Kotaro Manabe has been active in Japan’s outdoor rave scene as a photographer, DJ, organizer, label owner, and writer. If you have been involved in Japan’s outdoor rave scene since the 1990s, you have probably seen at least one of the pictures of the parties he has photographed.

Even though the outdoor rave scene in Japan has grown and become oversaturated, Kotaro Manabe has never sold his soul, and his photographs of outdoor rave parties in Japan during the 1990s and early 2000s have gained archival value over time.

In the past few years, outdoor parties have once again become all the rage throughout Japan, and his photos remind us that Japan has a great history of parties.

Kotaro Manabe

Born in Tokyo in 1969, Kotaro Manabe is a DJ, photographer, and writer. A trip to Kenya when he was in his second year of junior high school led him to get a single-lens reflex (SLR) camera, and since then he has been traveling and taking pictures with his camera. In 1990, after meeting hippie travelers, he became a backpacker and went to Goa, India. There he encountered party culture, and since then he has been active as an organizer, DJ, and photographer, mainly at outdoor parties. Manabe later became active in a wide variety of fields, including interviewing artists, writing liner notes, interpreting, and owning a label. He is also a self-confessed movie buff.

Instagram:@kotaromanabe

Going to Goa with foreign backpackers

——Could you start by telling us how you got started in photography?

Kotaro Manabe (Kotaro): When I was in my second year of junior high school, I was invited by a friend to go to Kenya with 20 other children who had won a prize draw in a campaign by publisher Kadokawa to be part of a movie called “Boys in Kenya.” It was a time when international travel was not that common, and Kenya was a place that I might not get another chance to see in my lifetime, so my mother bought me a nice camera. That was the first time I got an SLR camera, and I think Kenya changed my perspective on life and sense of values. I spent about a week in the jungle, watched over by adults.

——That’s quite an experience. I didn’t know that was where you got a camera for the first time.

Kotaro:But then I noticed that there was a large TV crew there, filming staged scenes with which even as a boy I felt a little uncomfortable. After returning to Japan, they produced TV program “Boys in Kenya: Journey on the African Savanna” with narration by well-known actor Hiroshi Sekiguchi. In the program, they inserted footage of a lion—which we had not seen at all on location—eating its prey, and then added to it the audio of our amazement at a completely different event. Seeing that program made lose my trust in mass media, and it was probably the starting point for the sense of cynicism with which I came to view society, and which I still carry today.

The Strong Sun Moon Festival 『EQUINOX』 (1997) at Nenoue Kogen, Gifu Prefecture

Photography Kotaro Manabe

——So when did you start taking photos at parties?

Kotaro:I guess I started taking pictures of the party scene in 1990. I was working part-time at a bar in Shibuya, and one day on my way home, I saw a foreigner hitchhiking in Roppongi. So, out of curiosity, I gave him a ride and he said, “Take me to the Maharaja Palace!”. It turned out that at the time word of mouth had spread among travelers that the Maharaja Palace was the place to stay when they visited Japan. There was a guesthouse in a suburb of Tokyo called Ishikawadai, which was commonly known as the “Maharaja Palace.” I was shocked to see about 60 foreign backpackers living in a tenement house that looked like a postwar student dormitory. But many of the people there were visually photogenic. That’s when I started taking their pictures.

——In the 1990s, where did most of the backpackers come from?

Kotaro: They came from many different countries. From Europe to South America, there were people from all over the world. That was when I started learning to speak English, but the English they spoke was rarely that of a native speaker. They spoke English with the accent of their own country, such as English with a French or Israeli accent, and I began to think that it was okay for me to speak rough English with a Japanese accent too.

My Japanese friends around me were always talking about the current popular TV drama, so I thought it would be more stimulating to hang out with foreign travelers. Then they took me to parties and said, “Come to Goa with us!” And that’s how it happened. So within a year of getting to know them, I took the cheapest flight available at the time, Bangladesh Airlines, to Goa. That was in 1991.

