Soh souen is the new moniker for the up-and-coming artist formerly known as Hajime Kuwazono. In a world overflowing with digital tools, soh souen deliberately uses his body to create delicate hand paintings that express his interest in the body, the self, and the other. In his current exhibition, “A Modest Scream,” he “modestly screams” about the potential of art in the digital age and his curiosity towards both the body and painting as an art form.

I wanted to escape the prison of words

――You changed your name from Hajime Kuwazono to soh souen. What do you prefer to be called?

soh souen (Hereinafter soh): I guess soh souen-san or soh souen-kun or something.

――Why change your name now?

soh: I’d always wondered what a name even was. I guess you could say I was uncomfortable being defined by a word. I’ve been called by both my real name and nicknames, and I’ve responded to different names at different times, as if they were all an interchangeable way of describing me. When I was feeling worn out, mentally and physically, I went through a period when I wanted to escape from being called by that name. I want to escape the prison of words.

――Have you felt different since changing your name?

soh: My real name carries my bloodline, the land, and many other elements, so by actually changing my name, I think I was able to mentally distance myself from a lot of things.

――However, the person making the art is both “Hajime Kuwazono” and “soh souen.” Does that create any mental dissociation?

soh: Not at all. Because the fact remains that I, the living and breathing human being, am the one creating art as I go through life.

――Could you tell me about the interests, elements, and motivations behind your work?

soh: My work is based on my interest in the origins of the self. If I had to explain it in more depth, I’d say that I’m interested in painting as a way to explore the body, the other, memories, etc. [which make up the self].

――How did you become interested in the origins of the self?

soh: As a person living in society, I guess it was like, I had the fundamental questions of: How does society affect me? Or on the other hand, what am I to society? What does it mean to live as myself?

――By the way, what are some of the elements that make up soh souen as a person at the moment?

soh: Like everyone else, I have many identities and use various personas at different times. I think what ties these identities together is that I live in East Asia, in Japan, in 2020.

So first, there’s the time. I can’t separate myself from the reality that I live in 2020. And then, the place. The fact that I live in East Asia, in Japan, and in Fukuoka. I think that we can only understand ourselves by weaving together our past and place.

――You express yourself, the person who is made up of these elements. But why did you choose to create or paint as a way of expressing yourself when there are so many different modes of expression?

soh: I think painting is very interesting, poetic, and philosophical on many different levels. Like many other painters, I’m someone who was drawn to that charm. I’d like to pursue this over a long period of time.

I was expressing our small screams as beings who occupy bodies

――The history of painting goes far back. What do you think it is that draws people to it, regardless of era or generation?

soh: The history of paintings has continued into today. This is a big topic to tackle, but I wonder how to understand that accumulation of history and thoughts, and then turn that into paintings today. Or I wonder what form they’ll remain in for the generations after I die, or for other people. I’m conscious of wanting to pass the baton, or rather, I want to keep it meaningful.

Also, I do it as a process to organize my thoughts so I can understand myself. Painting is something you do with your body. I believe that this three-dimensional pleasure is inseparable from painting.

From the birth of photography to today, the identity of painting has always been in flux. I’m part of the generation that was born after people said that art history was done for, so that’s why I have a great interest in figuring out what I should do.

――Your solo exhibition, “A Modest Scream,” is currently showing. Could you tell me about the aim, concept, and meaning of the title?

soh: We live in an age where a lot of things can be accomplished or created online and virtually. I also benefit from that in my everyday life. My hope for this exhibition is that it can pick up the voices of the things we leave behind in our lives.

