Ryu Okubo is an artist who provides artworks and produces music videos for artists from eclectic fields, including D.A.N., Mndsgn, Gen Hoshino, and Benny Sings. He started creating animated music videos in 2011, but recently he has been dedicating his time to his own crafts — the embodiment of his personal sentiments.

He was opening his first solo exhibition, Struggle In The Safe Place, in six years at the art gallery PARCEL, exhibiting the works he has rendered in the past three years. We spoke to the artist to learn about his thoughts and emotions embedded in the slew of his works of sequential art, and his creative roots.

I wanted to recreate the atmosphere of my atelier, where I always craft things, in the gallery

――I see a lot of cardboards here in the gallery, but are they part of your works?

Ryu Okubo (Okubo): Yes. They are actually made from wood.

――What are the meanings behind these cardboards?

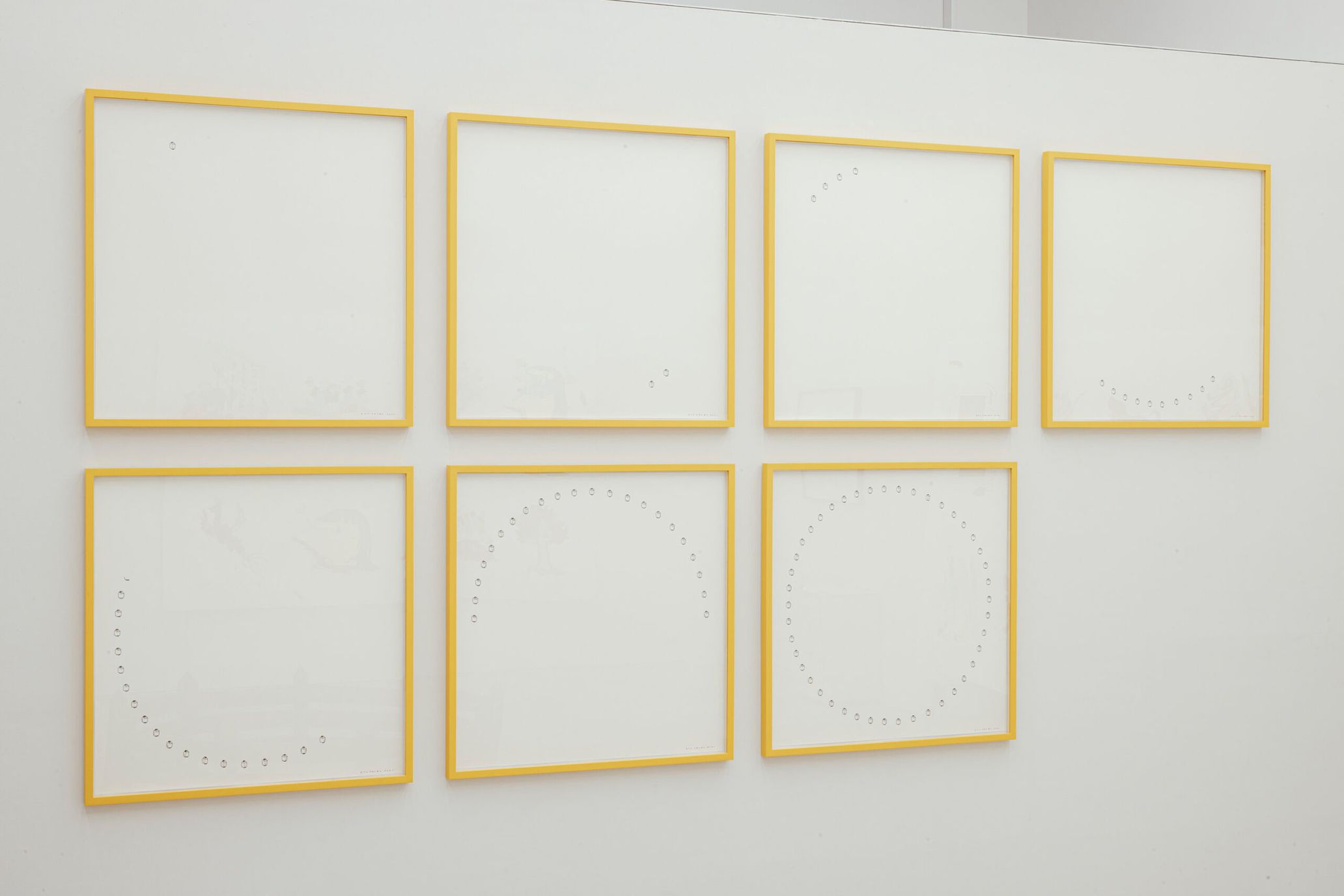

Okubo: There’s not a particular meaning, but my works are a self-portrait in a broad sense, capturing my daily life and moments of myself and also my family, wife, and kid drawing pictures. In relation to the idea of portraying the lives around me, I whimsically thought it would be a good idea to recreate my atelier in the gallery. So I placed my cabinet where I usually put paints and a big canvas against this small aluminum ladder. I also made a Roomba-like object, not that I wanted to make something fake, but I wanted to recreate the things I have in my atelier. Also, I made masking tapes from wood and placed them all over the floor as is in my atelier.

――Do you use masking tapes for your works, too?

Okubo: Not so much for my works, but I use them for almost everything — from when sketching to putting up pictures on the wall. They come in handy.

――Also, I see a lot of palings in your works, and there’s even a paling installed in the gallery. Is there a deep meaning behind it?

Okubo: Yes indeed.

――I’d like to know.

Okubo: Essentially, it represents the main theme of this exhibition and the title, Struggle In The Safe Place.

This also links to the idea of the self-portrait I spoke about earlier — When I draw myself, I can observe myself from a different perspective, and from the way I stand, I can tell that I’m concentrating and working hard on my crafts, which often impresses others. But when I think about the world, I feel Japan is a safe place, and it makes me wonder how I would look from a broader perspective working hard but in a blessed environment. I’m not denying myself, but it makes me question my existence. I guess I feel a bit of shame, too.