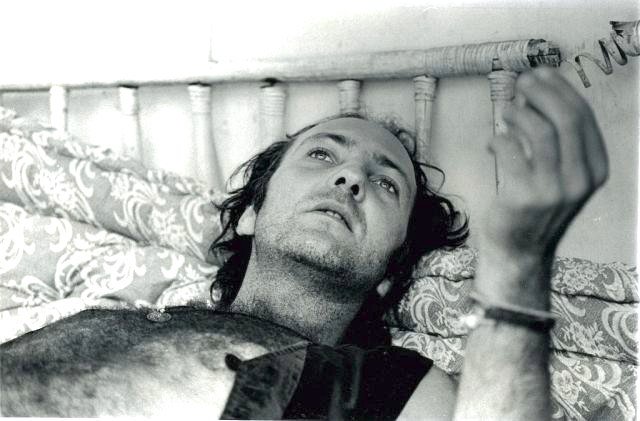

A snapshot of Youth(Dragonfly Records) taken in GOA(1996)

Photography Kotaro Manabe

——What a story!

Kotaro:In those days, many of people staying in Goa were those who had turned their backs on society, so it was forbidden to take pictures at parties. If you were caught taking pictures, they would pull the film out, so I didn’t take pictures of the party itself, but I did take pictures of my friends I was spending time with in Goa.

After returning to Japan, I showed them to my friends who would later organize the “EQUINOX” event with me, and they said, “This is amazing!”. When we started the “EQUINOX” party, people were not allowed to take pictures, but we wanted to document what we were doing, so members asked me to take pictures. As I was taking pictures at parties, other organizers started asking me to take pictures of their parties. I was asked to take photos for Vision Quest, SOLSTICE MUSIC FESTIVAL, Arcadia, anoyo, and others, establishing my position as a party photographer of that era. That was around the 2000s.

——When did “EQUINOX,” which you were also involved in as an organizer and DJ, start?

Kotaro: I think it was around 1993. It is now considered to be one of the first legendary outdoor parties, but it didn’t start out that cool. At first, we had “EQUINOX” at a nightclub called “GEOID” in Nishiazabu. Jun Ito, the organizer of “EQUINOX,” once told me how this outdoor party started. One day, GEOID was forced to temporarily suspend operations. So, in desperation, they decided to have it somewhere outdoors.

At the meeting points such as the Iikura intersection and the entrance to Yoyogi Park, partygoers were given a map of the party venue, and when they finally went to the location indicated on the map, they found themselves in a park in Saitama Prefecture. In other words, the party was held in a completely guerrilla-like, unauthorized manner. Obviously, one of the residents who was strolling through the park at dawn called the police. At the time, my only involvement with EQUINOX was helping to pack my tourist friends into the back of a Toyota HIACE van and take them to the venue, and helping to print the flyer.

GEOID at the time, where the early “EQUINOX” parties were held

Photography Kotaro Manabe

——When “EQUINOX” started, was the sound played at the party Goa trance?

Kotaro:Around the beginning of 1990, I don’t think there was a definition of Goa trance as a genre yet. It was called “Goa techno” or “Goa music” because it was techno played in Goa. At that time, DJ K.U.D.O. (a.k.a. Artman) was already DJing at “Space Lab YELLOW,” but his sound was a bit more like German techno. Residents of the Maharaja Palace, with whom I went to Goa, would come to the club and DJ K.U.D.O. used to call them “Goa people”. Goa was one of the sacred places for hippies, and parties were often held on the beach or in the forest, but the sound there was more like a mixture of techno and electronic body music.

——In Goa at that time, were the DJs travelers or locals?

Kotaro:I don’t think the local Indian people were involved in any of the business content. Ray Castle, who was a little older than me, and others were using Walkman Professionals. In short, they used two cassette tapes to DJ, and they didn’t have any other equipment like mixers, so they couldn’t do mixes (laughs). Around our time, DAT (digital audio tape) finally became mainstream.

And of course there were no turntables because we were having a party in clouds of sand on the beach, and CDJs were not available at that time. In my second season in Goa, I brought my own DAT and a small DJ mixer with me, but equipment was so precious in those days that the organizer of a private party at a hotel villa where Sven Vas performed once asked me to lend him my mixer. TOBY, who was called a techno diplomat, also went to Goa. At that time, Goa was a place where various elements such as trance and techno were mixed together without being bound by genres.

