Photographer Ari Hatsuzawa has traveled far and wide, from North Korea, Okinawa, and Iraq to the areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, and has continued to capture different subjects with a journalistic eye. His photos get burned into the minds of those who see them within seconds, and the message they convey makes us feel something powerful.

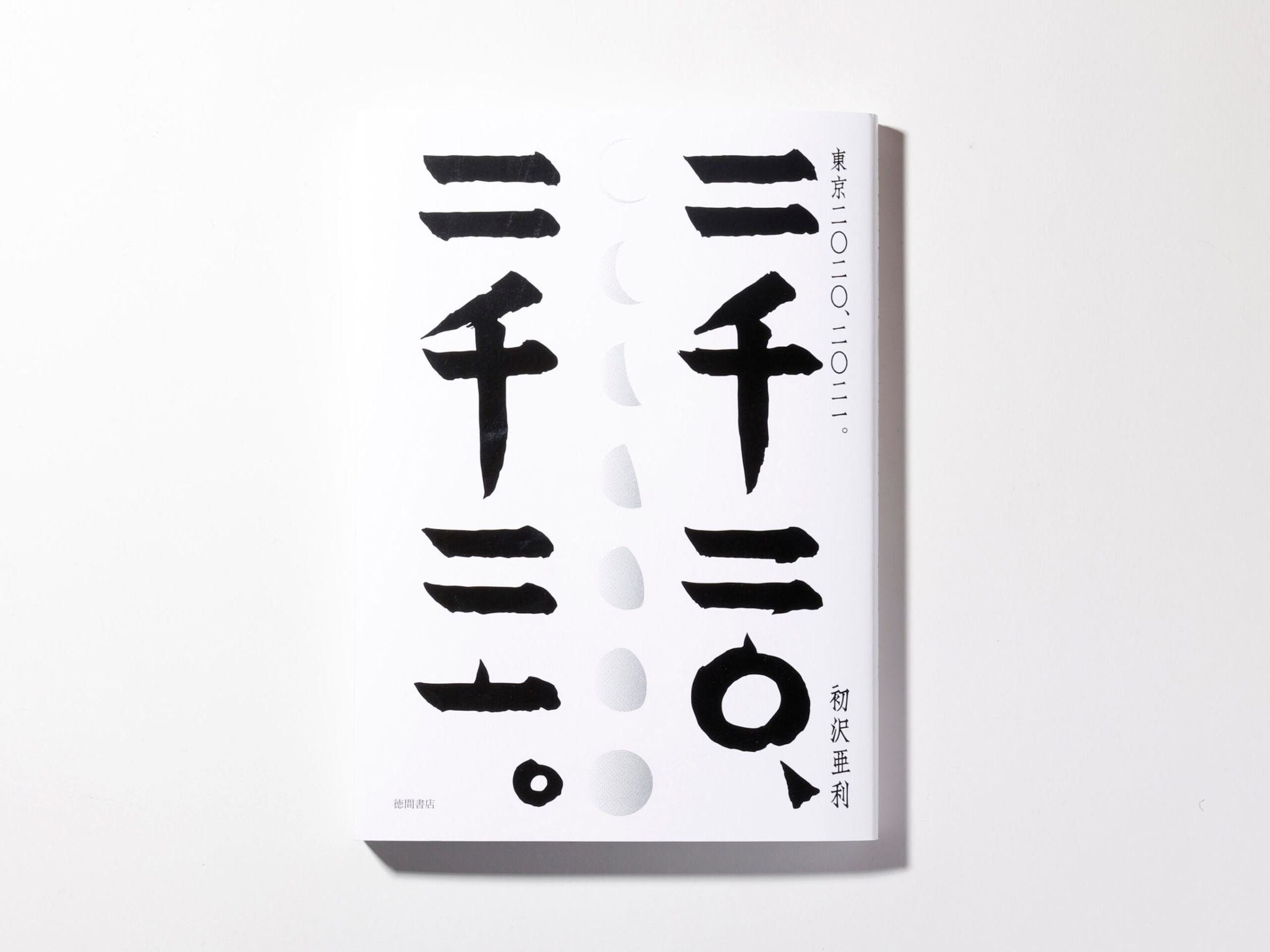

Hatsuzawa photographed Tokyo under covid for about two years, from 2020 to 2021. During the stay-at-home period, he roamed the streets of Tokyo with his camera and took photos of the outside world. A collection of these photos, Tokyo 2020, 2021, was published at the end of last year. The photos were shown at his exhibition, “Tokumeikasuru Tokyo,” held at Rooney 247 Fine Arts in Nihonbashi-Kodenmacho. The book received the 30th Tadahiko Hayashi Award, which is one of the three prestigious photography awards in Japan. Hatsuzawa’s photos, which depict the beauty that lies in everything, have caught the interest of the photography industry and journalism industry.

His photos of the hidden side of Tokyo under covid are captivating. What did he see in Tokyo during the pandemic? The photographer talked to us about the catalyst for picking up photography and what he discovered about Tokyo by taking these photos.

——How did you spend your time during the pandemic in 2020 and 2021?

Ari Hatsuzawa (Hereinafter Hatsuzawa): I haven’t stayed at home for a single day for the past two years. I think covid started in Wuhan around the end of December 2019 and came to Japan at the beginning of the following year. Then the Diamond Princess outbreak happened, and