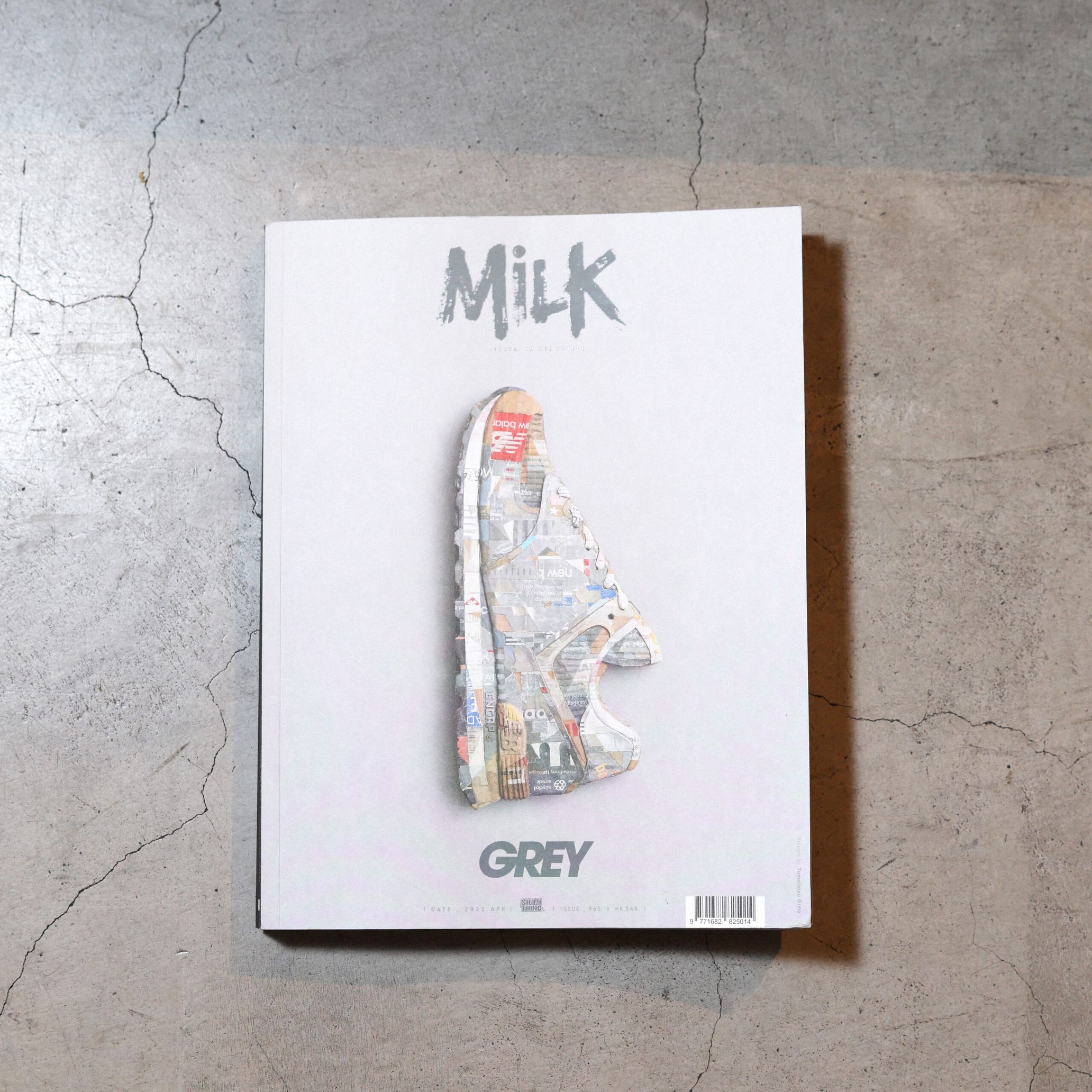

In January, artist Tomotatsu Gima’s art exhibition, POP COLLAGE LP+SNEAKER took place at hotel koe tokyo located in Shibuya, Tokyo. Stepping inside the solo exhibition, I witnessed an array of Gima’s works, including his sought-after sneaker artwork and collection made from analog records of popular artists from the 80s and the 90s, displayed as if in a sneaker and vintage record shop.

