Culture can be born out of a specific time and place, and yet, it possesses the ability to become timeless. In this series, “時音” TOKION invites people who are shaping culture today to talk about the past, present, and future.

For this article, we interviewed contemporary artist Hiroshi Sugimoto. He is internationally acclaimed for his delicate expression through photography, his use of large-sized cameras, his surreal Dioramas, his long-exposure pictures of movie screenings Theaters, and his series of pictures of the sea and its horizon in different parts of the world known as Seascapes. His repertoire doesn’t stop there: from collecting antique art to architectural designs, recently he has even acted as a director for bunraku and ballet, making him quite the elusive personality.

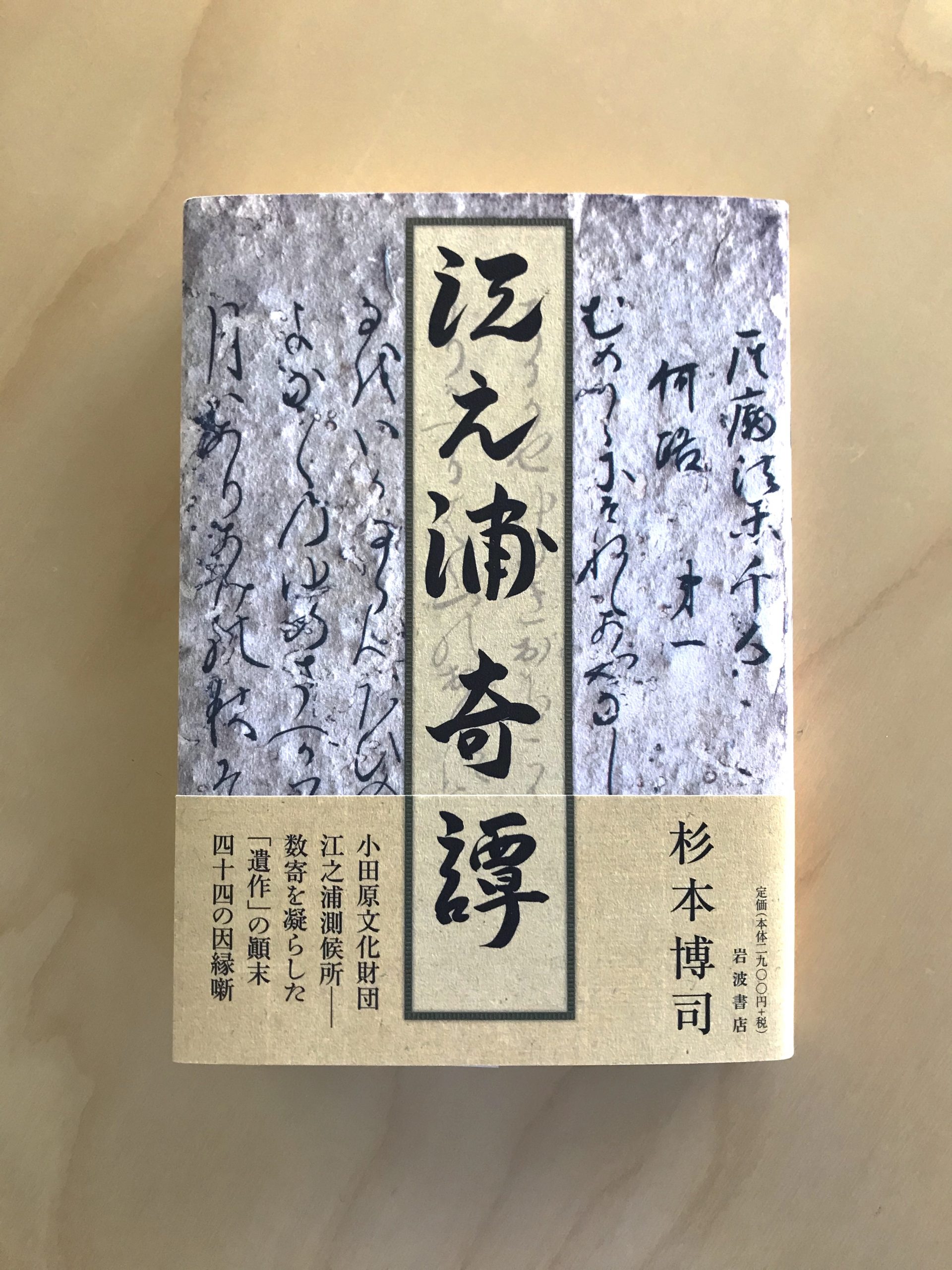

In October 2017, he inaugurated the “Enoura Observatory” in Enoura, Odawara City, Kanagawa Prefecture, which he defined as his “legacy.” The Observatory, which took ten years to conceive and ten more to construct, is a place for sharing Japanese culture, a place to return to the origins of art and humankind, and a pinnacle of his refined taste. In October 2020, he published Tales of Enoura(In Japanese, Enoura’s Mysterious Stories), which contains essays by Sugimoto about the area with photographs. We interviewed Sugimoto at an atelier in Tokyo, during his forced stay in Japan due to the corona pandemic.

――It said in your book that the Enoura Observatory originates from the scenery you saw in Enoura when you were about five or six years old, on the Shōnan train running on the old Tokaidō line; when the train came out of the tunnel, you saw the ocean and realized “you were there.”

Hiroshi Sugimoto: That is my first realistic visual memory. It’s always been inside my heart.

――That reminds me of your series Seascapes, which is also exhibited at the Enoura Observatory. I heard it originates from the question of whether it is possible for modern people to see the sceneries that people from ancient times were seeing; in your childhood, did you feel like you recognized your own existence beyond time and space?

Sugimoto: The perception of my childhood is not so clear, but somehow I feel that the memory of blood can be traced back to the memories before my own life: for example, memories of people in the Jōmon period who were looking at the sea, memories even before that, when apes became humans. Therefore, I think humans have always thought about why they have a consciousness and why they formed a society in this manner, or rather, they want to remember “what a human being is.” I think that’s one of the themes of life.

――What kind of child were you when you were about five or six?