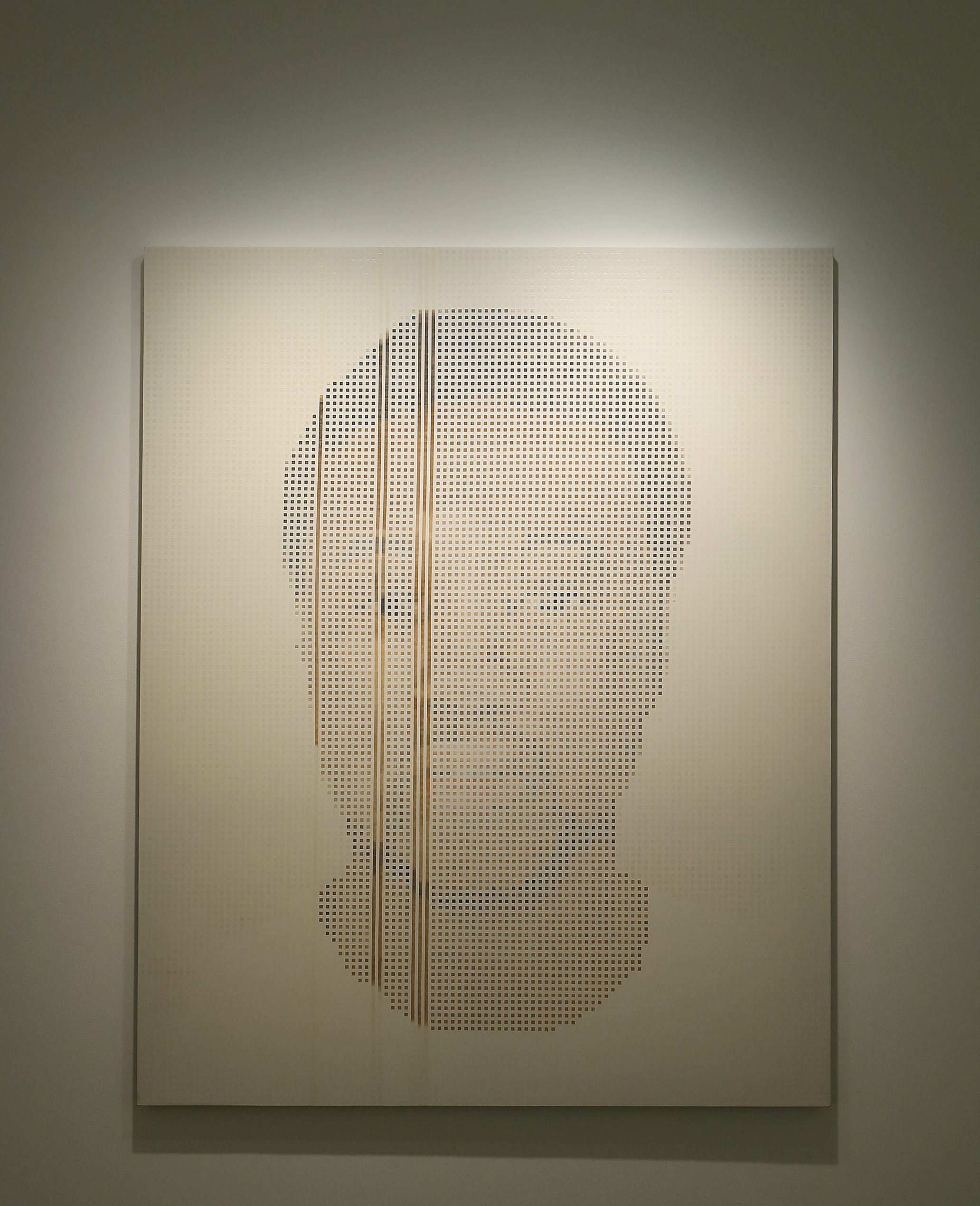

I think this exhibition was characterized by the fact that I invited the audience to engage with the art and the space with their bodies, whether those works were portraits, pastel pieces, or installations. I was expressing our small screams as beings who occupy bodies.

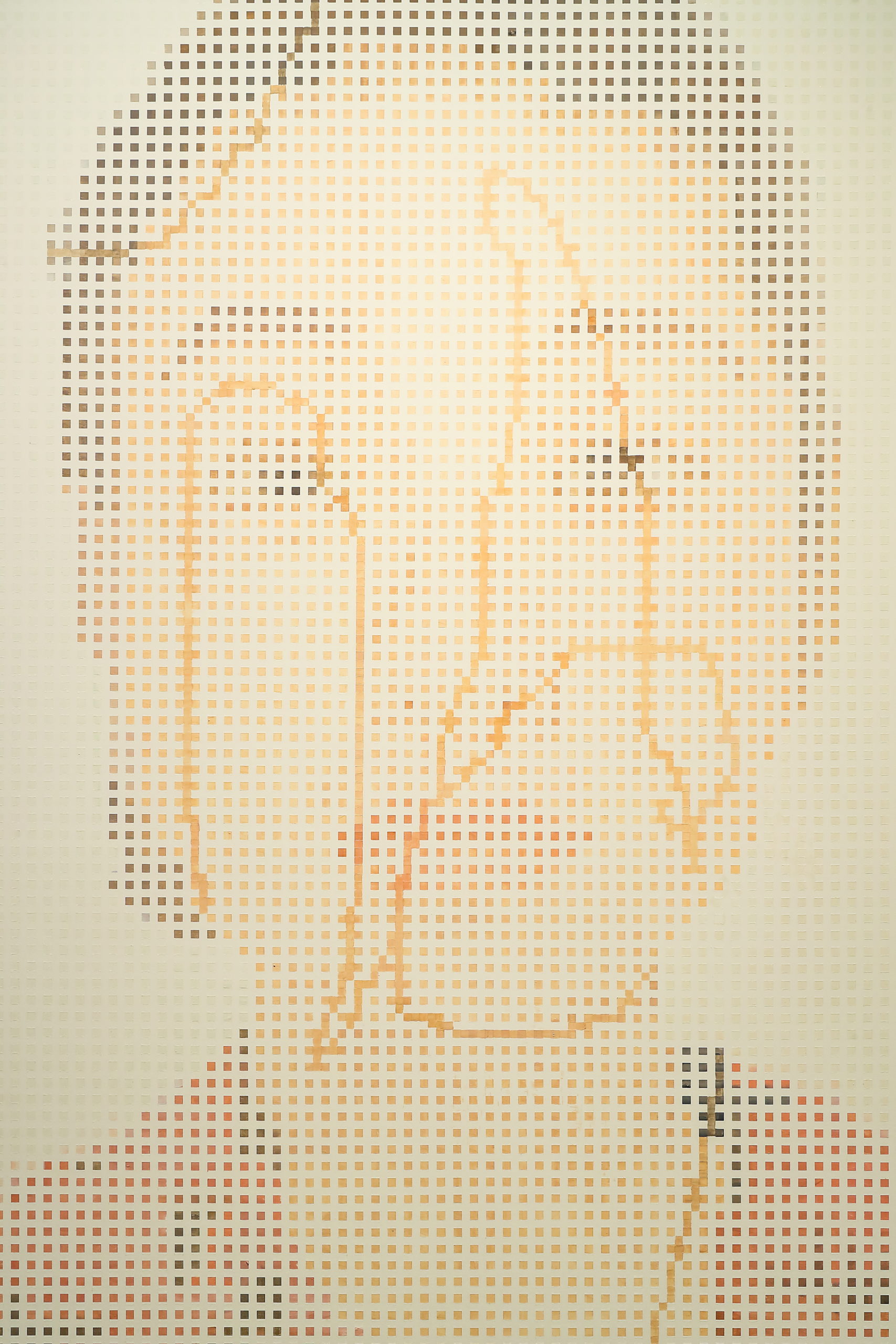

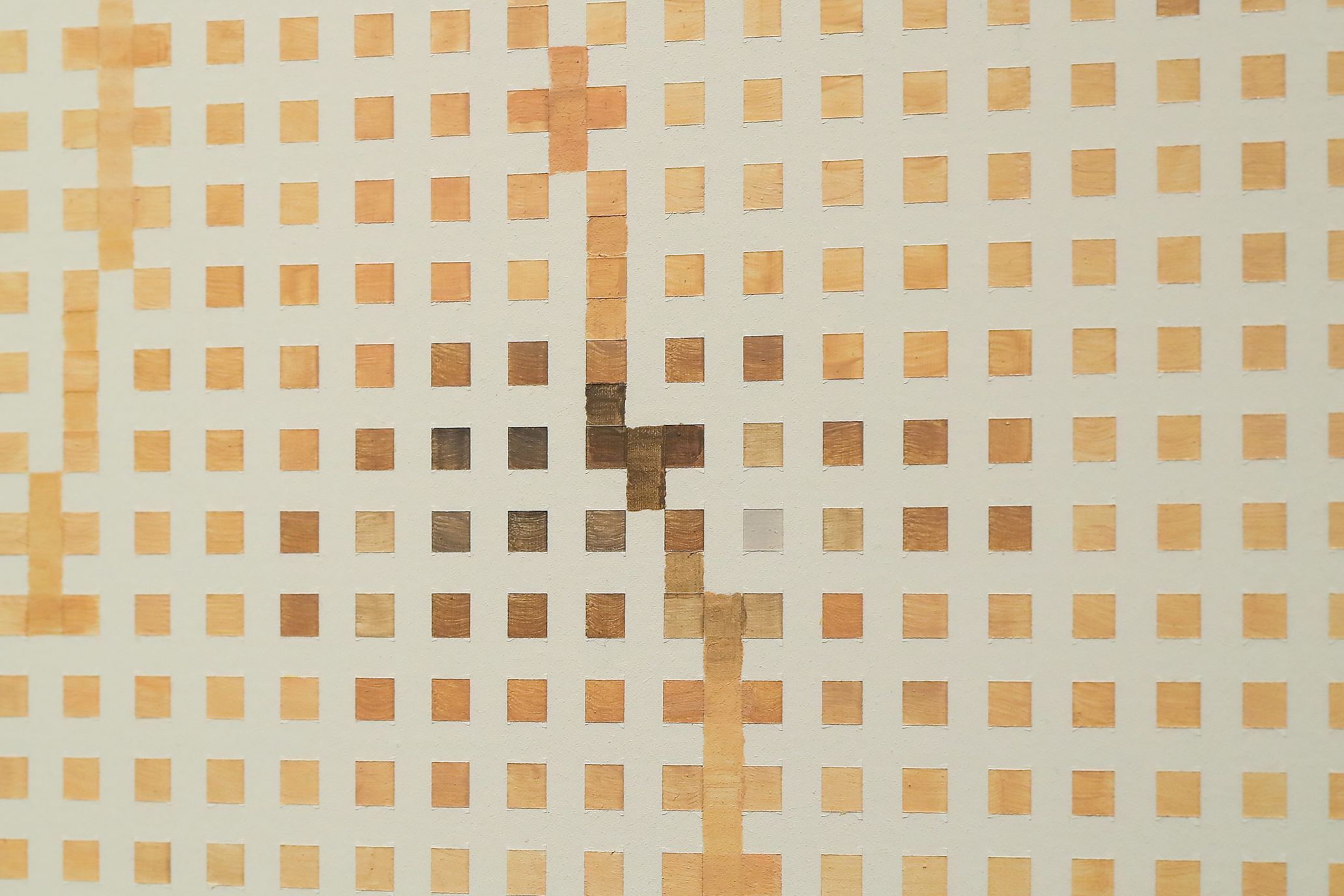

If you look at “tie” from a certain distance, the work functions as a portrait, but when viewed closer, the image is broken down into concrete objects like the canvas or paint. I feel it’s significant that the identity of this painting transforms as the viewer’s body moves. Also, pastel is a medium that can’t be fixed, and can be modified forever. Since the painting can be transformed by the viewers’ touch, the painting itself has a precarious existence.

――There have been many works in art history that use the human face as a motif, similar to your portrait piece “tie” (and “body to body”) . Why did you choose the human face for this series?

soh: The face is a very unique part of the human body. That’s why people have been painting portraits for so long throughout history.

――In “tie,” you used acquaintance’s ID photos. IDs are supposed to have visual information in high resolution because they need to be identifiable to others. Since you use pixels to express your portraits, the resolution of the visual information is lowered. Did you purposely create this discrepancy?

soh: I think the opposite is true. I believe that in terms of identifying an individual, a living and breathing body is in the highest resolution.

Therefore, logically, what an ID tries to do is use minimal icons and symbols to represent someone. I think it’s easy to understand this when we think about the example of the My Number system*. I think I critique this process by turning it into art.

*My Number system = A “social security and tax number” system that provides one unique sequence of numbers to all registered residents in Japan.

――Each work has a different pattern of pixels, right?

soh: The position of the person or the way they look should change depending on where the work is placed. By adding sharpness, you can get a sense of depth, and by using a border, the person appears to be in higher resolution and looks like they’re floating. It’s called a picture space, but I adjust that according to how I want the image to be formed in the painting. I’m often asked this, but I don’t change the pattern based on the subject’s personality.

――Your album art for “SLUMBERS2” by Hiroshi Fujiwara, who is also a guest lecturer at your alma mater, Kyoto Seika University, garnered a lot of attention.

soh: When he came to the university to give a lecture, my work happened to be displayed on campus. He saw that, and that was how we came to know each other.

――What were the emotions behind the work?

soh: Just as I have a relationship with each model in my portraits, I approached Fujiwara-san as an individual human being, and that’s how I created the work.

――You made “etude” and “caress and hug” by putting soil in a coffee grinder to make pigments, and then hardening those pigments to make your own pastels. Why did you decide to use those materials?

soh: First, let me just say that making my own pastels wasn’t the focus of this painting. Store-bought pastels come in sticks, which means the painting comes out looking like they were drawn with that shape. When pastels are molded into a ball, they’re easier to grip and more flexible in expression. The same is true for color. As I mentioned earlier, I use pastels because of their high malleability and the fact that they can be modified forever.

――Will the pigment remain intact as long as it isn’t impacted in some way?

soh: Yeah, as long as there’s no damage, it should remain in its original state. Compared to oil paints, they weather a bit quicker, but I think that uncertainty brings about a tension in the structure. Also, because they’re not fixed, the reflection of light is more varied, and the colors appear lighter than when you use paints.

――When I actually saw the work at the exhibition space, I felt like they possessed a kind of human warmth, even though they were paintings. Of course, this feeling is quite subjective.

soh: Thank you.

――In “my body, your smell, and ours,” you used 25 different herbs and fragrant trees that were collected with the intention of healing and cleansing.

soh: In this installation, I created a three-dimensional piece in the form of a body and placed herbs and fragrant wood inside it. The individual fragrances mix together to create a kind of odor, and I find meaning in creating a collection of fragrances. I tried to create a place where people could connect and affirm each other beyond the boundaries of the body. I also used herbs and such that have been used since ancient times, and presented them with the hope that this collection of herbs would heal and restore.

――I heard that you were ill yourself. Does that have anything to do with this?

soh: Yeah. I think that’s what led me to dream up the concept, or I guess it actually influenced the entire exhibition.

――On the other hand, you could have chosen to hide it rather than express it. Is there a reason why you decided to reflect it in your work instead?

soh: I always have a hard time deciding how much of my work should be personal. I think that showing your work at an exhibition is a way of communicating something socially relevant, but I also want it to be something that’s close to my personal experience. I always try to find a balance between the two.

This time, however, I couldn’t help but feel something happening inside my body, something that even I couldn’t understand. So, I was interested in what kind of social message would be born out of this first-hand experience.

――Did your solo exhibition “A Modest Scream” lead to any discoveries, like a new realization or a confirmation of where you are in your journey?

soh: I disappeared into one of the viewers at the gallery, and observed how the viewers were interacting with the work. With the portrait, “tie,” on the first floor, I felt like most of the viewers were looking at the work through their iPhones or other cameras. That was my biggest point of reflection with this exhibition, and I think it’ll lead to points of improvement in future works.

Also, in the second floor installation “my body, your smell, and ours,” I randomly scattered 25 cardamom seeds on the floor of the gallery and then arranged 25 sculptures in a scattered manner according to that. Since viewers entered the space as if they were wading through the scattered three-dimensional objects, I think many of them moved very slowly around the venue, viewing the exhibition with awareness of their bodies.

What can I say as an artist?

――That’s definitely the effect that the installations have. Although, as you mentioned, with the spread of digital tools and social media, it’s become more common to view artwork through a camera while at the venue. It’s also true that with the coronavirus, physical experiences and communication have waned. As an artist, what do you think of this

soh: I’ve benefited greatly from technology, too. However, I also have my doubts about whether it’s really a good idea to develop in such a way as to neglect or become separate from our bodies. Online communication is convenient, but is it enough just to relay information? I wonder if there’s something that we’re fundamentally looking for beyond that. Of course, I don’t mean to say that one is better than the other, but that it’s a matter of balance.

――The coronavirus pandemic hit us hard in 2020. Did the coronavirus change your perspective or your work situation/environment? Also, what were you up to during the coronavirus?

soh: I spent the past year doing nothing but working on my solo exhibition. It was a year in which many things happened—not just the coronavirus, but also political and social issues. But the days when I spent most of my time going back and forth between my studio and home were quiet in contrast to the chaos of society. I think that quietness saved me in many ways. As for the coronavirus pandemic that’s still going on, it seems that the only thing we can do in today’s technologically-advanced world is keep a distance of two meters from others and avoid contact.

That’s how powerful the territory of the body is, and this year has allowed me to actually understand how much each individual body can influence the world.

――Lastly, could you tell me about your current mentality and any visions you have for the future?

soh: I think a lot about what I can say as an artist. Maybe there’s nothing I can do. If that’s the case, I might choose something in a different field. In terms of my work and knowledge, I’m still inexperienced, and I’m in the process of developing myself. There are a lot of things I learned from this exhibition, and I also found challenges and things to reflect on. I would like to carefully grow through the process of answering these reflections and questions one by one.

soh souen

soh souen was born in 1995 in Fukuoka, Japan. Since graduating from university, he has consistently explored contemporary painting in relation to existing within a body by focusing on identities such as the body, the self, and the other. Since his early work “body to body,” he has expanded his expression of the self through works like “tie” and “caress and hug” in his current exhibition. The current exhibition at The Mass is his second exhibition since participating in the 2018 group show “PORTRAIT,” and his first-ever solo exhibition.

https://soh-souen.com/

■“A Modest Scream”

Dates: to December 27th

Venue: The Mass

Address: 5-11-1 Jingumae, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo

Time: 12:00 – 19:00

Closed: Tuesday, Wednesday

Admission: Free

URL: http://themass.jp/en/1/2020/

Photography Satoshi Ohmura

Text Takashi Suzuki

Translation Aya Apton