once it could no longer be under control, people started getting off the ship on February 29th. I felt like it would turn out to be an important event, so I went to the scene without thinking about creating a photo book. From that point on, I just observed [the pandemic] by looking at numbers like the increase of covid cases, severe cases, and the number of deaths. There were still a few dozen cases back then, so I thought the possibility of getting infected was very low. When lockdown started due to the state of emergency in April 2021, I wondered why everyone was so scared.

——It sounds like you judged the situation rationally.

Hatsuzawa: When I was in places like Iraq or North Korea, I pondered the probability of my dying. If there’s an ongoing war, my chances of dying would be much higher in Iraq than in Tokyo under covid. Is the probability 1 in 10,000 or 1 in 100? I have a habit of determining when I should feel safe, like when the chances are 1 in 10,000. Even when I went to North Korea, I returned in one piece, as I didn’t do anything out of order. When I came back to Japan, people told me things like, “I’m impressed you came back safely,” but that comes down to the image in people’s heads. It’s difficult for people to be rational and think about what makes something scary. They don’t even try. The same goes for covid. Although I stayed in during the state of emergency, I honestly felt resistant towards people who were agitated by the situation solely due to the image they had in mind.

——When I saw your photo book, I wondered if any other photographer took photos of the pandemic in Tokyo and published a photo book of it.

