YAMAN NKYMN

YAMAN NKYMN is a maestro strategist and contemporary artist based in Los Angeles and Kyoto, Japan. He studied at Kobe University, Japan, graduating in chemistry in 1999. He began his career as a marketing strategist, working globally for leading fashion houses such as Louis Vuitton, Chanel, and Gucci.

In 2019, he worked on the animation movie “Shin Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time” as the strategic director, establishing the company “YamAnno” with the film director Hideaki Anno for the movie. The film surpassed 10 billion yen in box office revenue, approximately double that of the previous film in the series.

He began his career as a contemporary artist in 2021 with the exhibition “陸奥の 安達原の黒塚に 鬼籠もれりと言うはまことか (UN)KEEPALL” at the Japanese National Treasure, Hiunkaku in Nishi Hongwanji Temple. The following year,

the work was invited to the art fair, Frieze Week Los Angeles and premiered at the Chateau Marmont in West Hollywood, his global debut, just one year after his first exhibition.

Back in 2012 his work evolved, adapting to fast-changing social behaviors into the creation of original content – entertaining, interactive, gamified, using algorithms to observe a communicative world and data collection, accelerating the process.

Following the principles of chemistry, YAMAN’s practice is a recodification characterized by a juxtaposed observation of the laws at play in both matter and society – invisible states, relationships, interactions, conditions before reaction and under equilibrium.

From this dual, coupled perspective, YAMAN notices imbalanced states in society and turns his focus to the source of distorted definition, information transmission which defines the minority or ‘other’.

Artist YAMAN NKYMN, who was invited to be part of the official program of “Frieze Los Angeles 2022” and whose documentary “THE ULTIMATE OTHER” (2022) was produced by Frieze Studio only one year after his debut as a contemporary artist, presented his new artwork in Kyoto.

This newest piece, which was shown in an area not usually open to the public at Hoshunin Temple, Daitokuji, was titled “年ごとに 人はやらへど目に見えぬ 心の鬼はゆく方もなしWHITE2BLACK 11072023”. The invitations we received at our editorial office only stated “(跡見:)追儺 黒節分/(ATOMI:)WHITE2BLACK”. What is the significance of Oni that consistently appears in his work? Why was the poem by a female poet used as a title of it in the first place? We were honored to sit down and talk to YAMAN NKYMN about the creative background of this work and the sources of its inspiration.

The sediment that has accumulated over time brings out the artist’s personality

–How does your expertise and experience as a maestro-strategist influence this specific work or your practices as a contemporary artist?

YAMAN NKYMN (YAMAN): The influences from those are significant. In the first place, working as an artist makes me realize how ordinary I am. Basically, I don’t have anything like an “overflowing creative urge.”

Instead, what I have as an artist is a kind of sediment that has accumulated through my sincere commitment to the roles of marketer and strategist. The conflict between ideals and reality. The distortion between creative and commercial activities. The essential quality being spoiled day by day, by being forced to deal with superficial things.

Personally, I despair that there is a gap between the “ideal state” and the “actual state,” especially in industries like fashion and animation. I feel that because, even if the industry is made up of people who like working in that area, the ideal cannot be realized.

Being involved in those industries as someone in charge of the figures would accumulate a special kind of sediment because of the objective viewpoint one is forced to take. Conversely, the sediment that has accumulated little by little has constructed a message that can be disseminated because I am ordinary.

Therefore, all the elements in my work are simply what I have experienced, researched, and repeatedly thought about.

Only the fact I was forced to “communicate” in the position of the ordinary person’s job in a creative society formed a distinctive characteristic within myself. The sediments I have accumulated over time are not so easily understandable to others. On the other hand, just because it does not make sense to others does not necessarily mean it is incorrect. That is why I explore how I should communicate, contemplating whether to use metaphors or paraphrases. This “Chanoyu” style of expression is one such example.

–Is your career related to your references to subcultural icons and elements?

