When you hear the term street style, what image comes to mind? It might differ according to the era, but it’s safe to say many people think of brands that represent Ura-Harajuku. “Urahara” street culture has reached big-name fashion houses like Louis Vuitton and Dior, thanks to Virgil Abloh and Kim Jones.

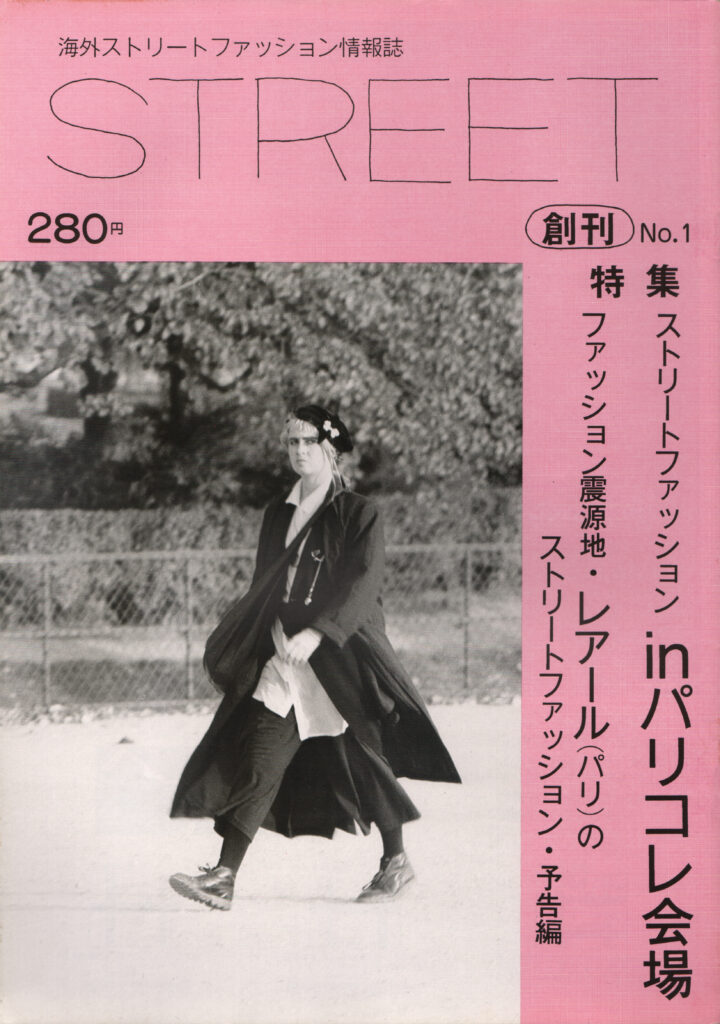

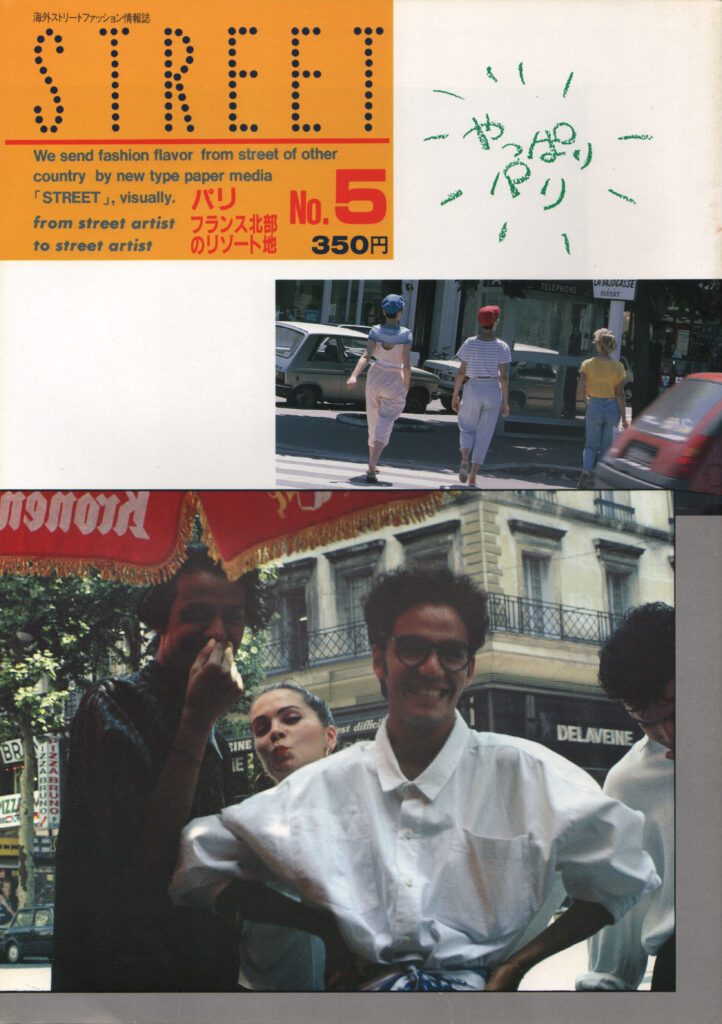

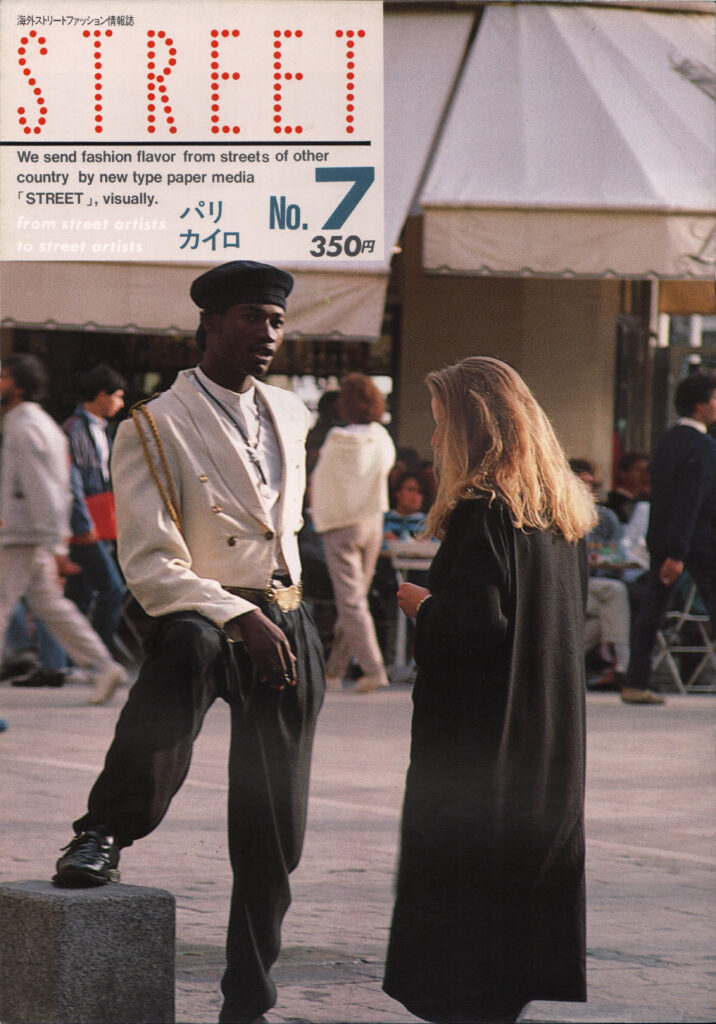

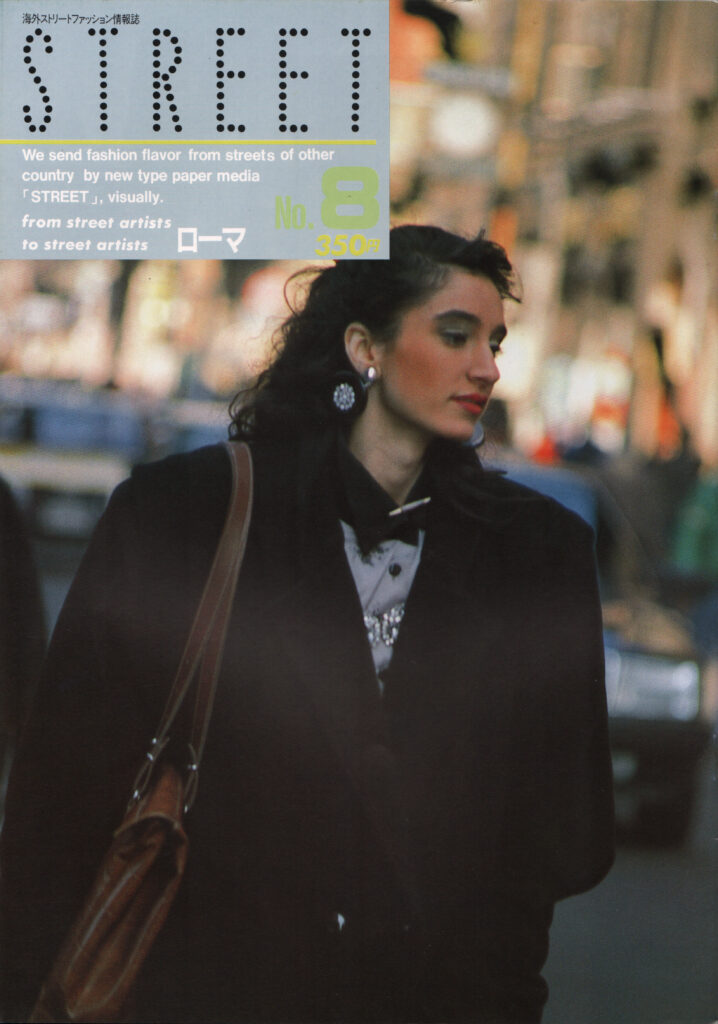

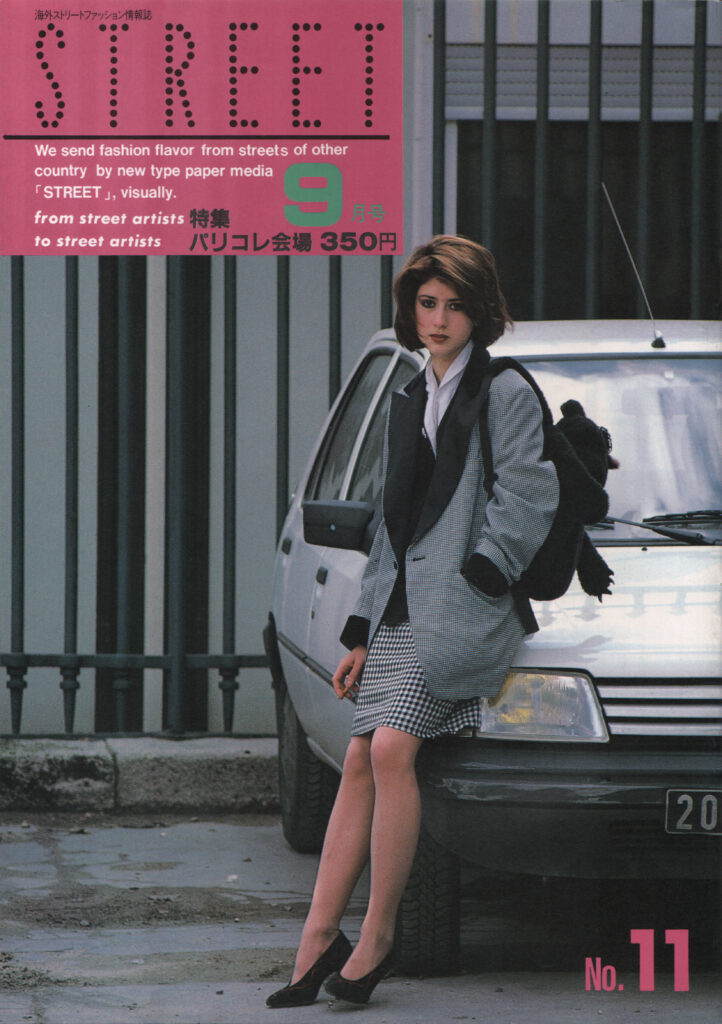

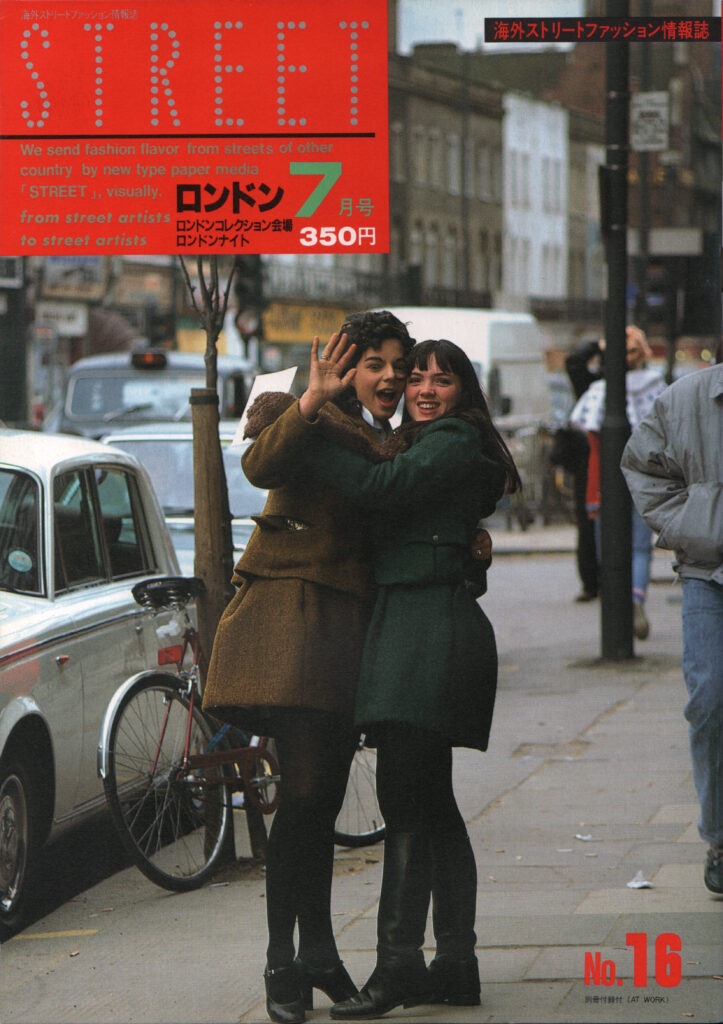

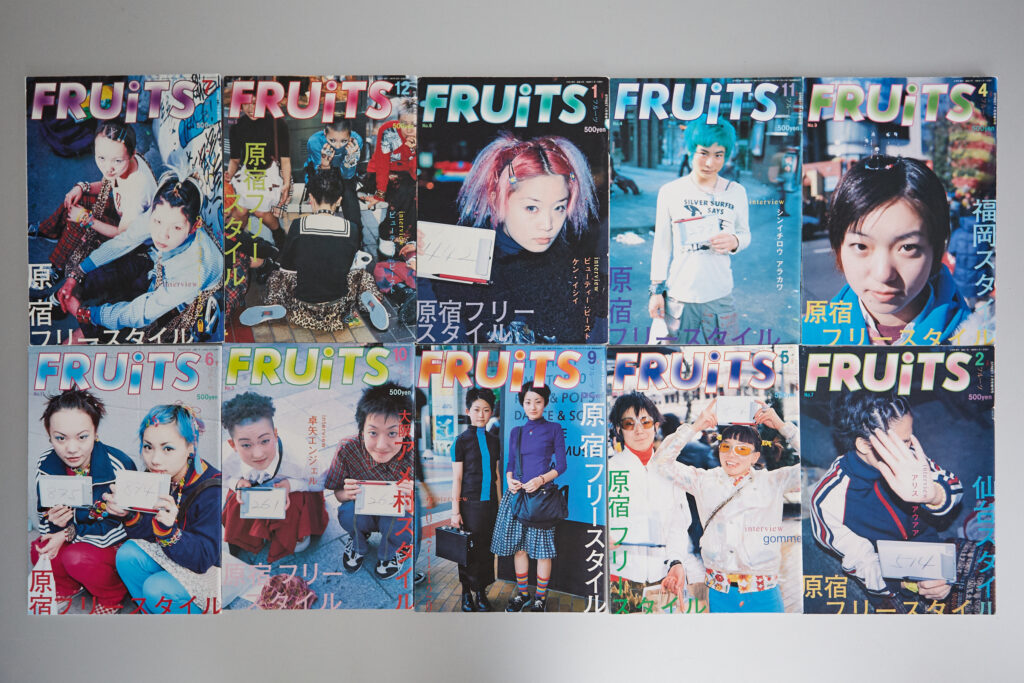

In contrast to the Urahara hype of the mid-90s to early 2000s, a distinctly Japanese take on styling became popular, such as both domestic and international brands combining techno elements and traditional Japanese aesthetics. Shoichi Aoki, the chief editor of FRUiTS, launched in 1997, latched onto the phenomenon early on. In 1985, Aoki began publishing STREET, a magazine featuring street style in places like London and Paris, and has continued to witness street style around the globe since then. He says that the street style of Tokyo in the mid-90s had an appeal precisely because it was from Japan.