Gima reuses waste cardboard and transcends them into glorious art pieces with his original technique.

Relaying from Part One, where we talked about the analog records being the design sources of his new masterpieces, in Part Two, I asked him about his journey as an artist and his sneaker artworks. Furthermore, I learned about his prospect as an artist who grew up in Okinawa—a melting pot of various cultures—where he discovered the beauty of cardboard delivered from all over the world; and his rubodan projects, performing good deeds through art.

I found out about pop art, and it left a huge imprint on me

ーーFirst, I’d like to hear about your roots or your art history.

Tomotatsu Gima (Hereinafter Gima): I liked drawing since I was little, and when I was in middle school, my art teacher, who recognized that I was into drawing, recommended me, “Why don’t you submit your drawing to a content?” So I did, and I won a prize. I wasn’t so good at sports or studying back then, but when I received the award, I was like, “I may be talented at drawing!”…. So then, I decided to go to a high school that has an art course. I studied diligently after getting into high school, desperately wanting to hone my drawing skill. Also, that was when I found something that inspires me even to this day—It was a book I found on the bookshelf of the art classroom called POP ART. The book introduced works by artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein and taught me Pop Art, which inspired me a lot.

Later, I wanted to continue studying fine art in college, so I chose to go to Nagoya University of Art and took the Japanese painting course. Honestly, I wanted to study more about Pop Art, but the university didn’t have its course. So, I chose to study painting, but the context of Japanese painting was unexpectedly different from oil painting. Also, I’m the type that wants to finish painting as quickly as possible, but Japanese painting has a lot of steps to go through and takes a lot longer by nature. So, it wasn’t suitable for me at all; I didn’t hate it or anything, but my body and mind just weren’t there for it. Eventually, the teacher sort of gave up on me and let me do whatever I wanted. [Laughs]

ーーWhat an interesting experience.

Gima: Though, through making POP COLLAGE, I thought I was lucky that I had studied Japanese painting. In Japanese painting, we essentially use powder paint made from different colored stones, and I think this comes from someone’s idea in the old days who thought of making colors by crushing organically colored rocks. What I do is pretty much the same: I’m just collecting colored cardboard boxes and making them into small pieces to create art. In ancient times, people were using natural materials they found out there, like rocks, to make pigments, and just like that, I’m using cardboard as materials to create my works, which I happened to find outside of my house. Also, like how you can make orange by mixing red and yellow, you can do the same with cardboard. So this shows that the tips I use for my cardboard art mostly come from what I had learned from Japanese painting.

ーーIt’s incredible how you incorporate the ideas from Japanese painting into your cardboard art!

Gima: Finally, all those years of learning Japanese painting are paying off. [Laughs] Besides the process, I was also inspired by the stance and concept of Japanese painting. In Japanese painting, for example, when you’re painting a red apple, you have to paint it in the same shade of red to make it look exactly the same. I learned to appreciate the subject by drawing it to look real and using colors close to its actual colors. So, when working, I take a lot of time observing the subject. Also, with record artworks, I listen to the songs while working to get inspired.

ーーYou also make sneaker artworks, but why did you decide to make sneakers a motif?

Gima: When I was in college, I became interested in fashion items. As I didn’t know much about fashion, I read magazines and gleaned information through talking to people and learned little by little about it. Eventually, I discovered and got deep into the sneaker culture. [Laughs] Even today, I try to keep up with new sneakers and garner more information about old sneakers through people.

ーーWhen did you start thinking that sneakers are cool?

Gima: When I was in 6th grade, my dad decided to start jogging for the sake of his wellness and bought himself a pair of sneakers. It was white and red New Balance running shoes, and when I saw them, I remember being shocked to find out that there are such cool and light sneakers in this world. I begged my dad to get me one, too, and he told me, “Sure, only if you’re running, too.” Back then, I seriously sucked at sports, but since my dad got me the sneakers, I was like, “I gotta run!” and felt obligated to practice running. I couldn’t run at all initially, but I gradually became better at running after many practices. At the same time, I also started basketball, so this sneaker made me good at sports. [Laughs]

ーー[Laughs]. You re-create sneakers and others using cardboard—How did you start this creative cardboard project?