YAMAN: Some aspects are related, and others are not. In terms of unrelated aspects, I am the type of person who plans projects in a “3+1 dimensional” manner. It’s kind of like meditating on the world (3 dimensions) with a free time axis (+1 dimension). In other words, it is a Kurt Vonnegut-like thinking, or the mode of thinking often seen in science fiction. In other words, I treat these last 100 years “Showa/Heisei/Reiwa” eras as equivalent to the “Heian and Azuchi-Momoyama” eras, 1200-500 years ago. For me, Astro Boy is as valuable as Sen-no-Rikyu. That means I am the kind of person who thinks modern culture is temporally connected to the classics in a seamless manner.

Paradoxically, in terms of related aspects, the more classical, the heavier and slower, and the newer the content is, the lighter and faster. “Messages” are heavy and slow, but entertainment is light and fast. This is a critical perspective for contemporary marketing. It is not a dichotomy, but what matters is a balance, a middle ground between the two. Regardless of whether it is legitimate as an artistic expression, this sense of balance seems to be, at least at this point, a way in which I can continue to face the world without despairing.

In addition, my involvement in social media marketing for more than a decade since 2007 was a direct impetus for choosing “relational art” for this specific work. In other words, communication itself has been at the center of my career, and the key to this has been the balance between online and offline. If you read the literature of several critics since Nicolas Bourriaud’s seminal work published in 1998 from this perspective, you will notice that the relational infrastructure on which these works are based is different from that of today with the existence of, for instance, social media. Therefore, I thought of composing a new work as “relational art in 2023” while incorporating the previous work “陸奥の 安達原の黒塚に 鬼籠もれりと言うはまことか (UN)KEEPALL” which focused on the same concept.

–”年ごとに 人はやらへど目に見えぬ 心の鬼はゆく方もなし WHITE2BLACK 11072023” and ”(跡見:)追儺 黒節分/(ATOMI:)WHITE2BLACK”, what are the meanings of the two names of your works?

YAMAN: The former is the title of my work of contemporary art. It is taken from a waka poem by Kamo-no-Yasunori-no-Musume, a woman of the mid-Heian period (end of C9th to mid C11th). This waka poem by a minority woman poet, who was physically scarred by a plague epidemic and living outside mainstream society, and who left us free, vigorous, and sharp creations, expresses all that this work means.

The latter is a title of Chaji, an authentic Japanese tea ceremony, which was named from the majority viewpoint. To give you an explanation, the name is linked to the date of the event. Today, in Japan, the term Setsubun makes us think of the Setsubun in February, but originally, Setsubun is the day before Risshun, Rikka, Risshu, and Ritto, the starting point of each season. 黒節分/WHITE2BLACK is the term coined to indicate the day before Risshu, the turning point from autumn to winter, referring to the theory of Yin-Yang and the five elements.

In this exhibition, the number “3” and multiples of 3 are spotted everywhere in this work. Since my previous work, I have dealt with the idea of de-dualism as one of the themes, such as “Oni,” which ranges between good and evil. The number “3” indicates “oneness,” the integration of duality. In Buddhism, it is said to represent “moderation.” Having two aspects, my work of contemporary art and Chaji, an authentic Japanese tea ceremony, reveal an infinite number of possibilities through this “oneness”.

–Please give us an overview of the exhibition once again.

YAMAN: “(跡見:)追儺 黒節分/(ATOMI:)WHITE2BLACK” consists of two different events spanning two days as one set, which are “追儺 黒節分/WHITE2BLACK” and “跡見: 追儺 黒節分/ATOMI:WHITE2BLACK”.

On the first day, the former invited three people for a 3-hour tea ceremony. Theaster Gates, Hirohiko Araki, and Raku Kichizaemon XVI were the guests of honor on each day. The relationship between the host and guests begins with welcoming them at Kinmokaku, the main gate of Daitokuji Temple. After that, we moved to Hoshunin Temple to proceed with Chaji, the authentic Japanese tea ceremony, two types of matcha tea and Kaiseki cuisine after the reception experience .

On the second day, the latter was conducted for 27 people per day in the form of “ATOMI(-no-Chaji)” in tea ceremony culture, and the exhibition was organized in a way that the vestiges of the Chaji held on the first day were visible. A sheet of paper, called “Chakai-Ki” was prepared and placed in the room, describing the participants, utensils used, and menu for the Kaiseki cuisine. The intention behind it was to make guests read what was going on in the Chaji on the first day and the relationship between host and guests from the vestiges. Visitors became participants in the relationships that already existed through the act of reading the vestiges.

