From business to science, the number of situations in which some people have been advocating for the necessity of art has been dramatically increasing. Although the world has not always looked very different under the influence of the corona pandemic, people’s minds are changing; under such influence, how might everyone’s perception of art be transformed? Gallerists, artists, and collectors are now doing research and trying to predict what kind of art will appear in the post-COVID-19 era.

This tenth installmentof our series Simon Denny, a New Zealand-born, Berlin-based artist who also teaches at the HFBK in Hamburg. He is known for his works that transform technological experimentation into multimedia, interactive installations. In this interview, we spoke with him about the concept of “blockchain” and the role and future of “art.”

Simon Denny (with Guile Twardowski and Cosmographia) funbug.com (1999-2001) reimagined by Guile Twardowski, with Simon Denny and Cosmographia 2021 Non-fungible token ERC-721

Token ID: 13 Smart Contract Address: 0x6ca044fb1cd505c1db4ef7332e73a236ad6cb71c

JPEG Mint date: 17.12.2021

「A number of my NFT experiments in 2021 were trying to work with history, ways of thinking about the past, and how to put things from the past somehow into the present, technically but also aesthetically」

−−In very basic terms, can you explain just what is an NFT work of art?

Simon Denny: The term NFT refers to a “non-fungible token”, which is a technical definition of a kind of unique cryptocurrency token that can permanently link a unique financial value to a digital file in a public registry and record which wallet address creates, sells and owns the digital object linked to it. Functionally, it allows artists access to a network to sell digital files as artworks. The format’s popularity has created a possible audience and market for digital work which, previously, were hard to attain.

−−Is an NFT artwork delivered to the buyer (collector) in the form of a single digital file? What kind of file (video, .gif, or other kind of file)?

Denny: It depends a bit on which way one connects files to a blockchain as to which files can be NFTs. Different blockchains and platforms allow different formats. The “NFT” part really is maybe best thought of as the entry that brings together information about these files on a public spreadsheet, including a link to where the actual file is stored, which is often on another non-blockchain platform. So, technically, an NFT can therefore refer to any file type that one can link to. Some files are easier to view and trade in the current range of popular platforms than others, so jpgs, pngs, svgs mp4’s and simple html files are the most common and popular file formats that work well within existing popular NFT sales and discovery platforms. There are also some NFTs that work within the limited code space in that registry system, on the blockchains themselves, but these are less common.

――How does a buyer pay for an NFT? We read a lot about the relationship between NFTs and cryptocurrencies. Briefly, can you explain what this relationship might be? Is it just a matter of people who like cutting-edge technological advances, such as NFTs and cryptocurrencies, putting these two interests together?

Denny: An NFT is actually itself a kind of cryptocurrency, and both assets are based on blockchains. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ether are “Fungible Tokens”, in that they are also registries that carry pockets of value, but unlike Non-Fungible Tokens, each token is worth the same amount and their values aren’t unique. The example that’s often given is that of a dollar bill vs a painting. Both objects stand in for a financial value, but if you and I each hold a dollar and swap them, then the value we each have, connected to those objects, doesn’t change. One dollar is essentially the same as another – they’re “fungible”. On the other hand if you have a Picasso and I have a Kahlo painting, and we swap them, then the financial value associated with each would also swap – these assets are then considered to be “Non-Fungible”. They can go up and down in value as unique objects.

Also, NFTs are often bought and sold using fungible tokens like Ether. They are part of the same infrastructure, their values kept track of by the same blockchains, so buying and selling them in those currencies is easiest. On some secondary platforms, one can buy and sell NFTs using state currencies like dollars, but often those platforms are just providing a service whereby your dollars are converted into cryptocurrencies as you buy the NFT. At this stage, the largest blockchain for NFTs is Ethereum, and the highest volume of sales is therefore done in its native fungible token or cryptocurrency, Ether.

