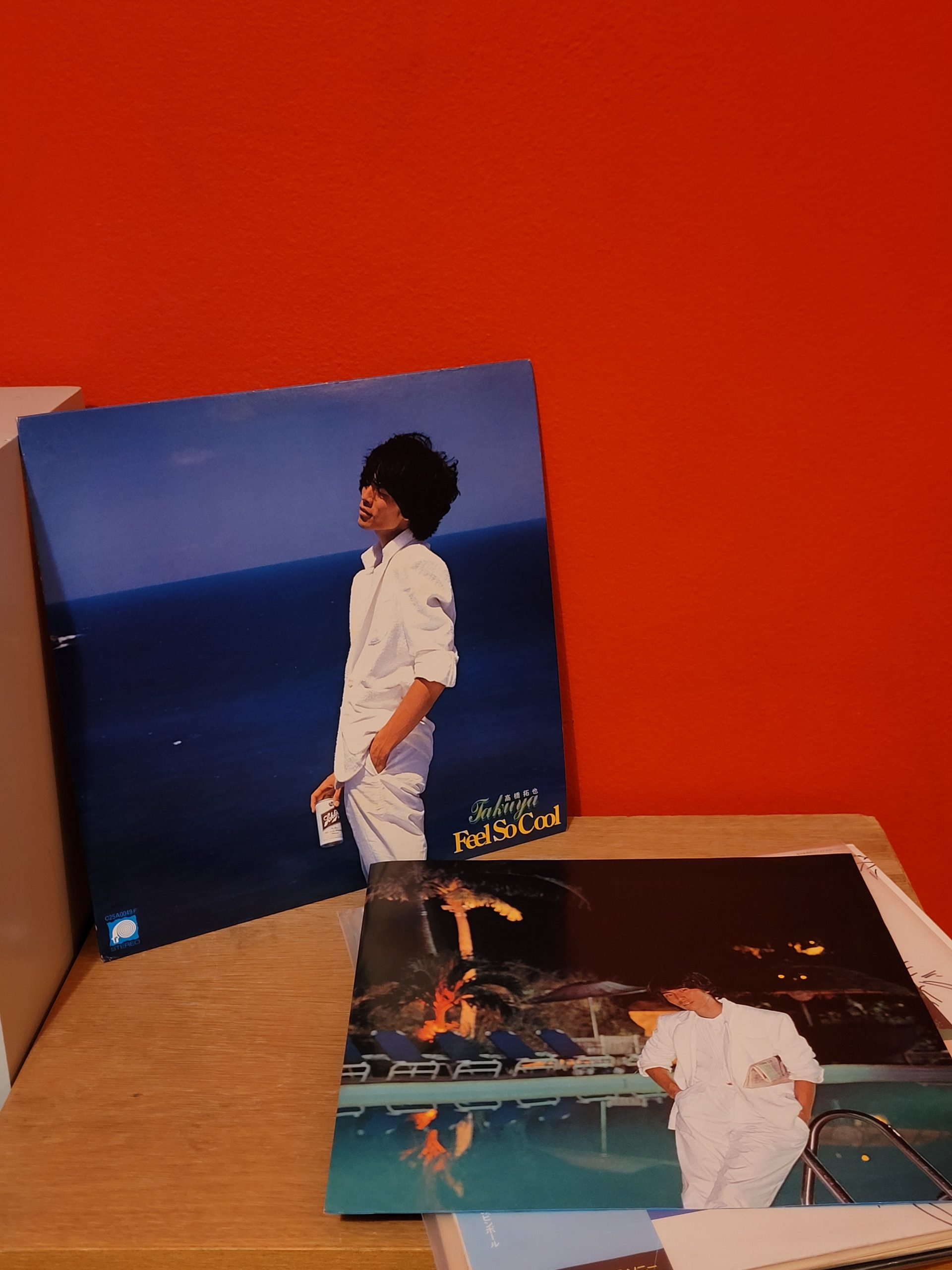

Within that void, there’s still a range of fluency— I suspect it’s the newest initiates in these communities who contribute 80s-flavored fanart, while those who’ve spent some more time with the music move on to making YouTube mixes and memes. The communities are largely in agreement over the musical core of the genre— principally songs by the likes of Tatsuro Yamashita, Mariya Takeuchi, Miki Matsubara, and Anri— but categorizations of the sound and aesthetic of city pop vary. The most orthodox presentation would be through the paintings of Hiroshi Nagai— if not by images of his own creation (featured both on genre classics like A Long Vacation and new releases by Light in the Attic and Ikkubaru), then through a shared imagination of the American west coast. But other ideas fill the contextual void for young fans— the music reminds them of exotic lights in Tokyo, 90s anime like Sailor Moon and Golden Boy, even video game pixel art. For some, this may appear to be where the seams of city pop tear— the genre’s presentation across these websites, if scrutinized, doesn’t show a pure origin or common movement.

I suggest that this is actually where city pop provides a future for its fans. It’s a constructed genre, and one relatively new in its current terming— Cunimondo Taniguchi of Ryusenkei recently discussed the history of its name with Tokion. As a constructed genre, it’s in the company of yacht rock, a parallel phenomenon from recent years connecting AOR and blue-eyed soul music from the west coast. An authoritative resource on yacht rock is Yacht or Nyacht, a website which scores and ranks songs by absurdly specific parameters to provide a clearer picture of the genre. For its new international audience, city pop doesn’t have such organized criteria (yet).

Light In The Attic, the American record label that received a Grammy nomination for their compilation Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980-1990, has contributed greatly to the pool of Japanese songs available to listeners outside of Japan.In the liner notes for Pacific Breeze: Japanese City Pop, AOR & Boogie 1976-1986, DJ and producer Mark “Frosty” McNeill calls city pop “more of a vibe classification than a movement,” and also writes: “as we know, vibe runs deeper than genre.” I spoke with Frosty over the phone, asking about his definition of vibe, and how the new accessibility of city pop (no doubt influenced by the work of Light in the Attic) might set the course for its future.