The sound was subdivided more and more in 1993, as I recall. Around that time, trance labels began to emerge from Europe, the first being Dragonfly Records, started by Youth, the bassist of the band Killing Joke. I think that was the first one to be called a Goa trance label. Simon Posford, who would later work under the name Hallucinogen, also worked there as an engineer. I also think that many of the trance artists during that period were originally playing music in bands. Even today, Ben Watkins’ Juno Reactor is a good example of a band unit. Two members of Eat Static were members of Ozric Tentacles, and even two members of System 7 used to be members of Gong. Even Raja Ram is from a band called Quintessence.

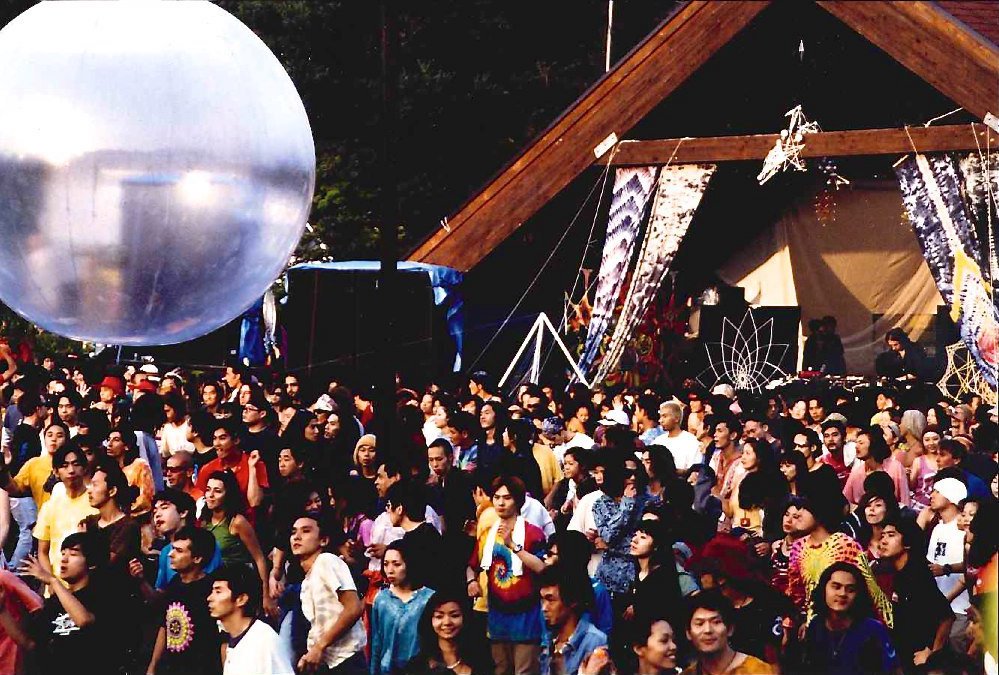

The Strong Sun Autumnal Equinox Festival “EQUINOX” (1999) at Goko Pasture Auto Camp, Nagano, Japan

Photography Kotaro Manabe

DJing with DAT, not records or CDs

——How did people get information about releases?

Kotaro:At that time, music that was not even on CD yet was coming from all over the world to Goa. DJs from all over the world would bring in DAT recordings of artists from their own countries, and everyone would exchange them with each other. When I was DJing in small bars, artists from other countries would come up to me and say, “Hey, you want to trade your music with mine?” The act of exchanging music was called a session. The next day I would go to the DJ’s house, or he would come to my place, and we would exchange tracks. Even though we were at a beach resort, we were just staying in our rooms and listening to music with our headphones on. (laughs).

Then, the track data exchanged with artists from different countries would then be brought back to their own countries, and these pieces of music would be played at parties in their respective countries. The radical people who gathered in Goa became the hub of world music scenes that were simultaneously growing in popularity. Looking back on those days, when there was no Internet or cell phones, and the scene spread only by word of mouth and flyers, I think the world was truly full of energy.

Photography Kotaro Manabe

——As someone who was in the audience at EQUINOX at the time, I was very impressed with that event.

Kotaro:In my mind, there was a clear distinction between entertainment (business) and partying, and we felt that we were “doing a party”. When asked “What is a party?”, an easy distinction for me to explain is whether there is hired security or not. Having staff everywhere with T-shirts that say “SECURITY” on them is not a party in my mind. If something goes wrong, it should be solved by the people there without relying on security. In the first place, people who cause trouble for others, which security has to contain, should not really be at the party.

