Since the release of his first solo album, “ATAK000 Keiichiro Shibuya” in 2004, Keiichiro Shibuya has continued to develop his sound without getting stuck in one box, as seen in his extensive and prolific catalogue of music. Think: sharp and structural electronic sounds, intricately lyrical piano pieces, exciting impromptu performances using various materials, vibrant and sensual Electro Pop, and emotionally provocative soundtracks. He goes beyond the narrow confines of music by creating sound installations at museums and operas that feature Vocaloids and androids. In other words, he produces stimulating works that point to the future. His vision of his new opera called “Super Angels,” set to be shown next summer, is a passionate one that will surely resonate with people from other countries too.

Here at Tokion, we’ve decided to start a series of columns regarding Keiichiro Shibuya. How does he face the ever-changing current times we live in? What does he see? We believe that knowing the answers could be conducive to thinking about the future of culture and society. For our very first installment, we have a long interview about “ATAK024 Midnight Swan,” Keiichiro’s first solo piano album in 11 years. We visited his private studio in Daikanyama to hear about his thoughts behind the project as well as how it came about. He also spoke to us about his roots and relationship with the piano.

“Fragmented” piano music; the polar opposite of “for maria”

——There’s an 11-year difference between your solo piano album, “ATAK015 for maria” (hereinafter “for maria”) and “ATAK024 Midnight Swan.” What sort of thoughts were running through your head when you started creating the latter?

Keiichiro Shibuya (hereinafter Keiichiro): They’re both solo piano albums, but I wanted to make something that was the polar opposite of “for maria.” I made “for maria” after losing my partner, so the entire album has the same mood from start to finish; it’s like an endless ocean with no waves. Sure, there are different kinds of tracks in there but the whole thing is enveloped in this overwhelming sense of stillness. I realized later on that I had actually created a pretty intense concept album. Some of the tunes were made for the album while others were written a decade before that time, back when I was really young. So, it’s also kind of like a compilation album with songs from and before the year 2009, which was a turning point for me. I wanted to create something completely different if I were to make another solo piano album.

——Wanting “to create something completely different” seems like an approach that matches your character.

Keiichiro: I agree. I’m interested in change. The album is partially influenced by the way people listen to music as well as the conditions that music exists in today. When I listen to music from 10 years ago, the first thing I notice is how there’s a lot of repetition. Most of the songs are 4~5 minutes long, which is longer than the songs we have now. Over the last few years, the length of a lot of songs have been reduced to 2~3 minutes. Further, we’re now seeing less rigid song structures that follow a certain formula, where there’s many changes within one song. Perhaps hip-hop and electronic music have gone through less drastic changes, but the message they want to convey is more concise. In other words, it’s become mainstream to have one message per track. I thought it would be interesting to respond to those recent changes with a solo piano album rather than electronic music.

——Normally, solo piano albums have a tendency to have a classical or pseudo-classical sound but it seems like your mind goes in the opposite direction. Your most recent album is also the soundtrack to Eiji Uchida’s film, “Midnight Swan.” Could you talk about how that came to be?

Keiichiro: This happens to me a lot, but I have luck when it comes to serendipity; whenever I’m thinking like, “I want to make so and so,” I get a job offer (laughs). As a part of my life plan, I wanted to release an album in 2019, ten years after the release of “for maria.” However, my android-opera project called “Scary Beauty” was finally starting to come together in 2018 and I had just began working on a new project, “Heavy Requiem” which was about mixing Buddhist music and electronic music together. On top of that, I became increasingly busy with making a new opera piece called “Super Angels,” which is going to be performed at New National Theater Tokyo. That’s why I wasn’t able to create and release an album then. In addition, in January of this year, we toured UAE for “Scary Beauty” and just like that, time had passed by in the blink of an eye.

It was in May of this year when I got approached to work on the music of “Midnight Swan.” Since I was so immersed in the making of “Super Angels” from the latter half of 2019 onwards, I was originally planning on only creating the main theme song. However, in June, it was decided that the first performance of the opera was going to be postponed to next year due to the pandemic. So, I was able to secure a week to work on the music for the film. That’s when I made the decision to produce the entire soundtrack. I realized that soundtracks have a fragmented form to them because the tunes are different according to each scene in a certain film. Because I was asked to make a soundtrack using the piano, I felt like I was presented with the best opportunity to create a “fragmented” solo piano album with one message per track. I basically locked myself in the studio for a week to write and record the entire soundtrack. It took me about a year to complete “for maria,” so this album was different in that aspect too.

