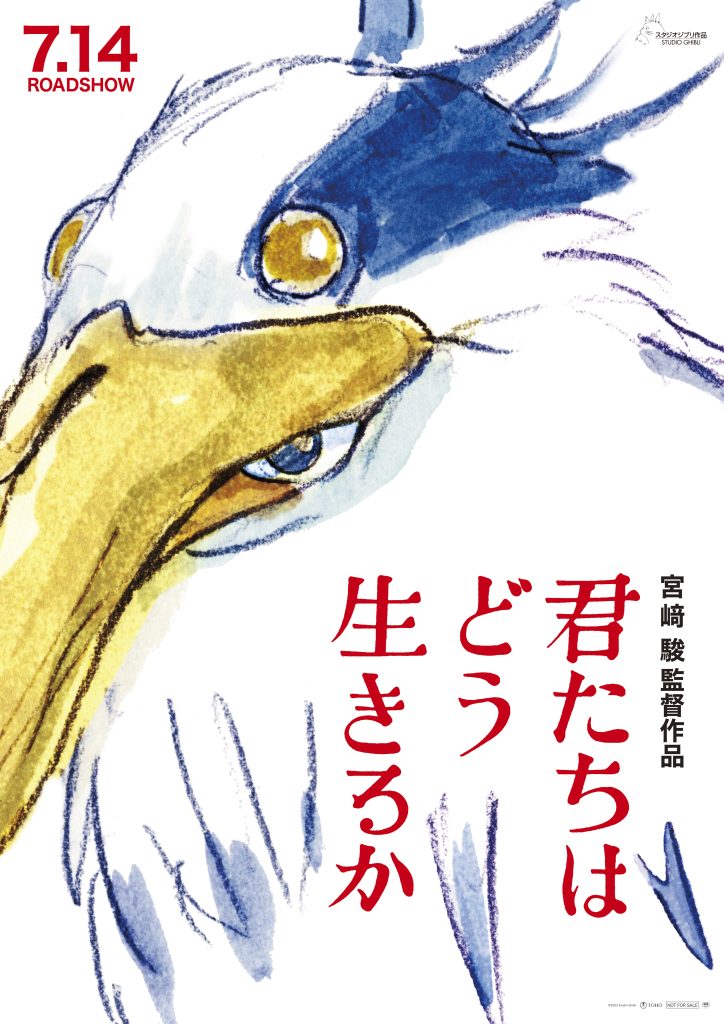

On July 14, Studio Ghibli released animator and filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki’s first movie in 10 years, The Boy and the Heron. The movie attracted even more attention for its no-advertisement policy. It has gotten off to a strong start, drawing an audience of 2.32 millions and earning over 3.6 billion yen at the box office in the first ten days. On the other hand, the movie has been the subject of diverse interpretations, with various articles on the Internet discussing a variety of topics in it. We at TOKION asked up-and-coming cultural critic Shun Fushimi to write a column on this animation work.

※Please be aware that the following text contains spoilers.

Commentaries Increase

The Boy and the Heron is an animation consisting of “increases” and “collapses.”

As soon as this Japanese master animater’s long-awaited work was released, many authors commented on it. It is common for such a high-profile movie to have a lot of words on it circulated on the Internet after its release. However, particularly with this work, there has been a flood of texts, which is becoming even more extensive. Much of the discussion focused either on the “mother” in the story or on the idea of “inheritance,” applying the relationships around Studio Ghibli and the history of Japanese animation to the characters and story in the film. In the former case, Tsunehiro Uno, for example, describes the film as “a self-commentary of Miyazaki himself on what is at the core of him, which is typical post-World-War-II-version of mama’s boy mentality, as if it were written by a critic” (*1), and Kaho Miyake writes that “a world where father is absent, mother and her child are in close contact, eggs cannot be born, and the voices of screaming parakeets echo virtually” is a “nauseatingly accurate metaphor” for our times (*2). For the latter, hiko1985, author of the blog “青春ゾンビ (Youth Zombie),” points out that the character “Kiriko” is a metaphor for Isao Takahata and Michiyo Yasuda, Miyazaki’s sworn allies from days in Toei Animation (*3), and Seiji Kano sees in this movie a “return to a manga movie” that inherits the “legacy of those who have worked closely with Miyazaki, such as Isao Takahata and Yasuo Otsuka” (*4). Perhaps it is a blessing in itself to be able to extract multiple narratives from a piece of work because it is a testament to the fact that Miyazaki and the rest of the Studio Ghibli staff have been making movies for decades and that so many viewers have been receiving them for so long. However, the storyline plays only a secondary role in feature-length animation. The primary stimulus to the audience’s senses, and what the filmmakers pursue above all else, is the movement within the sequence of pictures. Without this, the story around the mother and the references to the real persons are nothing more than easy manipulation of symbols, and brings no excitement.

