©Eisaku Kubonouchi

The drawing seems like it is about to move, like it is smiling at me, and I can even catch a whiff of the character’s hair wafting through the air — Eisaku Kubonouchi churns out such realistic line-drawings. Now 36 years out from his debut, Kubonouchi is a distinguished artist who has cultivated his career with a single pencil in hand.

Kubonouchi is best known as a manga artist for his masterpiece, Tsurumoku Dokushin Ryō (“Tsurumoku Bachelor Dormitory”), serialized in Weekly Big Comic Spirits. It has been more than 30 years since the manga came out, so it may seem gauche to unearth the past, when he wrote the story. Ultimately, it should be the reader’s gratification to flip through the pages and read again the old manga as many times as they want. Kubonouchi, however, is the creator who brought such an amazing work into the world. Given the honorable opportunity to meet him in person, I thought I might as well take the chance to be blunt and rattle off all the prying questions I’d always wanted to ask him. There may be things he has been avoiding to think about, or had forgotten already. But by posing these questions, I believe I can draw out his honest sentiments, and deliver his bona fide words to admiring readers.

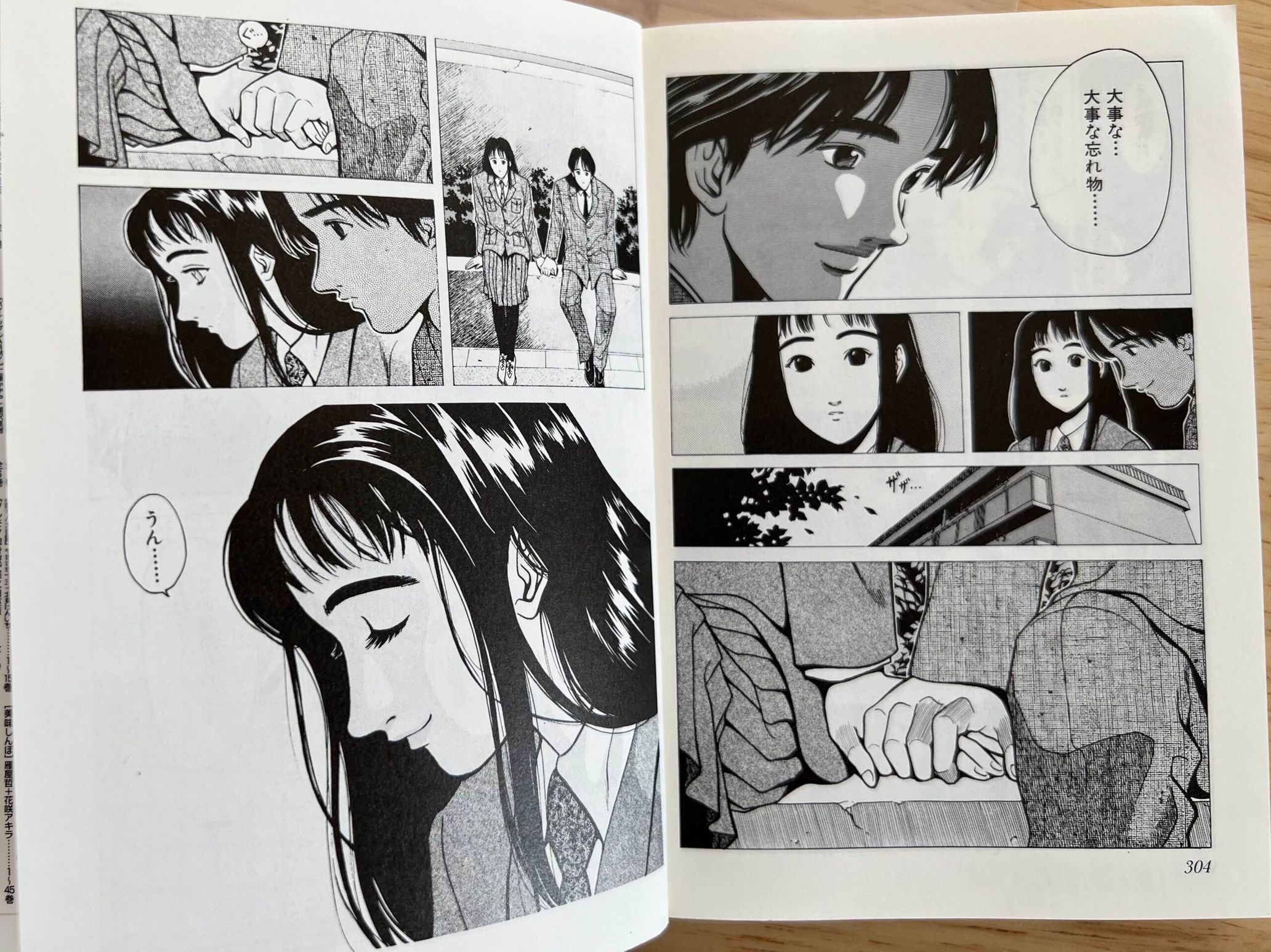

“Yeah…I forgot something here…”

“Forgot something?”

“Something important…I forgot something important…”

“Okay…”

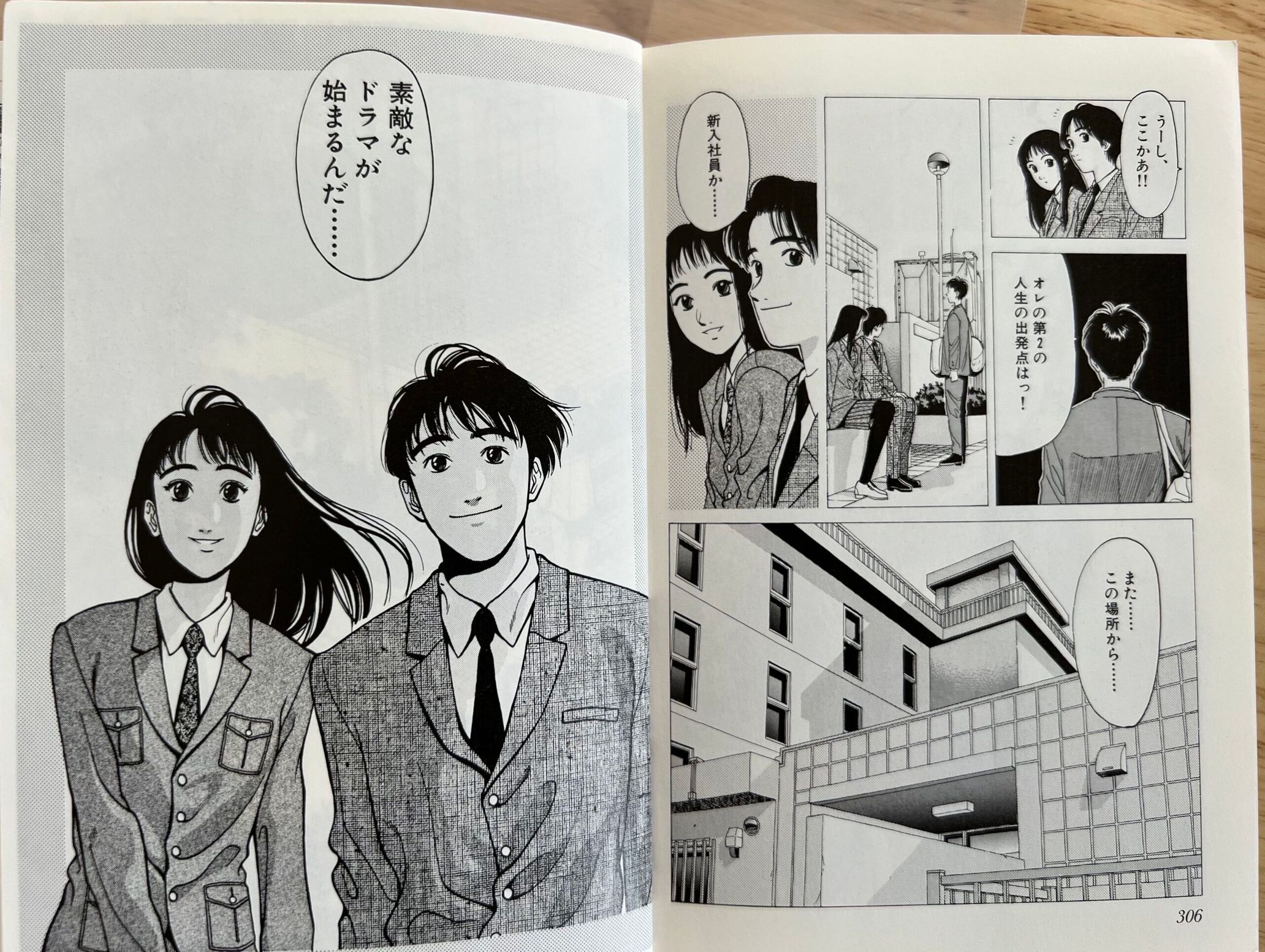

(Alright, starting from here!! This is the starting point of my second life!)

“Ah, a freshman, again…This is the beginning…the beginning of his beautiful drama…”

(From the final episode of Tsurumoku Dokushin Ryō)

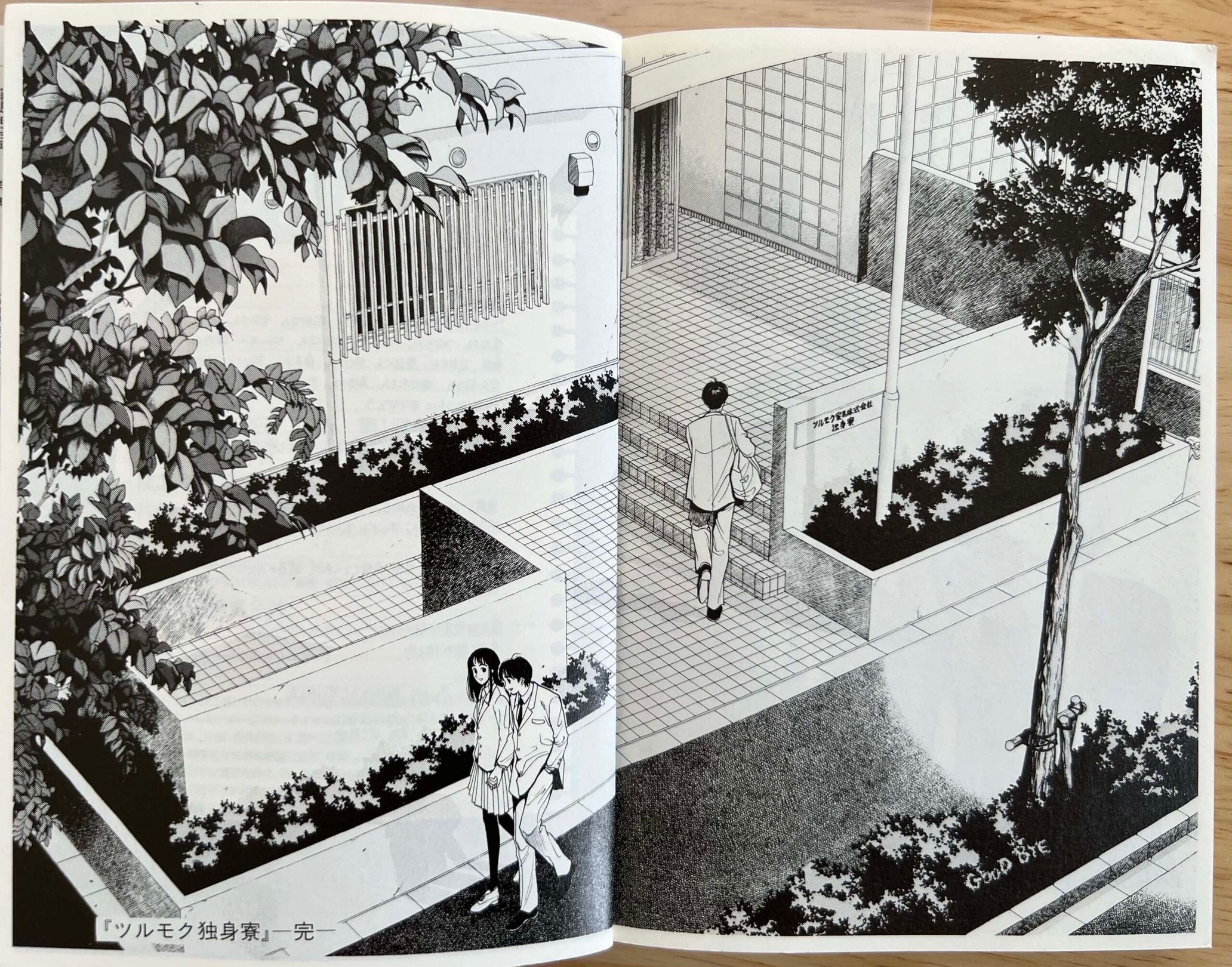

After the conversation, the protagonist Shota and Miyuki leave the dorm holding each other’s hands. As the characters walk off, a freshman enters the dorm. A parting message is faintly written on the shrub— this final scene is portrayed on a two-page spread. It is the first and the last two-page spread of the eleven-volume manga.

I was stunned when I first saw this scene more than thirty years ago. It was the most perfect ending I could have possibly asked for. Since then, I have thought about this last scene every time I make a two-page spread; it has greatly influenced me and my life as an editor. I was blessed with the opportunity to interview my inspiration, Eisaku Kubonouchi, in person.

Tsurumoku Dokushin Ryō

©Eisaku Kubonouchi/Shogakukan

I don’t really look back at my old work

――I read in a previous interview you gave that Tsurumoku Dokushin Ryō (Tsurumoku) becoming a huge hit was a good thing but also an obstacle for you. Do you look back at your most major work?

Eisaku Kubonouchi (Kubonouchi): Almost never. Maybe two or three times in the past, and that’s it. My face blushes whenever I re-read my manga. I’m embarrassed by it.

――Do you remember the stories, though?

Kubonouchi: I remember almost nothing, except that when I was writing, I didn’t feel present in the real world; I was immersed in the fictional world, living every moment in it. Most of my memory from the time is gone, probably because I was too busy and didn’t have enough time to sleep. Once, my assistant told me, “You were passed out with a pencil in hand.” I thought I had only blinked, but apparently I napped a whole hour.

――How about your illustrations? Don’t you at least look back at your recent drawings?

Kubonouchi: Not really. I only look at my past work to look search for any improvements. Even if I did go through it again, I wouldn’t want to look at it too much because it makes me upset— so I focus my attention on imagining what I’ll draw next instead.

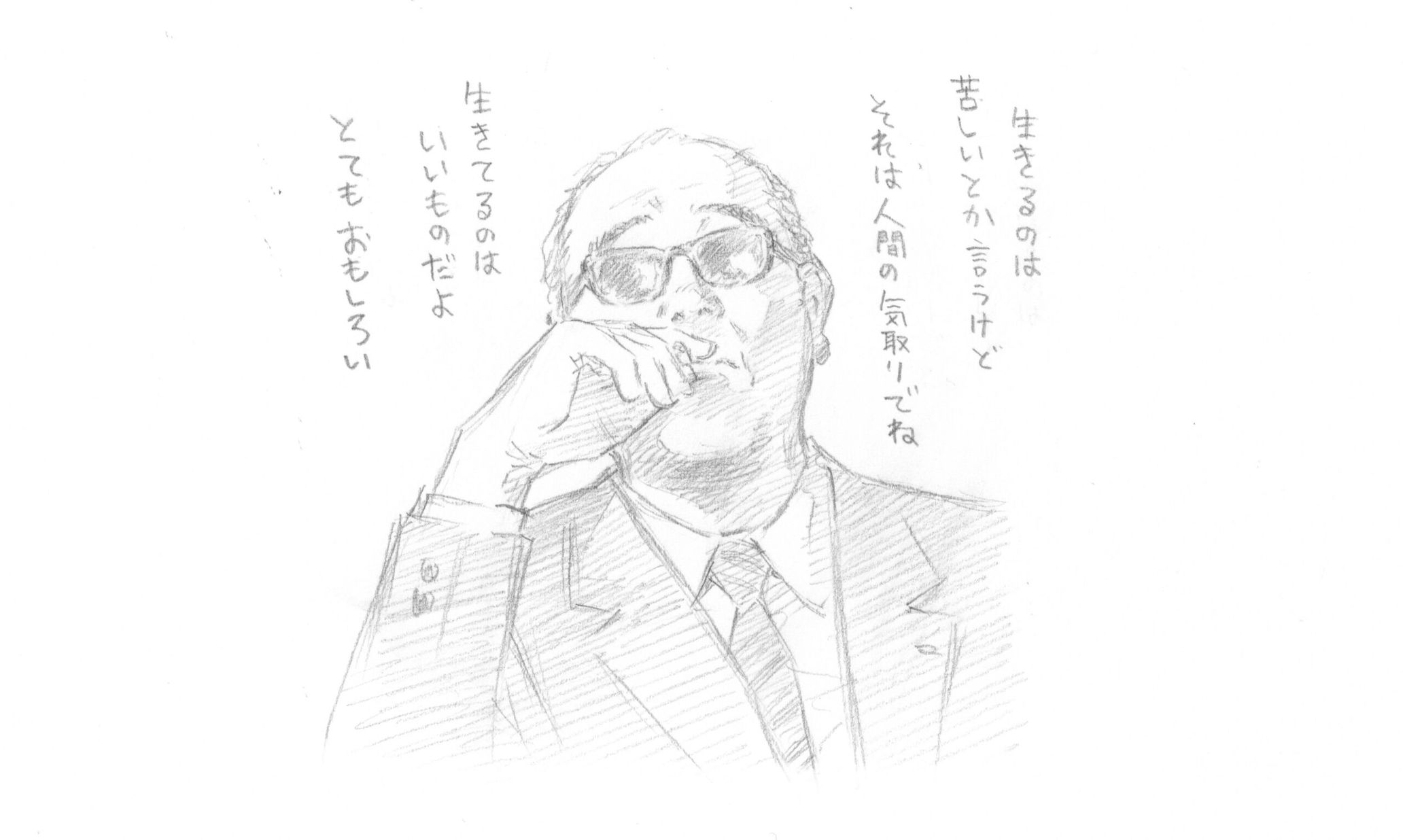

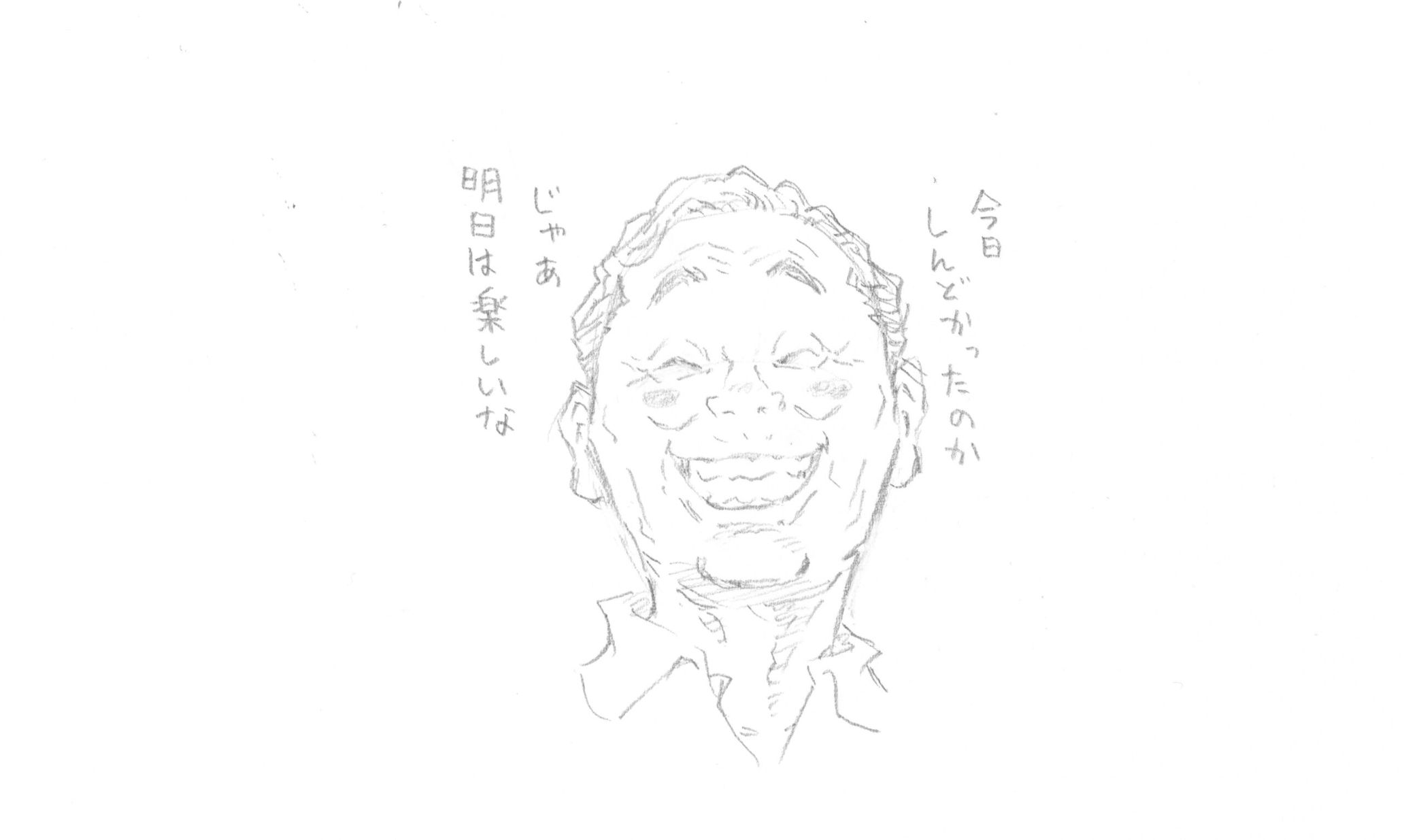

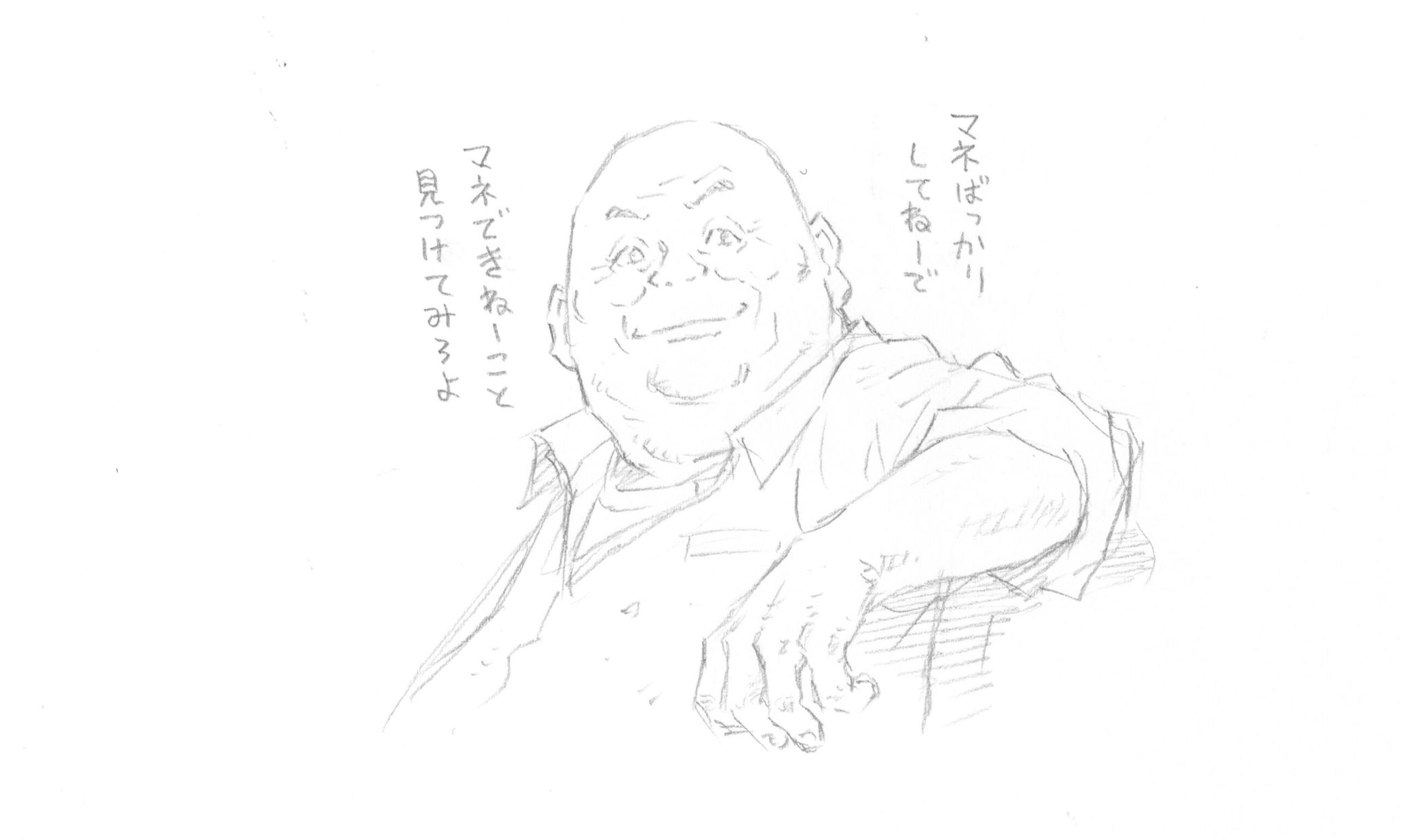

©Eisaku Kubonouchi

All the characters I draw mirror myself

――It’s a shame that you don’t remember much about the manga, but I was following every chapter of Tsurumoku in real time, and vividly remember each single scene. So please forgive me for asking questions about the manga.

There were scenes that showed a character having a peeping habit, slapping his girlfriend, smoking during meetings or while eating, littering cigarettes, pulling down pants and flashing a banquet, endorsing overtime work…I think these were essential to convey the reality of the characters and their workplace [the setting] and the significant contrasts of the story. But nowadays, these types of depictions are difficult to show in a way that would comply with TV or other media outlets. And that’s not limited to manga, I think many films and novels are affected by the restrictions. Since your work remains as time passes, what are the things you’re careful about or keep in mind while drawing?

Kubonouchi: You’re right, one’s work remains in the future. Maybe that’s why I like to compartmentalize myself from my work. I’m the same creator, but I keep a distance and see them like the work of my ignorant youth, when I was a greenhorn. I never deny my works, though. I may be embarrassed, but they’re my creations from the past, and I shouldn’t reject that.

――Michael Jackson and Jesus Jones. A designer suit. Sugi-chan’s hairstyle [beautiful long hair reminiscent of Yosuke Eguchi in Tokyo Love Story]. These portrayals project the trends of the time, like Reiko opening an eponymous restaurant under the concept of “ecology.” But if you read the series now, such depictions may appear dated. I’m assuming Tsurumoku was conveying trends from the day, but what was your life like right before starting the series? Back then, it was towards the end of the bubble era. Do you think the lifestyle and vibe from the time influenced the manga?

Kubonouchi: I was at my poorest in my life during the economic bubble. When the Tsurumoku series started, I lived in a place with a rent of about 20,000 yen. There was no bath, no toilet, and no A/C. It was a bleak room with only a kotatsu [a low table with a heater] all year round. So, as far as I know, I didn’t earn any boon from the economic bubble. Since I was writing Tsurumoku under such circumstances, I depicted trends from two different perspectives: one in a way that the majority of the readers would resonate with, and another from an ironic perspective. Reiko Shiratorizawa was an important character that represented both. Initially, I was drawing her as a parody of hyper-outgoing women in the bubble era, but as the story went on, she gradually ended up becoming cute.

