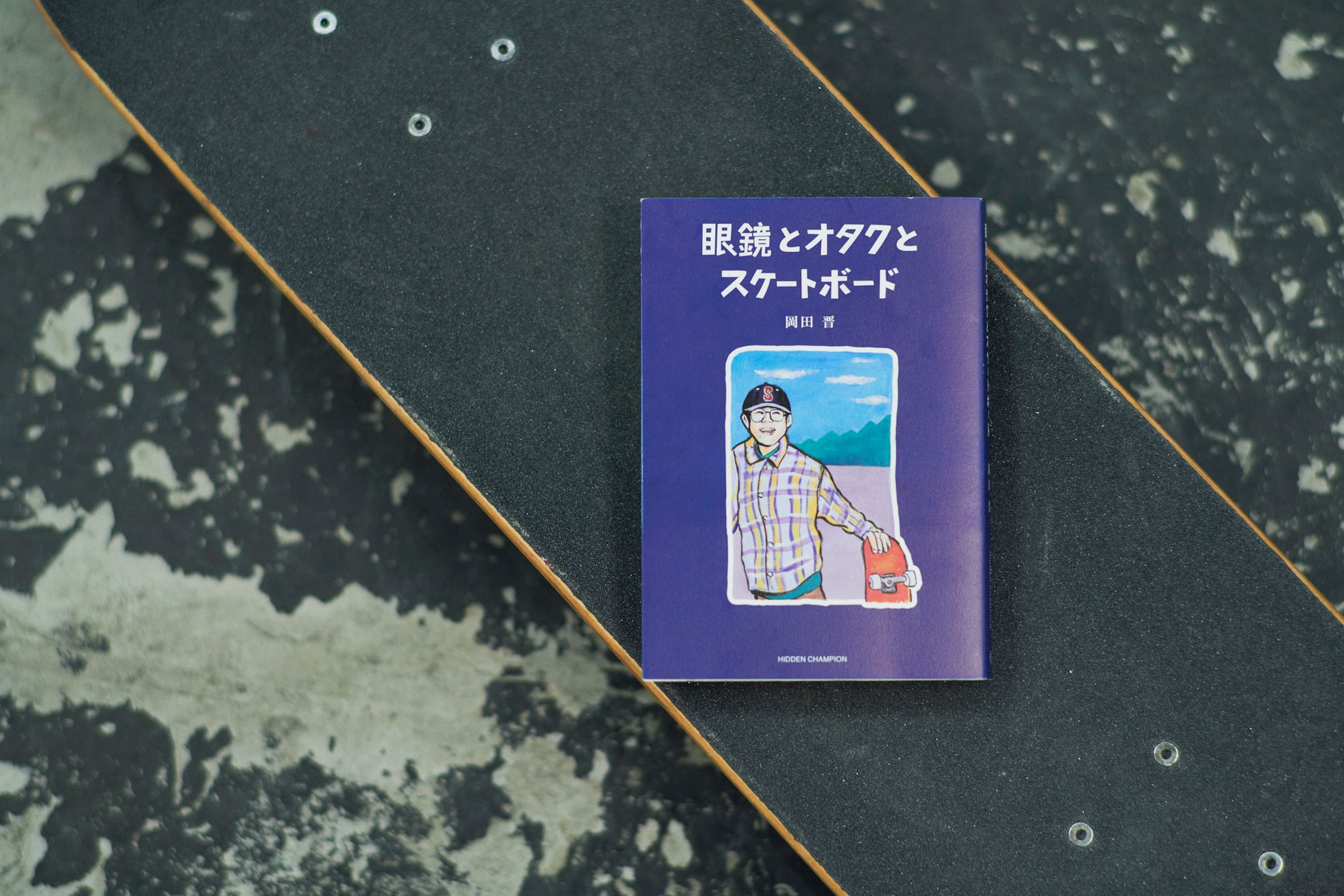

Shin Okada was the first Japanese person to make an international debut with an American skate company, and since then, he has made outstanding contributions to the Japanese skate scene. Okada recently came out with an autobiography, Megane to Otaku to Skateboard. In it, he illustrates his colorful years leading up to his entering the world stage, such as his first encounter with skateboarding as an insecure young boy, joining the legendary skate team, New Type, and being featured in a skate video by American skate brand Prime.

