Fine art artist Akiko Nakayama’s Alive Painting is literally a “painting that is alive.” She uses water-repellent acrylic paper, Petri dish, sand surface, and other supplies as a “landscape” and drops or pours liquified paints on them; she shares the paintings—or the views orchestrated by various paints—through live performance with the audience. The images constantly change, which makes them impossible to be replicated.

Alive Painting is an artistic conflation of the two major art mediums—painting and performance—and a unique form of creative expression. Nakayama is constantly updating the style of Alive Painting, collaborating with musicians, and adding improvised poems coinciding with the visual.

The beauty of “fluidity” and “colors” she found in her childhood underly in Alive Painting. Nakayama mentions, “After calligraphy class when I was washing up the brushes, I captured the mesmerizing beauty of ink drifting through the water.” She continues, “In calligraphy class, you know how teachers cross out the parts that need to be improved, saying things like, ‘it would look more beautiful if you upstroke here a bit more.’ I got so frustrated whenever they did that. And my patience was wearing thin, but that was when I spotted beauty happening in the sink, where we usually wash dirty things. I found beauty that no one there was noticing, and I realized how your mind and perspective can convert ugliness into beauty.”

Nakayama discovered the art of colors on her excursion one day to sketch plants. “I found a stem that was green mixed with red, and I was sketching it with color pencils. Green and red gradually mixed and turned into an ambiguous color that wasn’t purple or orange—it was a vegetable color. Then subsequently, I felt the raw smell of plants through my nose exuding from the color, and it was so real—That was my significant experience with colors.”

Fluidity and colors—How does the creator view the natural and pleasant beauty that emanates from Alive Painting? We visited her atelier to hear her story.

From the formative college years to the birth of Alive Painting

–So I heard you were always into drawing and also performing. How did they evolve into your current style?

Akiko Nakayama (from hereunder Nakayama): Since I was little, I’ve always felt like I can fluently express my discoveries and thoughts better through illustrations than words. So I drew on a reg. I knew almost nothing about art when I started performing but started a “Karate-art club” with my friends. I only remember vaguely, but I think we were doing Action Painting—painting our bodies with karate-like moves. From this Karate-art club, I’d realized that using my entire body to move the brush and create art and live painting are incredibly fun. I started experimenting with a projector and a camera after I got into an art university. In university, we had a place where various students learning designs in different majors gathered together, exchanged information and inspired one another. There, I got to try out many different gears. During the time, I was wondering if there’s any way I could start something collaborating dance, music, and drawing. Eventually, I formed a trio group with my friends and did live performances outside of school, at exhibitions and friends’ parties. I eventually started doing solo performances and played at jazz live events, which by the way, was a huge turning point in my career.

–What jazz events?

Nakayama: First, there’s sax player Akira Sakata’s event called Heike Monogatari (The Tale of the Heike), and I did live painting there. Art and music share a lot of common languages, like tone and compositions. When improvising, the melodies were infused with colors, and we made the rhythm of the drawing deliberately offbeat or in sync with the rhythm of the music. I found joy in non-verbal communications and doing sessions with musicians.

–Can you tell us about Alive Painting? How do you create the fluidity and the color phenomenons?

Nakayama: I use a turntable for Alive Painting and draw painting on top of it. I create a slope with water on one side, use a dropper or an injector to control the number of drops, create a swirl, warm up the layered paints to create foam…And I microfilm these moments and observe their movements. There’s a manifold of actions happening even in a tiny space, so it would be impossible to follow all the stories happening if I make the space bigger. Each bubble that appears resembles a human, soul, and what not—Each phenomenon is the protagonist. They appear on the 16:9 stage and are out during intermission. It’s important to create a dynamic enabling the audience to keep their eyes on the ephemerality of these phenomena and all the way through until they disappear.

–It seems like you employ not only paints but other coloring mediums. Do you come up with the formulations by yourself?

Nakayama: Yes, I do. For example, the color inside membranes and plumpness of the bubbles vary depending on the shampoos and detergents used. As my painting doesn’t need to be dried, I can try other liquid options not limited to paint, but I don’t use those that are hard to tell what they are. So, for example, I would use Rayu (hot sesame oil) if people can tell, “Oh! It’s Rayu!” Also, I sometimes use vegetable oils, soil, and sand I bring back from my trips to create colors. I can never forget about my show in Bulgaria—I used water I retrieved from the natural spa next to the theatre to mix in the paint. As a result, it turned out magical, like the colors were drifting calmly in ease… I still don’t know if it was from the spa water, the cold winter weather, or because I was feeling relaxed.

What she want to achieve through her creative works

–Were you inspired by any creators when founding Alive Painting?