Later, I became involved in the “Hotaka Sanroku Festival” and “WAKYO,” and in some cases, due to party regulations, we had no choice but to include security. But basically, for parties that are held outdoors, having people wearing security T-shirts standing in front of the stage with their arms folded is not the way a party should be!

——You are saying that if we are going to create our own style, we have to protect it ourselves, right?

Kotaro: So even if people were paying for the party, they were more like “fellow party-goers” than “customers”. Within a small community, word-of-mouth information about interesting parties gradually spread, and our friends invited their friends, and the number of people grew even more. If someone at the party caused a problem, it would really be the people who brought them, not the security guards that really need to deal with it.

In 1997, when EQUINOX held its first 2-night, 3-day camping festival, I was impressed by something an overseas artist said to me. He said, “You can leave your valuables all over the place and go to the dance floor and no one will steal them! Such a peaceful party is only possible in Japan!”

The Strong Sun Autumnal Equinox Festival “EQUINOX” (1997) at Nenoue Kogen, Gifu Prefecture

The Strong Sun Autumnal Equinox Festival “EQUINOX” was held at Nenoue Kogen in Gifu Prefecture in 1997, a three-day and two-night camp-in festival style, following the great success of the previous event, which attracted 1,000 people

Photography Kotaro Manabe

True liberation of the mind and body made outdoor parties possible

——You were shooting with a film camera at the time, right? There were no cell phones back then.

Kotaro:That was a time when there were no cell phones or even digital cameras. Until 2001, when the word “digital” finally came out, we had always shot parties on slide film, but we had to change the film from day to night. So, when shooting with one camera, I would start shooting at night with tungsten film and change to daylight film when the sun started to rise.

At that time, slide film with 36 frames cost around 1,000 yen per roll. Moreover, since I had to get the film developed after returning to Tokyo, I had to wait several days after the party at the earliest before I could see the results. The cost of developing the film was also high, so the cost of shooting alone must have been considerable. Considering today’s digital environment, I have the impression that the burden and weight of the shooting was much different.

——What are some of the most memorable scenes when you were shooting?

Kotaro:It is obvious that artists playing guitar at a show are photogenic, but DJs at that time had an aura of coolness just by being in the booth. But since the 2000s, I don’t take many pictures at parties anymore.

Well, I don’t find any party or DJ booth exciting for me anymore. The moments that I enjoyed taking pictures of have become less and less enjoyable for me. I think the organizers felt this change, and they started asking me to take more pictures of the audiences, and there was a gap between what I wanted to take and what they wanted me to take.

Also, at the time, there was a limit to the number of film shots I could take, so I couldn’t take a single shot without any consideration. Moreover, maybe I was in a good state of tension due to the fact that I had to wait for a great moment and to release a shutter carefully. This may be one of the factors that make the photos of today’s digital age look different from those of the past.

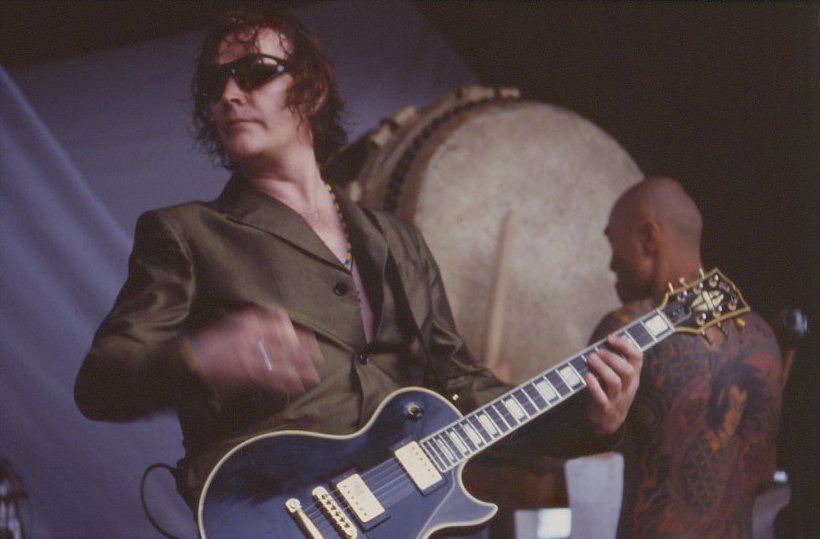

Artists who performed at parties in the 1990s and 2000s, such as X DREAM, Juno Reactor’s Ben Watkins, DJ TSUYOSHI, and Siva Jorg photographed by Kotaro

Photography Kotaro Manabe

——What was it that attracted you to the era you were excited about?

