Hans Ulrich Obrist(hereinafter Hans):The first time I came to visit you, you told me you had played rugby before getting into art.

Pierre Soulages(hereinafter Pierre):Yes. I am actually friends with a few players who brought me balls. I have rugby balls here.

Hans:That’s great! Gerhard Richter once told me that paintings is bit like pétanque. So, I was wondering if there was, for you, an analogy between rugby and painting.

Pierre:As I understand it, yes. In rugby, the ball is oval. It’s important because you never know where it will bounce: to the right, to the left, to the front, to the back? And in research it’s always like that. In all research, even in painting. You never know where it will lead you. But I was not a great player.

Hans:But rugby was more important for you than the palm game?

Pierre:No, I have recently played the palm game. I have never been a rugby player, I was only playing when I was a student! What interested me in this sport, is that there is always something unexpected.

Hans:Is that the analogy? “In painting, the unexpected happens.”

Pierre:As in all research. It all depends on how we understand painting. I have never believed in theories before painting, they can only come afterwards.

Hans:Can we then say that there is no a priori, but only a posteriori?

Pierre:Exactly.

Hans:I would like to know how your art began, since rugby is not the beginning. You told me, during my first visit, that the beginning was prehistoric art, the finds of Aveyron.

Pierre:Yes. When I was 16 years old, I thought that the teaching we received was limited to a few centuries. I was going to museums and I was only seeing four or five centuries. In high school, we were taught about art as if it came from Greece, twenty-five centuries earlier. Our culture, the Christian era, represents twenty-five centuries. And I had seen the Antalya caves, which had been painted hundred-nighty-five centuries ago. So I said to myself: “But it’s incredible, we are focused on five centuries and it has been a hundred-nighty-five centuries since men paint!” By the way, a much older cave has been found since then. These questions made me wonder, why do men paint? Why do I want to paint?

Hans:That is a fundamental question, indeed. I have also read the interview you did with Zoe Stillpass for Interview magazine. You told her that already as a child you liked black ink.

Pierre:[Laughs] Those are childhood stories. I was a few years old, 5 or 6, I was dipping bread in the inkwell and when asked what I was doing, I answered: “Snow.” The contrast between black ink and snow made everybody laugh a lot; so much that they remembered it. But there were already telling this story before I was a painter. They thought I was an intriguing, original character.

Hans:This obviously has a completely different meaning today, because with computers the inkwell is disappearing.

Pierre:It is true, it is different. But black hasn’t disappeared.

Hans:Why this idea of working with black and white? Fleck explains in his text that we must not forget the post-war climate, which was very present. Do you think it has something to do with the war or the post-war period?

Pierre:No, it has nothing to do with it. When I was 5 years old, if I liked black, it was not because of that. I liked it because it is a beautiful color.

Hans:Did it come from inside?

Pierre:Of course. It has nothing to do with circumstances, no political significance. Besides, color symbolism was already abandoned at this time. It is an ambiguous symbolism: black represents mourning in our civilizations, but in most civilizations it’s white. When I was a child, I liked black because it is a strong color. When you put black with any other color, very often the other color becomes much brighter. When you put grey with black, it seems less grey, less dull.

Hans:What are your work habits? Do you paint in the morning, in the afternoon?

Pierre:What a question, I’m not a civil servant! [Laughs]

Hans:So you work when you feel like it? Because some artists and writers have a kind of ritual habit.

Colette Soulages(hereinafter Colette):That’s true.

Pierre:Not me, I work when I feel like it and when I can. Whenever I feel like it. Day, night…

Hans:It’s very interesting to know that you don’t have a regular schedule to work, that painting can come to you at any time.

Pierre:When I start something that interests me, I continue, and sometimes it goes on until three o’clock in the morning. One day, a friend was staying here and saw me awake at three in morning, I had just been working. So he asked me what I was doing, and I told him: “I’m going to sleep, but I am not sleepy. How about you?” He answered: “Neither am I, how about having a drink?” And we had champagne at three o’clock in the morning! [Laughs]

Hans:When you start a painting, is it often finished the same day or can the process be prolonged?

Pierre:Sometimes I work on it for a very long time, other times I work on it for a very short time and it’s already finished. But that’s what I like. The two excesses are being a civil servant – working fixed hours – or manufacturer. I am neither.

Hans:Your work is usually done at 360 degrees…

Pierre:Yes, my paintings are fixed, but if you move them around, they won’t be the same.

Hans:They are never the same twice, in the same way as stained glass.

Pierre:With stained glass, we can see the change from morning to evening.

