Doctor Inaba spoke about the relationship between medicine and art in his book, “What Awakens Life: The Human Mind and Body.” As he stands on the frontlines of the coronavirus as a healthcare worker, he continues to search for symbiosis between medicine, art, and culture. How are they related? And what prompted him to incorporate traditional arts and culture into medicine in the first place?

――In your book, “What Awakens Life: The Human Mind and Body,” you talk about how art, medicine, and religion were once integrated. Could you talk about that in more detail?

Toshiro Inaba: Zeami was responsible for perfecting Noh as it exists today. In his Noh treatise, “Fushikaden (Flowering Spirit),” Zeami essentially says that traditional Japanese art is meant to bring a long, prosperous life and that the ultimate goal of all paths is to deepen our joy with age. Medicine also strives for us to live a long, prosperous life, so I was surprised to hear that medicine and Noh share the same ultimate goal. Medical knowledge and technology exist to help people feel joy and happiness within their lifetimes. Healthcare professionals find joy and satisfaction in this process, too. In this sense, I believe that the secret of Noh can be found in both medicine and art.

――What initially drew you to Noh?

Inaba: At first, I just felt incredibly drawn to Noh for some reason, though I didn’t understand it. I wondered why Noh had been around for over 600 years. Then, in 2011, right after the Great East Japan Earthquake, I went to the affected area as a medical volunteer. When I witnessed so many lives being lost, it was impossible for me to reconcile the field of medicine, at least as it was up until that point, with the reality of what was happening. It didn’t sit right with me. At that time, I suddenly saw the Noh actor’s masks and heard the echoes of their chants coming from the depths of my soul, like a rumbling of the Earth. I was also searching for the meaning of “chinkon,” (pacifying the soul) which may be why I was drawn to Noh, which explores the intersection of life and death.

――So you adopted the concept of “Noh” into your medical practice after the Great East Japan Earthquake?

Inaba: I think on a subconscious level, Noh entered my life in other ways, too. I decided to practice medicine with a deeper understanding of life and death as a whole, rather than only helping on a surface level. After all, the deeper we go, the more humans can connect with one another. At the time of the earthquake, I thought that we would begin to fix the problems of our man-made world, but not much changed. So, 2011 really made me wonder if any change was possible without a fundamental shift in philosophy across the world. The current coronavirus situation is something that the world is experiencing in unison, so I think it could have a profound significance in human history.

――Do you think the relationship between medicine and art has changed in our current situation?

Inaba: I think it’ll become increasingly apparent that technology alone can’t fundamentally solve healthcare issues. We talk about the collapse of the healthcare system, but it’s really the collapse of healthcare systems that have been set up like factories, only meant to repair. Instead, healthcare spaces should be where we share the philosophy of life. This could look like a bathhouse, a gallery, or an art festival. It’s the intangible things, like shared philosophy, that really make a difference. Intangible things like philosophy can even make spaces feel uninviting, including the internet. This is a time where guiding philosophies are important to help us overcome hardship. In the future, if art is essential to our spirituality and social infrastructure, then this will manifest itself in various ways through the unconscious. Perhaps from now on, we’ll seek a more authentic way of life. A more human, noble, and beautiful way of life, rather than one that’s only rational, efficient, and calculating. In these critical times, art and culture can truly support our hearts and souls. We need to think about if we’re taking care of our health, and become more aware of ourselves and the world. Ultimately, even economic activity is only made possible by humans, so I think this is an opportunity to return to what it means to be human.

Healthcare’s next challenge: Designing a system that can be incorporated into our daily lives

――Why did you move to Karuizawa?

Inaba: I think medicine is a part of our daily lives and towns, and at Karuizawa hospital, they believe that doctors should be civil servants. This approach really resonated with me. I visited Karuizawa for the first time in September 2019, and I made the decision to move there immediately. My intuition came first, and I rationalized it later. Basically, I feel like my duty as a doctor is to work for the happiness of individuals and society. So, I think the details of urban planning, no matter how trivial they may seem, help build a foundation for medicine. You know, God is in the details.

―― I guess that’s the essence of your idea of restoring wholeness with medicine.