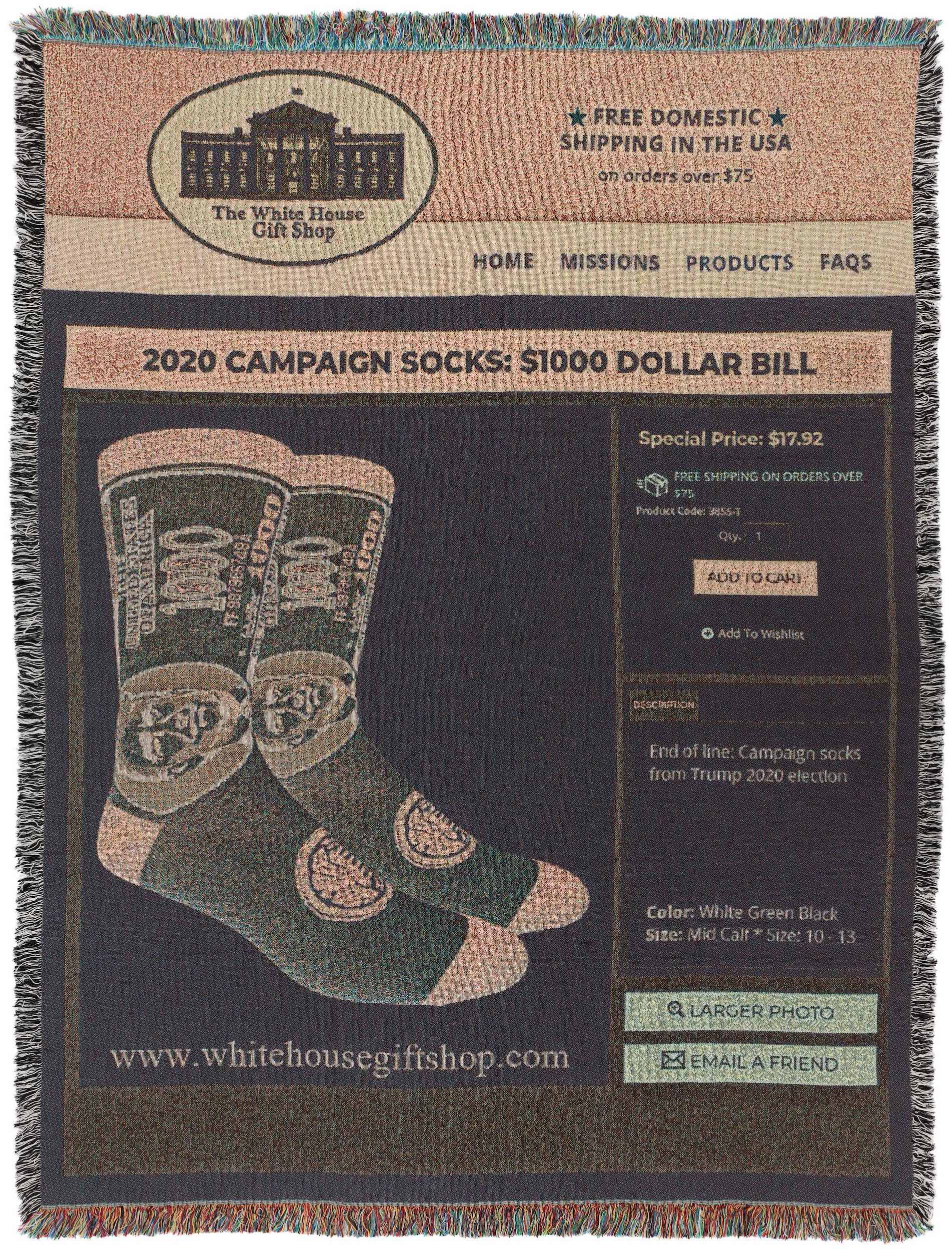

Simon Denny WHGS Meta Throw Blanket – Socks 2021

png, Non-fungible token ERC-721 custom jacquard-woven throw blanket: 200 × 150 cm

Link Voice: https://www.voice.com/creation/100000000019816

−−What are some of the subjects that you like to examine and present in your NFTs, and what is the content of your NFT artworks? Since they are one-of-a-kind creations, we assume that only you (the creator of these artworks) and the buyer of one of these unique creations are ever allowed to see them. Is this correct?