Hans:Is it different with paintings?

Pierre:Yes, it’s different. The colors of stained glass change throughout the day; it’s interesting because it marks the passage of time. To mark the passage of time in stained glass is not innocent, it’s important: to know that time flows, that it is not the same in the morning and in the evening, it gives you food for thought.

Hans:The idea of time is already in your paintings, because they interact with each other.

Pierre:From the moment you work with light, you work with time.

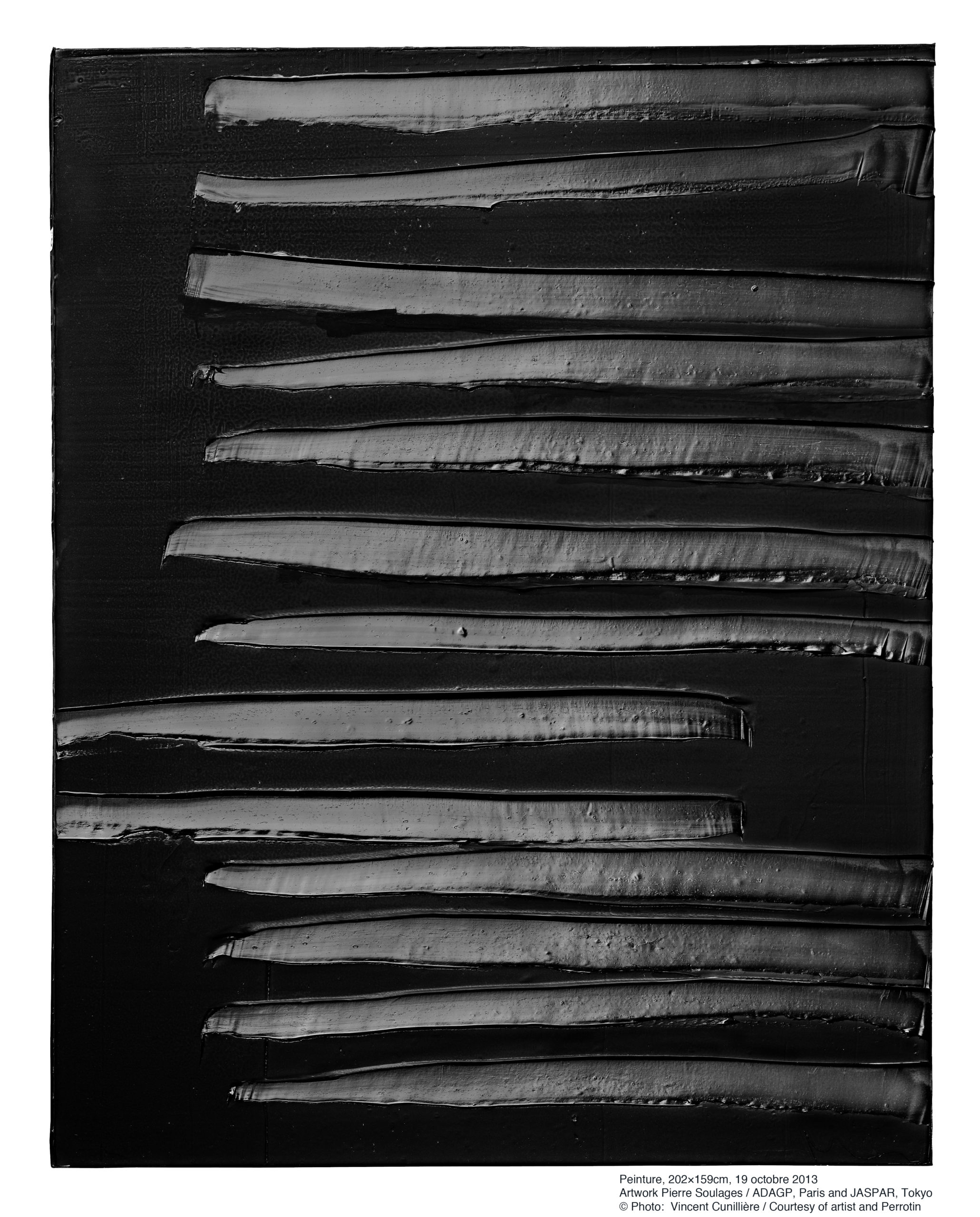

Hans:How did you come up with the name Outrenoir for your paintings covered with black? Is it a question of going beyond black?