(*1) Tsunehiro Uno. ” The Boy and the Heron and the Problem with the ‘King’”.2023-07-20.

https://note.com/wakusei2nduno/n/nc1c94c0793fe, (referred to on 2023-07-27)

(*2) Kaho Miyake.” #What was Hayao Miyazaki ultimately trying to portray in The Boy and the Heron [Fastest review with spoilers]”2023-07-15.

https://note.com/nyake/n/nc74f29fccca2, (referred to on 2023-07-27)

(*3) hiko1985. “Hayao Miyazaki, The Boy and the Heron, ” 青春ゾンビポップカルチャーととんかつ. 2023-07-17.

https://hiko1985.hatenablog.com/entry/2023/07/17/135024. (referred to on 2023-07-27)

(*4) Seiji Kano, “The Boy and the Heron: A Return to ‘Manga Movie’ with Adjusted Logic.”. Cinema Cafe.2023-07-21.https://www.cinemacafe.net/article/2023/07/21/86462.html, (referred to on 2023-07-27)

“Increase” Overflows

In the middle of the movie, the jam increases. In this scene, Himi, one of the heroines of the movie and an incarnation of the protagonist Mahito’s mother in the other world, serves Mahito a piece of toasted bread with jam in a Western-style kitchen. Himi spreads a thick layer of butter on the toast, puts red jam on top, and gives it to Mahito. Mahito takes a bite of the toast. The jam spills out, ending up being around his mouth. “It’s tasty. My mother used to make it for me,” he says to himself. He bites into the toast again. Then, that red jam overflows from the toast and spreads out in front of his face, which is drawn in a medium close-up shot. The amount of jam clearly exceeds the amount that Himi had applied to the toast in the first place. The jam increases. It overflows. It proliferates.

The way the jam increases and the color of red remind us of a scene in which Mahito bleeds, placed in the first half of the movie. On the way back home from school to which he has just transferred. After a fight with classmates, Mahito suddenly strikes his right temple by himself with a stone he picked up. Against the blue sky and the green forest, a dark red stream flows out from his temple. The blood doesn’t stop right away. Instead, it gushes out in the next cut. If it really happened to a flesh-and-blood human being, the amount of blood would be enough to cause death in some cases. It even looks as if the blood itself is growing. The blood increases. It overflows. It proliferates.

The movement of ” increase ” links the jam and red blood. What at first glance does not appear to be a significant quantity overflows and spreads in the next cut. The movie is overfilled with this kind of proliferation and movement of increase.

For example, in the scene where Mahito and the blue heron confront each other for the first time at the pond behind the mansion and exchange words. When the heron belligerently says, “I’ve been waiting for you, sir,” catfish-like fishes appear from the pond, and in the next cut, a large number of frogs appear, crawl up from under Mahito’s feet, and surround his body. The catfishes and frogs suddenly multiply.

Or the scene in which Mahito is guided by a blue heron into another world. A golden gate stands in a windy field. As Mahito gazes up at the gate, a flock of pelicans suddenly swarms over him. The weight of the pelicans pushes the gate open. The gate’s opening leads to Mahito’s encounter with the sailor Kiriko (one of the elderly ladies in the real world), and here, too, the sense of proliferation is depicted through the flood of pelicans.