This two-day set was conducted three times for a total of six days. The whole event is collectively referred to as “年ごとに 人はやらへど目に見えぬ 心の鬼はゆく方もなし WHITE2BLACK 11072023” (The waka poem means; Year after year, people perform the ritual to drive Oni away but they never notice that an invisible Oni also exists in their hearts) produced under the concept: Information Transmission and its (Ingrained) Distortion.

–I visited on the day of “ATOMI” and it was characterized by many references to elements from subculture in addition to those icons of Japanese history such as Oni, Sugawara-no-Michizane, and Sen-no-Rikyu.

YAMAN: In the early stage of the planning, the work was meant to be composed of only three contrasts: Oni, Sugawara-no-Michizane, and Sen-no-Rikyu. Even now, the main components of the work are these three as representatives of “distorted and ingrained information.” While this became worthy of admiration as a conceptual work, I had a problem with how it lacked lightness and how narrow the spectrum of its beauty was. It seemed to be weak as a protocol that could be appreciated both in Asia and globally.

So I referred to “American Beauty,” a beautiful comedy film about de-stereotyping. However, since its theatrical release, I have interpreted it as a story about finding the American form of wabi-sabi, in which the protagonist dies just after achieving enlightenment.

I projected it as an alternative way of life (death) that goes against the “unfortunate destiny of Oni/Sugawara-no-Michizane/Sen-no-Rikyu” onto the work. Since the exhibition was initially composed from the viewpoints of the three “dissidents,” the work was too resentful and bitter. The reference to that film balanced that out. Another essential element of this film is the fact that it was released in 1999 when the relational art movement and SABIÉ, a group reinstated to continue to evolve Chanoyu established in 1988, were active.