We sat down to speak with Okada in time for the publication of his book and looked back on his early skateboarding days.

Shin Okada

Shin Okada was born in Tokyo in 1977. He started skateboarding seriously in 8th grade and made his international debut in 1994 as the first Japanese person sponsored by an American skate company. Since then, he’s starred in more than ten international skate videos and has contributed to the formation and evolution of the Japanese skate scene. Okada is currently the team producer of the Asics Skateboarding team and continues to contribute to the spread of skateboarding.

Instagram:@shinokada77

“Skateboarding was all I had. I couldn’t get into the things my peers liked.”

――How did Megane to Otaku to Skateboard come about?

Shin Okada(Okada): This book was on the back burner for a decade. I had a blog on my website ten or so years ago, intending to turn it into a book. But I couldn’t make it happen. I spoke to different people about it, but nothing came out of it. Ten years passed, and I casually brought it up to Matsu-san (Hidenori Matsuoka, chief editor of Hidden Champion), and we decided to publish my book. He treated it like we were going to Disney Land the following week. That’s how quick it was. You never know what will happen in life. Perhaps the time to put this book out was supposed to be now, not a decade ago.

――The book goes through your teenage years when you started skateboarding. How did you first discover it?

Okada: It was trendy. In elementary school, rollerskating was popular because of Hikari Genji, and then SMAP came out under the name The Skate Boys. Toy stores started selling skateboards alongside roller skates. The first time I came across one was when my friend brought it while hanging out. I was in 5th grade. It had a Tony Hawk-ish logo on it, and it was one of the mass-produced boards, not the type you would buy at a pro skate shop.

――When did you start skating seriously?

Okada: It was the beginning of 8th grade. I met Naotaka Ohya (Nao), a skater a year younger than me, and got into authentic skateboarding culture. Nao moved to my middle school, and there was a rumor that he could jump on his skateboard. I approached him and asked him where I could get a real skateboard. He showed me skate videos and took me to skate shops. From then on, my life was a cycle of going to school, skating, coming home, then sleeping. I would get sleepy after dinner because I would skate so much. I used to be asleep by 8:30 PM. My family would laugh at me, saying, “You’re going to bed already?” I would come home from school, change clothes within five minutes, and skate until the sun went down. I would skate from the morning to my curfew on the weekends. That was my life.

――You never felt like skipping it?

Okada: No. Not even a single day. Skateboarding was all I had. I couldn’t get into the things my peers liked. Everyone would talk about girls and a show or a music program they saw the day before, but they weren’t interesting. I was frustrated because I wasn’t stimulated enough. I tried many things because I had to find something stimulating at school. But that got me nowhere, and people started treating me with caution.

――You write about your insecurities with human relationships in your book. How you discovered skateboarding and spread your wings reminded me of one of the protagonists of Shonen Jump.

Okada: That’s because I was the archetypal loser (laughs). I became passionate because I discovered skateboarding, but I would’ve turned out so different had I not discovered it. But I don’t think I could’ve blended in at school either way.

I got into skating because my life outside of school became bigger. The more I went skating, the more I saw people who were good at it. I started seeing different worlds. I believed the people in the American skate videos I would watch at skate shops would go pro one day because they were out there in the real world. So many things happened in the real world, and most of the people I hung out with were older. That was fun for me. Every day was like a role-playing game. I was more determined to skate than playing Dragon Quest.

――It’s amazing how you made your dreams into reality instead of just thinking about them in your head.

Okada: I had the strong ability to believe. I was like, “I can make it happen; there must be an opportunity; I can get there.” It was like I found a map leading to jewels in the backyard and truly believed in it. Until then, I felt so frustrated; nothing fulfilled me. But skating was the only thing I enjoyed. It was the one. Skating was deep, like a swamp, and I could and wanted to skate forever. I just skated all the time. It was the right kind of stimulation.

