Have you ever tried to listen to the sound of the city, the hustle and bustle?

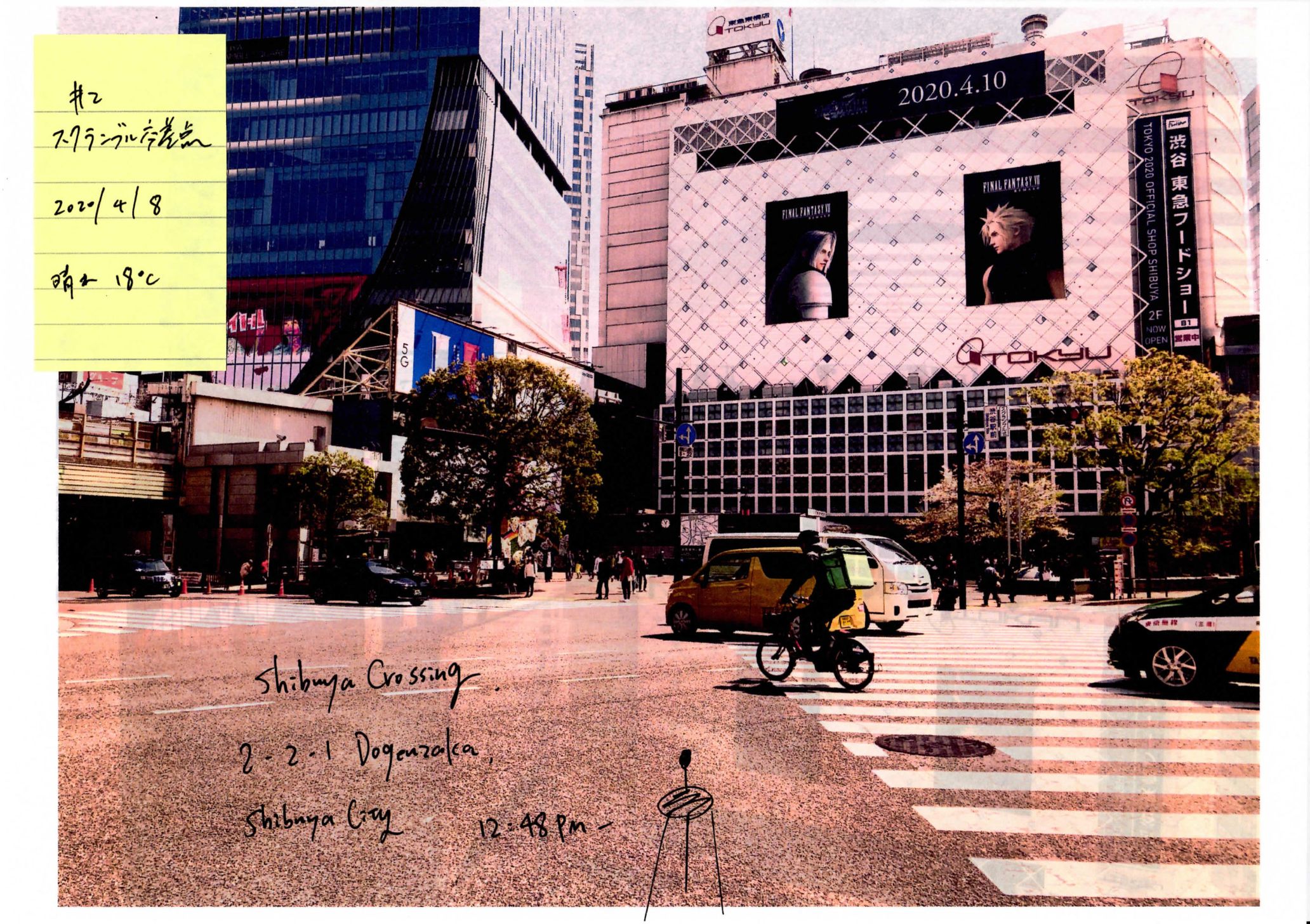

In the midst of the state of emergency, even Shibuya—the part of town that never really sleeps—was quiet, as if everyone had just disappeared. When it’s this silent, we come to realize that the word bustle actually means a layer of muffled sounds.