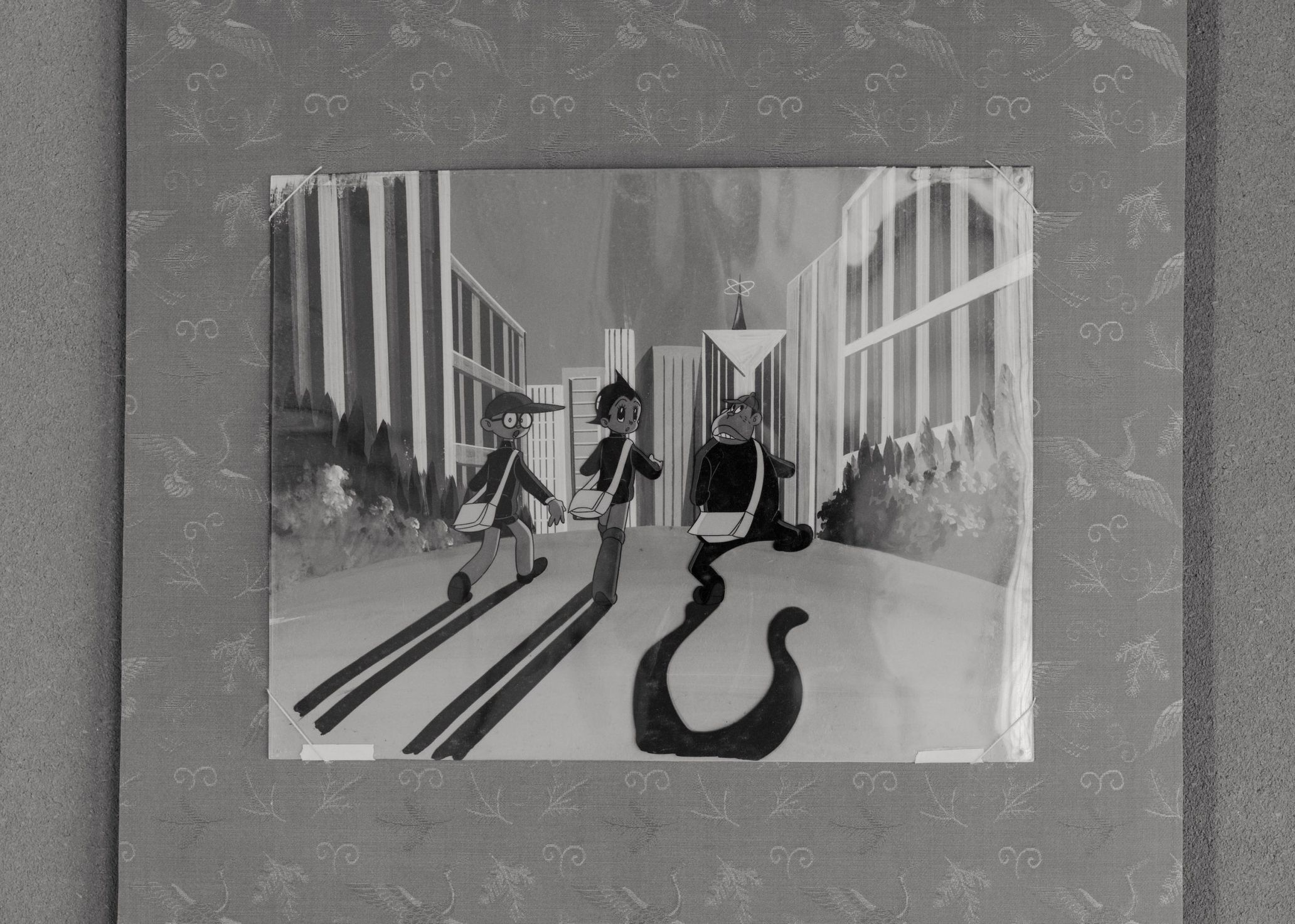

The same goes for Astro Boy. An animation cell of the black-and-white animated film “Astro Boy,” which began in 1963, and a tea bowl from my collection were included in the work. Displaying the animation cell as a hanging scroll completely changed the atmosphere of the entire exhibition. The use of the tea bowls with the image of Astro boy in the tea ceremony also added a sense of relaxation amidst the tension. In addition, as an idea I had been working on, I tried to juxtapose “Oni” with “Astro Boy.”

Astro Boy in the 1960s is not just a story of rewarding good and punishing evil. Racism and minority issues are well depicted. While robots are set up to have emotions equal to humans, they are not allowed to compete or fight equally with humans under the law of the “Three Laws of Robotics”. In a sense, we can overlap the structures of respective episodes of Astro Boy with actual cases of racial discrimination. There are many stories in which Astro boy is discriminated against as a robot or plays the role of the dissident.

In addition, the Astro Boy animated series, released in 1963, began to be broadcast in Korea in 1970. As was often the case at the time, I learned that some Koreans thought it was an animation produced in their own country. Also, many look-alike works were subsequently made in Korea. I was interested in pointing out this fact in a pan-Asian context and in relation to the concept of my work: Information Transmission and its (Ingrained) Distortion. Rather than judging whether it was good or bad, I thought it was a fascinating story that could be contrasted with the black-and-white animated “Astro Boy” being the first example of animation character copyright protection in Japan. I thought that the question of who the rules and schemes are for would be a question that could be linked to the “Japanese tea ceremony.”

–A pair of sneakers were included as one of the exhibits in this exhibition, as in the previous one.

YAMAN: I feel attached to Alessandro Michele’s Gucci, partly because I was involved of 2016 Cruise Collection. I like his philosophy and creations. One of the collections that manifested his philosophy was the “Fake Not” collection, and I sympathized with the concept. I have been embedding these sneakers in my work at every exhibition so far, as they overlap with the message I want to convey.

Another thing is that I always place these sneakers in places where visitors take off their shoes, such as shoe racks. When people see these shoes, they imagine an invisible guest, saying, “Oh, there is a visitor ahead of me.” “Oni,” which is used as a motif in every exhibition, has been defined in mythology as “something invisible” in relation to chinese character “隠/onu,” a word literally meaning “invisible.” I feel that Alessandro’s 2020 item evokes the “invisible guest” at the beginning of the exhibition, inviting guests on a journey into the more than 2,000 years of “Oni” history.

–Please tell us about “Oni,” the symbol that has consistently appeared in your works from your previous works.

YAMAN: The previous work was released in 2021. Unexpectedly, the exhibition was held under the declared state of emergency caused by COVID-19. The pandemic started when I was working on production. I reviewed the project in light of the changed environment, which ended up referring to “Oni.”