I can’t yet deny myself and quit drawing, so I want to use this inner conflict and express it in my art. So, I created this paling to confine myself inside and see my family’s world expand. Also, this paling represents a safe zone or somewhere protected. So, the paling can be construed in multiple ways, but for me, it represents my atelier, home, or in a broader sense, how Japan looks from the world.

――I see. So, in other words, would you say your feeling of guilt or shame is spawned from yourself focusing on crafting?

Okubo: In my case, yes. I’m not sure, but I assume it’s a feeling that everyone harnesses in their own way.

――I think so, too. It’s not like we’re socially withdrawing, but if you take a look at the world, it’s so different that it makes you wonder if you’re really living your life right.

Okubo: I agree. I often feel incapable as a single being but have this restless feeling of wanting to make a difference in the world. I have this momentum, but at the same time, I feel intimidated, and it’s making me jitter.

――So, are the art pieces placed outside the paling representing the things in the outer world?

Okubo: That’s right.

The interpretations of the illustrations have become more complex since covid

――I heard it took about three years to complete the works displayed in this exhibition, but were you affected by the pandemic at all?

Okubo: The pandemic made me reassess whether the place we’d always thought was safe was really safe. Everyone was equally endangered by covid, but there were inequalities where some died from it, and some didn’t. In other words, although everyone had their own safe place, they were not equally safe…. So due to the unfair circumstance, I feel like the interpretation of my illustrations has become more complex.

――The world has changed and turned into a so-called ‘with coronavirus’ society, but is it influencing you in any way and bringing change in your drawings?

Okubo: I wouldn’t say it’s not affecting me at all, but I’m not drawing anything that specifically depicts the circumstance. I’ve been ruminating more over the universally unresolved inequality, which, as I mentioned earlier, has become more complex during the pandemic. So, as a result, I think the way people interpret my art has changed. I feel like some imagine covid from my art depending on their perception.

――By the way, do you think the preparation period was long or short for you?

Okubo: To me, it felt really long.

――Perhaps, three years is long. But why do you think you were able to dedicate such a long period of time for the preparation?

Okubo: I didn’t spend the entire time solely for the preparation, though. For the past ten years, I’ve been doing a lot of client works and collaborations, like making music videos and record art covers for musicians. I enjoyed doing these works, but I was also eager to produce my own artworks.