――You also write about feeling insecure about your glasses when you started skating.

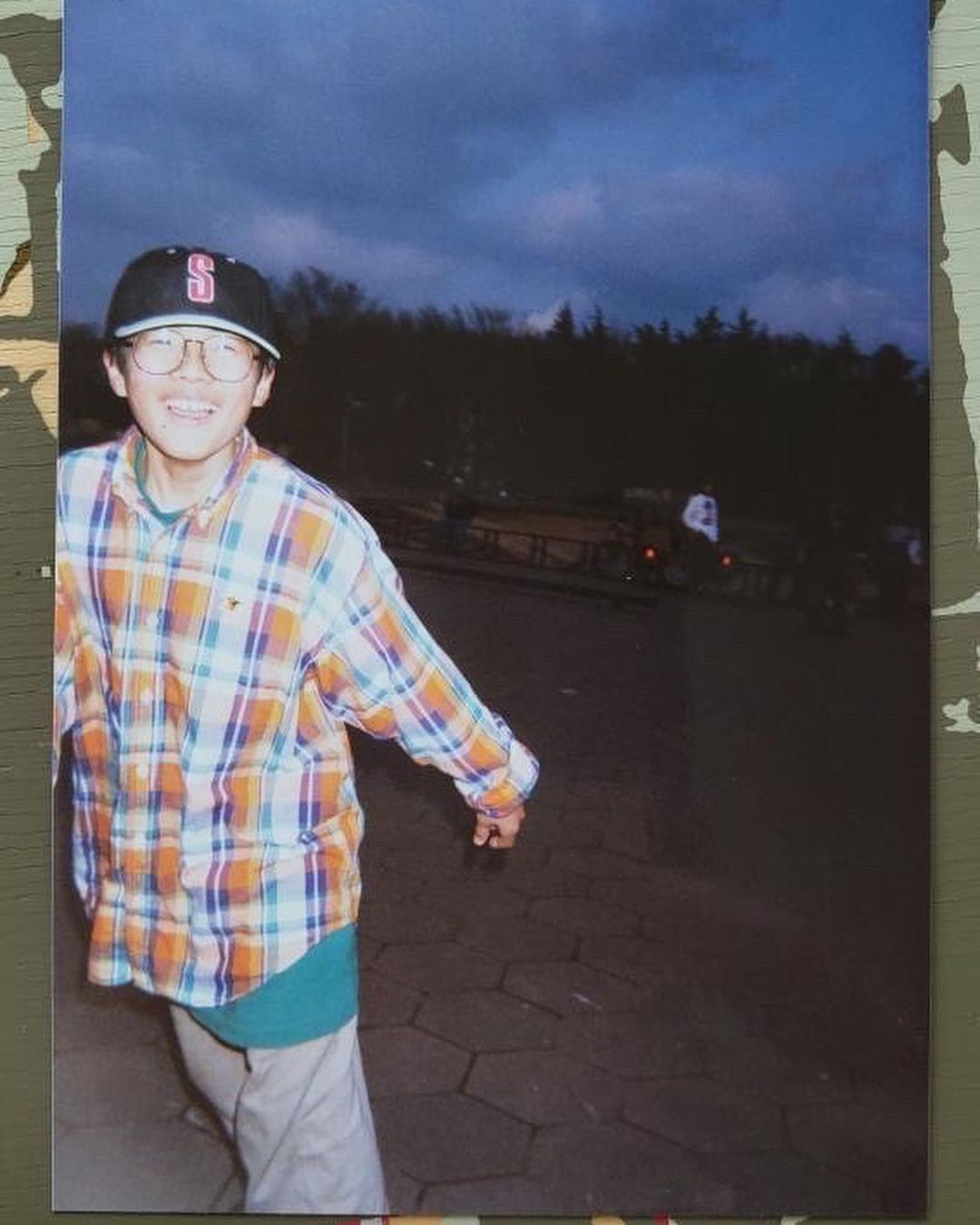

Okada: Only a handful of people skated and wore glasses. Toru-kun (skater Toru Yoshida) looked so cool with glasses on, but no one wore them to be stylish. People associated glasses with Nobita-kun from Doraemon, a marker of hillbillies. I looked so awkward, like this (points to an illustration from the book). Only edgy kids skated back then, so people used to be like, “Who’s this guy? Hey, look at this weirdo.”