Denny: Firstly, it’s not correct that only the creator and owner can view NFT artworks – it’s exactly the opposite. NFTs, like cryptocurrencies and the wallets that hold them are always publicly visible to anyone who can access the internet. This is one of the key claims of blockchain. Anyone can also see who bought or holds or creates which NFT and when and how much they have been sold for. One of the interesting things is exactly this – that people are willing to pay high amounts to claim ownership over an NFT, but viewing them, and in many cases even reproducing imagery from NFTs, is possible for anybody to do. In some ways this is not so different from, for example, a public artwork, which is viewable by anyone, but is owned by a private person or a state. Often donors who give money to make large public cultural objects happen will also be acknowledged with a plaque saying they did this. That’s a bit similar to how ownership of NFTs work – anyone can see the artwork, but they can also see who owns it.

I have made a number of different NFT-based projects – some which look at the way value transfers through different forms and materials, and others that have looked at the history and aesthetics of the internet, and into time. A number of my NFT experiments in 2021 were trying to work with history, ways of thinking about the past, and how to put things from the past somehow into the present, technically but also aesthetically. NFTs and blockchains mess with time. Events are forever timestamped into a permanent registry, which itself as an event has a duration and temporality to it as a process. Approving transactions and entries on blockchains involves waiting and a social process of approval by communities of human-led and automated systems. It’s complicated, but also poetic. So I wanted to revisit the past of the medium. In a collaborative project I did called Dotcom Séance I tried to reflect on the medium of the internet, and reinterpret and resurrect both ideas that came to prominence through that medium, and also aesthetics that spread through the use of it. Business ideas on the internet often repeat themselves, but within different technical and social frameworks over time. What didn’t work in 2001 might actually work, with a different team and a different technical paradigm in 2010. Ecircles.com (1998-2001), for example, was an image sharing social network allowing users to share photos to friends in closed groups. Quite a similar business model to Instagram, apart from the closed groups and the lack of mobile cameras connected to every phone. I chose a bunch of businesses, like Ecircles, that collapsed in 2001 and worked with AI image maker Cosmographia with their clip+diffusion models to produce possible logos based on descriptions of 20 such companies. I then gave those outputs to Guile, who was the artist behind the first ERC721 (NFT) token project to really scale, Cryptokitties, and he produced a version of one of each reimagined company logo based on his favorite AI output. Pets.com is maybe the most famous of these companies, and became a kind of icon for the 2001 Dotcom crash. I thought especially combining that with Guile’s work was an interesting confluence of internet histories – the undead ideas of the internet past, the first wave, reimagined by today’s most advanced machine learning image makers and an icon of what is becoming referred to as web3, or the crypto/blockchain enabled web.

――Do you ever exhibit your NFTs in art galleries or museums, or how, when, and where do you share them publicly with general audiences?

Denny: Yes I’ve shown NFT and crypto works in museums and galleries as well as online, where they’re visible in the platforms and marketplaces I worked with, like https://www.dotcomseance.com/ , https://folia.app/ , https://opensea.io/collection/dotcom-seancehttps://superrare.com/artwork-v2/nft-mine-offset:-ethereum-kryptow%C3%A4hrung-mining-rig-21644 , https://nft-mine.com/work/0/, and other sites. As digital files in a network, where the networked aspect and the market aspect is part of the medium, viewing NFTs online on such platforms makes the most sense, and is where most viewers who are interested in NFTs and crypto art view them. The biggest of these sites of course have much larger publics than any museum can have. However, I also see value in working with this kind of art in museums and gallery spaces. Translating these works into spatial and material versions is something I’ve done often. Some NFTs I’ve made even have objects connected to them anyway, and a collector is shipped an object when they buy the digital component of the NFT. An example is this series on another platform called “Voice”, which was a series of rugs and images of those rugs I created. A screen grab was made of range of rugs offered by the “White House Gift Shop”. The screen grab was then jacquard-woven into a new rug, photographed and minted as an NFT. The collector that bought the NFTs was also sent the physical rugs. I am also designing a series of canvas print versions of parts of the Dotcom Séance project for a museum in Rome and another in Denmark, which will have art historical allusions in the way they’re printed and installed.

I’ve also curated exhibitions of other artists work that works with NFTs and crypto, such as Proof of Work at the Schinkel pavilion in 2018, and in 2021 an exhibition that brought together artworks from the last 40 years that addressed property and technology at the Kunstverein in Hamburg, including special NFT and crypto projects.