Sugimoto: I used to shut myself in my room and make model railways. There was a maid at home, and my mother was at work; I was a child who often played alone, so I used to daydream a lot, and I thought I was a little different from ordinary people. I used to have visual hallucinations. I think it was around my second year of elementary school: my mother thought that Christian education would be good for me, so I attended a nearby Sunday school in church, and one day, I saw something like a ring of light on the pastor’s head. I thought it couldn’t be normal, but that it was some kind of sign at the same time. I remember it well. I had some other mystical experiences like that.

――Do those kinds of hallucinations lead to your works?

Sugimoto: That’s why I wanted to be an artist: I wanted to take a concrete picture of my inner illusions, to use it as “photo evidence.” I was trying to become an artist, so I went to New York, and while I was wondering what my means of expression could be, I realized there was photography. Nobody seemed to be doing it yet, and regardless of whether it sold or not, I thought I could create something to strike back at the world of contemporary art. So, I tried to do that, and it went unexpectedly well (laughs).

――You designed the Enoura Observatory based on what the world will be 5000 years from now. What do you think the world will be then?

Sugimoto: One of my visions is that humankind will be extinct, and the Observatory will be a historical ruin that no one will be able to see.

――So there will be no people.

Sugimoto: I think that’s probable. You can’t tell what will come of the future, so you have to use your imagination. After all, 2000 years ago, when Christ was born, no one could imagine what would happen 2000 years later. Actually, when the plague epidemic spread in the 14th century and lasted for hundreds of years, we all thought we were punished by God. We really thought that we might go extinct.

――This time, there may be symptomatic treatments so it probably won’t happen, but something new and out of our hands may happen.

Sugimoto: I think there is a limit to how many organisms can maintain their population in a certain environment. Even if the number of amoebas in a petri dish drastically increases, it won’t go over a certain number. Therefore, I think that there is some kind of great providence at work in the natural world, with the power to automatically stop the number of human beings from increasing any further. Environment-wise, we probably reached the limit before the Industrial Revolution.

――On a global scale, that may be the case.

Sugimoto: I’m still not sure why the humankind was born: why have we bizarrely developed such a consciousness in the animal kingdom, invented language, writing, and developed different means of communication? The fact that we invented currency is amazing too. Our faith in it has made this capitalist society so sophisticated that, in the last 100 years, it has continued to grow exceedingly, and without control, is now spinning down a spiral of self-destruction and extinction. The coronavirus comes from that. If you think about it positively, doesn’t it seem like we were given instructions on how to survive?

――Depending on how we control that, we might be still alive in 5000 years.

