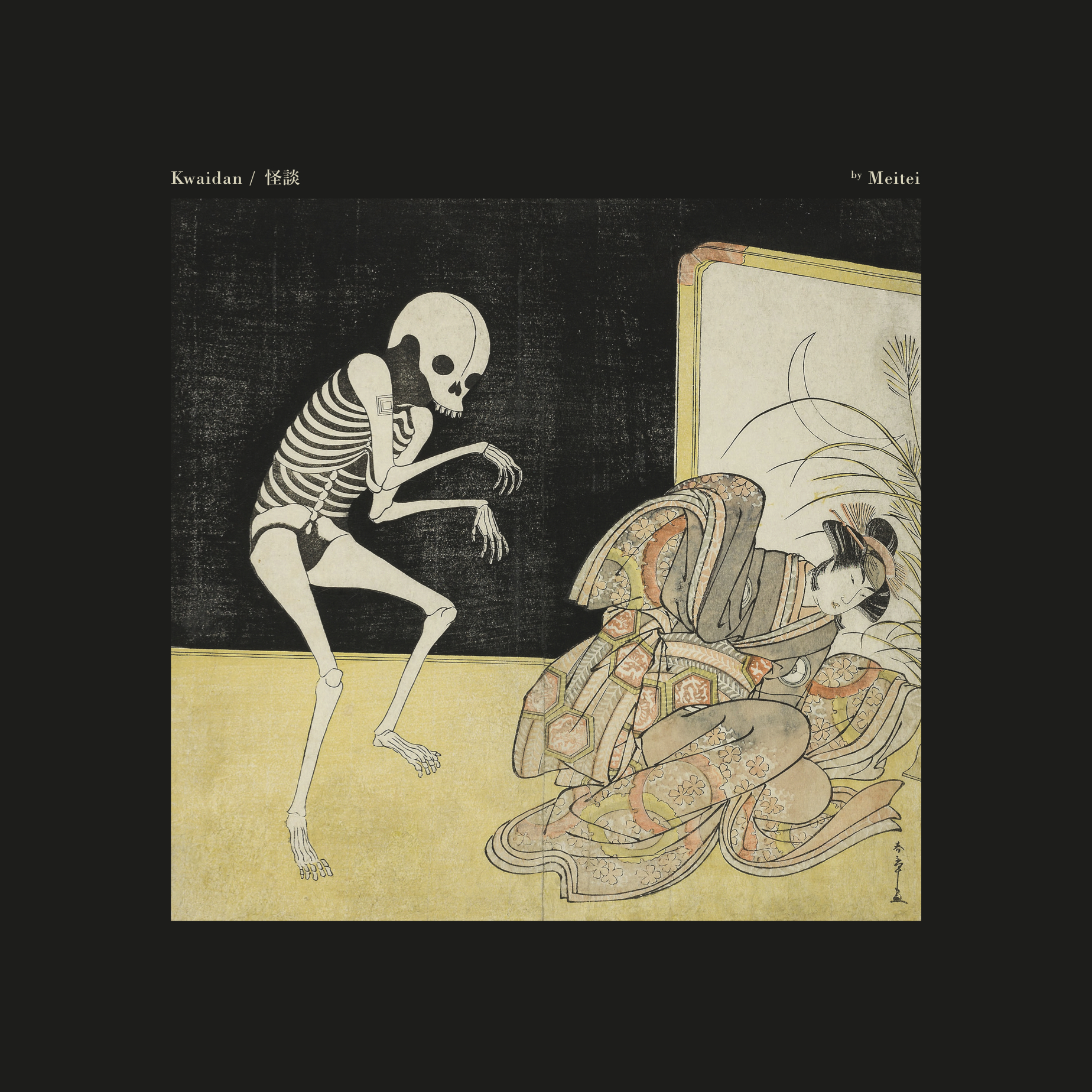

There’s a certain artist who released his first album, “Kwaidan” out of the blue in 2018, which was then selected as one of Pitchfork’s “Best Experimental Albums” of the same year. The following year he released “Komachi,” his second album, and received praise from listeners and critics both in and out of Japan. He’s one of the most talked-about ambient/electronic artists right now; and his name is Meitei.

For Japanese listeners, the unique “lost Japanese mood” he emits in his work sparks a feeling of nostalgia; it reawakens the collective memory. His music makes his foreign listeners feel a sense of both interest and sorrow for a culture that was lost, and he does this in a way that goes beyond the box of orientalism.