We can call Ono and Hasunuma sound observers and sound hunters. So, how do they listen to the sounds of the streets? Let’s take a moment to observe the sounds of Shibuya, standing between the concepts of listening and creating.

-Sound Study-

How the sounds of the city were created

Shuta Hasunuma:Environmental sound is like “going out to record”, isn’t it? It’s like holding a gun in your hand, or going hunting, or something like that, a so-called proactive act. But the truth is I’ve never really liked the idea of going out recording with a microphone, or looking for a specific sound. I have never really searched for a sound. I would hear something and be like, Oh, this sounds great. Sometimes I would take the recorder to the forest to observe something and leave it there. When I would come back an hour later I’d have something good. In this case, this was an interesting project for me because it had both elements of observation and newness, as I captured some sounds that I wasn’t expecting.

Seigen Ono:When recording natural sound, if you’re near the microphone, you’ll end up recording yourself, so I place the microphone, go away, and let it record for a few hours. I’m like an Okinawan longline fisherman with his net! [Laughs] But for this project I swung my “net” around as I moved about.

Hasunuma:It’s like going to a different place and coming back again. Ten years ago, I used to do field recording more often than now. Back then, I thought the listening part was more important than the recording part. Then you realize that there’s a difference between the sound you’re hearing and what it sounds like recorded. So you’re not doing it on purpose—it’s like the recorder is recording on its own—and it feels kind of neutral. I like that. When recording with a microphone, there are times when I accidentally encounter a sound, and I find these encounters interesting. The soundscape, if you will, is made up of all kinds of sounds, so instead of listening to it as a whole, there’s a way of doing it where we separate each sound and listen to each component individually.

Ono:I put on my headphones and see if I’ve got something good. It’s like if you take pictures with a film camera, you really don’t know what they’ll look like until you develop them.