Gima: I had an atelier in Naha, Okinawa, next to a market. Every evening, there would be a pile of used cardboard boxes at the market. As I took a close look at them, I’d noticed that they were cardboards of canned food, juice, snacks, and commodities not only from Japan but also from the US, Europe, Asia, South America, Africa and all over the world. So then, I decided to replicate the products with these waste cardboard, which was the start of this cardboard art series.

Even before that, I’ve always wanted to upcycle waste materials but never took action. The waste cardboard boxes were ultimately shipped from various other countries to Okinawa, which is Japan’s tiny south edge prefecture. The cardboard boxes were in many different colors, and some had handwritten signatures and checkmarks. I felt hope from seeing these things. But after traveling thousands of miles to Okinawa, these boxes were turned into trash immediately after they were opened, and products were sold to the consumers. I felt compassionate towards the ephemerality of their lives and wanted to put a spotlight on them. So that was how I started the creative project under the theme of “Distribution and consumption.”

ーーYou also launched the project rubodan, which is also based around the theme of “Distribution and consumption.” Can you tell us about rubodan as well?

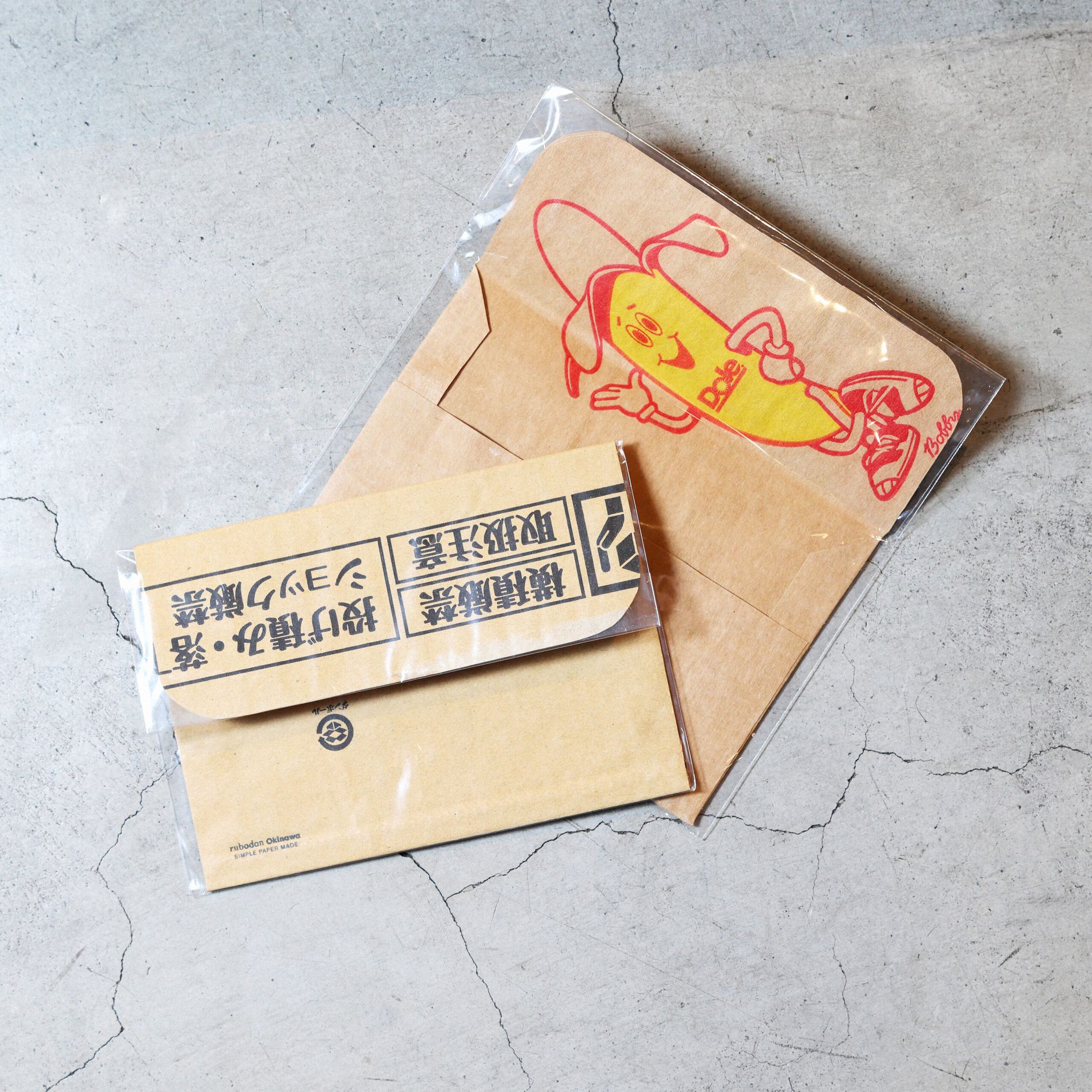

Gima: As I mentioned earlier, I wanted to start something using cardboard since I had an atelier next to a market. The first thing I made from used cardboard was a notebook. The idea was born when I saw the top layer of wet cardboard peeled off in the rain. I found out that you can easily peel the top layer off the cardboard by putting it in water—This was a major discovery for me—I found out that it’s easy to make papers from cardboard. After that, I made more notebooks and letter sets. This was the genesis of the cardboard stationery brand, rubodan.

ーーThis rubodan project is also carried out abroad—What kind of activities do you do in other countries?

