“Visitors,” which started showing at Ginza Maison Hermès Le Forum in October, is an endeavor to connect the art-induced back-and-forth between reality and fiction by two artists working in different fields, Christian Hidaka and Takeshi Murata, through the perspective of a visitor.

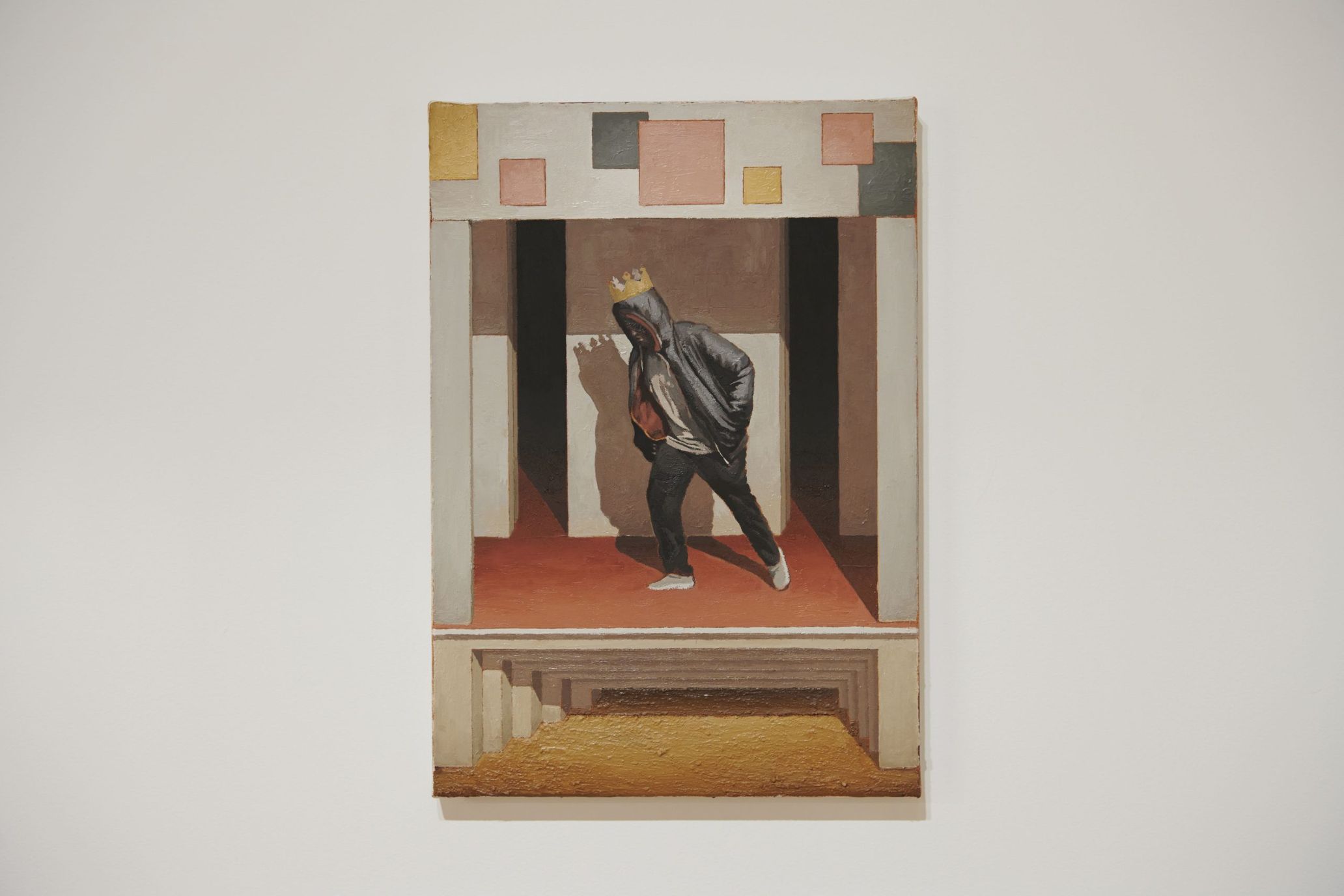

Christian Hidaka was born in Noda, Chiba, in 1977 and is a painter based in London. Made with his own blend of pigments, his paintings have a vibrancy and intricacy unique to tempera paints and are rife with references from Western/Eastern art history, theater, architecture, collective consciousness, magic, and personal memories. Hidaka’s paintings are a manifestation of illumination, perception, and the crossover of time and physical distance. The characters in his works—his motifs—could be considered metaphors of ancient times, recent times, and the present day. But you could also feel the warmth of his memories. For instance, Hidaka’s references to cubism by Picasso or Matisse, the costumes and stage design of Parade by the Ballet Russes, abstract Islamic motifs, and a Japanese-like woman come from different eras and subjects. However, his paintings have a still yet varied ambiance thanks to the artist’s use of distinct colors reminiscent of fresco paintings from the Renaissance.

Drawing from the theme, visitors, Hidaka used the entire exhibition space as one frame of a painting and completed the exhibition by going back and forth between his paintings and the layout of the space. Among his works are several time axes and scales that progress simultaneously. The visitor can walk through the exhibition and see the works from various angles and perspectives, which brings different space-time sensibilities to the fore. Rather than creating a conventional space where visitors look at paintings, it functions as a space where the visitor exchanges perspectives along with the experience. Moreover, the paintings, which the artist describes as Eurasian, utilize perspective and oblique projection techniques, a study of the state of the Eurasian continent, in which Europe and Asia coexist and share many nations yet remain separate. They’re one response to our world in which hybrid things coexist.