Creating music videos and getting inspired by songs is fun, but it’s difficult to infuse my ideas into them, which could be a bit frustrating at times. At one point, I felt pretty accomplished with client works and thought it was about time to turn my ideas into real-life artwork. I started focusing on my works pre-covid, from around 2019, and humbly turning down offers from my clients; the next thing I knew, three years flew by.

――It must take courage to decline offers from your clients after you’ve done many music videos and illustrations for them.

Okubo: Yes indeed. Everyone tells me, “I don’t know how you do it.”

Getting the opportunities to work on music videos truly changed my life

――The first work of yours I encountered was Kaisoku Tokyo’s “Kaijyu” music video.

Okubo: That’s quite old. I was still a university student. I was like, 21.

Kaisoku Tokyo “Kaijyu” music video

――I didn’t know you were that young! Weren’t you also in a band called Katakoto?

Okubo: You know so much about me!

――So I found out about the music video you did for PSG’s “Nerenai!!!” quite later. But I thought you were already making a living off your art since you did Kaisoku Tokyo’s music video.

Okubo: I’m really privileged. I’ve been making animations since university, and here I am now. So, I’ve been working as an artist since then; I’m now 33, and I’ve had the chance to produce a lot of works in the past ten years, which felt long. As it’s been a long run, I had a moment where I felt like I’d achieved everything I wanted to do. So I guess now I’m on to the next doing new things.

――Then, looking back, are there works you’ve done that impacted you?

Okubo: Every work has impacted me, but I think PUNPEE asking me to work for his music video has changed my life dramatically.

PSG “Nerenai!!!” music video

――I heard he reached out to you directly out of the blue, is that right?

Okubo: Yes. He saw the animation I made on YouTube.

――Later, that led you to work for PSG’s “Nerenai!!!” music video. I heard that the video was made frame by frame.

Okubo: I’m not really sure what frame by frame is…. But I simply drew a picture on each page and flipped the pages to create the animation. The video is about five minutes long, so I basically had to make a five-minute-long comic book. But this is how people used to make anime in the very beginning. Including the background, I had to draw everything on each page.

――That’s insane. You must’ve ended up with so many pages!?

Okubo: Because of the enormous pages, we couldn’t use CG. I still have the original, so I can flip the pages and enjoy the video anytime. Back then, I had no idea about editing. I just assumed it would work out if I drew the scenes and filmed them.

――That’s like wild guessing and forcing it to work….

Okubo: It was just like that. But I believe in the beauty of serendipitous works.

It’s a single illustration, but it would be cool if I could also convey movements and stories of anime