Striving to create the same amount of volume as contemporary pop music

——You intended to make an album that differed greatly from “for maria,” but were there qualities that didn’t change?

Keiichiro: The way I think about how the piano should sound didn’t change. The majority of solo piano albums are recorded so that it sounds as though you’re listening to it in a concert hall. This applies to classical music as well as jazz. But as a listener and especially a creator, I really don’t have any interest in that sort of “normal” piano sound. For me, the piano is an extremely personal instrument and it’s all about trying to express the intimacy that exists between the sounds and myself. I want the listener to hear the sounds that I hear when I play the keys. Alternatively, I want them to hear the sounds that I hear in my head. I want to express that sense of closeness you feel when you sit next to someone playing the piano. That hasn’t changed since “for maria.” At my studio, I use a method called DSD recording and I used that for this album too. I dug deep to find the best, optimal audio for each track by arduously adjusting the mic and utilizing my headphones.

——My first impression upon listening to the album was that it sounded very contemporary.

Keiichiro: This connects to what I said about song structures changing, but perhaps it sounds the way it does because of the sound volume and pressure. The general volume of music keeps on getting louder, no? There was a time where it was trendy to add the maximum amount of compression and audio limiting in order to get the loudest sound possible. The waveforms at the time looked like pitch-black seaweed; there was no ebb and flow and difference in the tone of the sounds. Today, the technology behind mixing and mastering is developing in a way that captures volume while maintaining all the small details. Here in Japan, there’s this tendency to have this sort of purist mentality, like “raising the volume is only for mainstream, mass entertainment purposes. It’s inexcusable because it gets rid of the details.” I question that way of thinking. For example, if you look at people like Travis Scott and Billie Eilish, you’ll see that the characteristics of their sound are clear while keeping an appropriate level of sound. I wanted to use a similar kind of volume in my piano music. In my mind, I imagined a scenario where somebody could stream my track right after a hip-hop song without having to adjust the volume. I didn’t want the listener to have to raise the level, as that’s just like expecting someone to pay attention to you mumbling in a small voice; they shouldn’t have to do your job for you.

——So, you wanted to update piano music in terms of sound too.

Keiichiro: Yes. I took a different approach from “for maria.” After I was done mixing the album with Toshihiko Kasai, we were talking about who should master it. And then we thought of John Davis at Metropolis Studios. Metropolis Studios is a globally renowned studio that works with the likes of Ed Sheeran. They’re known for mastering in a way that also works well with mobile devices and streaming services. He’s a truly outstanding engineer that has mastered music for people like U2, Primal Scream, Blur, and Dua Lipa. When I listened to FKA twigs’ first album, I was like “the sound quality is excellent” and so I looked up the credits and saw his name. I also read an interesting interview of his when he came to Japan, and hoped to work with him one day. Fun fact: apparently Justine Emard, who’s a video artist and long-time collaborator of mine, had sushi with John while she was in Paris for a project with Alexandre Desplat (laughs).

Drone and noise can be made with the piano

——I’d like to hear about the individual tracks on the album. The main theme song, which is also the opening track, has this sorrow and romanticism to it. Further, there’s a complex beauty in the way the melody, harmony, softness, and toughness all coexist. These elements really pull you into it. Was this track made first?

Keiichiro: Basically, yes. I singled out several keywords from the film, such as “crying,” “rain,” and “understanding one another.” I then created sounds that matched each keyword and the one track that has all those factors is the main theme song. However, there is a synchronized quality that exists between this track and the others. When the main theme song was complete until a certain point, I was like “let me break this part down so that it’ll fit into that scene from the film” and used said part to create another track. On the contrary, there are some bits from other tracks in the main theme song. There’s actually a very important motif that’s not in the main theme song. It’s like another version of the main theme song; there’s a certain sound lilting throughout the album in a way that doesn’t seem too obvious. I was able to come up with an underplot that I originally didn’t see in the film by creating the soundtrack in a planned manner.

——Like you mentioned, there are a lot of “fragmented” and diverse tunes on the album. Some of the songs that stood out to me were the ambient/post-classical-esque ones that had a gentle sway to them; it sounded as though they were floating in the air.

Keiichiro: I actually tried to emulate Hans Zimmer and Max Richter on “M2” but it doesn’t sound like them at all (laughs). I’ve tried to create something similar to other people before but I always end up with something wildly different. I’ve never succeeded in doing that, so I guess it’s not for me (laughs). Because I only had a week to complete the soundtrack, Eiji (the director) had to put his faith in me and let me do the work. However, he told me that he liked Brian Eno and Philip Glass beforehand and we were also able to talk about ideas so I had no difficulties working on the music.

