I wonder: when was the last time I saw him as a rapper? That memory is fuzzy now, but there’s something I remember vividly. In a small, underground space with bare concrete and no stage, he was exhaling words on his own. He didn’t even have a mic. I remember something about it made me think twice about calling it a performance or spoken word.

Fast forward to 2021. I listened to Shinganginga, which arrived at my doorstep, and turned the pages of his hand-made book while checking its texture. I asked to interview him because I genuinely wanted to know how he got to where he is today with his expression. Our conversation began as if we were carefully picking up the fallen pieces.

What living in nature taught Sibitt

—When did you start living in Kyoto?

Sibitt: Around seven years ago.

—Has your lifestyle changed?

Sibitt: It was like my life did a 180. I’ve loved nature since I was small, but it was like I went even deeper. Also, many people in Kyoto have an artisanal disposition. I get into trouble whenever I take orders from them and whatnot (laughs).

—So, you live in the mountains, not in the city.

Sibitt: Yes. I’ve always enjoyed being in touch with nature. But when I arrived in Kyoto, I learned I would get eaten alive if I had superficial motives and that my life could slip away.

—You mentioned artisans; do you work with them?

Sibitt: Yes. The first person I met with an artisanal spirit was someone who worked in the mountains. He works in forestry, and he buys Japanese horse chestnuts from grandpas and grandmas and makes many utensils and bowls out of them by himself without selling them to anyone. He’s about ten years older than me and scolded me all the time. It’s as if he’s cut off from society, but meeting him made me realize I wanted to continue creating too. It was fate. People often ask me if I’m a lumberjack or someone who works in forestry. But I also don’t know what my occupation title is. My experiences and work directly tie into writing poetry. That’s all. When I saw him creating things in silence, without thinking about his status or other people, it made me want to take my work more seriously.

—You write poetry and also produce music. You made Shinganginga by yourself.

Sibitt: I couldn’t even picture myself creating music. I didn’t intend on doing hip hop at first. It just so happened that I had friends around me who explored verbal expression. My friends who used to make music became adults and stopped making new music. When it came time to write poems to the music, fewer and fewer people understood the spirit of the individual’s sound. I pondered what sound I wanted to write poetry to; it was silence. Without sound, there were no limits. It was only recently that I started producing because I wanted to make music just a bit.