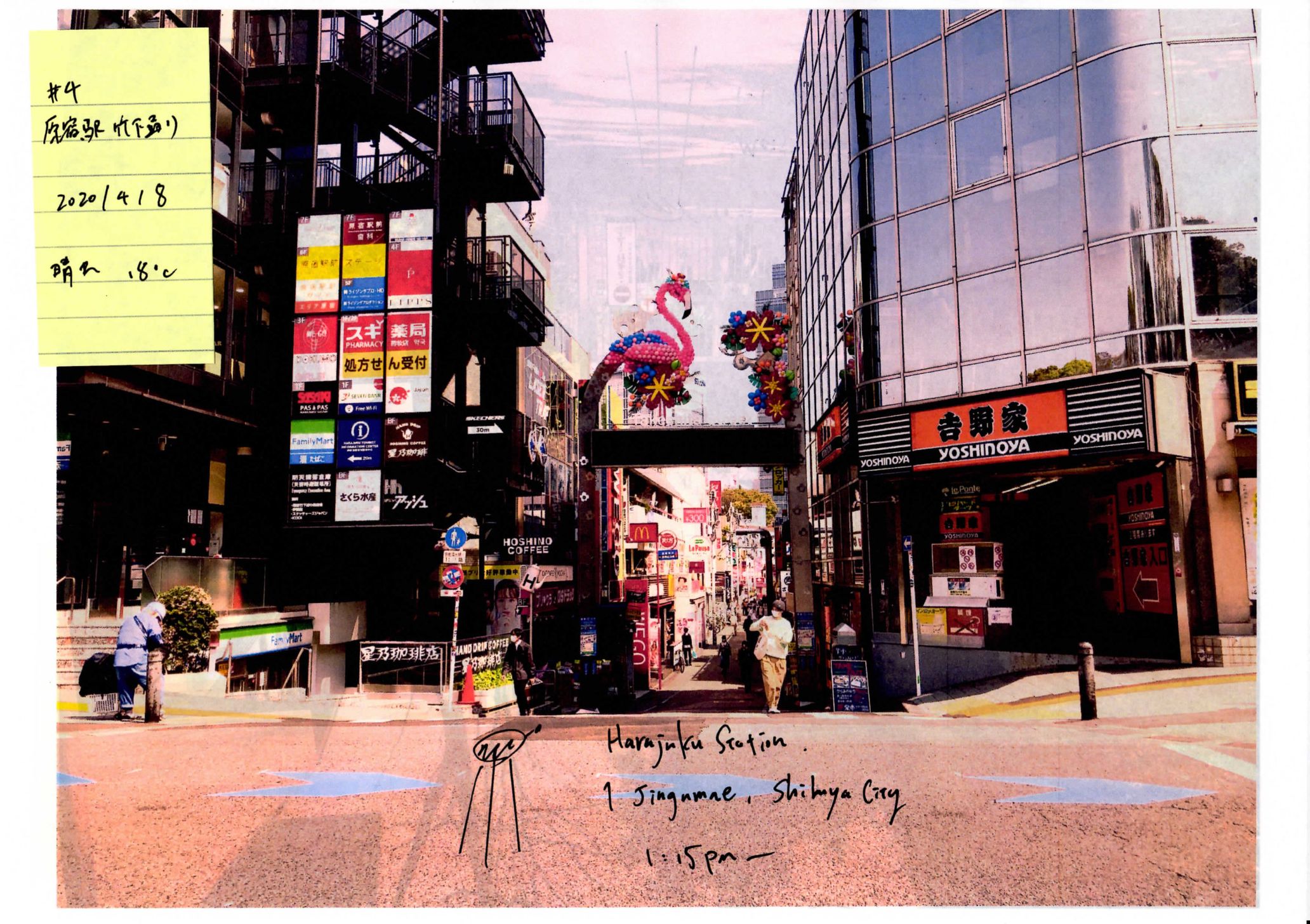

Hasunuma:These sounds were recorded the day after the state of emergency was declared, so I was actually more curious about observing the situation in the streets rather than spot-recording the city from my own perspective. Observing Shibuya, the center of Tokyo, was a bit strange. The sounds of advertising were reverberating so loudly at the Shibuya Scramble intersection! I knew this intuitively already, but I experienced it this time: when nobody is around, when we listen to the sounds of the street, we start to hear the different elements in the background as well as the sound design. I was overwhelmed by how the background sound of Shibuya is overshadowed by the sounds of advertising, particularly the pop music that resounds over the Center Gai area.

Ono:It’s like a live performance without an audience at Shibuya Scramble. Usually, the echoes are masked by the noise of the crowd. But because nobody was there, I could really hear the big echoes coming from tall buildings all in a row. We don’t normally hear this sound, and you could even say it was a bit scary! You could get a recording with really interesting reverberations if somebody were to play an instrument early in the morning or after the last train, when the advertising has stopped.