Takeshi Murata was born in 1974 in Chicago and is a cutting-edge glitch artist based in Los Angeles. His works, born from his interest in CGI rendering and decentralized digital media, capture everyday things from a different origin and present the shifts in reality as the weakening of the boundaries in space-time. Those who view his work will witness their (sub)conscious floating. Characters in familiar shapes fusing and dissolving in an immaterial manner and repeatedly growing and disguising themselves; a video where everyday landscapes are added with a collage-like effect and surreal dimensions; a no-fuss, still life in which Bowman from 2001: A Space Odyssey has transcended dimensions and landed in an unusual space that’s eerily similar to reality. The more alienated from reality, the more CGI becomes clean and mutable; it creates a subconscious reality.

The fixed idea that CGI equates to an isolated, parallel world that develops inside a computer screen has been long overthrown. Murata sometimes adopts a vanitas-styled still life while projecting videos onto screens in the city at other times. He also turns his works into sculptures sometimes. By doing so, the artist calls CGI into the real world and creates alternative opportunities for contact. At “Visitors,” there’s an interaction between Hidaka’s work and the exhibition space, and the visitor can delve into their own (sub)conscious world, which opens up in Murata’s works. We spoke to the two artists about their exhibition.

Chrisitan Hidaka

Christian Hidaka was born in 1977 in Noda and is currently based in London. In pursuit of a new form of painting, he paints his complex images using a method that links different eras and spaces. Hidaka creates Eurasian paintings, a hybrid spatial structure combining chiaroscuro from the West and oblique projection from the East to blend two cultures, and murals. His recent exhibitions include “Tambour Ancien” at Galerie Michel Rein in Paris in 2021, “Set for Four Players, a Sundial and a Bear” (with Raphael Zarka) at Fabian Lang in Zurich in 2021, and “Unhooked a Star” at the National Museum of Contemporary Art of Romania in Romania in 2018.

Takeshi Murata

Takeshi Murata was born in Chicago in 1974 and is currently based in Los Angeles. He’s known as a glitch art pioneer, where he adds visual effects by utilizing errors that occur when compressing videos. Murata sees CGI as a meditation on image-making and the digital afterlife. He explores his brand of realism by skillfully manipulating many digital media, from animation and film to CGI and NFTs. His recent notable exhibitions include “Living Room” at Yamamoto Gendai in Tokyo in 2017, “Infinite Doors” at The Empty Gallery in Hong Kong in 2017, and “Takeshi Murata” at Halsey McKay Gallery in New York and Kunsthall Stavanger in Norway in 2015.