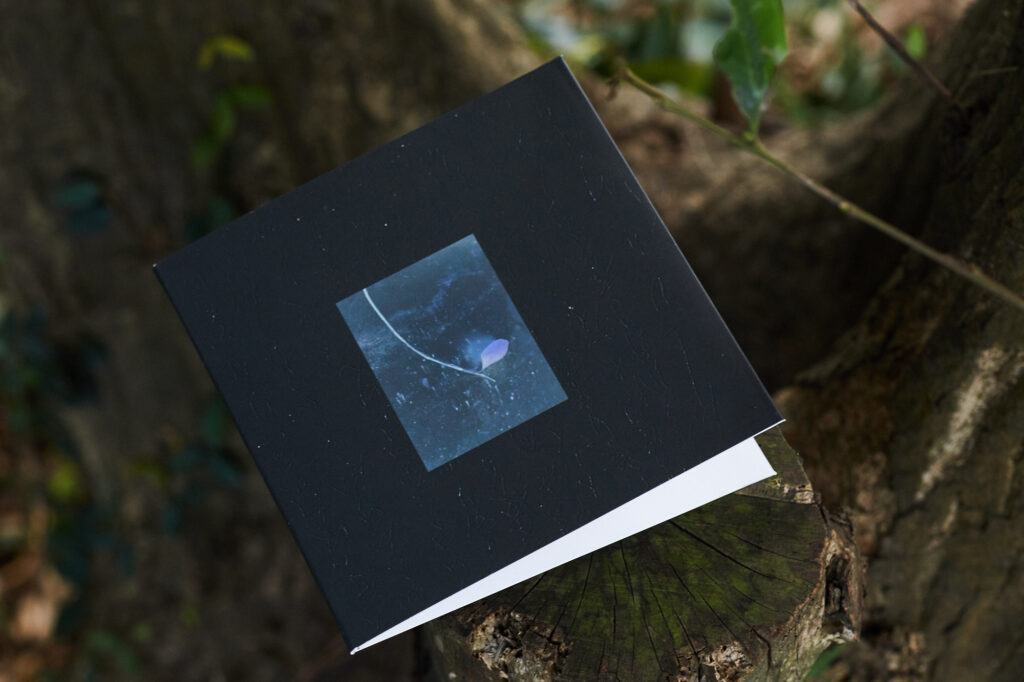

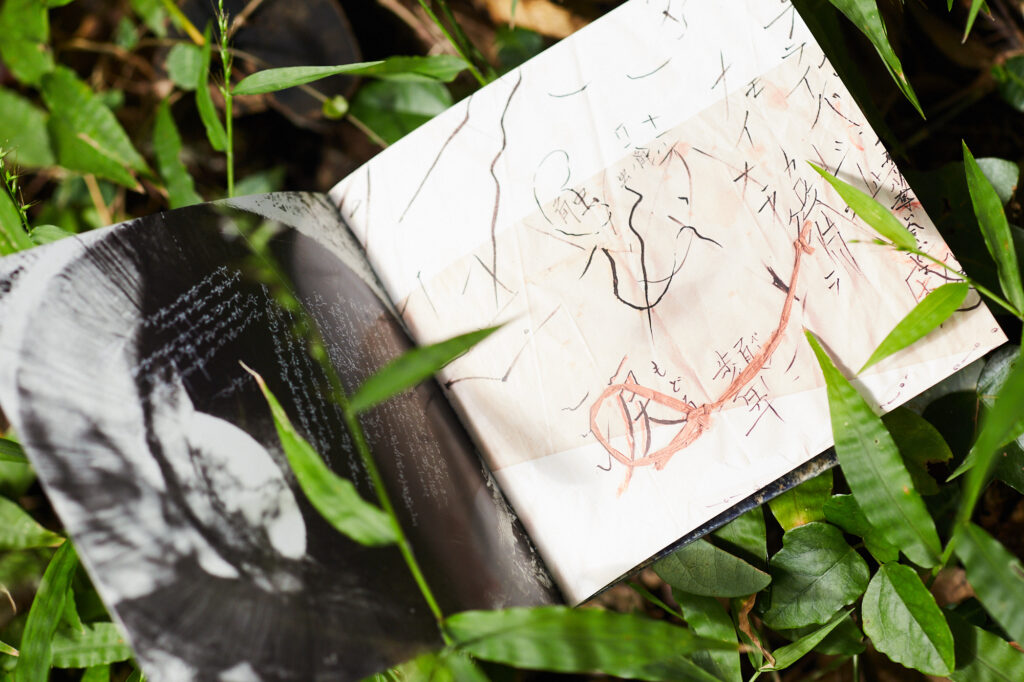

Shinganginga is Sibitt’s self-produced album released in May. He made the tracks by himself using Yamaha equipment from the 80s and 90s. The 13 songs embody his insatiable curiosity to express himself in Japanese—a phantasmagoric sound featuring rapping, spoken word, and singing.

https://sibitt.exblog.jp/28546796/

<心眼銀河-SHINGANGINGA-> 蝶道 – CHYOUDOU- 作詩・作曲:志人/sibitt

<心眼銀河-SHINGANGINGA-> 玄+時無種殻 -GEN+TIMECAPSULE- 作詩・作曲 志人/sibitt

<心眼銀河-SHINGANGINGA-> 夢遊趨 – Gun Lap Run- 作詩・作曲 志人/sibitt

— Shinganginga is the first album of this new phase.