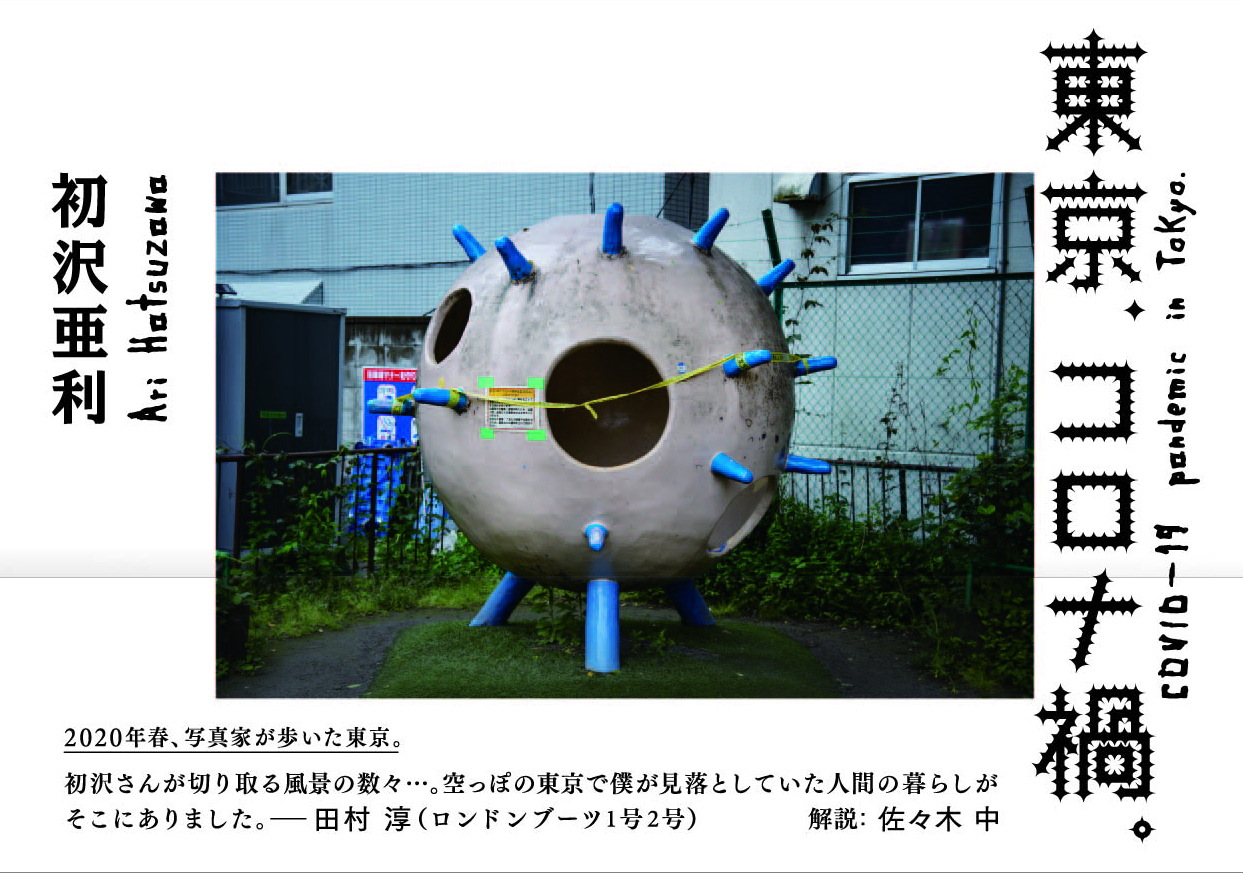

Hatsuzawa: I published a photo book, COVID-19 pandemic in Tokyo, last July, and perhaps the fact that I did it so early was significant. There are thousands of cameramen in Japan, but very few photographers. Looking at social media and such, I felt like no one was taking photos of Tokyo under covid—from the lens of capturing society and the times. I had no choice but to do it myself.

Someone has to document the times, and if no one else could do it, then I had to do it. No one asked me to take these photos. However, I started to develop a sense of responsibility, which drove me to continue shooting for the past two years.

——The Diamond Princess, extensively covered by the press, was featured in your photo book. Was it a deliberate decision for you to go and take photos of it?

Hatsuzawa: I believe this was a combination of me as a photographer and someone who sees society through a journalistic lens. I had a feeling that it was better to take photos of that moment in the pandemic, so I went there of my own volition. Only people in the media with armbands and I were there at the scene. Out of the photos I took, there’s one shot, also featured in my previous photo book COVID-19 pandemic in Tokyo, that feels like me. Standing a little far away, I took a photo of media people from all over the world surrounding the first woman who got off the Diamond Princess in hopes of interviewing her. The sight of this media scrummage was utterly strange, and it felt critical to me. The fact that the crowd became my subject might mean that my perspective is different from others.

Show up aloofly and take photos boldly

——How do you personally think the psychology of people in Tokyo has shifted over the past two years?