Christian Hidaka: the process of creating paintings is art itself

–As the modes of artistic expression diversify, why do you continue to paint?

Christian Hidaka: Even today, there’s meaning in humans using their hands to paint. It’s not something you can automate.

I have a deep interest in the history of symbols, and making art with an understanding of the flow of the times is always in my mind. I’ve been following the historical art movements, from the Renaissance period to 20th-century cubism. In each period of painting history, each art piece is established as a complete work. For example, perspective drawing was invented during the Renaissance by people recognizing the viewer’s perspective. Oblique projection can be seen in Japanese and Chinese picture scrolls, where drawings on a flat surface develop into various time axes and spaces by stretching them to the side. I’m attempting to create a new type of painting by combining these different expressions. One of my artistic pursuits is to create works that don’t feel like déjà vu by using universal techniques in painting.

The biggest reason I continue painting is that the speed at which I make paintings match the rhythm and pace of my lifestyle. I spend a lot of time on each painting. Whenever I paint, I don’t use readily available paints. I create my own from pigments. The paintings are two-dimensional, but I layer around ten to 15 paints in one painting; I paint as though I’m making a building on a flat surface. My process, from making paints to creating paintings, is essential to me, and the process itself is a piece of work.

–What are your thoughts on the motifs in your paintings?

Hidaka: Many of my exhibited works are based on the theme of theatrical space, and I use paintings by other artists as motifs. Some examples are Picasso’s “Harlequin” from his rose-colored era and Cocteau’s ballet piece, Parade, for which Picasso did the art direction. Another frequent motif in my work is the Basel drum. At first, it was used on the battlefield during the Napolean era, but street performers in Paris started using it to gather a crowd. The drum can be seen in Picasso’s works, which I mentioned right now, and goes beyond space and time.

By scattering painterly motifs from various eras, from the Renaissance to the present day, the painting will continue to progress even after it’s complete. The painting is one foundation, and from the references scattered throughout it and by connecting to different times and places, my image expands. The characters are performing the original history of each artist’s work, using my paintings as a stage. Also, even if the other person has a different first language, we can share a mutual understanding if we have the same context. I’m very interested in expressing this effect through my paintings. Regarding the composition of my exhibited works, I placed the perspective diagonally, like in Eastern paintings, not face-on. Eastern paintings have a distinct sense of time and spatial structure; one trait is how they don’t draw shadows. I created a new sense of space in the paintings by adding three-dimensional shadows to an Eastern composition.

In the middle of Siparium is Medusa. I think of Medusa turning those who look at her into stone as a metaphor for her robbing their creativity away. If you look back at the mythology, the interpretation is that Perseus (man) had to cut Medusa’s (woman) head off to preserve creativity. In my version, the roles are reversed. Medusa is a man, and the woman uses a mirror as a shield to defeat Medusa. The world that’s reflected in the mirror is also flipped. Meaning everything is reversed.

This sort of expression can be effective because the viewer and artist share the same context. The #MeToo movement started when I began working on this painting, and I also thought about this issue deeply. I felt like women would turn into stone—be stripped of their creativity—because of the pressure they were under. The tale I’m referencing is ancient, but I knew a gender imbalance could occur in the present day, even if times have changed.

–What did you feel from having your exhibition in Japan?

Hidaka: Not only can anyone visit Ginza Maison Hermès Le Forum, making this exhibition a public space, but it also gives artists a space to try creating new works. This opportunity allowed me to challenge myself to create something I couldn’t in my studio.

My challenge was to express the exhibition space itself as a piece of art, and I could do that because of the existence of spaces like Ginza Maison Hermès Le Forum. I didn’t have a lot of opportunities to hold exhibitions during covid, so this was a wonderful experience.

Takeshi Murata: it’s not about going to and from a place—anyone anywhere can become a visitor if you take time into account, including the past and future

–How did you start becoming interested in digital media?