Kotaro:I guess it was the atmosphere. I think people were able to really let loose in those days. Nowadays, sauna is all the rage among Japanese people and they are saying that the sauna invigorates people’s mind and body. But I think people were literally invigorated in parties back then. But even if we tried to do it again, I don’t think we would ever be able to recreate it. That wonderful space was not created only by the organizers. I think it was the atmosphere created by all the people who were there, and it was closely related to the background of the times and the global situation. We may be able to aim for a different form of great space, but I don’t think we can recreate what was there in that era.

I feel that such a scene changed around the 2000s, and it was around that time that the media started to sit up and take notice of those kinds of parties and we received significant media exposure. It was fine for the parties to get bigger and bigger under sponsorships, but I have the impression that the original atmosphere of the parties changed considerably from then on.

——From the late 1990s to the mid-2000s, the outdoor parties that had existed until then began to decline. Do you think there was any other reason?

Kotaro:One of the reasons for the decline of outdoor parties was that they were hit hard by the weather. Unexpected problems and expenses resulted in accumulated losses: at the end of EQUINOX, Goko Pasture Auto Camp in Nagano Prefecture was hit by a typhoon, resulting in a loss of several million yen, and SOLSTICE MUSIC FESTIVAL had to stop holding outdoor festivals due to frequent bad weather.

A few of examples of the most impressive parties were ones organized by “anoyo.” The party called “Rolling Thunder” was hit by a storm, just as the title implied, and the party callled “Ground Swell” held on Niijima Island was hit by an earthquake (laugh). “METAMORPHOSE” was also given the finishing blow by bad weather. When you organize a party in Japan, you are often forced to bear the financial risk of the weather. That was the fate of Japanese parties. Japan is not a very suitable climate for outdoor parties.

Another reason for the decline is that the “peaceful Japanese party scene” that had impressed the foreign DJs mentioned above began to deteriorate around the year 2000. Thieving around the tent sites and sexual assault incidents started happening. The chain-reaction of scum attracting more scum peaked in the mid-2000s. I feel like these two things were the main reasons for the decline.

VISION QUEST” (2000) at Kodama Forest, Nagano, Japan

Photography Kotaro Manabe

From the past to the present, outdoor raves never end

——In recent years, more and more parties are being held outdoors again, how do you feel about this trend?

Kotaro:I think the number of outdoor parties has increased, partly due to the pandemic. The mindset of the people who are holding these parties is also changing. For example, instead of getting sponsors on board and trying to sell 10,000 tickets, many parties are now grassroots gatherings where the people involved enjoy themselves first. This is a very good trend. The size of parties is usually around 100 to 300 people. My impression is that youngsters tend to be “well-behaves” these days, both in a good way and a bad way. They play smart and are more mature than we were. I sometimes think that since they are still young, they should be able to let themselves get carried away, but that’s okay because that’s what they are. When I think back now on what we used to do, I am aware that we were doing something reckless (laughs).

Kotaro with Juno Reactor and other live members right after their live in “EQUINOX” at Doai Campsite, Gifu, Japan (1996)

——You organized your own photos during the pandemic and uploaded them on social networking sites, but what did you think when you looked at them for the first time in a while?

Kotaro:When I look at the quality of the photos, I find myself thinking, “I shouldn’t show them to people” (laughs). I suppose it is difficult to compare the quality of the photos to today. But if you take into account the fact that the photos were taken with the equipment of the time, a part of me think that they have a good texture.

I also wonder how these photos look to people now. Of course, people who knew the parties back then may miss them, but nowadays, people of the same generation as my own children are going to parties. For them, it might be something like us looking at a photo album of Woodstock, so I wonder if it is necessary from a historical perspective to show these photos to the young people of today. I am sure that I am the only person who has such an archive of the parties of that time.