The cover of Megane to Otaku to Skateboard was based on this photo of Okada as a boy

Driven people who go for what they want will make it in the world

――You’ve been in the skate scene since the era you’ve written about in your book, which was long ago. Do you often feel a difference between the past and now?

Okada: It’s a hard one. I feel like it’s evolved a lot, as someone who’s witnessed the scene change, and I also think it’s stepped up a level because of the Olympics. But as someone in the scene, I don’t think the vitality, motivation, and way of thinking of pro skaters have changed.

No matter how social media advances or how people pay attention to skating because of the Olympics, the core thing skaters require to improve hasn’t changed.

――By “core thing,” do you mean the desire to be better and win competitions?

Okada: Yes. Another is making videos. When emotion, action, and tenacity become one, and you don’t overthink things and go for what you want with your gut instinct, you can make it big in the world. You have to do everything and be like, “Let’s make a wild video. Let’s show it to someone. Let’s enter a competition and win it.” Those who are proactive and believe something is waiting for them, like Luffy from One Piece, will make it big in the world, even left to their own devices.

――You’re currently the team producer of the Asics Skateboarding team. Do you often feel that drive from the young skaters?

Okada: It’s rare to see a kid like that nowadays. It seems like not a lot of them have that feeling. But it’s just that they don’t know. I’m sure they’ll improve if there’s someone on their case, just like I was taught things when I was a kid.

When writing my book, I realized I am where I am today because of the talented people who lectured a cheeky brat like me. I want to convey that at Asics Skateboarding. If there’s an experienced adult, the skaters will listen to what they’ve got to say. I have nothing to complain about their potential and skill set, so I want to teach them about motivation and aiming for something greater. I want to tell them, “Let’s strive for something bigger. It’s not embarrassing to do it. You’ve got to integrate skating into your life more.”

――Have you ever thought about what kind of skater you’d want to be if you were a teenage skater in today’s world?

Okada: No. Skating wasn’t an Olympic sport back then, but I’ve experienced almost everything I could imagine. It makes me tired just thinking about doing it again (laughs). I also don’t look at the young kids and think, “I would do it like this if I were them.” I genuinely think they’re great.

――What about the future? What do you want to do as someone in the scene?

Okada: Nothing (laughs)! I don’t want anything to do anything half-baked and related to skating. I’ve experienced enough as someone in the scene. Of course, I have Asics Skateboarding and might be involved in skateboarding content, like my book. “Content” might make it sound like I’m not taking this seriously. Nonetheless, I want to keep a close eye on the scene, but I don’t want to be aggressive about it. I also don’t feel the need to be assigned a role or cling to one.

――What are your thoughts on the skate scene in the near future?

Okada: It’s too arrogant of me to say what I want the skateboarding world to be like. Everyone plays a part in building the scene, and it’s not about what anybody says. The mindset of a skater is to transcend the box skaters are put in.

Those who create things beyond people’s idea of skating will expand and deepen the scene. They motivate me. That’s why I want to watch the scene closely.

――What’s a significant aspect of skating that you’ve come to realize in your 30 years as a skater?

Okada: (Thinks for a while) I’m not sure, especially not now. There’s no distance between the scene and me. I wonder (laughs).

――It’s an integral part of your life, so it’s hard to step back and see the bigger picture.

Okada: It’s more than that. I can’t find the answer, nor am I looking for one. It’s as though skating has melted in my body and dissolved. It’s like my blood sugar (laughs).

――(Laughs). Thank you. Those who don’t know much about skating could feel encouraged and empowered by your book. Lastly, could you give a message to prospective readers?

Okada: Let the youth dream. Let there be hope for the next generation. Let there be love for the 90s!

Photography Masashi Ura

Text Kango Shimoda

Translation Lena Grace Suda