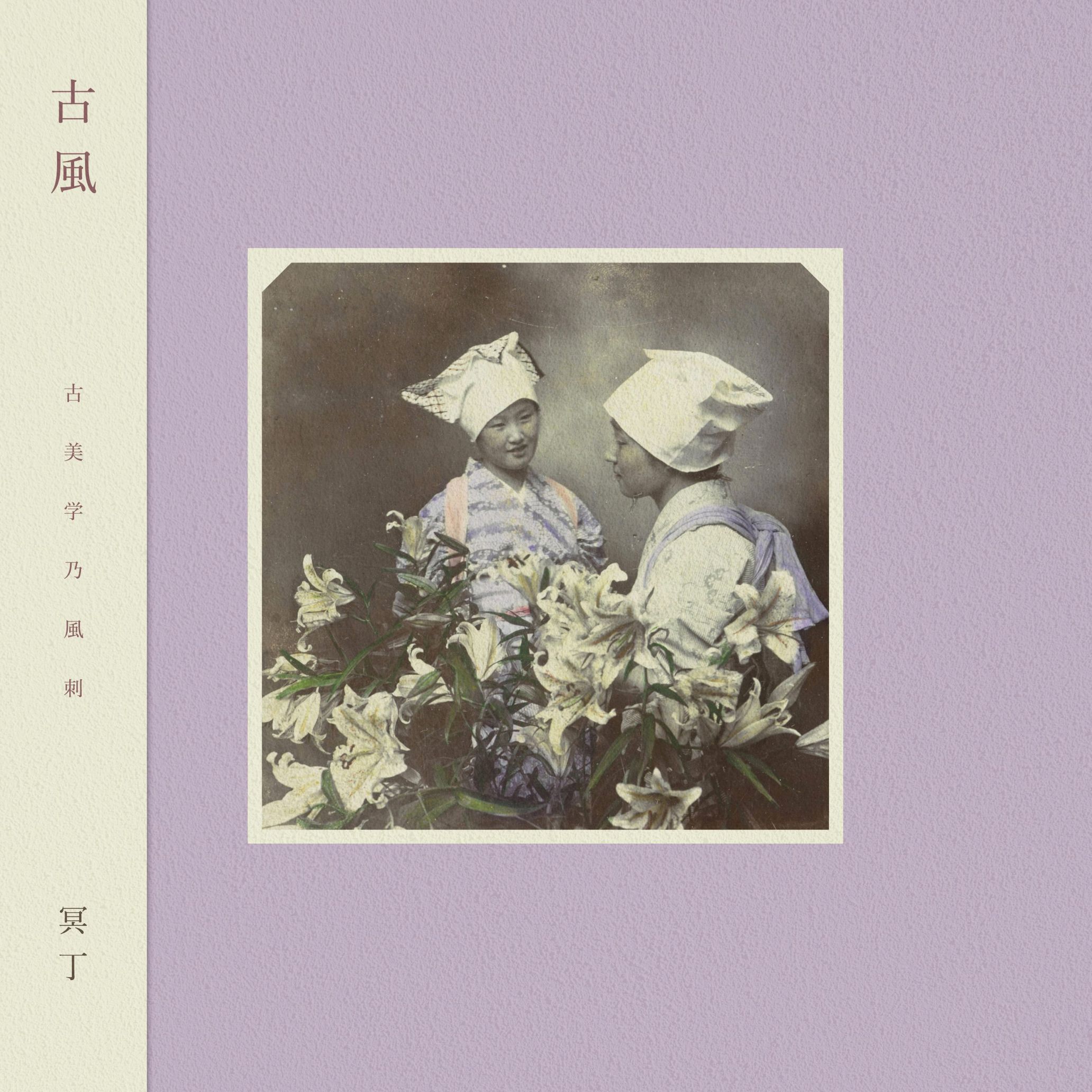

His latest album, “Kofu” is going to be released through notable Singaporean label, KITCHEN. LABEL on September 27th. It features old Japanese film and recording samples as well as beats that are reminiscent of Hip Hop. This project is an ambitious departure that incorporates techniques he hadn’t used in the first two albums.