Nakayama: I think I’ve been inspired by various artists through learning fine arts and art history in university. To me, Okyo [Maruyama] is “the master of new media art.” He incorporates optical techniques for his ink paintings. For example, he employed the unique visual effect of moiré (mesh patterns of silk fabric,) so that depending on the time of the day, as the angle of light changes, the water in the painting looks like it’s flowing, and fishes look like they are slightly drifting. He also implemented a foreign imported lens for drawing. Finally, not to forget mentioning his painting depicting the legend of a carp ascending the waterfall—Carp and Waterfall. He drew the painting with black ink, however, when I saw it, I thought I saw a rainbow. At first, I thought because the art was so profound, I automatically imagined a rainbow in my head, but then I thought maybe Okyo would draw, intending the rainbow to come visible to those who see the actual painting.

–Your ink paintings are mostly monotone. Would you say they’re inspired by Okyo?

Nakayama: Yes. I heard of a phrase, “There are five different shades of black ink.” By using [different shades of] black ink, spaces are born, and colors come and appear in the viewers’ minds. Simply with paper and black ink, it’s possible to draw a trunk of a red pine tree to look red and leaves to look lush green. Plus, there is a wide variety of black ink and paper, and they come in abundant shades, so I’d say they are essentially not monotone. We can draw a painting of a rainbow without using any colors, which I think broadens the potential of artistic expressions. “Alive” in the name is about Kiinseido (works of art brimming with exuberance and elegance); when I’m looking at a painting, I’m looking for its vital force and grace. Vivaciousness and vitality exude from artworks, and time and force can be perceived from brushstrokes,Gratefully, I learn a lot from different paintings.

–So, not only creating unique colors and movements, but you also need to guide viewers to “feel” a particular way.

Nakayama: The audience and I are all in the same place, sharing the same factors like time, humidity, temperature, air pressure, and sound vibration. The water and foams in my artworks are also affected by those factors. I zoom the matters with the camera, which feels like it’s a sensory apparatus that emphasizes the factors and augments our sensory perceptions. It’s a cycle: the artist, the artwork, and the audience all feel the same oscillation that triggers the substances to move, and the audience re-perceives the factor from the visual feedback.

Nowadays, at my solo performances, I use sounds recorded from live shows. Essentially, I was just interested in observing tiny things by magnifying them, but when I participated in Drawing Orchestra last March, the audio crew introduced me to a great microphone. With the mic, the sound of Soda sounds astonishingly clear, and it picks up faint sounds like a pencil drawing on paper and bubbles popping. I thought it might be fun making music out of sounds I make during my performances and of paints flowing, so I play those sounds during my live performances these days.

Chaos during performances and synergy with the collaborators

–When I saw your performance, I’ve noticed you used many different art materials, more than I’d expected. Are there things you always bring to your performances?

Nakayama: There are art materials that are promising and always bring out the best performances. But I don’t do well when I rely too much on these stalwart players. The paints are largely affected by the surrounding air, and chaos is key in performances. So I purposely place the supplies that I often use in a place hard for me to reach and wait for the paints in action to blend. That way, a miraculous moment occurs, like paint A—a color that’s been hard for me to use—and paint B conflict with each other in the beginning but gradually form an epic moment. To create good chaos, I need to make a good pattern that ultimately transcends into chaos.. it’s a repeat of that process.

–I assume accidents are inevitable when collaborating with musicians or other artists. So how do you prepare yourself mentally when collaborating with others?

Nakayama: The colors and round bubbles displayed on the screen may seem abstract, but in a way, the art is merely a mass of particular substances. Some artists interpret abstractly, but some artists conceive a completely different idea. Though, I think the misapprehensions are fun, and it’s the character of this art. So, when I collaborate, I can also enjoy the unsynchronized ideas.

–What are the unsynchronized ideas?

Nakayama: When I did a live show with a musician, that musician said to me, “I want to project a shadow.” It’s impossible to project a shadow with a projector. Our conversation became a bit of a zen dialogue (a cryptic dialogue.) After the meeting, I had eventually decided to draw a shocking pink painting to make the shade of black look darker. The color was my response to the musician’s image. During the session, the two media—the painting and the sound—communicated with their respective technical languages, and sometimes, I would experiment with a color that the collaborator didn’t request. More than a musician can imagine, the paint colors influence the harmony of the entire show, and the sounds also influence the color harmony. So it’s interesting to see all the elements orchestrating the live performance infusing into one and the finished results delivered to the viewers.