In the two scenes I just mentioned, a large herd of animals appears, but the sense of proliferation is not brought about only by the animals. In both scenes, the wind is blowing before the herd appears. The strong wind causes Mahito’s grayish shirt to flap and sway. At this time, the shirt’s contours bulge out in an unnaturally rounded form. After Kiriko and Mahito meet, the sea begins to swell. As the two proceed in their wooden boat, a huge wave appears before them, covering the horizon. The wave rises high and covers the boat, which is shown from the left side. Both wind and water are depicted in this movie as part of the phenomenon of increase and overflow.

In this light, it seems that the group of elderly women working at the mansion in the real world also has something to do with the “increase” movement. The appearance of the old women who gather like ants around the luggage that Mahito’s father brings back to the mansion is accompanied by an unusual sense of proliferation from the start, and their wriggling in groups of five or six is reminiscent of the elderly ladies in the nursing home in Ponyo (what both groups share are one woman with a wart on the side of her nose and another who acts independently from the group). However, the reason why the group in The Boy and the Heron leaves us with a creepy impression becomes apparent when these women are depicted from the side. Their eyes are weirdly popping out of their heads. Their eyeballs are so enlarged that they look as if they are about to spill out. The combination of the large roundness of their eyes and their collective wriggling and chattering forms the impression of an eerie proliferation.

In addition, the “Warawara,” a group of white creatures that live with Kiriko and are said to be the form of pre-human, are also part of the “increase” movement, as are the swarm of parakeets that develop a hostile relationship with Mahito, Blue Heron, and Himi in the latter half of the movie. In this work, the movement of “increase and overflow” abound all the way through the story.

This “increase” movement has appeared frequently in Hayao Miyazaki’s previous movies, as exemplified by the seeds planted by Satsuki and Mei being rapidly transformed into a large tree by Totoro’s mysterious power in My Neighbor Totoro, the swarm of Ohmus in Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, the swarm of fish and the proliferation of the anthropomorphic sea in Ponyo. In the early part of it, Mahito’s father, Shoichi, and his company’s employees line up the windshields of the fighter jets’ cockpits they are building at their company one after another at their mansion, and this “increase” movement links to the way the windshields of the swarm of flying Zero fighters were highlighted at the end of The Wind Rises (Even from the perspective of the period setting, the movie, The Wind Rises is followed by The Boy and the Heron) Therefore, this work can be said to be the newest version of the “increase” movie directed by Hayao Miyazaki.

“Increase” is Accompanied by “Collapse.”

The “collapse” movement reveals itself accompanying the depiction of “increase.” In the middle of the movie, Mahito, while being taught by Kiriko how to do it, cuts a huge fish (looks like an anglerfish) that Kiriko has caught. Following her instructions, he plunges the blade into the belly of the giant fish, and blood gushes out. Once again, Mahito thrusts the blade. Immediately afterward, the fish’s pinkish viscera begin to overflow and spill out of its belly. On the screen, the viscera are increasing in volume toward the outside of the belly, but the fish’s body is collapsing. An increase is sometimes accompanied by collapse. Another “collapse” awaits after this scene. According to Kiriko, the guts of the fish are the fodder for the Warawara to float. She explains that at night, the Warawaras rise into the air and the group of them gradually form double spirals, reminiscent of a double-helix structure of DNA, eventually reaching the “upper world,” where Mahito came from, to be born as human beings. Pelicans, which feed on the rising Warawaras, appear and try to devour them, but Himi, the fire girl, appears and releases a firework-shaped flame to save them from the pelicans. That night, Mahito meets a dying pelican beside an outdoor toilet. The pelican falls to the ground and collapses, complaining about the dire situation of the pelicans, who have nothing to eat but Warawaras. Again, we can see the contrast between the movement of the pelican, who collapses in solitude while the flock of Warawaras rises into the air.