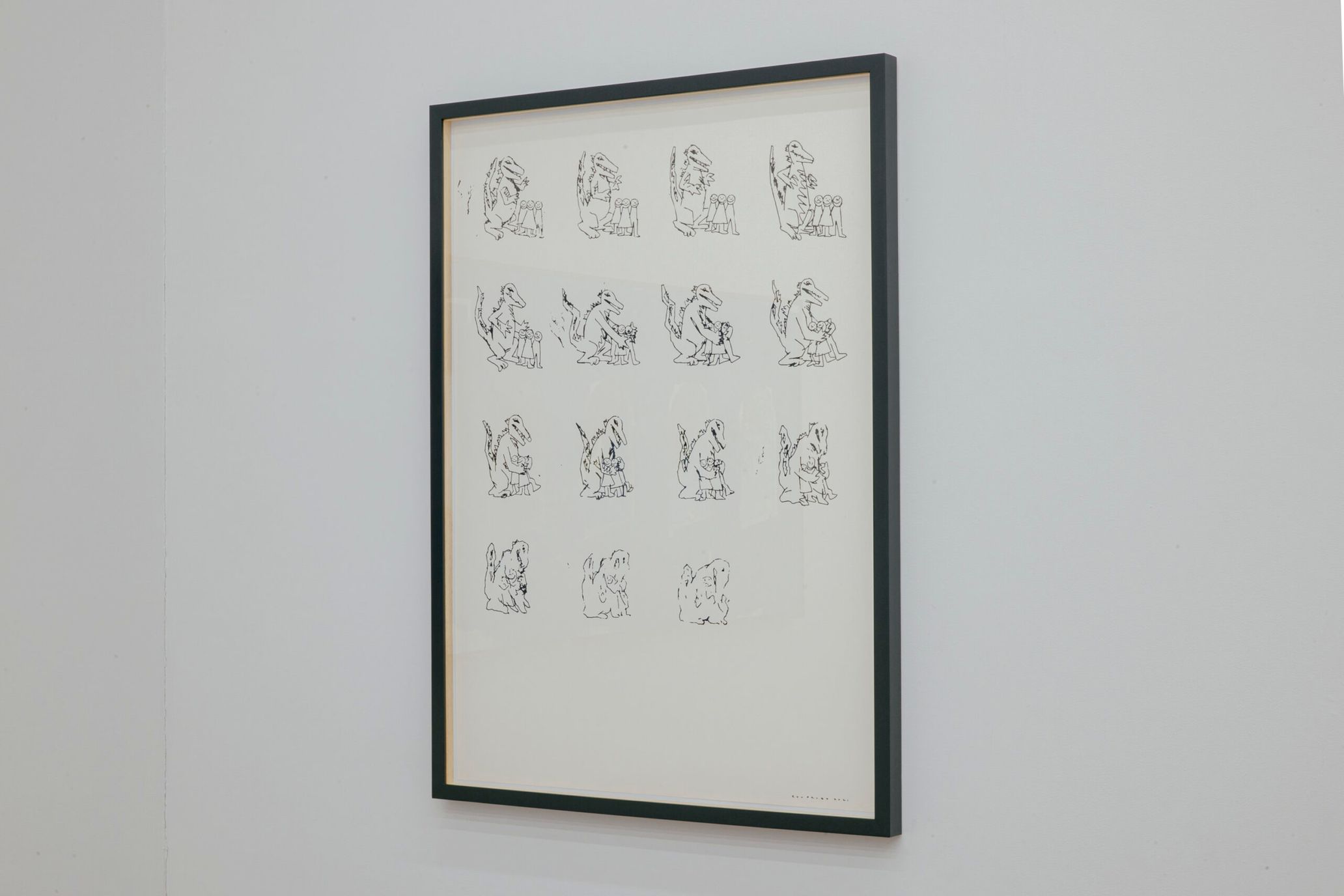

――There’s the word “Sequential Art” in your exhibition note. So would you say your works are in series, like the pages of a flip book?

Okubo: The fundamental concept of my works are all the same. With animation, you need to create thousands or more pages to create a single scene, but paintings are the opposite; you need to portray everything on a single canvas. But I thought I could make something novel if I conveyed movements and stories of an anime in a single drawing. All my works are born from hypothetical ideas like this. Not only with paintings, but I’m also experimenting with different media, implementing what I’ve been doing with my anime works.

――It’s so unique. It’s really charming how I can see the illustrations are in the process of evolving.

Okubo: The monster looks like it’s melting away. I have some drawings similar to this, and they all come from the same idea.

――Now, I’d like to ask you about your roots. Earlier, you mentioned that you’ve been producing music videos since you were in university, but how did you acquire your drawing skills?

Okubo: I’m not really sure how it all started. But since I was little, I’ve always liked drawing pictures, and my parents were understanding of me. Growing up, they told me, “If you like drawing, you should go to an art university.” When I got older, I was still casually into art, so I decided to pursue art and studied and practiced sketching to get into art university. That’s pretty much how it all went. So, essentially, I didn’t have a goal or a strong ambition to become an artist.

――I heard you went to Tamabi (Tama Art University.) What did you study there?

Okubo: I studied graphic design. Well, I was influenced by my mother, who was a packaging designer and does stuff like commercial designs; she advised me, “It’s less chance to make a living as an artist, but if you become a designer, you’ll have more job opportunities.” She always casually told me so, and I was like, “That makes sense. I guess it’s really hard to live as an artist,” and I took her words seriously. So I decided to study designs without thinking too hard about it.

――So back then, you were vaguely thinking about becoming a commercial designer?

Okubo: That’s right. I thought that was more realistic.