Sibitt: Another reason I made it is because I was asked to try my hand at producing music. Someone asked me to make songs for zero to two-year-old babies last year. I didn’t know what to do because I had virtually never made music, so I tried playing old Yamaha—which I call 山葉 (the Japanese characters for mountain and leaf, read as Yamaha)—synthesizers that you could buy at a thrift shop. I can’t read sheet music, and I had never studied it. I stepped back and wondered, “What does music mean to me?” I felt like everything from the cries of cicadas to everyday sounds was music. I tried thinking like a baby and played with sounds to discover something that would strike a chord.

Shinganginga comes with a “Kashi (visible) card,” a 16-page collage of handwritten notes. On the self-released version, Sibitt wrapped each copy by hand with his “Shingan (mind’s eye) words,” which he made with his eyes closed using a special calligraphy sheet dyed with astringent persimmon juice.

Looking back on Sibitt’s musical trajectory; discovering hip hop

—I met you when Origami’s (editor’s note: Origami is a hip hop crew that took the Tokyo hip hop scene by storm, composed of MCs Sibitt and Nanorunamonai and producer onimas) first eponymous album came out in 2003. Could you talk about what kind of music you listened to before Origami and what you wanted to do?

Sibitt: When I was roaming around Asia in my youth before I started making art, I didn’t listen to hip hop at all. I listened to Boredoms and Rashinban. In terms of DJs, DJ Spooky. I also listened to goa trance music like Hallucinogen. While traveling, I listened to stuff that made me go, “What in the world is this?” I liked music that went one step further. I remember how this street vendor in Asia was playing a cassette tape; it was DJ Krush’s song. When I asked the street vendor, “Where is this music from?” they replied, “It’s Japanese music; it’s music from your country.” I “met” Dj Krush not in Japan but on the streets.

—And then you started doing hip hop once you returned to Japan.

Sibitt: In part, because I was a student, I had the strong urge to express and create something. That’s how I met friends who were making hip hop music. I went to Waseda University, and there were these rooms for extracurricular activities on the basement floor, which was chaotic. A group of misfits called Reggae Stars got together in one of the rooms there. The next room was where the Brazilian music society and sign language society got together. The first time I held a mic was at a block party with turntables at a park. Meaning, the first time I held a mic was through reggae.

—When Origami entered the scene, American underground hip hop was having a moment. There were similar groups out there, but Origami was different. I felt like you two rappers and the producer deviated from the category of hip hop.

Sibitt: Of course, a part of me is obsessed with and interested in hip hop’s great culture, but I’m not in a position to be like, “This is what hip hop is.” When I was younger, I would freestyle and [join] ciphers. But the music that excited me wasn’t old-school hip hop. I would visit my friend who was knowledgeable in different genres, and after we listened to underground hip hop, we would watch Fishmans’ music videos. I did random things when I was young.

—I’m sure the musical influence from Origami was significant.

Sibitt: Concerning Origami, onimas, who’s Taiwanese-American, started listening to post-rock music like Tortoise and Mice Parade, and the tracks began having non-hip hop elements. I just liked music that you couldn’t categorize—music that surprised you—more than traditional hip hop. It might be because I had begun thinking about what kind of music I wanted to make. I played live shows in the hip hop scene for a long time, but then I started doing live shows with people in totally different genres, like rock and hardcore, and as a result… I stopped chasing after people. Before I knew it, I would only perform live at hippy, commune-like places. It makes you wonder how it got to that point. I mean, I did sort of disappear too.

Sibitt’s relationship with language

—I presume your rap and language skills became polished as you evolved. What do you think?

Sibitt: That’s a difficult question. I think I can look deeper, thanks to both meeting people and, more recently, not meeting people. I’m considering expanding on what I learned when other people and I influenced each other and had some friendly rivalry. And the time where I immersed myself in words without outside influence.

—Your solo music and Origami’s music have elements of old Japanese songs. The music itself might have some western qualities, but were you always interested in Japan?