Hatsuzawa: As I mentioned before, the number of covid cases isn’t proportional to people’s fear level. I came to realize this gradually. I don’t necessarily agree with people who protest that there’s no need for masks, but at times, I believe it would be more beneficial for us to remain a little calmer. You could say that, in general, the fear of covid has become too normalized. Perhaps, the people I’ve taken photos of were calm in that sense. People who stay at home don’t go outside, so naturally, I wouldn’t be able to shoot them.

——Indeed, people who are afraid don’t go outside. This includes the Diamond Princess, too but do you have any photos that stand out to you?

Hatsuzawa: The two women taking a selfie interested me when I took their photo, which was the key visual of my photo exhibition. It might be a matter of my age, though. When I asked 20-year-olds who came to my show about the photo, they just said, “It’s trendy to take selfies like that” (laughs). People my age think there’s no point in taking photos if you hide your face, but that wasn’t the case for these women. They hid their faces but wanted to show that they were there; it’s a fascinating balance between self-consciousness and anonymity.

——That’s an interesting take. I wouldn’t come up with the idea to take a photo of two women taking a selfie. How did you shoot it?

Hatsuzawa: There’s a phrase I’ve been employing lately: aloofly and boldly. I guess I showed up aloofly and took a photo boldly (laughs).

——You’ve taken photos in many different places and situations, such as Iraq, North Korea, and Okinawa. Do you always have the attitude you spoke about right now?

Hatsuzawa: Each case is different. When the Great East Japan Earthquake happened, there was a meaning behind my going to the affected areas. I was at the site the next day of the earthquake, and there were a lot of dead bodies. I had to be fearless and bold, but not aloof. In North Korea, I was neither of those things. It was about processing the guide’s feelings and understanding the meaning behind the citizens’ perspectives. I pointed my camera to people while picking up on those cues with precision. It was technically easier to take photos in Okinawa than in Tokyo. But I felt like Okinawans had a deep antagonism against people in the mainland, so it was tough to face that.

Different modes of expression in monochromatic photos and color photos

——Can you tell me what made you want to take photos?

Hatsuzawa: I joined a photography club at the end of my senior year in college. I was doing some soul searching and looking for something to do, so I gave photography a go. I got so obsessed with it that I almost couldn’t graduate (laughs). At first, I used monochromatic film and took snapshots of the city without thinking much about it. After that, I held photo exhibitions and such. After I graduated, I did a series called “Tokyo Poésie ” in the Tokyo Shimbun. That was my first job as a photographer, but I didn’t struggle so much, and it’s like the photos I had fun taking turned into a series. But when I started doing the same thing with color film, people didn’t like them at all. I knew I had to become a photographer, so I joined a studio and became independent as a “studio man,” and here I am today.

——Is there a difference between shooting in black and white and color, mentally speaking?

Hatsuzawa: Monochromatic photography is about wanting the viewer to pay attention to a particular area and adding contrast. It’s an escape from society (which is composed of color). However, color photographs include miscellaneous things, so many things get in the way when you want to convey one thing. Color photos are about how many elements you want to show can be packed into a shot. I often don’t mix monochromatic and color photos because they’re different modes of expression. However, about 5% of the book is monochromatic.

——You also had a few black and white photos at the photo exhibition.

Hatsuzawa: I got asked why but I just took monochromatic photos because I wanted to. I took a shot of the Hinomaru Driving School in Ebisu. It’s usually bright red, but it was white during the Olympics, like a ping pong ball. I thought it’d be better to erase the color and bring the white tones out, so I decided to use monochrome.

When I didn’t know whether to use color or black and white, I went online to ask people which they preferred. I posted all of the photos on social media as soon as I took them. So, this photo book is composed of photos that I posted and updated on social media every day during the past two years of living in the pandemic, just like everyone else.