Gima: Since cardboard exists everywhere in the world, through the rubodan project, I thought it would be cool if I could craft things together with people in other countries. Right when I was thinking about that idea, I was given a chance to go to Samoa in 2010 as a special dispatch worker from JICA Okinawa—a corporation that provides support and aid to developing countries. I studied about Samoa for the first time and learned that they rely mainly on supplies imported from abroad as it’s a small island. So they get loads of cardboard boxes, but their landfill facility isn’t good that there isn’t a place to burn them all. Despite so, the land keeps receiving so many packages. In the old days, Samoans were mainly eating bananas, taros, and foods harvested in their land, but imported food consumption has increased in recent years, and the land has become flooded with more plastics and non-biodegradable waste. When I found out about it, I started thinking of ways to help reduce the amount of trash in the country. So then, I came up with the idea of reusing cardboard and opened a rubodan workshop at an elementary school on site. I collected cardboard with the kids and put them in water to make paper. In schools in Samoa, they don’t have art classes, so kids don’t have much chance to draw in school. They didn’t even have pencils or paper. All they had was tons of cardboard, so I taught them that they could recycle cardboard into paper and draw on them. I drew pictures on recycled paper together with the kids and made a small museum in school. This remarkable event led me to make rubodan a brand in 2011, which I still run to this day.

ーーHow was the Samoan kids’ reaction?

Gima: They were really surprised to learn that they can make cardboard into paper. As they usually don’t get much chance to draw pictures, they were enjoying crafting things together. I think it was a great experience for the kids. Since I was rewarded with the kids’ smiles, I couldn’t just end this project in the short term. Although I call rubodan a project, I see it as equivalent to my artwork. So I keep this project going as a part of my art production.

The rubodan workshop in Thailand

ーーIt’s such a wonderful deed. Finally, please tell us about your future vision.