Sibitt: Yes. I was born in Shinjuku ward, but my grandparents are from Shikoku, and they couldn’t do what they wanted during the war. After the war, they cleared the land and built their own house in Nagano prefecture. They led a life where they gave up convenience, a la having a goemonburo (cauldron bath) and a wood-burning stove. I would visit them when I was small, in elementary school. I would go for walks with my grandmother, and she would tell me the names of bugs, birds, and flowers like, “This is called a waremoko (great burnet). It’s called that because ‘I too want to become like this’ (我もこうなりたい, read as waremokonaritai)” and “This bug is an antlion.” When I write poems, most of the time I’m like, “How do I know this word?” I don’t look it up and say, write a story about a particular flower. They’re more like words from the corners of my mind. My brain is imprinted with memories of my grandparents before I started making art and flowers and plants named by Japanese people through the power of language.

The teachings of theater

—So, it’s not like you go out of your way to focus on Japanese.

Sibitt: I don’t impose an “It has to be in Japanese” rule on myself. However, there’s a part of me that thinks about things while I go on walks like, “Where does my idiolect come from?” and even “What kind of country is Japan?” and “What is the emperor about?” I want to study the etymology of Japanese words and how they sound. I started doing theater recently. A few years ago, I acted in a play called Portal (screenplay by Shinichiro Hayashi), directed by Yukichi Matsumoto-san of Ishinha (editor’s note: Ishinha is a theater troupe founded by the late Yukichi Matsumoto in 1970. The group disbanded in 2017 after their show in Taiwan). That was the exact opposite [of what I do], as the theme was on using foreign words to create imaginary cities and games. And first, I wondered if I could even do it. However, I was interested because I felt like there were non-Japanese words trying to connect with Japanese words. Also, it was a play with a lot of words, and I realized I must’ve been digging myself a hole. I realized everything didn’t have to be in Japanese and discovered various foreign words as I absorbed them.

—What did you do in that play?

Sibitt: I played the role of Cloud, who is a nebulous person. I took on the role after studying it in the script. And under the condition that I could also come up with my lines. Until then, I never really read out other people’s words because I thought it might be untruthful. That’s where I drew the line. But I wanted to see what words could be born if there was some space to insert myself into that role. I was like, “I want to try it if I could do this at liberty,” so in a way, it was experimental.

—The play involved physical expression too. Did you discover anything new aside from using words?

Sibitt: The movements of Ishinha were unique. As someone who fundamentally doesn’t see themselves as a hip hop person, I have a self-less side that creates things with no subject like “I.” It makes you wonder who’s speaking. When I moved my body in that state, it was as if I was there, but simultaneously not. It was a strange sensation like I was dead or a ghost. The moves were choreographed, so depending on the scene, you couldn’t move freely. When you have to lose both yourself and the role when you move, it’s like you become no one. That’s what I experienced from moving with Ishinha.

—Did you feel selfless since your rapping days?

Sibitt: I mean, there are so many cool rappers, but I can’t be cool.

—Don’t worry, your rapping is cool (laughs).

Sibitt: No, no (laughs). I don’t really like narcissism. I wonder if we could speak for plants or trees, things that humanity has strayed away from. Even if we can’t talk on their behalf, perhaps we could translate what they’re saying, even if it’s wrong. When you speak as a person addressing other people, it becomes routine. Honestly, I believe [the plants and trees] speak to us in sounds that go beyond language. I work with the thought, “I wonder if now is the time for me to listen and translate,” in my head.

(Continued)

Sibitt

Sibitt was born in Japan in 1982. He is a poet, author, songwriter, and storyteller. Through examining his means of Japanese expression, he has become an artisan of words who shows new possibilities hidden in language. Aside from music, Sibitt works as an artist in domestic and international performing arts and classical theater. Starting in 2020, he began hosting 8∞, a project of endless stories with international artists. Currently, seven poets/ “voice performers” are involved: Sibitt, Khyro, Rully Shabara, Nanorunamonai, Bleubird , Bianca Casady, and Gozo Yoshimasu. In 2021, Sibitt released his self-produced album, Shinganginga alongside Shikakushi・Shokkakushi Shinganginga Shokei.

sibitts official blog Wheres sibitt? : sibitt.exblog.jp/

TempleATS: templeats.net/

8 ∞:88project.info/

Translation Lena Grace Suda