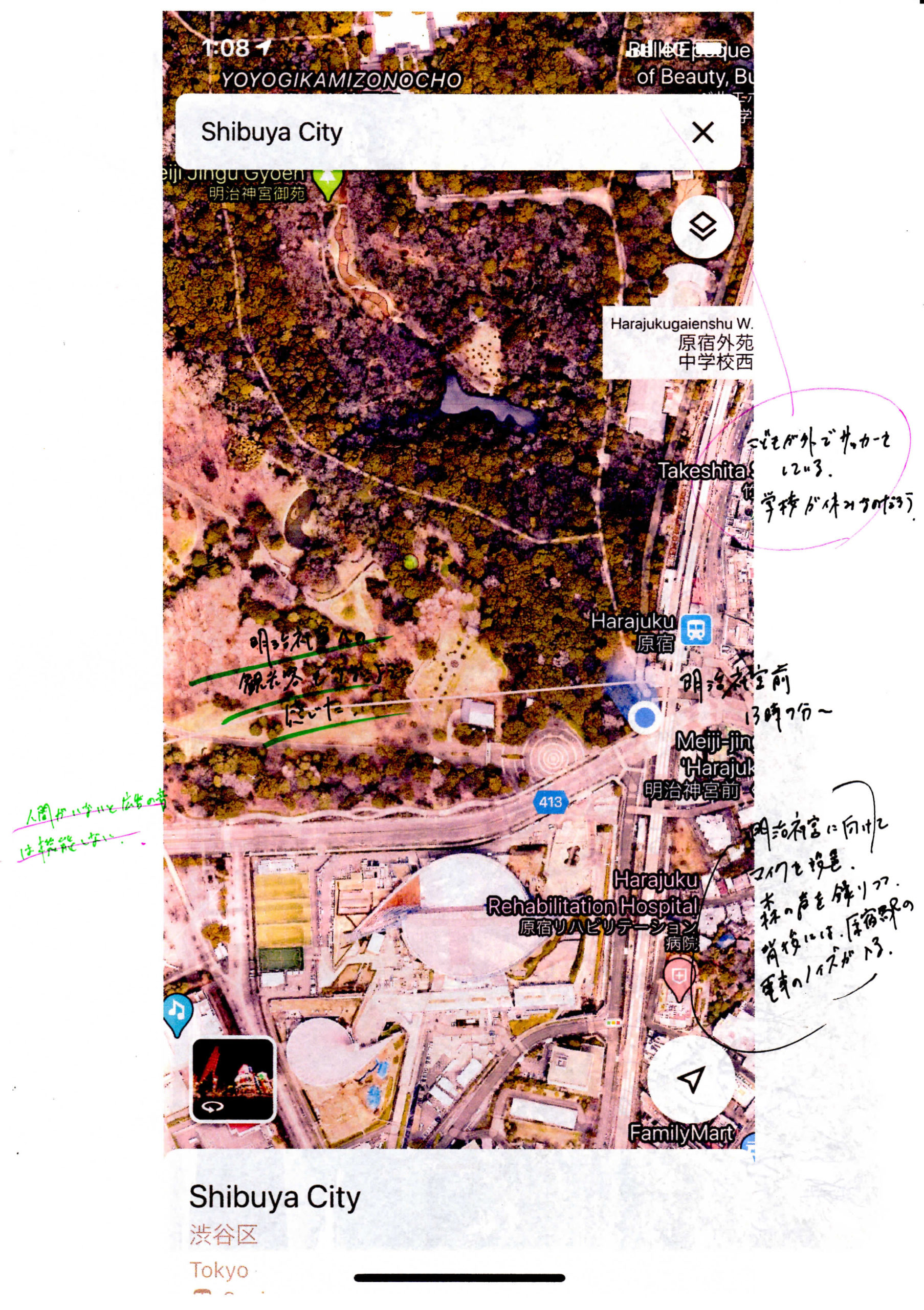

Hasunuma:What was interesting from a spatial standpoint was the Harajuku side of the Meiji Shrine. When I recorded the sound on the Harajuku side of Meiji Shrine with a microphone, the Yamanote Line was behind me. The sound of the train was not so much the sound of a train as it was the sound of an echo, so I was able to record the sound of the train behind it. It sounded like a nice sound from that direction.

Ono:So it’s like the forest of Meiji Shrine became an echo chamber?

Hasunuma:That’s right. And the microphone was facing towards the quiet forest, so I really liked that contrast.

Ono:That’s interesting. When people aren’t around, you can clearly hear the calls of the birds. This is the kind of recording that we can only get during this special time.

Hasunuma:Riding my bicycle in the city to record sounds, I really noticed how my attention goes toward what I’m hearing, even within a very short distance. For me it’s not so much about the texture or comfort level of the sound and whether it’s good or bad, but more about why we have this sound. I’m also interested in urban planning and why the sounds of the urban environment turn out like those I’ve captured here.

I feel that field recordings capture not only the sound but also the history of the land. Including the declaration of the state of emergency, I think it’s the accumulation of history that led to the sound we hear today… Observing the sounds and understanding the changes in them helps to unravel the history of the area.