Aoki spoke to us about the transformation of street style throughout the mid-90s to 2010s to today. In part one, he shares his views of the years between 1997 to 1999.

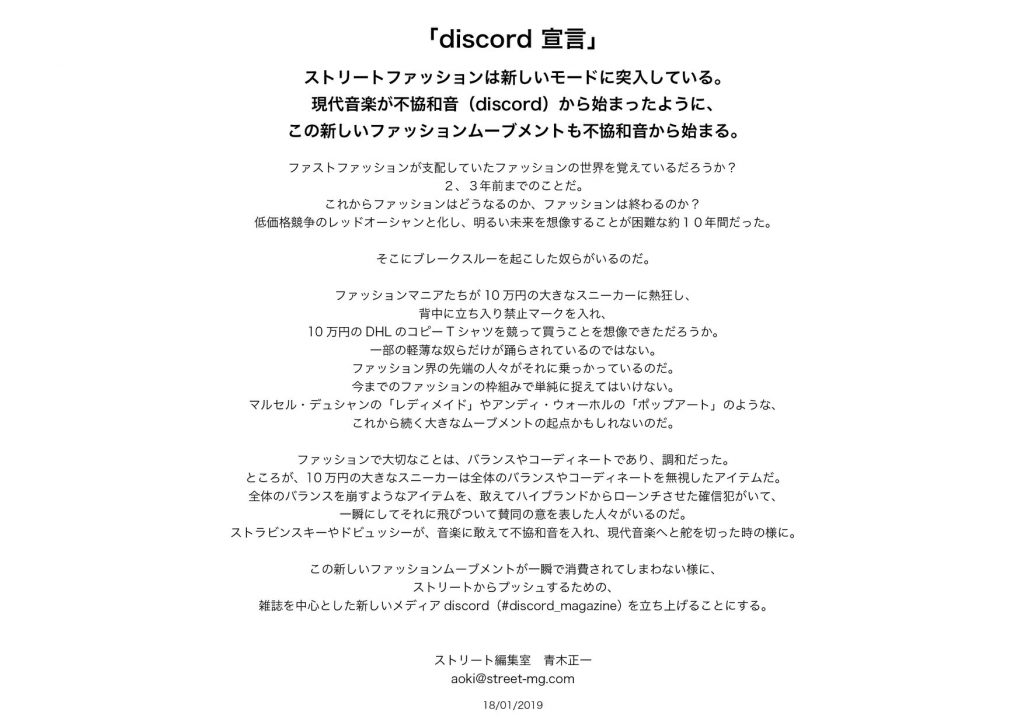

——In 2019, before covid, you posted “A Declaration of Discord” on your personal Facebook page. Simply put, your post aimed to summarize post-Vetements movements from a street-style perspective. You also talked about the function of Harajuku as a city. I followed your project with enthusiasm because of your novel point of view. Things have changed drastically since then.

Shoichi Aoki (Aoki): I know (laughs)! People might’ve forgotten this already; in the early 2010s, fashion was in a dark place because of the rise of fast fashion. It seemed to me that brands like Off-White were trying to bounce back from that. Until then, there was no direction. Because the price of clothes had generally gone down, smaller designers and shops, with hopes of growing, were backed into a corner. Even big commercial corporations were struggling. Just when people were wondering what would happen in the future, Demna Gvasalia of Vetements (the creative director of Balenciaga) and Virgil Abloh of Off-White (the artistic director of Louis Vuitton Men’s) suddenly came on the scene and changed the landscape vastly. Before they appeared out of the blue, I couldn’t imagine what was to come. Before covid, tourists from China and such would walk around Harajuku dressed in only Off-White. Usually, when people wear the same brand from head to toe, they look like they’re wearing a circus costume. But with Off-White and Vetements, even fashion beginners could look cool wearing the same brand from head to toe. I felt like it was a revolution in fashion. In the 1980s, some people wore only Comme des Garçons, but it didn’t look good when a beginner did it.

——Because you take photos of people who put outfits together using their unique taste, I assumed you didn’t like outfits like that. I’m surprised by your positive outlook.

Aoki: Yes, I [have a] perfectly positive [outlook on it].

——But do you genuinely find such outfits interesting? I’m personally only half-convinced. It seems crude to don too many logos.