The beauty in irony

——I see. When I looked at Tokyo 2020, 2021, I felt it would become even more meaningful over time.

Hatsuzawa: That was the hardest thing about making this photo book. People don’t buy photo books so they can read them a decade later, which is why it’s hard for me to ask people to buy my book now and look at it in ten years. But a parent who just had a son came to the exhibition, and it made me very happy when they said, “Could you sign my son’s name? I want to show it to him ten or 20 years later.”

I believe photographers always take photos while thinking about how they will look once time passes. Everyone takes photos during the pandemic with their phones. Under these circumstances, it requires a preparedness to take photos attached to your name as a photographer. It also means your documentation of the era will remain. I became aware of the role of the photographer once more through this.

——Covid isn’t over yet, but do you plan to continue shooting Tokyo?

Hatsuzawa: I’ve slowed down a bit, and I’m in a bit of a predicament. It’s not like I have a topic I want to shoot next. Maybe I’m getting tired of it. I bought a new camera at the end of last year to see if changing my camera would change my mood, and I felt excited about it, but I didn’t feel like venturing out into the city to shoot as much as I expected.

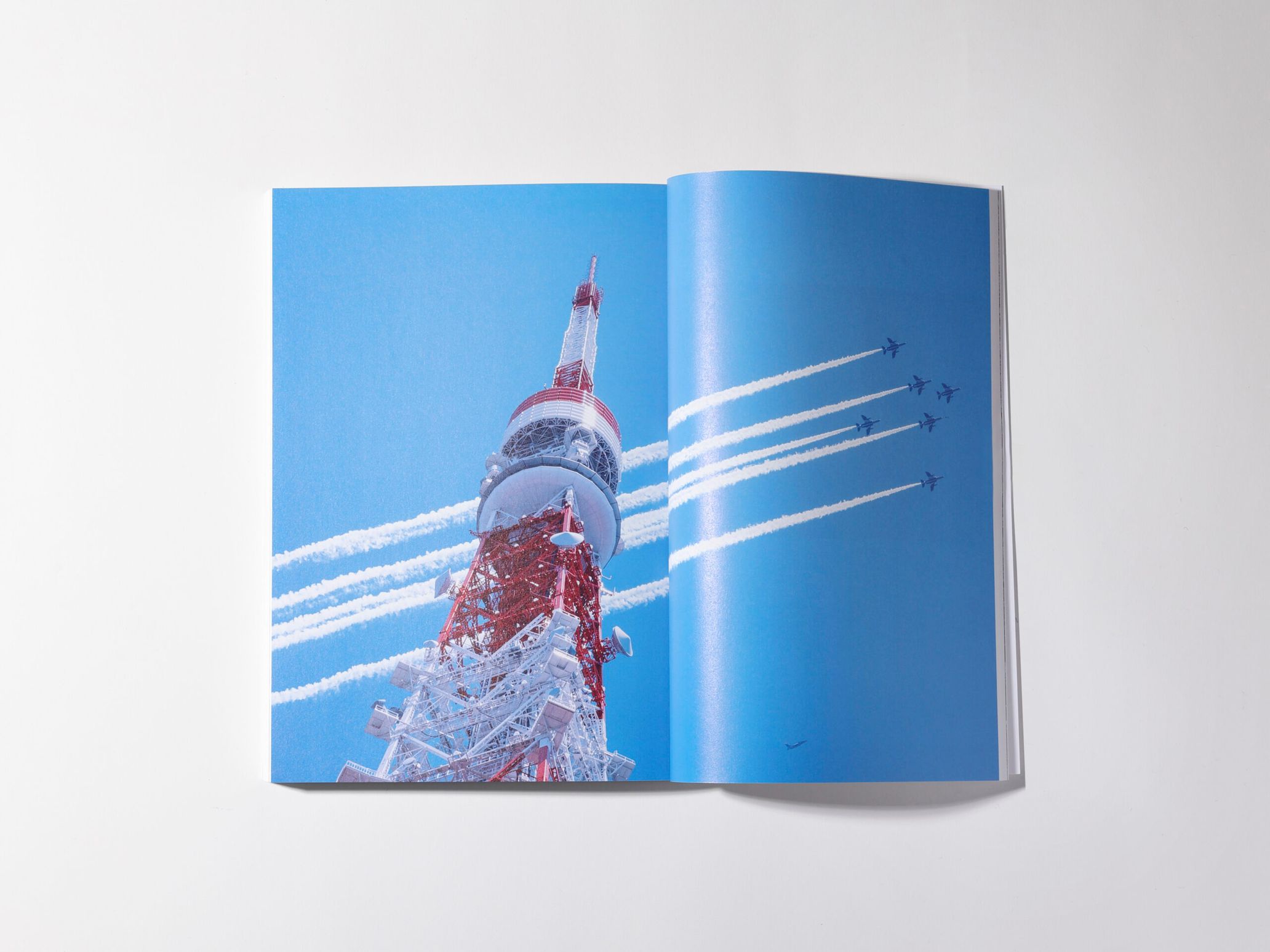

In actuality, I had the idea to take photos of Tokyo in my mind for a long time, but I never did it until recently. As a photographer, it was easy to take photos during the Tokyo Olympics and covid. When the pandemic’s over and Tokyo returns to normalcy, it’ll come down to how I could take photos of the city.

——What kind of city is Tokyo for you?

Hatsuzawa: I still don’t have the answer. I’m a Tokyoite, so I haven’t been able to exteriorize it yet. I feel like I have no choice but to respond to this question through photos. But there’s no doubt that Tokyo is a city where power, like politics and corporations, is concentrated. But it’s hard to encapsulate that power in a photo. Plus, there’s the question of how to shoot Tokyo as it’s changing.