Ono:That’s right, it’s about history. Speaking of urban design, the pavement of medieval villages in Europe was made of stone, as well as the buildings themselves. Once, I was on the road to a small village where I noted that the houses on opposite sides of the street basically faced each other. The road continued for a long while, with many bends and turns. The echoes produced a wonderful sound in this town. The center of the village had a church and a plaza, and a narrow road. Thanks to these stone buildings, which were 300-400 years old, the people went about their daily lives listening to reflected sound without even realizing it. This kind of sound is part of daily life in Europe in a way that it can’t be in Japan, since there are no stone structures here. It makes perfect sense that the New Wave music of the 80s, featuring gated reverb, with loud crashing and banging, came from the UK. I think this is the influence of the echoes that people heard bouncing off the walls in everyday life. A big difference with the paper-and-wood culture of Japan. In Brazil, events like Carnival as well as samba school practice happen in spaces like under elevated highways, or public areas between office buildings on the weekends. The reverberation between concrete structures is the perfect fit for the powerful sound of samba. In the end, the powerful sound of the drum is 70% of the echoes of a large space.

Hasunuma:If you lived in city like that since you were young, it is just natural. But when you become an adult and move to a different city, it’s interesting to realize how unusual your childhood experience was. The memory of footsteps is tied to the feeling of the soles of our feet on the stone pavement. So, everyone’s experience is unique. Lately, with the globalization of the world, asphalt is becoming more and more common, and footsteps are becoming more and more homogenized. It could be said that percussion instruments in music are trying to reproduce the character of these footsteps.

-Map of Sound-

The relationship between Sound and Memory

Ono:In terms of the relationship between sound and memory, the so-called sounds of the forest and the ocean are stored in our DNA. Even people who did not grow up by the sea find it relaxing to listen to the sound of the waves at the beach. Though for me the advertising at the Shibuya Scramble intersection is a sound for the younger generations, for others it might actually be nostalgic! Some people who grew up in the city can’t relax without the noise of the city streets, or the sound of repeating background noise such as machinery including elevators, car engines, etc.

Hasunuma:Some people prefer rooms facing the street. [Laughs]

Ono:And some people have childhood memories of the train running right next to their apartment building!

Hasunuma:I suppose the way you perceive sounds is influenced by your experiences and your literacy. So the sounds that a person was making or listening to are not always the actual sounds. I think that sound information contains a lot of memories of the place where we grew up, and they are mapped together with our memories.

Ono:The concept of mapping reminds me of a Polish movie called Imagine. The main character, who is blind, walks through the streets of Lisbon with echolocation, clucking his tongue. And as he goes along, the reflected sounds (echoes) keep changing with the walls, houses, cars, and the environment around him. He remembers them as a map in his head. Even a click sound, such as a snapping of fingers, can produce an impulse response, which means that even non-disabled people can learn the technique with training. Visually impaired individuals, however, map the world around them on a daily basis using the sounds that bounce off objects, acquiring the ability to identify concrete structures, intersections, approaching cars, stores, etc., in the environment.

Hasunuma:I find Rebecca Solnit’s book Walks: A Mental History of Walking very interesting about the act of walking. Remembering space through sound and walking are closely related.

Ono:I agree. On my way to Shibuya last time, as I was changing trains from the Ginza Line to the Inokashira Line, a visually impaired person happened to be in front of me. It was really dangerous because suddenly there were lots of people coming at us. I had him hold onto my elbow so that I could guide him. I wondered why the Braille was in this particular spot amidst the flow of traffic in the station.The announcements are made in Chinese and English, and although there are multiple languages available, the sound is coming from all directions in the station, and you don’t really know right away which direction it is coming from. The transfer design of Shibuya station is problematic for the visually impaired. I was thinking about that while I was moving around and recording sound.

Hasunuma:There are echoes and sound bandwidths, too. Depending on the space, the sound bandwidth can be blocked. In certain places such as the bathtub, there is an echo and you hear the lower tone sounds. There’s a New York composer named Alvin Lucier, known for his composition Music on a Long Thin Wire, in which he stretched the ends of a wire across a room, recoding and amplifying the vibration it produced. The same thing is happening on the city streets right now.