——Some of the tracks have a drone music and noise music sound to them.

Keiichiro: Those sounds were actually all made on the piano.

——Really? I’m surprised to hear that.

Keiichiro: Most people think that the piano only makes a sound when you press the keys and let go. However, once you press a key without letting go, it could make a sound for a very long time. That long sound, the one that’s not necessarily loud, is also a piano sound. I think it’s totally possible to incorporate that unconventional sound in piano music. Of course, those sounds you mentioned were reversed and processed with a computer but all the sounds you hear on the album are from the piano; they’re not electronic.

Music and life are for change and growth

——I was able to really understand how your most recent album was made with a different mindset from other solo piano albums. I’d like to hear about your roots but could you talk about piano compositions or composers you used to listen to?

Keiichiro: When I first listened to “Études pour piano premier livre” by György Ligeti (1985), I felt a huge wave of shock. He played with all ten fingers a lot, which was almost unheard of back then. It wasn’t like he had any tone clusters or special playing technique either. It also wasn’t as if he played clashing sounds. And yet, he explored new territory with his piano playing. He had African music influences in there, alongside tribal music influences but they were used in such a unique way. I used to listen to and play his music a lot and I think I still have remnants of his influences in myself.

Recently, I’ve come to realize that Yuji Takahashi had a big impact on me too. I initially wanted to become a songwriter because of him. I saw a concert series of his that was based on Kafka’s novels when I was in middle school. I saw him play Bach with Haruna Miyake. I also saw him play a toy piano. When one of his electronic instruments died, he played the piano while we waited for the battery to be recharged (laughs). I was just a kid back then, but I thought he had so much freedom and it was so cool. It was such a formative experience.

——You played with Yuji Takahashi in a variety of ways since then. It’s very touching to hear you talk about him.

Keiichiro: Mister Yuji is a genius pianist but he knows how to create music sheets with one bar so that you can play it with one hand. At one point, he put the piano to the side and picked up a Japanese harp with two to five strings and founded “Suigyu Gakudan.” I believe his ability to do what he wants has affected me. He doesn’t overly preserve and protect his techniques and knowledge. Instead, he matches the other person’s level accordingly. His attitude of being able to throw something away at any given time has influenced me. I reckon we have music and life so that we can continue to change.

——You inherited Yuji Takahashi’s heart and soul and those things live on through you.

Keiichiro: I used to listen to him play Iannis Xenakis’ compositions a lot. I especially like “Evryali” (1973). He disregarded this idea of using irregular meters and syncopation simply for the sake of “creating complexity with the language of music.” He came up with new piano sounds within a 4/4-time signature or a sequence using a 1/16 note. I thought having that sort of attitude was really cool. I really dislike using irregular meters and seldom use them.

——Does that mean you’re against calculated, complex music?

Keiichiro: The more you use academic complexity in your work, the triter it will be. That’s something I have no interest in. I’ve always believed that there are instances where the sound of a pencil rolling across a desk could sound more beautiful than a highly technical chord. With that being said, it’s not like I want to be like John Cage. I’m also not trying to be a purist about noise music. If you randomly play a set of chords and it turns out to be really good, that’s a happy coincidence, no? That’s what I mean.

——Your ability to see beyond strict definitions is what makes you original, I think.

Keiichiro: I just don’t have this clique mentality. I never liked joining cliques and that hasn’t changed. Well, I guess you can say I have a lot of enemies because of it (laughs).