Inaba: The ideal space for medical care is a space where people can feel relief or just naturally recover from their illnesses simply from being there, without even having to go to the hospital. While there’s one approach to medical care that involves building high-rise hospitals and incorporating the latest technology, all of that would be destroyed if a natural disaster occurred. The next issue I want to address within healthcare is what kind of space we can share within our towns and daily lives.

――Though I’ve only been in Karuizawa for a short time, I already feel a bit cleansed. There aren’t any tall buildings. The sides of the narrow, intricate streets are lined with modern architecture that’s in harmony with the greenery. When I see the city’s streets in harmony with nature, I can’t help but feel that urban planning is also somehow related to medicine.

Inaba: The ideas and philosophies that underpin our lives are important. In the 1880s, missionaries came to the town of Karuizawa and built Western-style architecture here. Because of Karuizawa’s similarity to the North American climate, they planted birch trees. And they called Karuizawa “a hospital without a roof.” The nature conservation policy here says that the building-to-land ratio shouldn’t exceed 20%. For example, if you buy 1,000 square meters of land, your house has to be less than 200 square meters. And rather than fences, it’s recommended to have a hedge. In other words, humans have been given the privilege to live in nature. So, with this in mind, Karuizawa built a town that’s centered on nature, rather than humans. These guidelines aren’t legally enforceable and are left to the judgment of the town’s residents.

――Are the residents living up to their responsibilities?

Inaba: If you set the right standards from the beginning, people will figure out how to live within them. In society, when people are left to their own devices, their egos clash and they argue with one another. So, it’s important to create a little bit of a system, as a guide, that keeps human desires from getting out of control. If town planning is something that affects people’s health and happiness, then it makes total sense that medicine should be deeply involved in that process.

―― So, it’s about a wholeness that includes nature.

Inaba: As long as we exist on this planet, it’s impossible to ignore nature. The other day, there was a municipal employee mowing the grass, and the next day, he found all these bugs he’d never seen before in his house. It occurred to me that the coronavirus issue is like that, except on a global scale. In other words, if living creatures are deprived of their habitat, they’ll inevitably invade human territory. The same thing happens when viruses and parasites are deprived of their habitat. In search of a place to live, they’re forced to take up residence in humans themselves.

―― Maybe I shouldn’t say this, but I wonder if it’s karma for humanity.

Inaba: An essential problem of our society is thinking about where all living things belong. You could say that even bullying and violence are related to this issue. Everyone needs a place where they belong, right? In an interview with musician Otomo Yoshihide, he said that, “Music gives us a place to belong.” I really agreed with that. These days, there’s an increasing amount of people who don’t fit in anywhere. No matter how society changes, what new viruses are spreading, or if the economy stops, art and culture are something that give people a place to belong. Everyone needs that in order to survive.

――In building wholeness, what do you think is important?

Inaba: It’s important to know yourself. People don’t know themselves well enough. I’m inspired by how kids still have a sense of wholeness; when they play and jump, their movements are without hesitation or confusion. Although adults grow up and learn to fit into society, they also lose their wholeness. It’s good to be able to see the bigger picture of your life until now and understand your roots. You’ve come to many forks in the road and made many choices to get to where you are now. Maybe there were some paths you chose unwillingly, affected by family circumstances. But if you go forward with an understanding that everything is connected, even paths that seem disparate at a glance will eventually intersect.

Integrating the past and living in the “now” to reclaim your wholeness.

――Generally, I think many of us have made choices out of habit. The work of pursuing a path sounds painstaking.

Inaba: Of course, it’s hard. But no one is going to do that work for you. There’s no one else who can take your place in that. But reconciling with your past is part of life. For example, even if you regret choosing a path your parents told you to take, your life isn’t a mistake. Your past was necessary because it gave you the strength to push forward. However, if you still have even a sliver of regret, coming to terms with your past and integrating it into your present life is an important way of restoring wholeness.

――In your case, how has art been connected to your life choices?

Inaba: I made a conscious effort not to separate art from my life choices. I didn’t think of the medical path and the artistic path as separate. And when you do that, you meet other people who think similarly, because you’re both travelers on the same journey. That’s the beauty of life, isn’t it? But there are also people whose roots aren’t connected to where they’re at now. And even if you become aware of the misalignment between your body and soul, and repair the issue like you would a clock, a fundamental problem like that will keep recurring in different forms. I think it’s the role of a doctor to guide people like that back to their original path. People think it’s heresy when I say that, but I really think it’s the right way to practice medicine.