Aoki: Really? The big silhouettes complemented the times. I thought the best part was how the fast fashion price tags didn’t sway them. When Martin Margiela first started, I was surprised to see that their price range was the same as Comme des Garçons. The clothes were grungy and made by a newcomer, yet the prices were the same as high fashion brands. I’m sure Demna referenced Martin’s philosophy in that regard. Demna started Vetements off with big silhouettes that looked like the extension of Maison Martin Margiela, right when he worked there as the designer (of womenswear). In other negative words, he copied the brand. But fashion enthusiasts that know a lot about the field praised and welcomed that. In the context of contemporary art, you could say it was simulationism, not copying. I think it would’ve been uncool if the prices were reasonable. Moreover, [Demna] moved fast, as seen in how the historic fashion house Balenciaga recognized him. I used to observe him with fascination.

The possibilities of post-fast fashion seen in tourists

——From 1985, when you founded STREET, to when you posted your declaration of discord, was how strong the fashion was the one criterion you had?

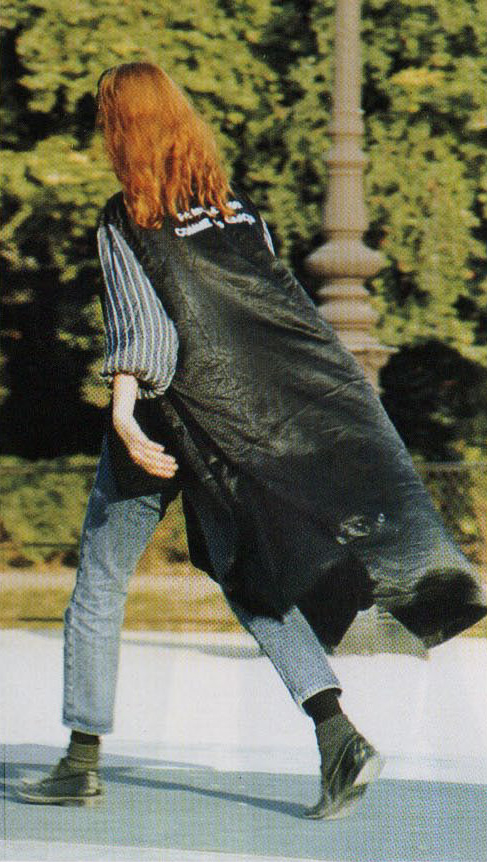

Aoki: Yes. Virgil and Demna’s clothes have good designs, product value, and concepts. I feel like people could wear their brands from head to toe and make it work. On the other hand, you can easily pair the clothes with secondhand ones, as they’re made with that purpose. Also, I think Comme des Garçons was the first brand to put its logo on clothes.

——You might be right.

Aoki: Other big-name high fashion brands of the time don’t come to mind. In the 1986 STREET feature taken at Paris fashion week venues, several people are pictured with the Comme des Garçons logo on the back of their coats. It was cool. I thought it was the staff uniform, but apparently, it was their staple product. I learned about it for the first time at their store the other day. That’s why I don’t look down on clothes with logos on them.