Takeshi Murata: I used to study film, but realistically, it would’ve been challenging to make films on my own since you need funding and other people to make them. Around that time (the mid-90s), some musicians used computer software to create noise and edit feedback sounds on the guitar. They approached music in an unconventional way. I imagined it would be fun to communicate that sort of noise through visual art in digital media. Besides, I could make digital media on my own.

In the beginning, I used the glitch effect, where visual elements were missing, and I would make errors on purpose. But as a result of testing out various digital techniques, I landed on making works using 3D software. I made still life-ish works using 3D CGI because you can create an unrealistic, immaculate look with the rendering process using software.

Also, I made my video art, Donuts, from videos I took of my wife, daughter, dog, and a neighborhood taco shop and donut shop that I always walk past. It was an experiment in the effects born from making a collage of everyday, familiar places on Dimension and making them look like a different space, like another big city.

My Larry series, my recent attempt at using simulation techniques, is an animation about a dog named Larry. He has somewhat of a nervous, unassured look and can’t control his body alone. I, the creator, have complete control of him. The aim is to apply real-life movements of objects onto CGI and construct a story that’s only possible within that world.

–What was the catalyst for you to develop an interest in sound art and noise music?

Murata: I went to Lollapalooza around 1994 because a friend of my friend’s mother got a ticket. Bands like the Smashing Pumpkins were popular then, but I couldn’t get into them. I was going through an edgy phase (laughs). Boredoms came out to the stage as the opening act. I believe it was part of their American tour. The venue was in the middle of nowhere in Denver, Colorado, and they played early, but there were only press photographers in the crowd. EYƎ-san from the Boredoms kept diving into the photographers because there was no crowd (laughs).

They made sounds I had never heard before. They sampled a kid’s piano and used instruments in a way you usually wouldn’t, and that was inspiring. That was the first time I encountered a new approach to music, and I still remember it clearly.

–Did being inspired by that sort of music have a direct link to your using digital media?

Murata: Yes. The inspiration I got from collages and noise music connected to visual art, like Shinro Ohtake.

I feel like the musical element in my works is strong. It’s like the direction of my videos and music are the same. With noise music, I like Hair Police from Lexington and Wolf Eyes—music from the 90s to early 2000s.

I’ve been collaborating with a former member of Hair Police, Robert Beatty, for a long time, starting with the soundtrack for my early works. When I was around 20, I said that I enjoyed trading CDs and works I like with others during an interview I gave to an online magazine. Robert read my interview and sent me a CD he made, and I sent him a video. That’s how our relationship started. It was like we were exchanging inspirations with each other. He also makes cover art. A recent example is The Weeknd’s album.

–How did you discover your sensibility, one that says that reality isn’t still but is rather fluid and can get dissolved and eroded?

Murata: Through producing digital media, I realized I could create hallucinations and psychedelic images I can’t consciously create every day, such as the flow of time regarding time and spatial awareness and sensibilities like the loss of things we take for granted. This discovery has influenced my understanding of reality.

On the other hand, compared to my younger years, I can now look at things from a universal perspective ever since I had my daughter and became a parent. Even in my everyday life, I can sense various circulations, the shifts of generations, and changes that occur with repetition. From this, I realize now that what I think is reality or the things I believe in can change and become suspicious or brittle.

How can I perceive things that can easily change in time and space? It’s not about going to and from a country or area. Anyone anywhere can become a visitor if you include the past and future, at any time. To cherish universal emotions beyond time and space and places that are your home or hometown; this might be the answer to this exhibition’s theme.

■”Visitors” by Christian Hidaka and Takeshi Murata

Date: Until January 31st

Venue: Ginza Maison Hermès Le Forum

Address: Ginza, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 5-4-18, 9th floor

Opening hours: 11 AM to 7 PM (last entry: 6:30 PM)

Closed: December 8th *follows Hermès Ginza’s business hours

Entrance fee: Free

Photography Shuhei Shine

Interview Akio Kunisawa

Translation Lena Grace Suda

Edit Jun Ashizawa(TOKION)