――I noticed that. As the story goes on, Reiko Shiratorizawa becomes more likable as a character.

Kubonouchi: Anyway, I wrote the story from two different perspectives, and that approach hasn’t changed to this day; I depict the positive aspects of trends without forgetting to look at them slightly askew.

――Do you view the characters differently from one other? Are there characters you’re especially attached to, or who reflect yourself?

Kubonouchi: All the characters I depict mirror myself. Tabata, Sugimoto, and Shiratorizawa, for example, each represent a part of me taken to an extreme so as to become an individual character. Even the protagonist, Shota, has a side that represents a piece of me. So, instead of looking at them differently from one another, I look at them all like myself.

©Eisaku Kubonouchi

“The bitterness of wanting to connect with someone but being unable to connect”

――I wonder what would have happened if the characters had a cell phone.

Kubonouchi: It would have been entirely different. What I wanted to convey with Tsurumoku was the bitterness of wanting to connect with someone but being unable to connect. Like a multi-protagonist drama portraying various kinds of bitterness from different perspectives. So if everyone had a cell phone, it would be a different story, and it would be about the exhaustion of being too connected. They would understand each other too well and see each through other too well. There could be a scene where a character finds out about another character’s fake social media account and is shocked, like, “What!? I can’t believe he’d say something like that” (laughs). I guess that could also be an interesting youth story, though.

――Of course! Tsurumoku is a story that captures the complex, at once youthful and mature emotions of a 20-year-old. It also ponders whether dreams of youth are self-contained or something that becomes re-scaled by society. Many of the characters, including the protagonist, Shota, harness such conflicting emotions to show us their different ways of living life. Of all the characters, I find Yasaki and the musician Satoshi have minds that would resonate with young people today. As a young man coming from the countryside to Tokyo to work and walk the road of a manga artist and illustrator, you had probably projected your own dreams onto the characters. What is your sentiment now, after achieving and living through your dreams?

Kubonouchi: The modern world is inundated with information, so young people today are missing out on the perks of being a youth (being prone to indiscretion.) I think these people are extremely clever and smart. Back when I was young, information wasn’t as accessible as it is now, so we just acted on hunches. That impulsive, young momentum was all that I had. And older people around me were forgiving of us young people. But I think that’s not the case for kids today, so in that sense, I feel a bit sorry for them.

――If you were the resident advisor of the Tsurumoku dormitory, what kind of advice would you give to the youths?

Kubonouchi: I would tell them that it’s okay to quit their jobs whenever they like. But only if they are determined about what they want to do in life. I think it takes about ten years to know whether you like a job or not, but you’ll know immediately if it’s something you genuinely want to do.

©Eisaku Kubonouchi

To me, writing manga is equivalent to playing sports for athletes

――Reading interviews of manga artists, I often see them say, “I fell into a such a slump at one point that I couldn’t make it by the deadline and had to halt the series.” I feel like a manga artist succumbs to that feeling as often, if not more often than a pro baseball player. Do manga artists have a constant fear of hitting a slump?

Kubonouchi: I think so. I think writing manga is equivalent to playing sports for athletes. You can’t guarantee that you’ll always hit your best. But if you’re working on a series, you’re expected to perform your best and turn in a masterpiece every week. If the ante keeps being upped, you’ll eventually lose sight of where the benchmark for your potential is. That also leads to Gestaltzerfall, where you lose the full picture and feel like you’re only drawing a piece of an illustration. I didn’t even know what I was doing…. I was at the threshold of losing my mind while Tsurumoku was running— I was so opposed to seeing anyone that I even pulled out the phone line.

――When the manga was remade as a novel, I remember each chapter’s subtitle was “NORUMA” (“Quota”). Typically, chapters are in numeric order or have a subtitle representing the content. Were you calling it “NORUMA” because writing each chapter felt as tough as being forced to meet a quota?

Kubonouchi: That’s right. To me, writing each chapter was exactly like working to meet quotas. Before the series started, I worked for a brand called Karimoku, assembling furniture. Back then, I had a set quota of how many parts I had to assemble in a day, so the word “quota” was never a pleasant word for me. So I think I was feeling so pressured writing the manga that I ended up using the word as a subtitle. I dreaded the idea of writing a series. I still remember the moment I finished drawing the last illustration of the final chapter— back then I was living in a loft apartment, and I remember it was cloudy outside, but suddenly sun beams poured in from the skylight, and the entire room was wrapped in bright light (laughs). In that otherworldly moment, I burst into tears.

――That reminds me of a fable of the monk Kūkai— while meditating at the Muroto Cape in Kochi, your hometown, a beam of light from Venus plunged into his mouth.

Kubonouchi: No way, you can’t compare me with Kūkai— we’re leagues apart. (Laughs)

――What would be the greatest quota you would like to achieve in your lifetime?

Kubonouchi: To make people smile, make people happy with my illustrations. That’s all I could ever ask for. To me, the act of drawing is directly connected to people’s entertainment. People enjoy my illustrations, and I think that’s my quota, or purpose. I don’t want to sound cheesy, but that’s the only purpose I’ve got. I’ve always been like this, ever since I was little; I drew pictures to entertain my classmates.

――After Tsurumoku, you only had four other series, and none of them had more than eleven volumes. I wouldn’t say you are a prolific manga artist. As an illustrator, however, you’ve continued to produce many amazing works, especially line drawings. You’ve continued to draw on a daily basis to this day. But do you ever feel like drawing a manga or writing a story again?

Kubonouchi: Simply put, writing manga requires enormous effort. (Laughs) The process was so traumatizing and petrifying that I even had a physical breakdown. Writing a manga means you have to forget about your personal life and focus solely on writing, which is debilitating. If I began writing one now at my age and current physical strength, I would need to prepare myself with a great deal of commitment.

――But then, how different is it from producing the line-drawings and illustrations you churn out every day?

Kubonouchi: It’s a huge difference. There’s so much thinking required to write a manga. The whole story, the whole world happens all in my head. So I can’t ask someone to help draw any part of it.

――Usually, manga artists have assistants and editors to support them. It’s probably the same with illustrators, too. Which do you prefer, working alone, maybe with a select few talented people, or with a big team?

Kubonouchi: I’d say I prefer working alone — I feel more comfortable controlling the world or story on my own.

Creating a world entirely on your own is the distinction of a manga artist

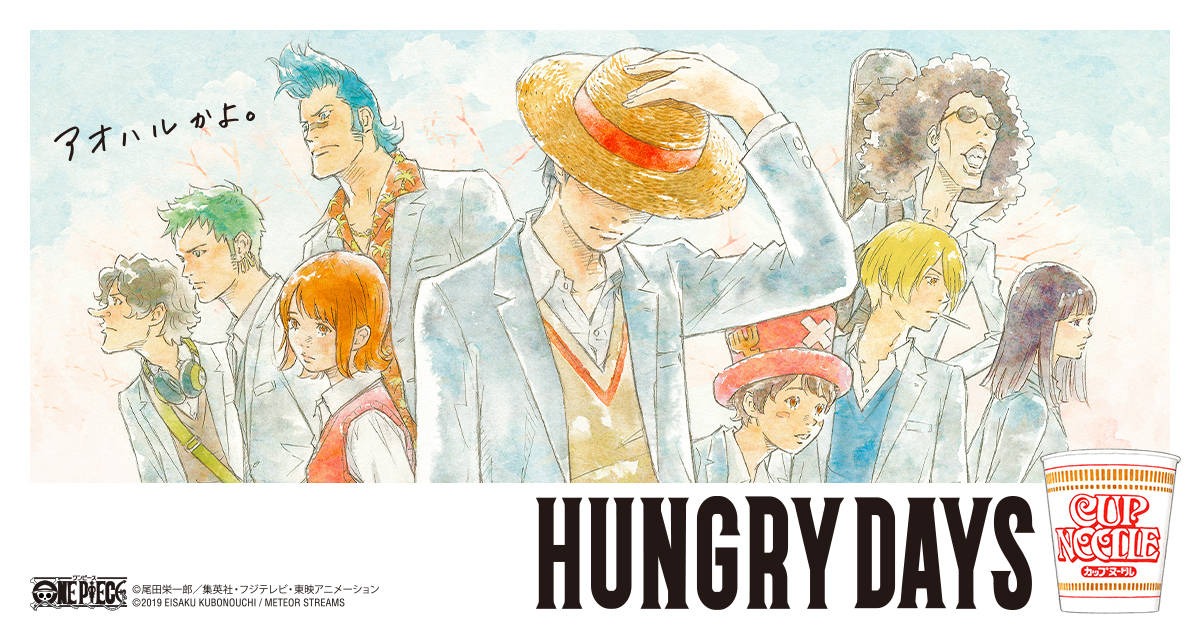

――You’ve done cover artwork for musicians such as Nokko (from the band REBECCA) and RAM WIRE; more recently, you’ve also done character design for a Nissin Cup Noodles TV commercial, the “One Piece Hungry Days” series. I heard that you give small notes and corrections on the creative directions when you do client work. What are the important points for you when doing video work, and how much are you comfortable deferring to others?

Kubonouchi: That’s a good question. I had to learn a lot of this stuff for the first time (laughs). I only started working on animated videos quite recently, and I’ve been working in a style of a manga artist. Initially, I used to draw in meticulous detail, thinking that the characters would move exactly the way I designed. But reality’s different. I was shocked when I saw the characters in motion moving differently than I had pictured in my head. But I came to understand that there are experts working in each section, and I have to compromise at some point.

They may be very rare to come by, but I think it would be incredibly fun if I could work with people who shares some of my sensibilities. I want to meet someone who will excite me, make me jealous, make me think, “Wow, this guy’s incredible. I can’t wait to see what they’ll come up with.” There’s got to be someone like that somewhere out there.

――I’m sure there will be more young people who recognize you through your illustration work. Although you no longer write manga, however, you always say you’re a manga artist rather than just an artist or an illustrator. It seems like you’re stuck to the job title.

Kubonouchi: That’s true. For the sake of creativity, I want to stay a manga artist. Creating a world entirely on your own the distinction of a manga artist. I confront a challenge on paper every single day— it’s my testing ground. I think hard about how far I can recreate the images I have in my head, and how to make a drawing more attractive. So to me, a blank piece of paper is like a boxing ring, or a laboratory. I’m also gradually changing my illustration style day by day, subtly enough that viewers won’t notice. I think you could tell if you compared my current drawings to those from five or ten years ago. I do all this because I strive to draw better and entertain the viewer. And I push myself, like, “I need to improve,” “I can do more,” “I can do better than this.”

Characters designed by Kubonouchi for the Nissin Cup Noodle TV commercial “One Piece Hungry Days”

©︎Eiichiro Oda/Shueisha・Fuji Television・TOEI ANIMATION

If I make drawings that capture human nature, viewers a hundred years from now would resonate with them

――In this digital age, you choose to draw with a pencil and paper. But pencil lines become unerasable once printed. How do you see the process of preserving your work for the future?