Looking back with Kotaro Manabe on the dawn of outdoor parties in Japan

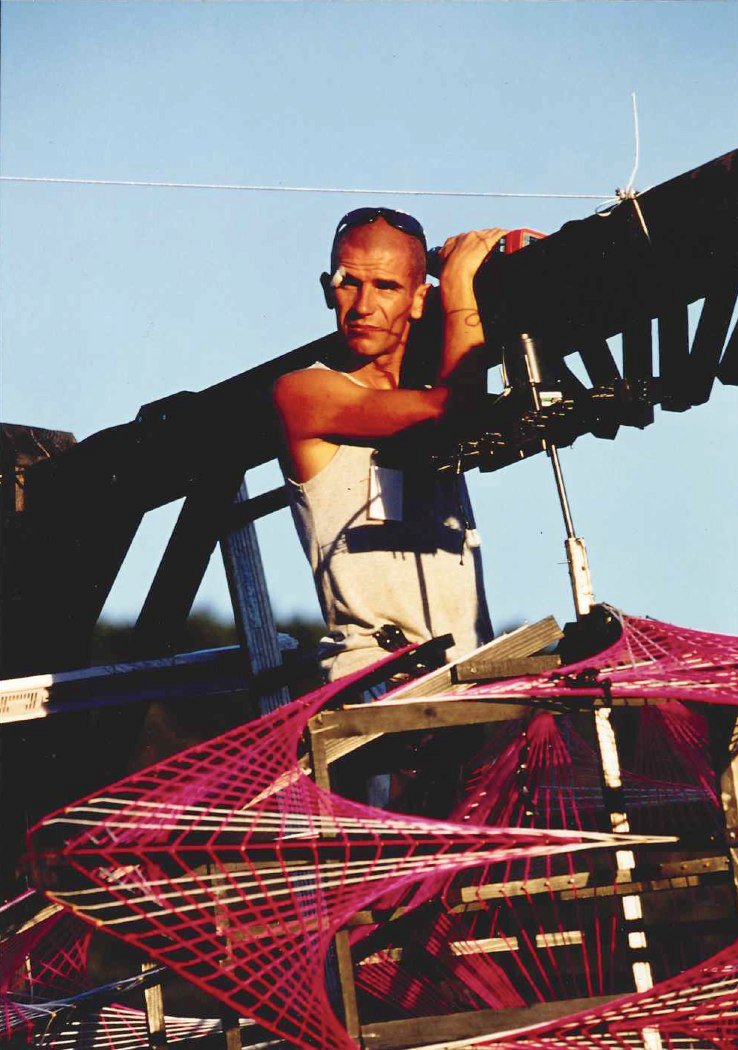

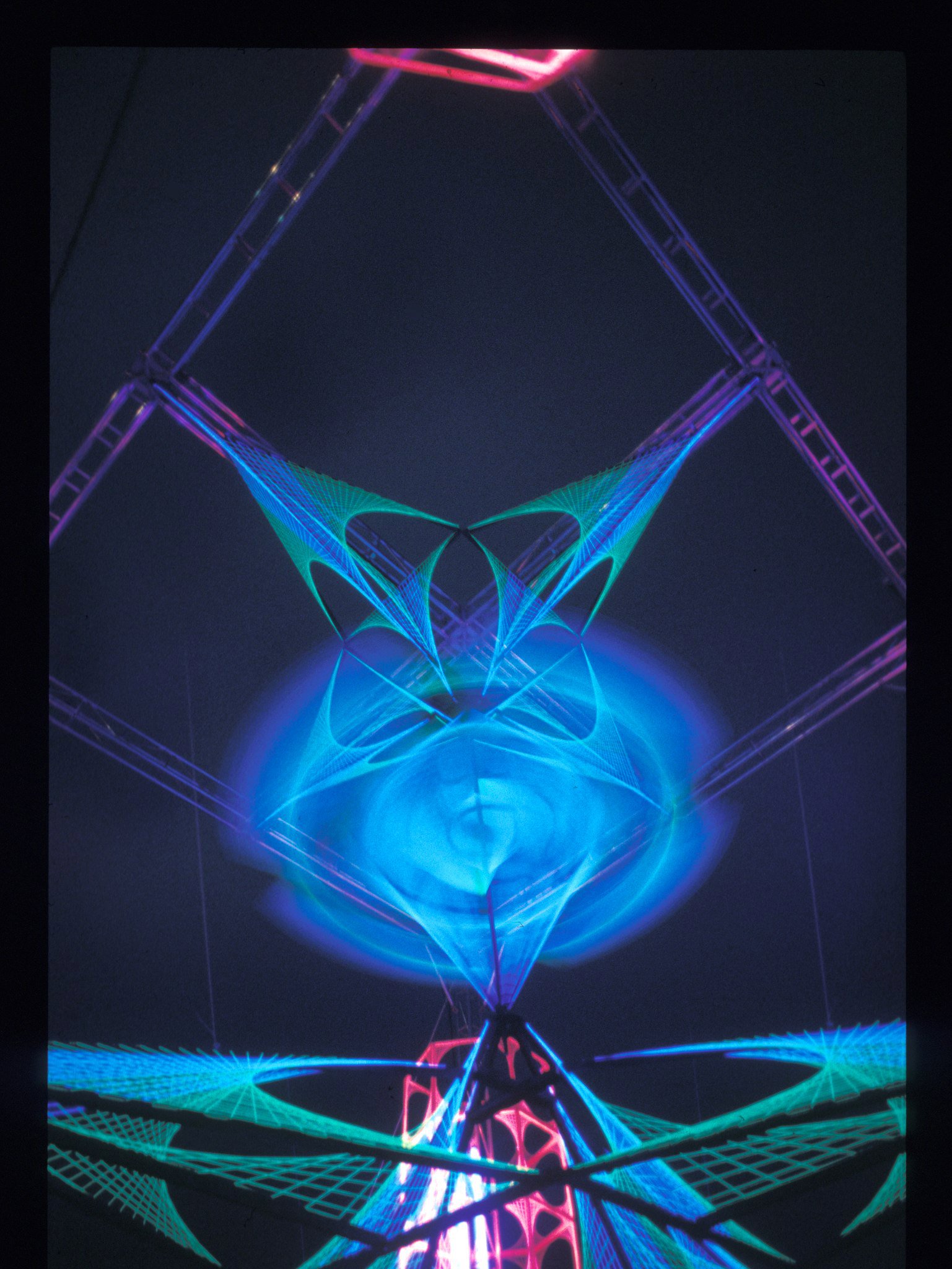

The Strong Sun Autumnal Equinox Festival “EQUINOX” (1999) at Goko Pasture Auto Camp, Nagano, Japan with AVIKAL and string decorations

“I remember Avikal, an Italian, bought some yarn from Okadaya, a handicraft store in Shinjuku, and made a fluorescent colored string. He spun that string around with a motor he bought in Akihabara. At the EQUINOX party at Goko Pasture Auto Camp, we would stay over about a month before the party to make the decorations.”(Kotaro)

Photography Kotaro Manabe

“EQUINOX”(1996) at Doai Campsite, Gifu Prefecture

The photos taken by Kotaro in “EQUINOX” at Doai Campsite were used for the first time on the cover of a publication, the free newspaper BALANCE. Published from 1999 to 2001, the magazine focused on outdoor party culture. It was edited by Takashi Kikuchi, a freelance writer who was also at the center of the scene at the time

Photography Kotaro Manabe

“SOLSTICE MUSIC FESTIVAL” (2001) at Motosu Highland, Yamanashi Prefecture

“SOLSTICE MUSIC MUSIC” was held at Motosu Highland in 2001. The person I want you to pay attention to is Masaru Morita, who led a VJ team called M.M. Delight. He passed away in 2008, but he was one of the leading figures of outdoor parties in Japan and later established the Nagisa Music Festival and other notable events. Morita-san projected the moving images on round balls floating on the lake.” (Kotaro)

Photography Kotaro Manabe

“Hokata Mountain Festival” (2001) at Hotaka Ranch Campground, Gunma Prefecture

“This is Juno Reactor’s show at the 2001 “Hokata Mountain Festival” held at the Hotaka Ranch Campground. About 5,000 people gathered at that time” (Kotaro)