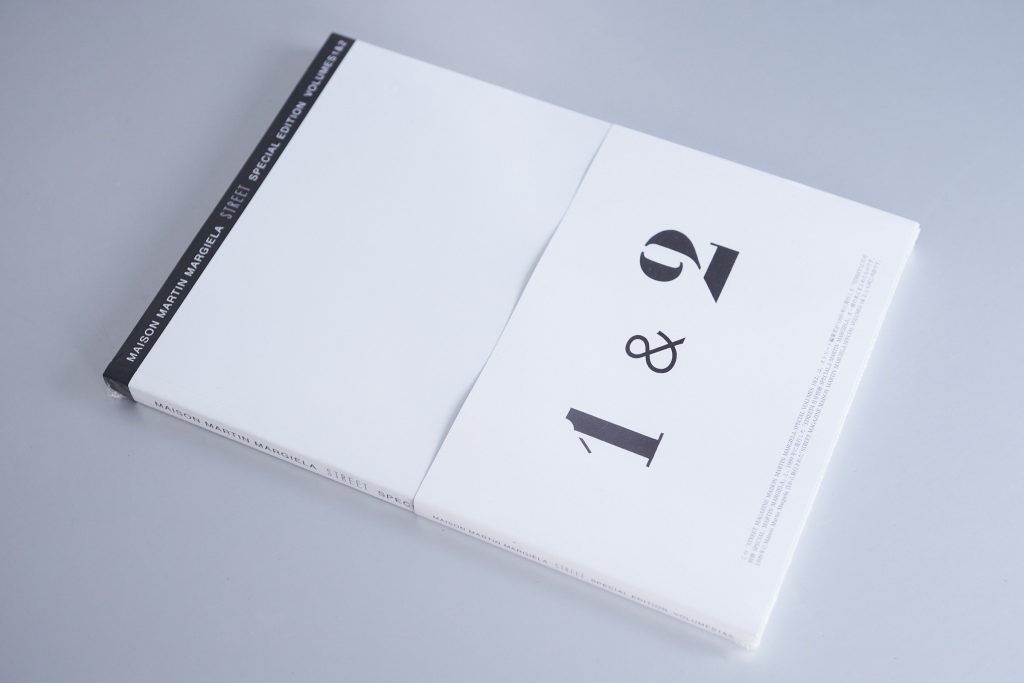

——But Martin Margiela, who you’ve made special STREET editions with, has the opposite stance; the brand has no logo.

Aoki: Yes. When I made the editions with Martin, he said, “I don’t mind what the logo is as long as it’s in a Helvetica-ish font,” and that surprised me (laughs). But the thread used to sew in the tag acts as the logo. It’s the predecessor of this quality that Demna and Virgil create, where it’s like a game.

—Come to think of it, FRUiTS started as one documentation of how the streets of Harajuku blossomed due to the influence of STREET. Similarly, with “A Declaration of Discord,” you tried to track how other Asian countries affected and changed shape in Japan.

Aoki: Yes. I felt like the tourists’ outfits excited people. After fast fashion became trendy in Harajuku, the number of “normal people” became too high, and it became hard for people to dress in their own way. Just then, more Chinese tourists visited Japan all of a sudden. They wore outfits that Japanese people would hesitate to wear. It made people realize like, “Oh! It’s okay to dress that extreme!” They realized that people wouldn’t talk about them behind their backs. You know how Japanese people are a bit reserved? That quality also played a role in the stagnation of fashion, but [the tourists] set the standard, and the city started looking different overall.

—So you had an inkling that exciting fashion was going to come back to life.

Aoki: I felt it strong. I was pumped, which is why I posted that declaration. If magazines, as a medium, had the momentum they used to have, then the declaration might’ve seemed premature, but I don’t [work at] that pace now. I wanted to mark something.

The rise of mixing different garments in the mid-90s

——I’d like to look back and firstly ask about 1997, which is when you returned to Japan and founded FRUiTS. Could you describe the era?

Aoki: During the 80s, Comme des Garçons and Yohji Yamamoto reigned supreme, but I still hadn’t taken street style photos in Tokyo for STREET. Back then, everyone in Japan was following the same trends; [a brand called] DC Brand was trendy, and that was it. The industry calculated that so they could make a lot of profit. I, too, wore Comme des Garçons and Yohji Yamamoto, but I didn’t want to take street style photos. Once the DC craze died down, it burned everything down with it—nothing was left. A friend of mine who’s a stylist told me it was hell then. After about a five-year gap, brands like Vivienne Westwood and Christopher Nemeth finally started becoming popular. I mean, fashion lovers existed before then, but thanks to DC waning, they stood out more. That was from 1994 to 1995. I started featuring Tokyo in STREET, and well, it’s not that interesting to look at now, but the fashion back then had a different spirit from that DC craze. People gradually began mixing brands in their outfits. Brands like 20471120 and beauty:beast came out, and Margiela opened their shops here.

——There was a change in the air.

Aoki: It changed abruptly around 1996. There were no trends. People mixed brands, reconstructed garments on their own, styled Japanese clothes, and so forth. Each individual had a different style. In Osaka, Takuya Angel was trending a lot. Brands that did well are Vivienne Westwood, Christopher Nemeth, Milkboy, and so on.

——The primary influence was from London, yes?

Aoki: Yes, yes. It all started from the influence of the streets of London. Secondhand clothes weren’t seen as fashionable in Japan, but the culture of young people buying and styling secondhand clothes in London’s Portobello and Camden markets arrived here. There was a definite moment when that type of fashion rose in popularity. But I don’t think anyone noticed this quick evolution of Harajuku’s unique fashion until FRUiTS came out. If I try hard enough, I can tell you the year and month of the turning point; that’s how apparent it was.

——Were there any fashion icons?