――I wonder if it’s because not many people think art and medicine are connected, since they seem like opposites at a glance.

Inaba: Medicine is also supported by intangible things like philosophy and thought. It’s really difficult for humans to truly know themselves, because when it comes to ourselves, we tend to have many blind spots. I feel that if you aren’t in touch with your life’s underlying philosophy, or your unconscious mind, you aren’t really living your life. People with an underlying philosophy that guides them are in harmony with themselves.

――How exactly would you define harmony?

Inaba: It’s about integrating the past and living in the now. Even if you put up a facade, you can’t escape your past, and if you live in self-denial, you’re living a lie. If we’re not in touch with our core, we’re fragile in the face of change and break easily. However, we can always get back on track. Nothing

is a waste, including the detours. And even if it seems like you’ve gone off track, if you can maintain your wholeness, you don’t have to take it so seriously. That’s what it means to recover your wholeness.

Toshiro Inaba

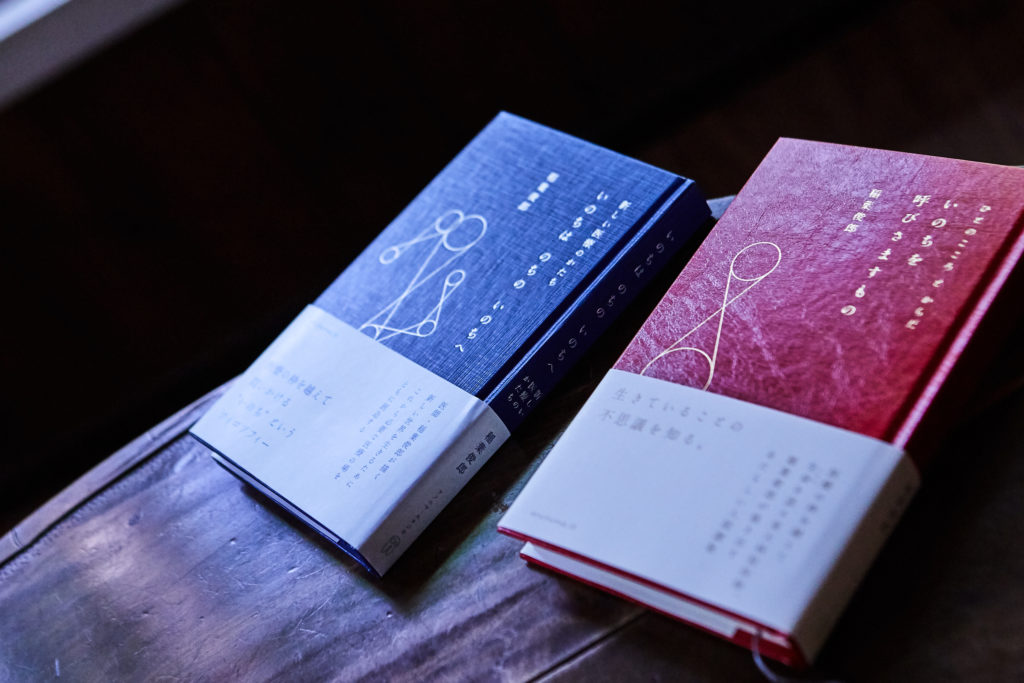

Born in Kumamoto Prefecture in 1979, Toshiro Inaba is a Doctor of Medicine. From 2014 to March of 2020, he worked as an assistant professor in the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at the University of Tokyo Hospital. From April of 2020, he became the General Manager at Karuizawa Hospital. In addition to studying Western medicine, he also has a wide range of knowledge related to Eastern, traditional, and alternative medicine. He’s also found overlaps between medicine and a variety of fields such as art, traditional performing arts, folklore, and history. Currently, he works as a visiting professor at Tohoku University of Art and Design. He is the author of “What Awakens Life: The Human Mind and Body.” (Anonima Studio) and more. His new book, published in July, is called “From This Life to the Next: A New Form of Medicine” (Anonima Studio).

Photography Kazuo Yoshida

Translation Aya Apton

Special Thanks Kyukaruizawa Café Suzunone