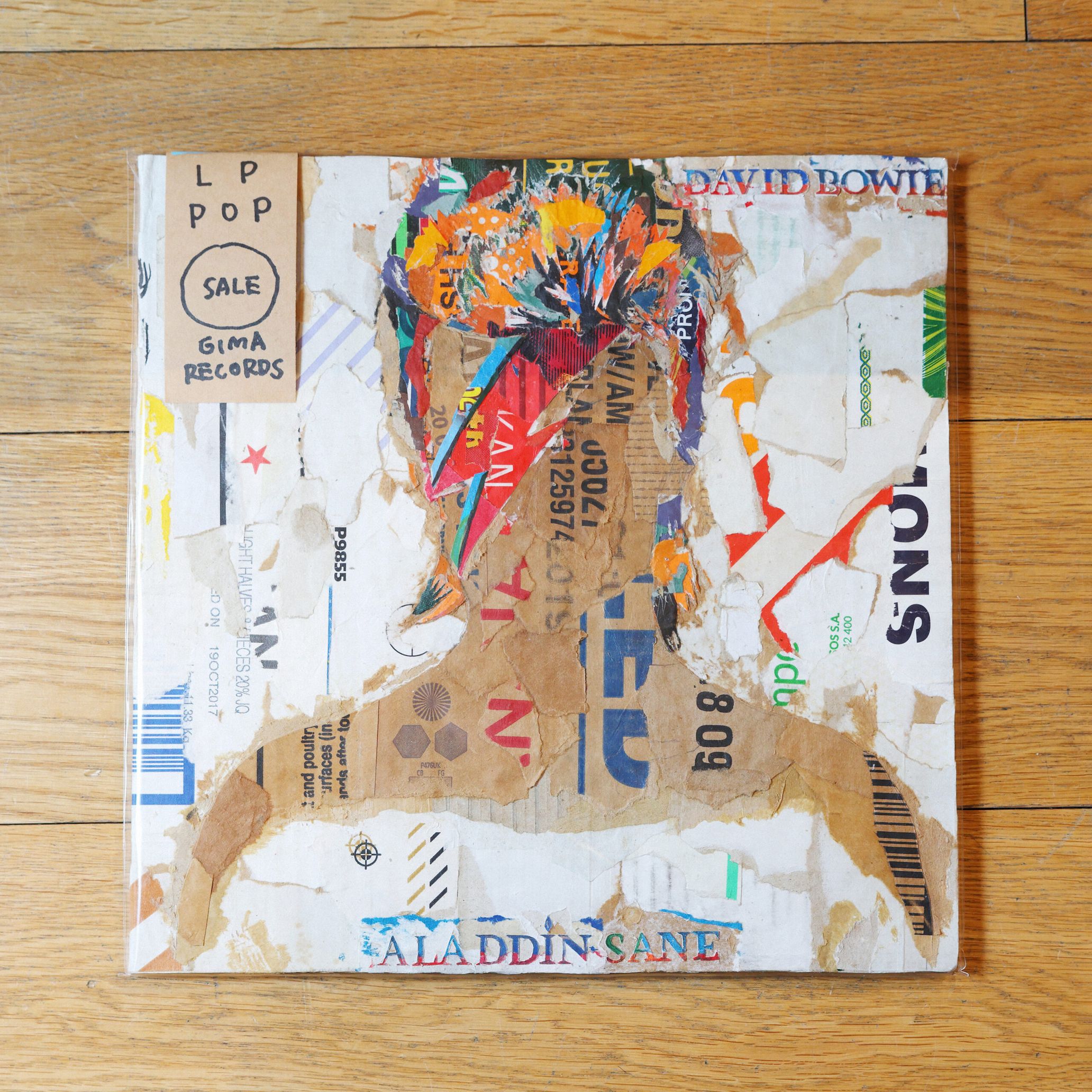

Gima: Through working with cardboard on a daily basis, I’m now starting to get more interested in humans. Take the David Bowie record artwork I have for this exhibition as an example—I purposely didn’t draw Bowie’s facial features. But people can probably still imagine his face. I’m interested in this kind of abstract expression, but also I’ve noticed that the colors of cardboard are similar to our skin tones. So, I want to convey more humans with cardboard in the future. As with record covers, you don’t quite forget the faces of people you’ve met in the past. So, when you look at my artwork, even without facial expressions, you may remember the faces portrayed in the original works or see it differently from the originals. It feels incredible to expand the range of the viewers’ perceptions of when they see my works. So, as my new attempt, I want to develop works focusing more on humans.

Tomotatsu Gima

Gima was born in 1976 in Okinawa. After graduating from Nagoya University of Art, where he majored in fine art, he flew to New York in 2004 and studied there for a year. He then came back to Okinawa and started his career as an artist. After joining many group exhibitions, in 2018, he accomplished his first solo exhibition, titled SOME POP, based around the theme, “Distribution and Consumption,” and earned a lot of praise. He later launched the brand rubodan, selling notebooks and letter sets made from reused cardboard. He also travels around Asia, communicating with locals and opening workshops, and collaborates with Orion beer, producing stationery sets made from reused cardboard with the goal of zero waste.

Instagram @tomotatsu_gima / @rubodan

http://www.rubodan.com

Photography Shinpo Kimura

Translation Ai Kaneda