As with the case of “increase,” “collapse” is another key movement that has underpinned Hayao Miyazaki’s animations. In Laputa: Castle in the Sky, Princess Mononoke, as well as Spirited Away, the collapse of a world occurs in the final stages. Both the Giant God Soldier and Shishigami crumble as if they were melting. In The Boy and the Heron as well, the world created by the “great-uncle” with a contract with “stones” finally collapses with a heavy thud. This movie can also be said to be the newest version of the “collapse” movie.

If “collapse” is one of the common gravities in the world of Hayao Miyazaki’s animations, then we could accept some of the puzzling scenes in this work with no hesitation. In one scene, a heron invites Mahito to a stone tower. Inside the tower lies Mahito’s mother, who is supposed to be dead, but when Mano touches her, her figure dissolves into the water. This scene does not foreshadow anything that happens in the later part of the story, leaving the audience with a puzzling impression. However, if we are to believe the collapse of the mother’s figure is a movement depicted in accordance with the gravitational force of “collapse,” there is no room for doubt about the scene’s necessity. How about the scene just before the great parrot king meets Mathito’s great-uncle on the tower? The King climbs up the wooden staircase, and when he reaches the top step, he carefully destroys the stairs. This must have been done to prevent his pursuers, Mahito and the blue heron, from reaching the top. But looking at him smashing them four times, one would think he is overdoing it. In addition, it turns out that his attempt was ineffective because the two pursuers eventually met his great-uncle through a different route. So here again, the movements in the animated pictures do not ensure the story’s coherence but can be said to rest on the gravity of the “collapsing” movement.

Movements Precede Metaphors

Meanwhile, it should be added here that there have been criticisms about “movements” in this work. In an article by Kazeto Shimonishi, which deserves attention for pointing out the fact that the opening scene is a “subjective image” of Mahito and that the entire depiction of the work is “exaggeratedly grotesque,” he points to the technical limitations of the work, stating that “the expression of ‘movements’ is far inferior to what it was in Miayazaki’s prime,” and that “perhaps due to physical decline, Hayao Miyazaki is no longer able to draw.” (*5) It is true that this movie does not have the dynamism of, for example, Porco Rosso. The swarm of ships and the plants in the garden of Himi’s house, both in another world, seem less elaborate and vivid than the swarm of airplanes Porco saw in his visionary experience and the beautiful garden of Gina’s house. The light shining through the clouds also lacks the variation of shading expressions compared to those in Porco Rosso, of which I couldn’t help but feel the monotonousness and uniformity. We cannot find meticulous depictions of forests seen in My Neighbor Totoro or crowds in The Wind Rises, let alone the appeal of the flexible pencil lines in Ponyo. While I would refrain from simplistically attributing these differences to Miyazaki’s “old age” or “decline,” it would be unreasonable

not to acknowledge the differences themselves. (*6)

(*5) Kazeto Shimonishi, “Hayao Miyazaki’s Sorrow and Question — The Boy and the Heron“. 2023-07-21. https://note.com/kazeto/n/nca1be7cd479c, (referred to on 2023-07-27)

(*6) In an interview by Yoichi Shibuya for “Sequel: Where the Wind Returns,” Miyazaki frequently bemoans the lack of skill among young animators. If we are to believe him, the reason for the reduced sense of dynamism in his newest movie should be attributed less to the director’s age and more to the lack of skill of the animators in an age when working with a PC has become the norm. Of course, a writer who has never worked in animation does not have the ability to pursue the cause or responsibility. See Hayao Miyazaki (2013), Sequel: Where the Wind Returns: How the Filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki Began and Ended His Career, Rocking On.

However, this movie surpasses all of Hayao Miyazaki’s previous works in its relentless repetition of the same movements. The proliferation of the trees in My Neighbor Totoro is only seen in a single scene. In Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, the increase of Ohmus and the Sea of Corruption is not exempt from narrative inevitability. In both Princess Mononoke and Laputa: Castle in the Sky, “collapse” is an integral part of the story. Ponyo is an exception in that the seawater, fish, and Ponyo’s limbs “increase” in an uncontrolled manner, but the city hit by the tsunami does not “collapse.” No other movie has been as repetitive as this newest one in that increases and collapses occur everywhere repeatedly, including in scenes not directly related to the storyline. What arises from this repetition is a sense of rhythm that only this work is allowed to live with.