Sugimoto: A few people might be still alive. There may be a scenario in which a nuclear war exterminates one-tenth of humanity. Well, in the past, people would say that it’s the hand of God controlling the whole thing, but with the modernization of our times, our devotion to religion wavers, and there is almost no need for a god or a Buddha; part of that is probably because of the recent change in human consciousness. I think that human beings can’t produce poetry and art without spirituality. I think that religion will come back to life.

――The Enoura Observatory’s “Winter Solstice Light-Worship Tunnel” is made to look at the sunlight perfectly penetrating the tunnel on the morning of the winter solstice. How does it feel to experience that?

Sugimoto: It’s mystical. The morning sun I saw one year before the opening of the Observatory was the most wonderful. With the West-high/East-low atmospheric pressure pattern, which is common for Japanese winters, the air becomes especially clear, and the view looks beautiful. From the year we inaugurated the Observatory, the winter solstice has begun to shift to January, so by the winter solstice in December, there is still some kind of autumn rain front typical of the end of autumn, which is warm, cloudy and rainy. The earth’s environment has really changed.

――It’s fortuitous that you’ve decided to measure climate change. Now that some years have passed from the Observatory’s inauguration, is there anything else you have noticed?

Sugimoto: Well, after collecting various things, you start noticing how humans are involved in art and the history of its degradation.

――Art’s degradation?

Sugimoto: The cornerstone of the Hōryū-Ji Temple built in the Asuka period has a better shape and has a stronger presence than the cornerstone of the Gangō-Ji built in the Tenpyō period. From Kamakura and the Muromachi period, people started trying to make things easier and less time consuming, which became easier thanks to better technology, but the more that happens, the more we lose mystical images. Eventually, we got to today’s world. That’s why Ōya stone, for example, doesn’t need any kind of machinery to carve and make it look like it comes from ancient times. On the other hand, even without tens of thousands of people cutting and carrying stones, by using bulldozers and backhoes, even a single, even a single artist with limited incom can do it; maybe the fact that it’s possible is both good and bad at the same time.

――Will the Enoura Observatory continue to change?

Sugimoto: Well, I always feel like being on-site, and I’ve been collecting quite the number of things, one after another, like stones and various items. So, it’s more like I’m organizing rather than planning anything. I’m currently planning to build another gallery for antique art. The design is almost finished, so I would like to start construction around 2022.

――It’d be interesting to run into some antiques while out on a walk.

――The tea room “Uchōten” (In Japanese, listen to the rain) is really interesting, and I love the pun in the name (Uchōten means ecstasy written in different ideograms); it gives some sort of effortlessness to the whole thing. How do you feel about puns?

Sugimoto: When they come out, there’s no stopping them (laughs).

――Like when they start connecting more and more with each other?

Sugimoto: Yes, it’s like rhyming.

――It’s like waka poetry. Tales of Enoura contains waka poems for each chapter, and the postscript even ends with a pun*: “Where did you come from, Tales of Enoura?” (laughs)

*The pun is clear in Japanese, since “where did you come from, Tales of Enoura” becomes “doko kara kitan, Enoura Kitan,” which rhymes.

Sugimoto: It suddenly creeps up on you right at the end(laughs). I added the poems after I finished writing the text. I thought it would be perfect to have text, photography and poetry; just like the Holy Trinity. I wrote them in about a week. The idea to write poems actually came from the fact that I participated in a TV show on NHK by the name of “Haiku” in 2016; I also performed some haiku poetry at the exhibition “Hiroshi Sugimoto: Lost Human Genetic Archive” at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum under the alias of “Akkerakan” (In Japanese, “akkerakan” means spacing out).

――You went for a pun there too!

Sugimoto: Most of my poems are, rather than haiku, more like kyōka poems, for which I use a different alias: “Suttonkyō” (In Japanese, “suttonkyō” means airhead). I actually have a lot of books from the Heian period, and somehow I’ve been able to experience that world through them. I can definitely understand how antique art influences me; it’s overwhelming. With such unexpected connections, all of a sudden I made my debut as a poet. And now, as a calligrapher too.

During the interview, there was a large piece of wood in the atelier which had “Pierce the blue sky” written on it. It’s the title of a 「Taiga Drama」 that was announced at a later date. The main character is Shibusawa Eiichi, known as the “father of Japanese capitalism,” and who will also become the new face of the ten-thousand-yen bills. The calligraphy was excellent, written in splendid upward brush strokes, representing Shibusawa’s innovative spirit and the development of Japan’s capitalist economy. Sugimoto, who wrote it, referred to it as an “Daiji na Daiji”.

Edit Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)

Translation Leandro Di Rosa