I grew up always loving everything that little kids love

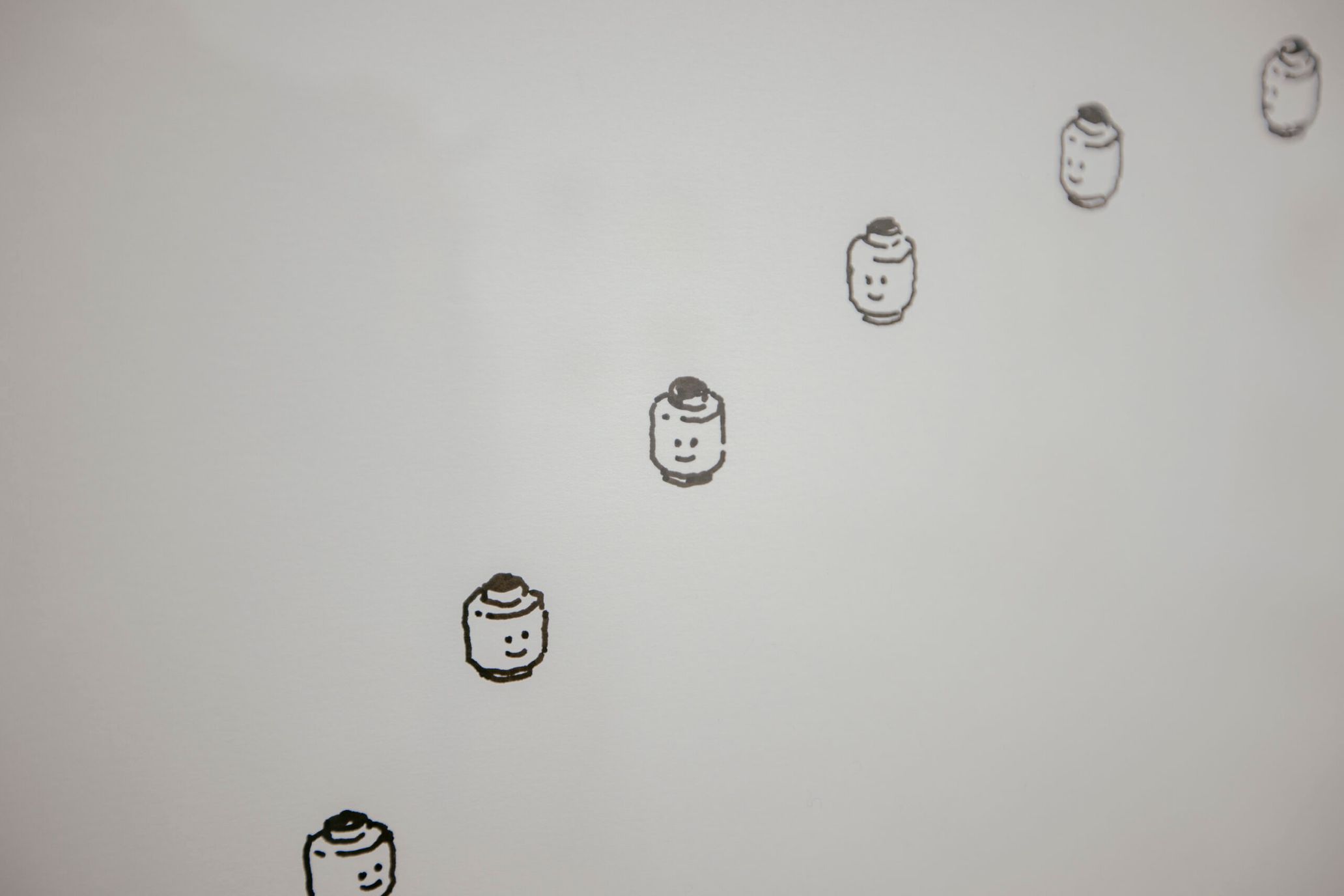

――I see. Shigeru Mizuki and Tim Burton often portray imaginary monsters and ghosts, and dinosaurs in their works. Would you say you’re greatly attracted by these fictional entities?

Okubo: I’m fascinated with how cuteness coincides with eeriness with these monsters. I love this exquisite balance. It’s the same with Yokai monsters. It would be a bit lacking if they were plain cute or scary-looking figures. Instead, I like how they are complex, having two contradictory characteristics. I think this is reflected in my works; the monsters in my works may look cute, but they are also a bit serious.

――I agree. They may seem serious but ‘Pop’ at the same time. I can perceive these two characteristics residing in the subjects you draw. So, when did you acquire your current illustration style?