Ironically, not only Tokyo but the Japanese people are becoming more mature. Society’s becoming kinder, and while I doubt that inequality and discrimination will ever disappear completely, they’re decreasing a lot. The streets and facilities are becoming cleaner and more accessible to disabled people. However, wildness, high energy, and obscenity are slowly fading. In other words, we live in a peaceful society, but that doesn’t mean things are photogenic. I don’t think human nature is virtuous, so the [bad side] goes to one’s secret account. You can hide your name, so you could appear kind on the surface but become tainted with anonymity.

——So that’s where the title of your photo exhibition, “Tokumeikasuru Tokyo” (Anonymizing Tokyo), comes from.

Hatsuzawa: Yes. No matter how much society improves on the outside, I figure the ratio of negative and positive emotions of human beings will never change. It’s a universal thing. Additionally, emotions on the surface go underground. It’s hard to shoot things that slip under the surface, but I thought this title would be apt for the two years I spent taking photos of different things. I don’t like to take photos unless they’re beautiful. You have to take them beautifully. Doesn’t irony exist because of beauty? Ironically, I was able to take beautiful shots of society and Tokyo over the past two years.

Ari Hatsuzawa

Ari Hatsuzawa was born in Paris, France, in 1973. He graduated from the Department of Sociology, Faculty of Letters at Sophia University. After graduating from university, Hatsuzawa worked at Iino Hiroo Studio before forming his career as a photographer. He’s the recipient of The Newcomer Award by the Higashikawa Awards, the Newcomer’s Award by Photographic Society of Japan, and the Sagamihara Photography Award (Newcomer’s Award). His photo books include Baghdad 2003 (Hekitensha), Rinjin: 38-do Sen no Kita and Rinjin Sorekara: 30-do Sen no Kita (both published by Tokuma Shoten), True Feelings: Tsumeato no Shinjo (Sanei Shobo), Let us know about Okinawa (Akasha), and COVID-19 pandemic in Tokyo (Kashiwa Shobo).

Twitter: @arihatsuzawa

Photography Shinpo Kimura