Fujii Kaze has been unstoppable since his debut on a major label in 2020. It didn’t take too long for him to go from posting covers on YouTube as an adolescent to releasing original music and gaining popularity from many different people. Even Fujii’s surprise appearance, unbeknownst to the hosts, at last year’s 72nd Kohaku Uta Gassen became a viral moment. Why does his music attract so many people? To learn more about Fujii’s it factor, we asked writer s.h.i. to contribute an essay about him.

Lyrical tricks galore

Fujii Kaze is a curious artist indeed. We can all agree that the quality of his music is undeniable. His musical style may seem quite normal on the surface, but I realized that wasn’t the case once I listened to it thoroughly. The more I think, the less I know. While his melodies are contagiously catchy and easy to listen to, the song arrangements are unusual and elusive, not unlike a nue (a mythical Japanese creature). Anyone who sees Fujii dressed like a fisherman and playfully pantomiming then making finger glasses at the end of his YouTube cover of Ariana Grande’s “Be Alright” will be impressed by his performance skills and down-to-earth coolness. But the question remains: how is Fujii a phenomenon? We’ll probably never know the complete answer. Seeing from his incredible showmanship on Kohaku Uta Gassen and chart-topping new album, there’s no doubt he’ll become a national icon, but no one knows the full picture. I believe he makes us confused at just the right level, which is why he has such an intoxicating magnetism.

First off, Fujii’s lyrics aren’t straightforward. His public image is associated with his dialect, but you won’t hear it in many of his songs. Respectively, only four out of 11 songs on both albums, Help Ever Hurt Never and Love All Serve All, include his dialect: “Nan-Nan,” “Mo-Eh-Wa,” “Cho Si Noccha Tte,” and “SAYONARA Baby” from the former and “Matsuri,” “Hedemo Ne-Yo,” “MO-EH-YO,” and “damn” from the latter. He released five songs as singles, which probably highlighted him as a novel artist and served him well. However, his true prowess lies elsewhere: his excellent wordplay. In “MO-EH-YO,” he rhymes “moeyo” (ignite) with “moeeyo” (that’s enough), combining two contrasting meanings into one word. In “damn,” Fujii uses the “e” vowel to seamlessly connect words in the chorus’ call and response: from “anata e” (to you) to “zenbu” (everything), and from “aosa e” (to blueness) to “semete” (to blame). But we’re just getting started. As if chasing after the first line in the chorus of “Garden,” the second line comes in early with “anatani” (and you). “Soredemo” (still) in the third line comes in a millisecond late, as if Fujii himself feels hesitant. The nuances of his lyrics and arrangements exist in a harmonious symbiosis.

Further, as you would notice if you sing them yourself, the speed at which each lyric corresponds to each note is vastly different according to the song. This difference in speed is especially pronounced in the fluent “Matsuri” and relaxed “MO-EH-YO.” If you think about it, it’s impressive these two songs can coexist comfortably on the same album. Fujii’s music has countless tricks that make the listener stop in their tracks, but because they’re so skillfully executed, it never unnecessarily complicated. Perhaps it’s because of his character, but it doesn’t seem like his music overexplains itself. Instead, I feel like it’s calculated and strategic.

Tracing Fujii’s musical roots and originality through his covers

If you asked me what his strategy is, I wouldn’t be able to tell you. “Lonely Rhapsody” illustrates this well. It might not sound weird because he’s so good at singing, but the way he places the notes and lyrics is unique; the song’s odd structure is closer to Queen’s early music than R&B. Fujii says the following: “I chose the title without really knowing what it means. But the melody progresses at its own pace and in a free-flowing manner, so I think this title was the right choice. I made this song with the desire to stay by the listener’s side while they roam around the streets alone at evening or night.” When I listen to the distinct tone of the Mellotron in the intro and outro with this statement in mind, I picture the curtain of dusk falling from the sky. It fits Fujii’s description. The Mellotron played an integral role in creating progressive rock (think: King Crimson or Genesis) and is an ideal instrument for off-kilter arrangements. The brilliant arrangement in “Lonely Rhapsody” could be associated with different imagery and musical contexts. As I demonstrated, it’s possible to understand his music, but I still don’t quite know the origins of his ideas.