When you unravel history and mythology, you realize that the definition “Oni” has been used conveniently by human beings. At the time, I paid particular attention to the fact that one thousand years ago, epidemics were referred to as “鬼魅 (Oni and demons)”. Japanese people believed that Oni and demons brought disasters from the outer into our world. But at the same time Japanese people would enshrine and pray to them to avoid disaster. In short, with regard to the epidemics that occurred at that time, the Japanese people put both the cause and the solution on someone other than themselves, that is, “Oni”, “the outer”.

On the contrary, in the waka poem quoted in the title of this work, “年ごとに 人はやらへど目に見えぬ 心の鬼はゆく方もなし WHITE2BLACK 11072023“, it is pointed out that Oni exist “inside” of us as well. This must have been a groundbreaking perspective at the time in the Heian era.

In addition, as many of us know, “Oni,” which is supposed to be an old classical motif, frequently appears in modern works, such as “Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba.” And that makes me feel that this motif is compatible with my style, in which I refer to manga, anime, tokusatsu, movies, science fiction, and the Classics.

The explosive power of entertainment necessary to deal with serious messages

–On your Instagram, participants posted their critiques/impressions, and the author of the manga “JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure”, Hirohiko Araki commented, “At the end of the exhibition, there was more calligraphy on display. The characters said “咄々々” (totsu-totsu-totsu). The meaning is an old onomatopoeia like “ゴゴゴ (go-go-go, featured in JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure). Something is going to happen.” and scriptwriter Mitsuyoshi Takasu uses the keywords “puzzle solving”.

YAMAN: I feel that the motifs, including “Oni,” contribute to the formation of various links by themselves. On the other hand, my style also deconstructs and embeds classical motifs from a contemporary entertainment point of view.

I compose works in a multi-layered structure with many links and the “puzzle solving” element that accompanies it, inspired by the film director, Hideaki Anno’s way of thinking which I learned directly from him when I was involved in the movie “Shin Evangelion: 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Time”. I am also influenced by reference culture, which is different from that of contemporary art, and by the “ambiguous statement” approach, which is also unlike art.

Since my debut, I have consistently dealt with the concept of “Information Transmission and its (Ingrained) Distortion” and minority issues. They are not something for which I can quickly come up with the “right answer”, so I hope to create a situation where people feel something from my artwork.

Perhaps my career as a marketing strategist spanning more than 20 years has led me to believe this, but I feel that the world has become a place where it is impossible to enjoy a serious message without it having quick and entertaining elements. The more serious messages we have, the more entertaining elements we need. In that sense, I am relieved to hear and appreciate these words from two people I respect.

–I learnt that you have created your work in the form of relational art. Can you say more about it?

YAMAN: The work is based on the idea of relational aesthetics or relational art, a concept defined in Nicolas Bourriaud’s 1998 book “Esthétique Relationnelle.” The emphasis is on the interactions with the surroundings that occur in the process of the creation of the work.

What is called interactive art emphasizes the interaction between the work and the audience, but relational art emphasizes the interaction between the artist and the audience. The interaction itself is defined as the work of art, and the process of its creation and the audience’s participation are its essence.

One of the points of debate among critics since 1998 has been whether relational art can mirror “social relationships” and I believe the solution lies in the fact that the infrastructure of relation itself has changed, as I mentioned earlier.

–I found your exhibition rich and profound as it included so-called entertainment elements such as subculture and “puzzle solving,” but also used masterpieces valued at hundreds of thousands, or over a million USD, such as Chôjirô’s, and Nonko’s Black Raku tea bowl. Could you tell us why you focused on Chanoyu, the authentic Japanese tea ceremony culture for this exhibition?

YAMAN: My initial interest in Sen-no-Rikyu started in the era of Tom Ford’s “Gucci,” so 1990s, I guess. However, the more I researched, the more I wondered to what extent “Sen-no-Rikyu’s Chanoyu” as a way to seek “essence” has been handed down to the present day. In the first place, even information about Sen-no-Rikyu is often distorted.

In February of this year, I was inaugurated as the creative director of the SABIÉ, and I had a lot of discussions with Reijiro Izumi, the head of SABIÉ. And we came up with an approach that deals with “Chanoyu”, the authentic Japanese tea ceremony culture from an artistic aspect.