Pierre:I was interested in this process because it’s optical, it’s a physical phenomenon and not an artistic one. Outrenoir designates an artistic phenomenon, the aesthetic emotion that this physical phenomenon provokes in us. What is aesthetic emotion? It brings us to a pleasure, that of dreaming. It reaches our mental field, everything that touches us. This brings us to another question: why do we love a painting?

Hans:Because it is produced to create emotions? It allows us to dream…

Pierre:Yes, but what kind of emotions? The fact that the mental field can be affected by this phenomenon interested me. So I thought it should be given a name, but calling it black was not enough. Outrenoir means beyond black, as outre-Rhin [across the Rhine] means Germany, or outre-Manche [across the Channel] means England. It is something else than black.

Hans:You just mentioned the idea of dream. In the interview with Zoe Stillpass, you said that today we need painting to live in a more interesting way, because it allows us to dream and to create emotions. So for you painting is not just pretty or pleasant, it is something that allows us to confront ourselves, to stand up. Can you tell us about this idea of confrontation?

Pierre:Painting allows us to enter into ourselves. One thing I couldn’t explain is the number of people who cried during my exhibition.

Colette:Not just frail people.

Pierre:Yes. A lot of people wrote to me that they had cried. The first time I was exhibited in Strasbourg I received a letter from a lady who had seen my exhibition. I didn’t know her, I still don’t know her, and she wrote to me: “I saw your stained glass in the Abbey of Conques. I was particularly touched to see how this 20th century creation fitted in with 2nd century architecture. I was so moved that I went regularly to Conques, I found it overwhelming. When I heard there was an exhibition of your work at the Pompidou Centre, I decided to go. When I entered the exhibition room, tears came to my eyes and the further I went the more I cried,” she says, “and when I got to the last room, I cried so much that I had to sit down.”

Hans:Beautiful.

Pierre:She concluded telling me: “I’ve been thinking a lot about why your work touched me so much. I think it’s because you did it with all your soul.” That’s a consideration that I would rather not talk about. Anyway, a few days later, I received a similar letter, and then others. I had received four of five of them when Alain Seban, the director of the Pompidou Centre at the time, contacted me and said: “I’m going to give a decoration to a man who gave a lot of money for the exhibition, could you attend?” I accepted, so I attended this award ceremony. Everybody was very elegant, women were well dressed, men had some decorations… At one point, I took the elevator to meet someone in the street. A man took the stairs at the same time, and came towards me when we were both downstairs. He was a young man, about forty-five years old, with a sporty physique, and he said to me: “Sir, I am glad to see you, I like your work very much.” I thanked him and he said: “I’ve been to your exhibition twice, and each time I cried.” I was so taken aback that a man looking like that would say that to me that I didn’t think to ask him who he was, I should have.

Hans:It’s disarming.

Pierre:Then we went to our respective cars. I thought it was amazing that such different people would have the same reaction. I spoke to Pierre Encrevé [Pierre Encrevé was a linguist, ministerial advisor and art historian specialising in the work of Pierre Soulages] about it, who replied: “They’re not the only ones, I’ve seen several people crying at this exhibition. One lady came regularly, every Friday.”

Hans:It’s very powerful because it’s rare in exhibitions.

Pierre:But the question is, why? I think it touched something deep inside them. Deep down, what is art? It’s not a simple construction, it’s really about something important, something capital, that lies beyond us. It is not a simple activity.

Hans:It’s very moving.

Colette:What surprises me a lot is the passionate interest that children have in Pierre’s paintings. It’s absolutely incredible.

Hans:This was seen in Beaubourg. I saw this exhibition, which was magnificent, and the audience was very young. There were a lot of children of ten or twelve years old.

Colette:Yes, they love it.

Hans:It’s interesting to point out something that Fleck describes in his book about the black and white in your paintings. He says that it’s like zero and one in the digital age, you see? So I wondered to what extend the advent of computer had changed anything. Has digital technology made an impression on you?

Pierre:The computer doesn’t change the sun.

Full interview published in Pierre Soulages by Robert Fleck et Hans Ulrich Obrist, Manuella Editions, Paris, 2017

Pierre Soulages

Born in Rodez in 1919, France. Lives and works between Sète and Paris, France. Experimenting with the color black throughout all his career, Pierre Soulages spreads the paint, brushes it, scrapes it, digs it out with his tools to create unusual light effects. Pierre Soulages celebrated his 100th anniversary last year. For this occasion, the Louvre museum held a retrospective of his work, including new paintings.

Interview Hans Ulrich Obrist

Photography Joe Hage

Artwork credit underneath the painting:Pierre Soulages / ADAGP, Paris and JASPAR, Tokyo ©Photo: Vincent Cunillière / Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin