“Miles Davis – Birth of the Cool,” a documentary on Miles Davis, the undisputed king of jazz, is now showing in theaters nationally. The impact his revolutionary music has had on generations after him has been discussed far and wide. However, there is something that hasn’t been studied as closely, and that is his relation to Japanese ambient music in the 80s.

In this article, Masaaki Hara, music critic and author of “Jazz Thing: This Thing Called Jazz,” delves into 70s era Davis’ proximity to ambient music, his intersection with Brian Eno, and the influence he had on Japanese artists in the 80s in regards to ambient music.

Where Miles Davis and Brian Eno meet

Right after his first recording session with Miles Davis, guitarist John McLaughlin said the following to Herbie Hancock, who was also in said session:

“I can’t tell. Was that any good what we did? I mean, what did we do? I can’t tell what’s going on.” (from “Miles Beyond: The Electric Explorations of Miles Davis, 1967-1991” by Paul Tingen)

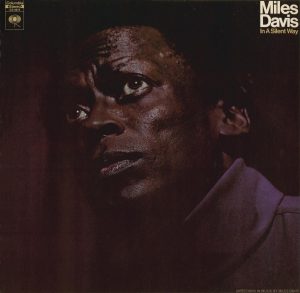

This took place during the recording of “In A Silent Way” (1969). The record is held in high regard and is seen as the blueprint of ambient music. It can also be said that he gave birth to music with more of an off-kilter sound. Alongside Hancock were musicians such as Wayne Shorter and Tony Williams, former members of the Second Great Quintet who had been on Davis’ side since his acoustic days in the 60s. The performance during the recording was vastly different from what they had been used to.

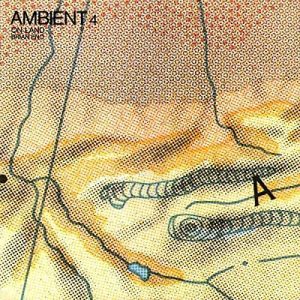

In his liner notes on “Ambient 4: On Land” (1982), Brian Eno wrote that “He Loved Him Madly” from Davis’ early 70s compilation album, “Get Up With It” (1974) and Federico Fellini’s “Amarcord” were major inspirations for his album. Eno stated that ambient music is “… related to a sense of place – landscape, environment…”

It’s not just Davis’ and the other musicians’ performance that Eno appreciates; it’s the production. More specifically, it’s the way each sound was recorded in certain spots in the studio, as well as the song structure and mixing. This is largely thanks to producer Teo Macero, who was in charge of recording and editing. Despite having an undeniable icon such as Davis in the center, the main sound you hear doesn’t come from a trumpet using a wah pedal. It’s only after around ten minutes go by when you hear the drums begin to maintain a steady rhythm. Moreover, the song sounds as though it’s being played in another room, and it ends with no other instrument taking center stage. “He Loved Him Madly” spans over 30 minutes and has what Eno calls a “spacious quality” throughout the song. The track was recorded in 1974, and the musicians involved were different from “In A Silent Way.” Guitarists such as Reggie Lucas and Pete Cosey were among them, and they understood what Davis’ wanted to do, musically-speaking.

When one looks at his use of modal jazz, a style of jazz that emphasizes less on chords and more on scales, as well as Gil Evans’ orchestral arrangement, one will see that it was only natural for Davis to progress in a way that eventually led him to off-kilter music. He took a break after this and made a comeback in the 80s. During the 70s, Davis was able to develop his music in fields outside of jazz and America. This brings me to my next point: his reception and effect in Japan.

On Miles Davis’ Reception and Connection to Ambient Music

“Kankyo Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980-1990” (2019) was nominated for a Grammy, which increased foreign interest in 80s Japanese ambient music. A portion of Japanese jazz musicians started to turn their attention to ambient music during that era. Davis’ music from the 70s and Eno’s music after that period were behind this shift.

Pianist Masabumi Kikuchi worked with Gil Evans from the 70s and during the latter half of the 70s when Davis was on a hiatus from the public, he joined a recording session with him, which was officially unissued. In the session were musicians such as Larry Coryell and Al Foster. I had the opportunity to interview Kikuchi in 1997 for a magazine and asked him about how “Susto” (1981), an album often regarded as one that carried the legacy of Davis, came to be. I also asked him about how he began using synthesizers and drum machines, as well as how he felt about going from mainly playing the jazz piano to synthesizers. Let me quote from the interview:

“I come from a background of playing lyrical, emotive music. That element is sort of limited in computer music or electronic music. So, when I tried to put in more of a lyrical feeling into that genre, it was hard.”

“Brian Eno! I was obsessed with his work and have all of his records from that time. He made me want to make music like that. But I didn’t have enough equipment and was also unsatisfied with what I had created. I just couldn’t pour my emotions into it, so I felt like something had to be done.”

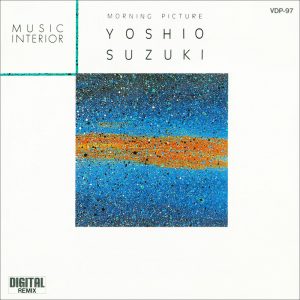

Kikuchi injured his finger in 1976 and became unable to play the piano in a way that made him satisfied enough, hence his transition to creating music with synthesizers. After releasing “Susto” and “One Way Traveller” (1982), he continued to produce more ambient music on his own. Around the same time, Yoshio Suzuki, a bassist that was previously in Kikuchi’s group who then moved to New York, released “Morning Picture” (1984), which he made alone using instruments such as the synth and drum machines. He was commissioned to create the ambient record, but Suzuki said that he tried to express Japan as a space in his own mind as well as the sense of cosmic space he strongly felt in New York.

Musicians such as Yasuaki Shimizu, who’s also critically acclaimed outside of Japan, and Jun Miyake, who was discovered by Terumasa Hino, had their debut boosted by the fusion genre trend in the 80s. However, these people distanced themselves from said trend and were digging deep to find their own style. The influence of Davis’ 70s era and Eno’s music were behind this too. By the 80s, which is also when Davis made a comeback, the kind of “lyrical music” that Kikuchi described was starting to become digitalized. It seemed as though there was no room for the “spacious quality” that initially drew Eno to Davis. However, if one listens to ambient music, minimal, improvised music, small ensembles, and electronica, one could hear the traces of 70s era Davis and Eno’s influence. Perhaps the people that paved the way were Japanese artists that created the space of ambient music. I’m sure of that now.

※1 Cited from Paul Tingen『Miles Beyond: “The Electric Explorations of Miles Davis, 1967-1991” 』

Translation Lena-Grace Suda