Aoki: I feel like these five-ish students from Nippon Beauty Academy, Vantan Design Institute, and Bunka Fashion College changed the landscape. The era went from kids wearing Vivienne Westwood from head to toe to mixing brand products as the key ingredient. There were a couple of kids who were geniuses at putting together outfits. Those kids hung around in Harajuku, so people would look at and observe authentic Harajuku fashion instead of magazines and the media. They would go home and incorporate what they saw. Fashion progressed through that cycle.

——And that catalyzed for you to start FRUiTS?

Aoki: Yes. I still remember this clearly; when I was taking street style photos in Tokyo for STREET, I was struck by this pair’s style, whom I shot next to La Foret. You might not be too surprised when you see it now, but it was an outrageous outfit during then, right after the DC craze. This is the same with Margiela; those clothes are normalized now, but it was shocking when they first came out. I knew that fashion was moving tangibly, so I decided to begin FRUiTS. The following Sunday, I timidly went to the car-free zone to shoot, and the first person I spotted and approached was Aki Kobayashi-chan, who’s on the cover of the pilot issue of FRUiTS. She had such a presence about her.

——You mean that the fashion you saw couldn’t fit into the borders of STREET.

Aoki: Yeah. A new kind of fashion was emerging, yet nobody understood how big of a deal it was. I wanted to keep shooting on the down-low until everyone realized [how big of a deal it was]. Until magazines that copied FRUiTS came out a year after I founded it, I had it all to myself (laughs).

“I’m only interested in how beautiful an outfit is”

——From that point onwards, a distinctly Japanese way of dressing was born thanks to the influence of domestic and international styles like those featured on STREET.

Aoki: The internet didn’t exist then, and there weren’t significant trends, so people had to figure it out by themselves.

——Hearing you talk, I get the impression that you view the scene with a critical eye by going back and forth between the inside and outside of fashion. Are you interested in looking at society through clothes, or are you interested in the clothes and styling themselves?

Aoki: I’m only interested in how beautiful an outfit is. I believe street style is an art form, so it’s like I’m collecting artworks. Foreign media often ask me if there were grounds for FRUiTS-inspired fashion to be born, and I always answer, “Not at all. That’s why it’s good.” I assume they expect me to say something about rebelling against society. I feel like not doing so is more artistic.

——Today, people associate FRUiTS with women’s fashion, but in 1997, you featured many men too. How did fashion trends differ between men and women?

Aoki: This guy that used to wear Vivienne Westwood started saying, “I dress [in a] Urahara style now,” from around 1999. He was always ahead of the curve, but I was like, “Oh, I see.” If anything, I’m the one who’s being taught things.

——You weren’t like, “Wow, that’s cool”?

Aoki: I didn’t understand it at all (laughs). With Urahara fashion, if you don’t know the brand’s backstory, the look itself doesn’t look appealing. The same goes with the Ivy League-inspired looks of the past, but boys love that kind of stuff. To an outsider, they all look the same, and photos don’t convey the appeal. But boys switched to Urahara fashion quickly. The situation changed to one in which others would point and laugh at you if you wore Vivienne Westwood all over. Hiroshi Fujiwara-san started out as someone who wore Vivienne Westwood from head to toe, though.

——Compared to that brand, he’s modest-looking (laughs).

Aoki: But his influence is so huge now. He’s even influenced Virgil. I can’t seem to understand how he can be that impressive. Fujiwara-san must be a genius.

——Did you go to stores like NOWHERE (a shop established by Nigo of A BATHING APE and Jun Takahashi of UNDERCOVER in 1993)?

Aoki: I got the courage to visit NOWHERE two or three times. You know that they’d look at me weird if I frequented there (laughs). They incorporated the idea that Urahara shop staff were unsociable and scary into their style. It’s like adding bitterness to a dish. It’s one of the things they came up with. It’s like they don’t want people outside of the loop to visit (laughs). Once Urahara became an actual phenomenon, FRUiTS became a magazine for girls. It’s not like that was my intention, though.

(To be continued)

Shoichi Aoki

Photographer and chief editor. CEO of Lens Co., Ltd. Born in 1955 in Tokyo. After having a career in programming, Shoichi Aoki published STREET in 1985. He published FRUiTS, a collection of authentic portraits of the streets of Harajuku, in 1997 and attracted a global audience. After that, he put out the men’s version of FRUiTS called TUNE and .RUBY. Twitter:@FruitsMag

Instagram:@fruitsmag

Instagram:@fruits_magazine_archives

Instagram:@streetmag

Photography Kazuo Yoshida