What we receive far more directly from this work than from its story is a series of movements that fall into two categories: “increase” and “collapse”. It is not the construction of a story that the animators devote themselves to, but the generation of movements. We feel “creepy,” “scary,” “nerve-fraying,” or “thrilling” when we sense the increase or collapse of things or creatures. Such sensory reactions precede the idea of tracing the story with the structure of Japanese society and applying the relationships in the work to those of real people.

Therefore, there is an inevitability in the scene in the final part of the work where the characters escape from the other world of “stones.” When Mahito, his stepmother Natsuko, and the old woman Kiriko return to their original world, pelicans and parakeets pour forth from the tower. Behind them, the stone tower collapses completely. This work can be completed by the simultaneous occurrence of “increase” and “collapse” all at once. Mahito and Natsuko, smiling and covered in birds’ droppings, resemble us, the audience, who were exposed to “increase” and “collapse” simultaneously.

It is easy to consider “increase” and “collapse” as metaphors for “life” and “death,” respectively. It would not be wrong to think so. However, we must not get the order wrong. The beauty of this work does not lie in the fact that it depicts “life” and “death” symbolically through the representations of “increase” and “collapse,” but in the fact that the symbols of “life” and “death” can be felt in front of our eyes as wriggling of movements. Without “increase” and “collapse,” the metaphors of “life” and “death” would be nothing more than a mundane theory of life.

Increase, Collapse, and Closure

Now that we have reached this point, it would finally make sense to think about “mother” and “inheritance.” The world that the great-uncle has protected and tried to entrust to Mahito is not inherited, but collapses. Instead, the number of people who have a relationship with Mahito increases. Not only does Mahito call his birth mother “mother,” but he also starts to call his stepmother Natsuko “mother” in the middle of the story. This is not a choice between mothers, but rather an increase in the number of mothers. The conflict between mother and son is overcome through the “increase”. In a cut before the final one, Mathito’s father, Shoichi, and Natsuko wait for him at the entrance with their new child. This cut is depicted from the same perspective as when Mahito once peeked into his father and stepmother sharing an embrace. This repetition reinforces the impression of the “increase” in the number of children. Both “mother” and “child” are increasing in this movie.

But it is not only “mother and child” that increase. In a conversation with his great-uncle, Mahito describes the scar on his temple as “a proof of my malice.” Kiriko, a sailor, had a scar in the same spot. “Malice” is also amplified. At the same time, in his conversation with his great-uncle, Mahito said that Himi, Kiriko, and blue heron were “friends.” And when they parted, the heron bluntly said to Mahito, “Bye, my boy.” In the first place, the blue heron has an “increased” face: a face of middle-aged man emerges from beneath his face as a bird. It is mentioned several times in the dialogue that he is a “liar” with two faces, but the “liar” blue heron and Mahito become “friends” in the end. Furthermore, since Himi is an incarnation of his dead mother, Mahito also becomes friends with “death.” That is to say, Mahito is saying that “malice,” “lies,” as well as “death” are his friends. “Friends” are portrayed as something that will only increase.

A kingdom that has been protected for many years collapses without being passed on. Mothers, children, malice, lies, and friends increase. We never know what is truly in the minds of the creators of this work. Even if we did know it, it is not necessarily reflected in their work. However, the sequence of pictures and sounds in the movie titled The Boy and the Heron whispers at our ear as follows: “You and I are creatures who are irresistibly attracted to ‘increase’ and ‘collapse’ rather than ‘protect’ and ‘inherit.’ Everything that ‘increases’ is free from moral judgement, and they all become your ‘friends.'” Whether this is right or wrong is, of course, not mentioned anywhere in this movie. The door closes without telling us anything, even with no words like “The End” or “Fin” to mark its end.