The Hiroshima-based musician usually shies away from the spotlight and carries an air of mystery about himself. We sat down and spoke to him about his sonic history as well as what “ambient” and “lost Japanese mood” mean to him.

He starts: “I used to go to Esmod Japon and wanted to work in the fashion industry. It’s not like I was especially passionate about music. But when I was around 20 years old, I came across John Frusciante’s solo album, ‘Niandra LaDes and Usually Just a T-Shirt’ (1994) and I was so impacted by it. I went to buy a guitar immediately and from that point onwards, I became immersed in it.

After I graduated, I worked in an unrelated field for a bit. Around ten years ago, I made up my mind to be serious about songwriting. I was inspired by artists from Warp Records as well as other brilliant musicians and was still looking for my own voice. I would play the guitar in a peculiar way and record it on two cassette recorders. I then transferred that to a sampler machine to edit the sounds. I kept on developing that skill. I use a DAW software now but I’ve actually never touched a synthesizer before.”

Since then, he’s been creating music for the stage, as well as background music for stores as a professional songwriter. How did he get to the point of debuting as an artist with the release of “Kwaidan” in 2018?

“I had always made my own tracks aside from work, but I just never showed it to anybody. ‘Kwaidan’ was the first album that I was satisfied with, so I uploaded it onto Bandcamp and a Singaporean label called Evening Chants stumbled upon it and then released it. I was so surprised by how my work reached other people like that.”

Meitei’s acute understanding of the times and formative experiences that birthed “lost Japanese mood”

Just how was the concept of “lost Japanese mood” born?

He explains, “Most of the stuff I used to listen to was from different countries, and one day I redirected my attention to domestic music. I realized there was something that was off. Despite it being called ‘Japanese music,’ most of it has turned into ‘Tokyo music’ without us realizing it. When you listen to foreign songs, you can tell that there are different elements depending on the region, but with Japanese music, even if a certain artist lives outside of Tokyo, I feel like they try to create this sound that comes from a fictional, imaginary version of Tokyo. Even if you look at the roots of Japanese music, you’ll see that there are a lot of it belongs in the ‘Western pop music’ category. And somehow, that’s regarded as ‘Japanese’ music. I feel like our level of consciousness towards still-existing traditional Japanese scenery, like a snow-capped ‘Jizo’ stone statue or the reflection of the moon on a water surface in the countryside, is low.

I have this sense of anger towards this attitude of creating and playing ‘Japanese’ music without really, truly thinking about it. I thought it was only right for me to dig deep into history, and think about what it means to create music in modern-day Japan.”

It may seem challenging to access a “lost” Japan to channel that into sounds, but the artist states that his childhood memories are what made this possible:

“The house I grew up in was a very old house. Until middle school, we used to heat the bathtub by burning firewood, that’s how old it was (laughs). We had a storage room in the basement where we preserved grains and vegetables. My grandmother worked at a temple nearby, so I would go there with her every day to light up incense sticks. Living in that ‘Japanese’ environment was formative for me.”

Looking back at the past may cause one to fall into the depths of rosy retrospection (“Japan in the olden days was much better”). In other words, it could be one form of confirmation bias. However, Meitei rejects such warm, fuzzy feelings in his songs. Rather, his soundscape has a sense of urgency concerning the present. Figures such as The Caretaker and Burial come to mind; these British artists turn the notion of nostalgia on its head and carves out an almost ghostly, haunting world.

Meitei says, “My tracks have been compared to them before but I’ve never consciously tried to be like them. I only recently heard about The Caretaker from my agent when I went to a convention held in Barcelona in March (laughs). I feel like my music carries the old Japanese sentiment, ‘all things must pass.’ All things go through birth, decay, and death. So, it’s not as though I’m saying that we should preserve good, old-fashioned objects. I try to capture other stuff, such as the air surrounding some old, forgotten house in the mountains, the texture of spiderwebs in said house, and the yellowish color and smell of paper that the former resident left there.”

It could be said that the primary focus of “Kofu” is on the types of people that used to exist. Songs such as “Oiran Ⅰ,” “Oiran Ⅱ,” and “Nyoubou” are especially impactful, as the titles point to the roles of women in the past.