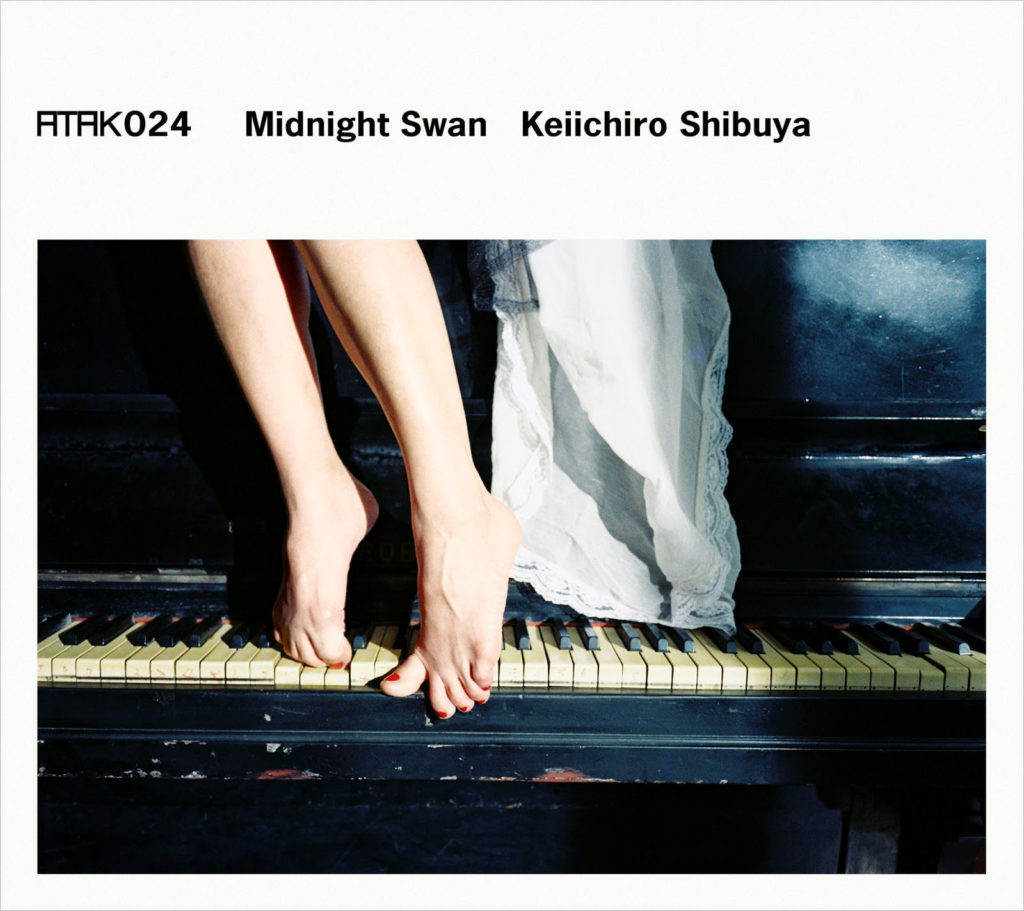

“ATAK024 Midnight Swan” by Keiichiro Shibuya

“ATAK024 Midnight Swan” is his first solo piano album in 11 years. He reconstructed all 14 tracks he made for the film, “Midnight Swan” into piano pieces. The cover artwork was made by Lin Zhipeng a.k.a No.223, who’s one of the most in-demand photographers from China right now. When Keiichiro went to a bookstore, he came across Lin’s photobook and felt like there was a similarity between the “fragmented” nature of the photos and soundtrack. Thus, he made a direct offer to the photographer. The photo on the cover is an old one but it looks as though it was taken just for “ATAK024 Midnight Swan,” as it matches the film, which is about a ballerina. Keiichiro says, “the photos on the back and inside of the CD booklet are from a photobook called ‘Grand Amour,’ which was commissioned by a Parisien hotel by the same name. Lin apparently stayed at the hotel for a week to take the photos. I discovered this later, but I felt like there was an affinity between the soundtrack and photo collection, as both were made in a week’s time. It’s interesting how you could find these little coincidences when you create a physical CD.” The album was mixed by Toshihiko Kasai and mastered by John Davis. Limited copies of the album are available to buy in advance through the official online shop for ATAK (https://atak.stores.jp), starting from September 11th (Friday) of 2020. On September 25th (Friday), the same day as the theater release of “Midnight Swan,” “ATAK024 Midnight Swan” will be available in digital form a la streaming services. Physical copies of the CD will also be sold on Amazon and Tower Records and such.

Keiichiro Shibuya

Keiichiro Shibuya graduated from Tokyo University of the Arts with a B.A. in Music Composition. In 2002, he founded music label, ATAK. His diverse soundscape covers areas such as cutting-edge electronic music, piano solos, opera, soundtrack music, sound installation, and so forth. He released a Vocaloid opera starring Hatsune Miku, which comprised of no people, called “The End” in 2012. The opera was shown at Théâtre du Châtelet and other places around the world. In 2018, he released “Scary Beauty,” an android opera conducted by an AI-operated humanoid android that sings along. This was shown in Japan, Europe, and UAE. In September of 2019, Keiichiro then presented “Heavy Requiem,” a marriage between Buddhist music and chants and electronic music, at Ars Electronica in Austria. He explores themes of humanity and technology as well as the border between life and death with his work. His new opera piece, “Super Angels” is scheduled to be released in August, 2021 at New National Theater Tokyo.

http://atak.jp

Photography Ryosuke kikuchi

Hair make Kosuke Abe (traffic)