In “Chanoyu” there is a concept that is similar to relational art, in which the interaction between the host and the guests constitutes the work of art, as manifested in such phrases as “一座建立(Ichiza-konryu, meaning “perfect interaction” created by the perfect action of the host and the perfect reaction from the guests) and “主客一体(Shukaku-ittai, meaning “perfect ambience” which host and guests create together.) This led to the integrated project of a Chaji, an authentic Japanese tea ceremony, that is simultaneously a work of relational art that I mentioned earlier. Needless to say, it is meaningless unless it is the best tea ceremony from the perspective of “Chanoyu” as well. And good utensils are essential to reaching perfection.

On the other hand, Chôjirô’s Black Raku tea bowls were not classics when Sen-no-Rikyu chose them. As you say, it has now become an expensive work of art, but it is very doubtful whether Sen-no-Rikyu intended this current situation. I and Reijiro Izumi, the head of SABIÉ, decided to put aside the market theory and try to arrange good utensils that fit the concept; those were what we chose for this project.

–What led you to the concept of “Information Transmission and its (Ingrained) Distortion“?

YAMAN: First of all, although I describe it as “distortion,” I treat it as both a good and bad meaning. Sometimes good results can be formed through distortion. The point is that all information may be distorted in transmission and moreover, after 500 years, it is ingrained, and it becomes difficult to tell what is fact and what is distortion.

In addition, we need to develop a critical eye to speculate on what it means to have information from 500, 1,000, or even 2,000 years ago still available. In many cases, the will of the winners, the people with authority, and the establishment of the time, in other words, the majority, may have intervened in the process. There is certainly a difference between “historical fact” and “official history.”

This was true even for the interpretation of information before the age of information technology, so it is even more essential to examine the information from this perspective today when technology has quadratically increased the amount of information generated. On the other hand, just as memes sometimes add new points of view to the original information, it is meaningful to observe information and distorted information in juxtaposition.

–Conversely, is there any risk in using the Japanese tea ceremony, which has a 500-year history, as an example to express the concept of “Information Transmission and its (Ingrained) Distortion” which could be seen as a negative? What do you think about this as a creative director of the second-generation SABIÉ, appointed in 2023?

YAMAN: It carries a considerable risk (laughs). But I also think it is necessary to point that out. Above all, that was the honest feeling I had about “Chanoyu” regarding my own interest.

When planning this project, I had a series of discussions with Reijiro Izumi, the head of SABIÉ, about how bold our expression should be. He said, “You can make it unashamedly the solo exhibition of the contemporary artist, YAMAN NKYMN.” I was impressed by his comprehensive mind as a producer, and it reminded me that “Chanoyu” is weighted with 500 years of history.

We had 9 participants in the Chaji and 81 in the ATOMI, and I felt that they were all interested in both contemporary art and Chanoyu. The points of interest were different for each of the participants, but they all responded that they were difficult to enjoy, but at the same time interesting.

–Finally, please tell us about your future plans as a contemporary artist.

YAMAN: I felt that the expression as relational art, which I tried this time, has great potential. As I mentioned at the beginning, I am not a genuine artist. If anything, I am more like a bug, an irregular factor born within the social structure.

Since what I want to express is based on my career, high compatibility with the means of expression is the key. In this sense, I am happy to have found a language that suits me well. This time, we were joined on the first day of the tea ceremony by Theaster Gates, who will exhibit at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo next spring. We have formed an unexpected relationship with him and are hoping to collaborate.

I am making “(跡見:)追儺 黒節分/(ATOMI:)WHITE2BLACK” an annual event. I have already finished a filming with Perimetron for this year, as part of a project with “the outer” party that will take three years from 2023 to 2025.

–It sounds interesting.

YAMAN: The launch date of the film in 2023 has not yet been set. And I have not yet decided where and how I will hold “(跡見:)追儺 黒節分/(ATOMI:)WHITE2BLACK” in 2024 and beyond, but I plan to invite participants via my Instagram, as I did this year. I feel that the image of the artist that will be formed by the relationships, including these prospects I mentioned, is what I’m envisioning.

Continue to Vol. 2

Photography Kisshomaru Shimamura