“I was so inspired when I looked into the lives of women in the Joo and Meireki period of the Edo era. For instance, courtesans that were popular in Yoshiwara were called ‘Katsuyama’ and there were high-ranked courtesans called ‘Oiran.’ I also looked into Otajiro Kawakami’s wife, Sadayakko (Kawakami). I couldn’t help but feel deeply empathetic when I saw pictures and photos of such women during that time. They had such fierce experiences and yet, they tried to live earnestly. My heart skipped a beat when I saw these photos that T. Enami, a photographer that was active in the Meiji period, took of women. Of course, there are many wonderful photos today but looking at his photos, you’re hit with the realization that there will never be anything like it. You can also easily imagine what sort of lives the subjects in his photo led.

Upon thinking about expressing the feelings I felt from looking at his photography, I discovered that the techniques I had used up until that point weren’t going to be enough. That’s why I decided to sample sounds from other parties. It was my first time doing it and at times I got so overwhelmed with emotion that I started crying.”

On tracks that blur the line between time and space, and the possibility of ambient/electronic music

In recent years, ambient music has made a big comeback in the scene and Meitei’s tunes get critically acclaimed in those spaces. What does he think of the term, ambient?

“To be honest, I didn’t know that ambient music was popular in the world until the people I work with abroad told me about it when I was about to release ‘Kwaidan’ (laughs). There’s a part of me that thinks it’s a bit intriguing that people look at my songs that way but another part of me understands it. I mean, my music tries to express unconventional matters such as old sceneries that existed in Japan a long time ago, so I get it. When I was making ‘Komachi,’ I went to Utano, Kyoto every night to think about how I could translate the air and environment there into sounds. In other words, the songwriting process began after I interacted with the actual environment and scenery. So, I do think my work has the features of ambient music in terms of that aspect. With ‘Kwaidan,’ before anything else, I aimed to change my environment so that it reflected the music. I lost over ten kilograms and let my hair grow freely. I only worked at night (laughs).

2.’Komachi’

But I do think ‘Kofu’ has some elements of Hip Hop. Some bits simply aren’t ambient. The label, staff, and I are all like, ‘so what in the world is this genre, then?’ (laughs).”

If the boundary between ambient music and its environment is ambiguous, then the same could be said about Meitei’s tracks. On top of blurring the confines of physical space, it’s almost as though his tunes could melt the realm of linear time. This exact quality is the idiosyncrasy of “lost Japanese mood” that continues to garner high praise.

Meitei says, “I feel like the possibilities surrounding ambient and electronic music are bigger than ever before. Whenever I listen to Japanese pop music, I can’t help but feel like the musician in question projects their intense thoughts or say, feelings of isolation a bit too much. It’s excessive. To me, it goes beyond the desire to convey a certain message; it sounds like they’re saying ‘please, please someone understand me.’ Such lyrics reflect the current state of society here, which is fragile and unhealthy. I believe being a musician is something sensitive people could do. Their words depict the reality of Japan. Since reality is hopeless, this inevitably leads to the lyrics being too self-conscious and brittle. When such content spreads far and wide, the feeling of hopelessness reflected in the music accumulates too. Isn’t entertainment supposed to provide comfort?

In that respect, electronic music doesn’t necessarily try to preserve that level of self-consciousness, to begin with. It offers a different perspective that exists outside of language, but it’s not the same as escapism either. Electronic music is an alternate way to incorporate wellbeing into one’s daily life.”

We asked him what he wants to do in the near future.

“There’s a lot of things I would like to do. Firstly, I want to produce music for international artists. I listen to a lot of K-pop and when I hear them sing in Japanese, it makes me feel more emotional than listening to a Japanese person sing in that Japanese. I think it’s because there’s none of that manipulation or hyper self-awareness that people have when they speak their mother tongue. It’s more like, ‘I’m going to sing this now.’ There’s a raw honesty there. I asked a Russian artist that I know to read one line from ‘Man’yoshu’ (an anthology of poems from the 8th century) and I felt this strange feeling that I had never experienced before. I reckon it would be cool to be able to express that with music.”

Meitei

He is a Hiroshima-based artist. To date, he’s released two albums on foreign labels: “Kwaidan” (2018), an album focused on the theme of ghosts and ghouls, and “Komachi” (2019), an album exploring the theme of nighttime. His music was used for the official promotion video for Sonar Festival 2020 in Spain. He also performed at MUTEK ES in Barcelona this March. He also produces music for a wide array of fields such as theater, films, and fashion.

Translation Lena-Grace Suda