. Both of these exhibitions included projects by artists that work with art and crypto between objects and digital work, and were very physical in their materiality and placed a premium on spatial experiences for viewers – one with an artwork that literally burned cash and issued crypto, and another which presented a marketplace of technological objects selected by academics with a token component.

There are still other moments when digital works have been presented in museums on screens. In this case I prefer to use custom shaped screens, squares (as most of my NFT digital assets are square). It’s often a little less interesting like this, but they also work well, and there are many screen-based exhibitions of NFTs that happen in gallery and museum spaces.

Installation View, Proof of Stake – Technological Claims, Kunstverein in Hamburg, 2021

Photography Fred Dott

「I would personally connect the history of conceptual art to a canon describing where we are with NFTs」

−−What is the price range for your NFT artworks? Are they always sold in auction settings or are they sold in a conventional gallery context, with a gallery setting an asking price for each artwork?

Denny: I’ve done both auctions of expensive works, in collaboration with both legacy art galleries and auction houses, and larger collections at lower fixed prices sold directly on NFT specific platforms and websites. All of these options are possible, and have their merits. The model that feels more “native” to the medium is the one I used for Dotcom Séance, where there are a few hundred artworks in a series sold at a low initial price (the equivalent of a few hundred dollars). This way new collectors and other artists with maybe a smaller budget can buy in and also access the network that emerges around projects that use this sales structure. It tends to create wider support networks for projects, a group of followers that have a stake in the narrative of the overall project and the other collectors as well as their individual work. In this series also, the artworks were organized into smaller groups, and some of those groups then started private channels and other projects based on the ideas around those artworks. I think this kind of thing is more interesting than a single sale to a single collector like auction models tend to support. This is something that can only happen with this medium, is a unique kind of connected ownership enabled by the group of artworks and the blockchain’s records of transactions and therefore associations.

−−Insofar as NFTs are unique creations, they share that condition with many other physical works of art that are also one of a kind. However, NFTs could be easily reproduced, since they are digital files, and such files are normally easy to copy. How do you or can you prevent one of your NFT artworks from being reproduced and then circulated among people other than the person who purchases one of these unique creations?

Denny: The short answer is provenance. With the online, universally viewable record of transactions on blockchains, one can easily see which is the file which is connected to the artistic and financial value. Files that are not connected to these registries don’t hold that value, which is social. But anyone can enjoy the artistic or aesthetic qualities of the work in screen grabs or copies of the file – like they can print or photos of paintings or prints. The artistic “aura” so to speak, comes from the social value, the place in the network. Because it’s networked artwork, in the best case, artwork designed for networks as a medium, if you remove the asset from the network, its just not the work anymore, it’s like a memento or souvenir object.

――Do you see much of a future for this kind of artwork or do you think that it might just be a temporary fad?

Denny: Well I can’t see into the future, but crypto is bringing so many new people to art via NFTs, and indeed to conceptual, network-based art which I see a lot of value in and relevance to the world we live in. I think it’s likely that some things that crypto has built, in terms of infrastructure, will last. And I also think that the existing wealth that has its value in crypto is too integrated into general economies already for it to just disappear, so that will keep the value of NFTs in place to some degree in and of itself. Financial value is a buffer for caring about art, whether digital or otherwise.

−−The history of NFT artworks is still rather short. Still, to date, do you find that NFTs tend to address certain kinds of subjects or ideas in particular? What are some of the common subjects that NFTs address or examine?

Denny: Well it depends on where you start your art history and who’s building the canon you’re referring to. Computer generated art, if you wanna start there, has at least a 70 year history so far, and net art of the 1990s is a very deep and rich body of work, with actors that now work within NFTs. I would personally connect the history of conceptual art to a canon describing where we are with NFTs, as I would with abstraction and machine-inspired avantgardes of early modernism. And I mean in terms of subjects or ideas that art made with NFTs tends to address, I’m not sure its all that useful a frame to think through this with. NFTs are about everything, and nothing, like other forms of art.

Born in New Zealand, lives and works in Berlin and has participated in numerous international exhibitions, including the 2015 Venice Biennale and the 2016 Berlin Biennale. In 2017, he had a solo exhibition at OCAT in Shenzhen, China, in which his three installations explored blockchain, the core technology behind the electronic currency bitcoin.

Photography Max Pitegoff & Calla Henkel

Edit Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)