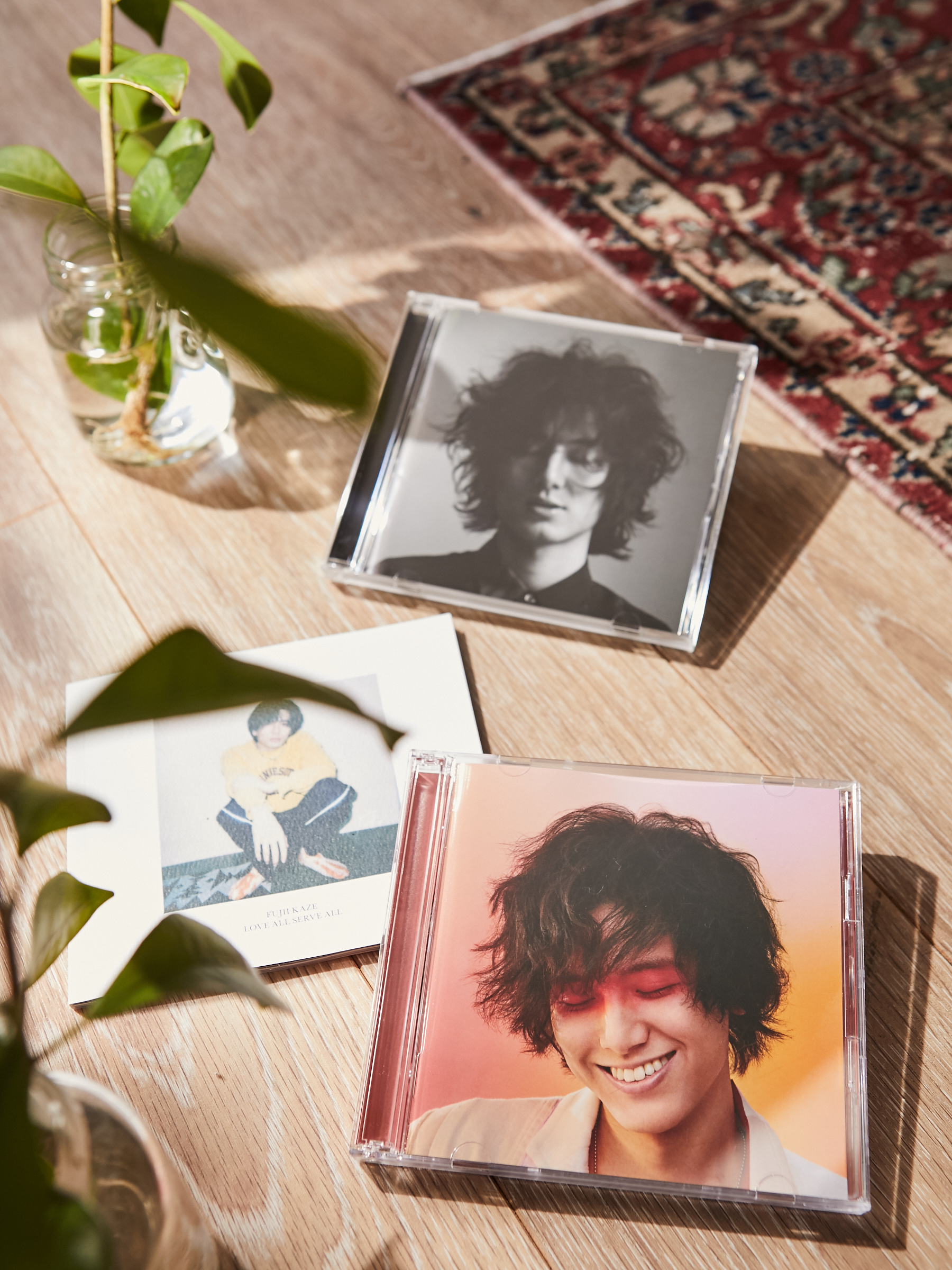

His catalog of song covers in English and Japanese consists of masterpieces from the 70s, 90s, 2000s, and contemporary pop music. Most of the songs—soul, R&B, kayokyoku (a form of Japanese pop music born in the Showa era), and J-pop influenced by these genres—sound familiar and refined. You can see a clear direction in terms of genre. However, it’s unclear whether the songs have a direct link with his music style today. Fujii’s first album exists in the same world as the songs he covered, but in his sophomore album, it seems like he’s heading towards somewhere distant while having one foot in said world. “YABA” is reminiscent of SWV’s “Weak,” which he covered in the first-run limited edition of Love All Serve All, and the off-kilter chord progressions in “Garden” is reminiscent of Stevie Wonder. But you wouldn’t necessarily find the progressive rock inspiration of “Lonely Rhapsody” in his repertoire of covers. The first verse of “Seishun Sick” sounds like an amalgamation of Fujii’s musical roots, and the billowy chord progression in “Hedemo Ne-Yo- — LASA edit” is, without a doubt, unique to Fujii (Mikiki, 2022). His music style is pop, but he has numerous variables that deviate from the genre.