Kubonouchi: I’m on social media for the sole purpose of amusing my viewers. Even with small drawings, I think showcasing one’s work is a form of entertainment, so I do it on the principle of entertaining an audience. If not for that, there would be no meaning for me to draw. I don’t want to draw for my own sake. I want to make people chuckle or feel giddy with my illustrations. I try not to get on the bandwagon of negativity caused by the pandemic.

――When I interviewed Hisashi Eguchi, he told me that the only illustration he made portraying the pandemic was of a “girlfriend” [“kanojo,” a recurring motif of Eguchi’s] looking up at the falling snow with a mask pulled down to her chin. He said that he wanted to leave only that one drawing conveying the time.

Kubonouchi: I remember that illustration. I actually drew one like that, too. I drew a picture of a person cutting off the portion of his beard coming out of his mask.

――It almost makes you want to cut it all off.

Kubonouchi: It’s tempting, indeed (laughs).

――There’s one thing I’ve always wanted to ask you directly in person.

There are all sorts of manga, films, and novels in this world with all sorts of different endings. Of all the stories I’ve experienced, Tsurumoku had the most perfect ending. It was so perfect that it left me wanting nothing more. After giving flashbacks of moments in each character’s respective lives, you depict the protagonist Shota’s maturity by drawing him with a solid, thick outline; after awing with that depiction, you follow up by drawing the heroine Miyuki like a spring breeze.

The ending wraps up the hazy vibe of the preceding eleven volumes in the best way possible. When I saw that last scene, I felt it so profound that I couldn’t turn the page; decades later, its imprint on me remains. How long had you been incubating that ending?

Kubonouchi: That much I can remember clearly. I had decided on that ending from the very beginning. When I was told it was going to be a series, I knew it had to end the way it did, and had the whole picture in mind. Regarding the last part, where the protagonist and the freshman pass by each other in front of the dorm, I created that scene considering the dorm itself to be the main character of Tsurumoku. I wanted to make it a story that lingers in the reader’s mind.

――It definitely lingered in my mind. But I’m surprised to learn that the ending had been decided from the very beginning….

Kubonouchi: Thank you. It’s like listening to your favorite song, you want to hear to that comforting melody over and over again.

――Your characters feel like human beings living in the real world, rather than scripted figures. From your perspective as a line drawing artist, what do you feel real people have in common with drawn characters?

Kubonouchi: There’s something I’ve always done since my days of drawing manga: I observe people when I’m drawing people, and try to create a fictional human based on that study. My illustrations aren’t inspired by other illustrations; even if they’re exaggerated or drawn with simple lines, I draw the characters as real-life humans. If I make drawings that capture human nature, I think viewers a hundred years from now would resonate with them. Ukiyo-e is a great example of this. It focused on depictions of real-life human, and so it allows us to discern what people were really like back then. I think it will always be important to draw illustrations capturing intrinsic parts of human beings instead of focusing on the culture or the epidemics surrounding us.

©Eisaku Kubonouchi

――Also, I have a question for you about sound. In Tsurumoku, there are a number of these scenes; the resident advisor Santanda gives a live performance, the phone at the dorm rings; Reiko lapping up clam sauce pasta, workers puffing on cigarettes during recess at the factory; Mr. Ueki’s zipper sliding up and down, catching the light; these scenes evoke such realistic sounds in our minds.

It’s like watching a film with the sounds of shoes tapping, horse hooves clicking or plates clattering. The props in Tsurumoku exude sounds so realistic that I can hear them coming out from your illustrations. Was that intended?

Kubonouchi: I’m happy to hear that. Yes, you’re right, I made a lot of effort to convey those sounds. The sounds we’re able to imagine from pictures and colors come to life from a kind of synesthesia. Line drawings are rendered in black lines, but in real life, there are no such living beings made from black lines. But people can still picture the characters as real humans, and this is possible because we all share this synesthesia. For me, sounds are conveyed by presenting illustrations and laying out panels rhythmically.

Illustrations are kind of like music. I love movies and music, so I guess I’m influenced by them in a big way. I’m also fascinated by the world of poetry. Take Haiku, for example— it’s amazing how it can convey such a vast universe with its minimal five-seven-five syllables. It’s a gorgeous, rhythmic sound. Anyway, I have these images, sounds, and poetry in my head and try to evoke them all in my illustrations. So I’m happy to hear that you perceived sound from my manga.

――Are there any specific sounds that you like? From a movie, or from your own work?

Kubonouchi: Which sounds do I like!? I’ve never been asked that before (laughs). I love music, so I listen to it while working and driving— I need to listen to music all the time, or else I feel like I’m going to lose myself. But if we’re talking sound, rather than music… I guess I like the sound of rain. I love it, actually. I think the sound of rain is a beautiful symphony. So I feel enchanted every time it starts raining. I stop playing music without even noticing when it rains.

Eisaku Kubonouchi

Manga artist and illustrator from Kochi prefecture, born in 1966. In 1986, he debuted as a manga artist with Okappiki Eiji in Weekly Shonen Sunday. His series Tsurumoku Dokushinryo, beginning in 1988, became a big hit. He continued to produce a number of popular manga, including Watanabe, Chocolat, and Cherry. Today, he draws humorous and realistic characters, mainly as line drawings, as can be seen in his book Rakugaki Note. He also provides work for music videos and TV commercials; the characters he designed for the Nissin Cup Noodle commercial “One Piece Hungry Days” have been embraced by youth culture. He continues to make illustrations that pierce the hearts of every generation.

Twitter:@EISAKUSAKU

Instagram:@eisaku_kubonouchi

Phoography Takeshi Abe

Translation Ai Kaneda