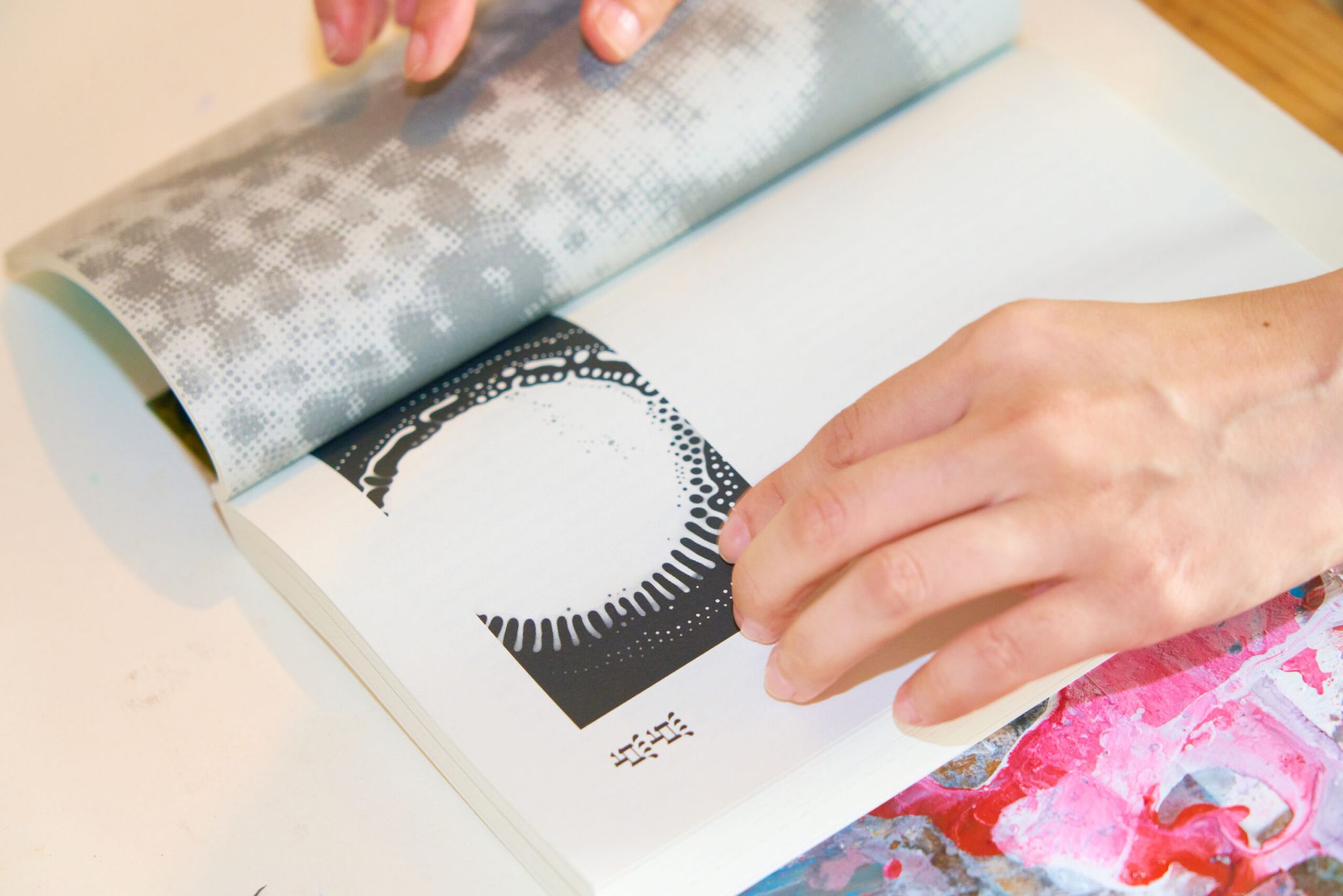

2. illustrations provided to a literary magazine

–You’ve collaborated with the fashion brand Hatra, provided illustrations to a literary magazine, and it seems like you are expanding the scope of your work. Would you say it’s because you couldn’t do many live shows due to the coronavirus pandemic?

Nakayama: There was livestreaming, but I had fewer opportunities to perform with live audiences because of the pandemic. In such time, it was a refreshing opportunity to provide illustrations for a magazine and collaborate with Hatra. The literary magazine was fun observing the grey colors in printing materials formed with dark and light dots and getting to try out different things with my illustrations. With Hatra, the programmer created iconographies and studied the graphics of my works to determine how the colorful threads can be woven to achieve the ink scapes. Of course, the dewiness and plumpness of the original paintings are inevitably lost in the finished products, but still, it was an amazing opportunity to have explored the new always of seeing my works, and I got to see the final forms of my ever-changing paintings through the hand-weaving process. I grew sad from not being able to perform live, but with the collaborations, I got to see the iconographies transform in every step of the process. I felt like I and my artworks were given a new place to respond and communicate, and this made me think that despite the drastic changes in our lifestyles, I could keep my hope up high.

AKIKO NAKAYAMA

Akiko Nakayama is a painter. She orchestrates the energy of colors and their fluid flows to move various substances and create a painting alive. The profound performative paintings are incessantly spawned from her performances, such as the ever-evolving Alive Painting. Her artworks, showcasing fusions and vivacious transformations of various mediums and colors, evoke an improvised poetic aesthetic. The audience immerses in the lyrical landscape as they project their identities and see it as living organisms and nature. TEDxHaneda, Ars Electronica Fes (Australia), Biennale Nemo (Paris), LAB30 Media Art Festival (Augsburg), and MUTEK Montreal are among the performances she has accomplished in recent years.

http://akiko.co.jp

Photography Kohei Kawatani

Translation Ai Kaneda