Ono:Yes, there are frequencies that resonate with the size of the space. It’s easy to understand if it’s a square space, like a bath; we can just imagine there are strings there. It’s called standing waves, and sounds of the same pitch as a string in a space have a tendency to be emphasized. For instance, if we tap on the flooring, the smaller pieces produce a lower sound. For this reason, the flooring used in this studio is comprised of pieces of random size so that we don’t have the same resonance. The relationship between space and sound is a complex one. By the way, I did a binaural recording of sounds nearby Shibuya station as I was walking along. When you listen to it with headphones you can get a sense of the space.

Hasunuma:I was amazed when I listened to your environmental sound with headphones. [Laughs] Whereas Seigen is recording the sound while moving around, I have primarily been recording in a still position. I think both of us think that we’re not just recording: we’re exploring the idea of what it means to record background sound, and also what it means to listen to sound. But the differences in our approaches is evident in our results, and that’s what makes comparison interesting.

-Reverberation of the morning-

Inspiration for musicians

Hasunuma:I’m 36 years old and grew up in Tokyo. Speaking from my background, I hope that the sound in Shibuya will get better, meaning not only sound design. It would be nice if the architecture would also be better suited to sound. There are lots of station buildings in Shibuya right now, and it would be great to see auditory design in the same manner as architectural design.

Ono:It would be great to redesign the area around Oku-Shibuya, or “inner Shibuya.” In 2017, there was a lot of buzz about a crowd-funded restoration project by Tokyo University of the Arts: the musical sculpture exhibited by Toru Takemitsu (with the help of sculptor François Baschet), who was the producer of the steel pavilion at the Osaka Expo 70. It would be amazing to see an urban space design like this in Shibuya—a modern version of Baschet’s work.

Hasunuma:I went to all of the performances in Kyoto, Osaka, and Tokyo. The great thing about Baschet’s music sculpture is that everyone has the opportunity to be exposed to it. This concept of Bachet’s, which came about in the 70’s during the Expo period, is still relevant in 2020. It would be nice if we could make it.

Ono:Wow, you saw it all! There is this big new building in the area where Hikarie and Google are located now. I imagine that there’s space where interesting sounds are produced between the buildings there. I’ll have to go there to find out.

Hasunuma:That’s right, I think there would be good places around there.

Ono:In terms of time, there should be interesting sounds in the middle of the night after the last train, or in the early morning. During the 80’s and 90’s, I’d often drink until 5 am, and I found that the sounds of the morning before and after 8 am differed greatly. After 8 am, the morning rush begins with commuters getting to work as well as children going to school. At 5 or 6 am, there are hardly any people and it’s quiet enough to hear reflective sound, or sounds coming from far away.

Hasunuma:Yes, that’s right, there is definitely a sound of the morning, a vibration of the morning. We’ve been talking about space and acoustics and even the time axis. It’s through complex combinations of these elements that art pieces are created. Yet when it comes to sound, the main thing is the listener. We can even say that in a sense it’s the listener who makes the music!

Ono:Now all you need is a cell phone to record. I’d love it if our readers could discover their very own background sounds in the streets. It’s all about experiencing and noticing things we don’t normally see.

Seigen Ono

Seigen Ono launched his career with JCV in 1984 as composer and artist. In 1987, he became the first Japanese to sign a contract with Virgin Records (UK). He established Saidera Records in 1987, followed by Saidera Mastering in 1996. He has engaged in a wide variety of work, including joint development of acoustic technologies such as VR, acoustic space design, consulting, and more. He won the ADC Grand Prix in 2019.

Shuta Hasunuma

Musician and composer, Shuta Hasunuma formed the Shuta Hasunuma Philharmonic Orchestra as a platform for experimentation with a wide range of artists. Involved in a variety of projects including music, theatre, dance, and advertising, Shuta Hasunuma consistently takes an experimental approach to music from an auditory and visual perspective.

Photography Seigen Ono, Shuta Hasunuma

Edit Moe Nishiyama