Fujii’s stamp of individuality is a result of his balancing all of the variables. He’s grown by posting covers one after the other like a disciplined spartan, but he’s also taken a conventional route as a singer-songwriter. It doesn’t mean he stays within the lines, though, as he enthusiastically expands his horizons. Further, he can easily collect information from multiple sources thanks to the internet becoming a part of our everyday lives. All this is to say, these things function and fuse through Fuji, a unique black box of sorts. You could say he’s the prime example and outlier of people posting vocal or instrumental covers and songs online for fun. There’s a close connection between what we don’t fully understand about him and what we do, which is why both facets thrive and demand attention. I believe this is where the heart of his elusive appeal lies.

Oxymoronic elements in Fujii’s songs

This essence is also observable in Fujii’s use of words. As embodied by these lines from “Matsuri,” “Umare yuku mono shini yuku mono/Subete ga douji no deki goto” (Those who tare being born, those who are dying/It all happens at the same time), he portrays conflicting feelings with an oxymoronic flair in almost every song. Life and death, first encounters and separation, gain and loss, kleshas and moksha.

He tries to act unaware and eager to learn about these things despite already having confronted them; this is the underlying pattern in his work. It’s truly fascinating how Fujii gets comfortable enough to put off the act and gain illuminating insights. He bobbles around like Kumonosuke Haguregumo from Haguregumo, an animation film based on the eponymous manga series. “YABA” demonstrates this best. Right after Fujii sings, “Nando mo nando mo haka made itte/Nando mo nando mo sono te awasete” (You’ve been into the graves so many times/You’ve prayed to the lord so many times), he uses the slang term, yaba: “Yaba, yaba, yaba, yaba/Kizu tsuke nai deyo/Uragira nai deyo” (Yikes, yikes, yikes, yikes/Then why do you hurt me/Why do you let me down). And yet, his singing and melody don’t make the song frivolous. The R&B-esque luxe vibe is a significant factor. “YABA” shows his (never overbearing) seriousness beautifully.

In his cover of Donna Summer’s “Hot Stuff,” included in the first-run limited edition of his sophomore album, he brings a gloomy tone with an ennui reminiscent of The Weeknd instead of going with the upbeat feel of the song. Seeing Fujii cast a shadow on the lyrics, an illustration of transient pleasures, made me realize he has a “dark” side, not just a “good” side, though he looks overwhelmingly optimistic. I could also tell he carefully leans towards his dark side without being tasteless. It may seem like Fujii goes with the flow and lets his mood guide him, but he thinks everything through. You can’t spot the boundary between his dark and happy side. Perhaps he carries both sides effortlessly, thus erasing that separation. Or perhaps they’re the same, so much so that he doesn’t even think about what separates them. Fujii’s a natural-born trickster who brings complex nuances together and makes the listener absorb them without force. We can’t reach the core of his being, which creates an air of mystery that attracts us to him. Those who hesitate to listen to his music might view his mysteriousness as untrustworthiness, a reminder of how Fujii is a curious artist.

An effortless charisma that captivates people

To describe Fujii in an easy-to-understand manner, his J-R&B-based music, which is spreading worldwide, suits his dual nature well; he’s local yet global and native to Japan and everywhere on the internet. Fujii’s debut with “Nan-Nan,” a song featuring his dialect and internet slang, represents this. This characteristic appeals to his audience both in and out of the country. It’s evident Fujii is aiming for the global stage, as he has English-translated lyrics included in his CDs. They’re excellently translated, with elaborate attention to rhyming schemes. As a listener of his music, I feel that this doesn’t encompass his profound and complex aspects, though. They exist elsewhere. His voice is like an expensive oyster, rich in taste yet pleasant to consume, and no matter how many times I listen to it, I don’t feel bloated, so to speak. He keeps a healthy distance and hydrates us in moderation. This is why we can appreciate his music without thinking too deeply and how uncontrived he is. We accept the beauty of his nuanced expressions before we even know it. Love All Serve All is a manifestation of that, and I have an inkling he’ll continue going in the right direction. I’m excited to discover what’s next in store for this gem of an artist.