“The fun thing about music, I think, is in the blurry edges— the overlapping nature of music,” he said. McNeill co-founded the Los Angeles-based internet-radio station Dublab in 1999, and tends to think about music in the real-time logic of radio playlists. “For me, crafting a radio show is purely offering a flow of music that’s all about vibe, about sonic journeys,” he explained.“I think that in a single DJ set, radio show, mixtape, compilation, album, etc., you want it to feel like a journey. You don’t want it to feel monotone. So in the pacific breeze compilations, you want to have songs that are veering more into the folk territory, some more into the instrumental, tropical, library territories, some more into disco, funk….genres get carried away, whereas sound says a lot. So I think vibe and sound are really important.”

The experience of finding a new sound, regardless of one’s understanding of any present lyrics, engages a listener’s imagination. It has often been noted that Japanese music in the 70s evolved with a new admiration for American popular music. What can be seen now, though, is a new side of this phenomenon— Mac DeMarco, for example, has repeated over the years how inspired he has been by the music of Haruomi Hosono. Beyond vibe, there’s definitely a question of cultural distance and influence to be explored, which Frosty made sure to emphasize when I asked about the new music around the world sampling or taking influence from city pop.

“Hopefully it encourages domestic Japanese artists, as well, to just do their thing…to continue that trend of innovation,” he said. “It took Hosono and crew, Happy End and all of them, to make it okay to sing in Japanese over pop or rock. It was really shunned for a while. It was like, you can’t be cool if you’re not singing in English. And I think there is that stigma in rock and roll, and in other forms of music around the world…people think that because there’s a dominant western pop machine, their own unique expression…for years it was thought that it wasn’t cool. I think that it’s changed a lot because we’re in this golden age of archival reissues and access to international music…people are seeing a real beauty and value in the cultural expression through familiar sonic footprints and foundations. I think that’s really wonderful.”

My own wish for city pop is for it to stay loosely defined as it becomes more available and popular internationally. It’s great if people are inspired by the songs of Miki Matsubara or the paintings of Hiroshi Nagai; it will be disappointing if the genre is perceived as a canonized aesthetic. I want people to continue to find joy and inspiration in their journey through this music; if the next big group of young people really is finding city pop through TikTok, so much the better.