Okubo: I think my drawing style hasn’t changed since I was little. When I was a kid, I copied the illustrations of Fujio Akatsuka’s Bakabon or round-lined characters from Osamu Tezuka’s illustrations. I think my drawing style evolved from there and eventually turned into my own style. My style comes from various influences, so it’s like a hybrid.

――That makes sense — I can see the influences from Fujio Akatsuka and Osamu Tezuka.

Okubo: Yes. I also love manga from their era. I love manga before Akira Toriyama’s age when the characters were round-ish and cute.

――Yes, illustrations back then were drawn with minimal lines.

Okubo: They’re really simple but deftly drawn. It’s the same with Doraemon.

――Would you say your works are also inspired by music such as Hip-hop?

Okubo: Absolutely.

――Do you listen to music while working and get inspired with new ideas?

Okubo: I wouldn’t say I get inspired with new drawing ideas listening to Hip-hop, but I listen to it when I want to reset my feelings and motivate myself. Not just rap music but music, in general, is a huge part of me. It’s like the source of my energy.

――What’s your favorite music genre these days?

Okubo: What I like now…. I check out new rap music on a reg. I know some people have preferences over rap, but I like all of them. I like its musicality, but also because it’s got a lot of words and messages. I don’t think there is any other music that is expressive, using many words like rap. I do like rock, but it’s more straight-forward. I feel like rock is more lively and linked to the act of drawing.

――I agree. Hip-hop is one of the most expressive genres.

Okubo: It’s unique. It’s music but doesn’t feel like music in a way. You can feel the rapper’s presence up front.

――You can feel their presence, especially from their lyrics. It can only be expressed by them.

Okubo: And that’s what makes it intriguing.

Okubo recently listens to Denzel Curry’s “Melt Session #1 ft. Robert Glasper”

Since my child was born, my time isn’t just for myself anymore

――Other than music, is there anything else that inspires your art?

Okubo: Ah, there’s so many that I enjoy various things. For example, I like to pick up famous works that everyone knows, like Snoopy and Doraemon, and read their originals and try to decipher the authors’ intentions. They may seem like they’re not worth a read as they are too famous, but so many interesting ideas are hidden in these works. So, I try to study from a variety of works and get inspiration from them for my own works. If you also look at major entertainment works like Star Wars, you will discover many clever details. The ideas from these works are also embedded in my works.

――You wouldn’t know how deep Doraemon is until you read it.

Okubo: When I was little, I wasn’t interested in Doraemon as it wasn’t eerie or anything like Shigeru Mizuki’s works. But when I read it later in my life, I was blown away. I felt this profundity hidden behind its Pop-ness — it’s all over in the illustrations and the story.

――I absolutely agree with you. Do you think you will continue projecting the qualities of Pop-ness or cuteness in your works as we see in this exhibition?

Okubo: I’m not sure. But I think those are essential qualities for my art as long as I’m sincere to myself and my work. These qualities are what define me, including the quality of cuteness. I sometimes want to be seen as a poised person, and as there are many different types of people, I get influenced and start conceiving an ideal alter ego. But I think it’s ultimately important to be true to myself, accept who I am, and embrace the qualities that make me, including that Pop-ness.

――You’ve accomplished multiple works, including your solo exhibition and both your personal and client works — so what would be your future goal?

Okubo: I want to do everything if I have the time. But since I have a child now, my time isn’t only for myself anymore — if you know what I mean. I love spending time with my child, though. So to both raise a child and work in the best way possible, I want to spend the rest of my life prioritizing the work I want to do the most. I actually think about this a lot, and this is by far the best solution I have. But I would love to produce music videos again if I have the time and chance.

――I understand about your time no longer being only for yourself after you have a kid. It makes you reassess your work style.

Okubo: But it’s worth it. They make you rethink what you really want and want to do the most. And once you know what you want, you just work for it. So it’s like they help you redefine your options in life.

Ryu Okubo

Okubo is an artist who started producing animated music videos in 2011. He has an illustrious career in providing his works to a slew of artists from D.A.N., Mndsgn, Benny Sings, Gen Hoshino, PUNPEE, group_inou, and otherwise. In 2019, he released the picture book, Mainichi Tanoshii, collaborating with Tamaki Roy of Chinza Dopeness.

Photography Shinpo Kimura

Text Ryo Tajima

Translation Ai Kaneda