Photography Kotaro Manabe

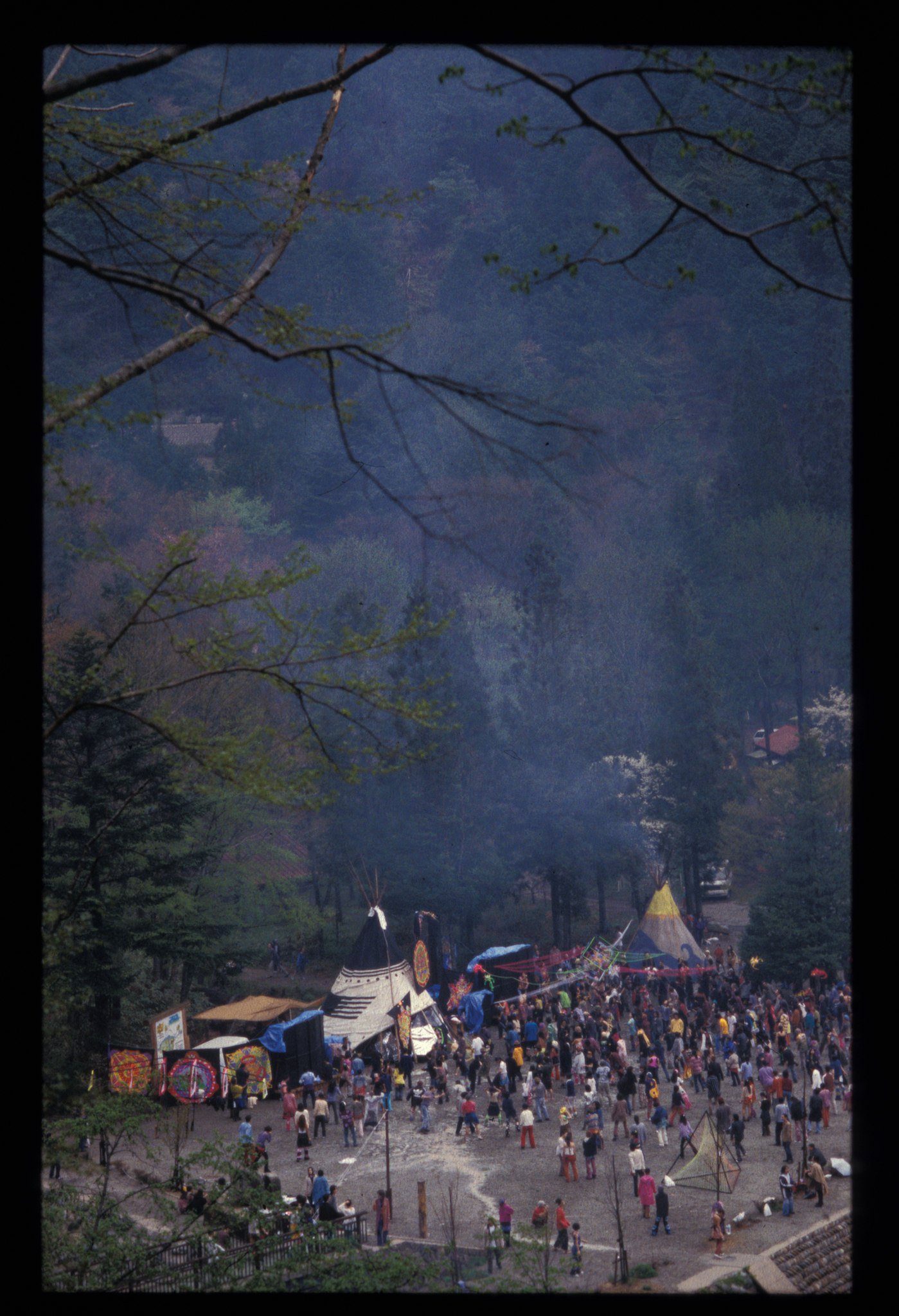

“Harukaze” (2002) at Yoyogi Park, Tokyo

“This is a photo of the party Harukaze at its peak. It was a free party held in Yoyogi Park and everyone could come and go as they pleased. We had to cancel ‘Harukaze’ for the next few years because people who were there not for the party misbehaved in the park.” (Kotaro)

Photography Kotaro Manabe

Photography Taichi Nagai

Translation Shinichiro Sato(TOKION).