He writes his own songs, sings for them, and even dances in his own music videos: Hiroshi Fujiwara released his new album “slumbers 2” in October, in which he took part not only as a music producer but also as a singer-songwriter. The album comprises a compilation of songs that blends various genres, from city pop and vaporwave, which have been through a global revival in the recent years, to disco and folk. “Like the previous album, ‘slumbers,’ I’m not particularly trying to make new music that is popular right now,” he says. “Actually, regardless of whether it is ‘new’ or ‘old,’ I honestly just want to put out whatever is in my archive of things that I like and want to do.”

“Archive” and “things that I like” – What kind of music scenes and movements have become the blood and flesh of Hiroshi Fujiwara? From his “addiction” to punk rock in middle school, to his encounter with hip hop in New York and his career in house music as a DJ; while unraveling his new album “Slumber 2,” we explore the past and present of musician Hiroshi Fujiwara.

The “smooth and natural process” from punk rock to hip hop

–Punk and hip hop; I think that these two genres are important to you, but first of all, I would like to ask you the reason why you were obsessed with them.

Hiroshi: I got into punk around when I was in my second year of middle school. Children at that age like rebellious, bad boy-ish stuff, right? I think punk hit that spot just right. I sympathized with punk’s defiant spirit and style, which is different from bōsōzoku (Japanese motorcycle gangs). In 1982, I went to London because of that, but the next year I moved to New York. Malcolm McLaren, who I met in London, told me that New York’s hip hop was getting interesting and suggested that I go there. At the time, musically speaking, punk was over, and hip hop was starting to catch everyone’s interest. Malcolm too, but also “The Clash” were trying to make something with hip-hop, and shortly after, “Sex Pistols” Johnny Rotten also collaborated with Afrika Bambaataa. It was a time when the people who were doing punk were also trying to adopt hip hop in their music.

–Punk rock and hip hop were strong influences for you at the time; what do they mean for you now?

Hiroshi: Punk has a lot of spirituality. It’s the kind of attitude that makes you do something a little strange or make fun of something popular. Hip hop is based on sampling, which is like reconstructing from what you already have, and that’s fascinating. This had an impact not only on music but on fashion as well.

–In Japan, you were active as a DJ since around 1983, and then formed the hip hop group “Tiny Panx” with Kan Takagi, which led to the advent of Japanese hip hop. In 1994, you released your first solo album “Nothing Much Better To Do,” declaring that “this is the beginning.” What did you mean by that?

Hiroshi: I simply meant that I wanted to hit the reset button once and release my solo album; nothing more. Before then, there was no release under my real name. However, as always, I wanted to make something different from other people, something weird for that album. At the time, step-recorded house music and ground beat (Japanese name for British soul music) were mainstream. It was full of people making music with brilliant diva-type singers, so in “Nothing Much Better To Do,” I went for types of music and singers that were different from the mainstream, like Terry Hall of “The Specials.”

–Why did you start pursuing music that is different from hip hop? Hiroshi: One of the big reasons is because I started liking house (which originates from disco) and house-like music more than hip hop. It was around the time when Public Enemy became popular and hip hop, in general, was advocating for “Black Power” and getting to be more and more serious. I’m Japanese, and I’m not really good at expressing my nationality, so I guess that’s what distanced me from hip hop.

To be honest, I make music and am influenced by what I like at the moment

–In recent years, you have also started to sing for yourself, which makes you more of a singer-songwriter. Before that, I think your style used to be more about expressing different world views by featuring various artists. What was your turning point?

Hiroshi: I just found the right timing inside of myself to stop with featuring projects. After all, with featuring, 70% of what you make goes to the featured person, which is also a good thing, but I’ve come to think that if I want to put out what’s in my head, I should sing myself.

–Your previous album “slumbers,” has been released by “NF Records,” which is owned by Sakanaction’s Ichirō Yamaguchi. How did that happen?

Hiroshi: It all started when a friend introduced me to Yamaguchi-Kun, and we got along. After that, I got to be in charge of remixing Sakanaction’s “Rookie.” Then, at some point, while talking to Yamaguchi-Kun about my album, I asked him if we could release it under his label, and he said: “let’s definitely do that.” And that’s how it got released.

–There is an age gap between you and Yamaguchi-San, but do you think you have a similar sense of music?

Hiroshi: I get interested in a lot of things, but I feel like Yamaguchi-Kun’s whole way of life is completely “music-centric,” and that may be different from me. However, he is a very charming person; there is something that draws people to him.

–Shunsuke Watanabe was working as a sound producer for your previous work too. You know him since you formed the band “AOEQ” with Yōichi Kuramochi of Magokoro Brothers, right?

Hiroshi: He has been on tour with me as a keyboard player since the days of AOEQ. We started working together because I fell in love with his sound. It’s very easy to produce music with him; he’s great at translating whatever I ask for advice from him into sound.

–It seems like getting along and falling in love are very important things for you.

Hiroshi: I would say so.

–In this new album, I’ve noticed many demo-sounding parts, like guitars that sound like they were recorded at home. It sounds like you were really enjoying the production process; were you trying to experiment with something new?

Hiroshi: For the most, I’m doing everything the way I’ve always done so far, but it may be my first time to sing disco-like songs by myself.

–In your song “SPRINGLIKE,” you’re whistling the main melody. I thought that was fresh.

Hiroshi: That’s a sample of a whistling instrument, so I’m playing it with a keyboard. I’m partially taking inspiration from Frankie Knuckles’ “Whistle Song,” which everyone in our generation knows about.

–You made music videos for every original song in the album, except for the covers. I was surprised to see you dance in the music video for “TERRITORY.”

Hiroshi: It’s been a while since the last time I made music videos. Yamaguchi-Kun suggested me to make them, but I thought it was too hard and expensive (laughs). I tried dancing for that song because it’s disco-like. There used to be a TV show called “Soul Train” that aired in the United States from 1971 to 2006, which I was also watching on Youtube, and the way people dance in that show is not too technical, it just looks like they’re having a good time dancing. I wanted to express that kind of feeling, so I decided to dance in the video.

–While producing a track, are you consciously thinking about generational differences in music?

Hiroshi: Not that much. The important thing is if I like what I’m doing or not. To be honest, I make music and am influenced by whatever I like at the moment. It doesn’t matter if it’s from the past or the present, it’s good once it goes through my filter. That is true not only for music but for fashion too.

–In recent years, city pop has been through a revival, and I was wondering how you’re digesting it. As a listener, do you have any thoughts about this music phenomenon?

Hiroshi: Actually, I haven’t listened to city pop in great detail. I very much like the new wave of city pop that is being made around Thailand, Indonesia, and all over Asia in recent years, though.

–You don’t even listen to Eiichi Ohtaki’s stuff from back in the days?

Hiroshi: I haven’t listened to that at all. Before going to middle school and listening to punk rock voluntarily, I was forced to listen to Yuming or whatever my older sister would put on since we shared the same room. From middle school on, I was all about Western music, and I couldn’t listen to Japanese music at all. However, thinking back, I think I was partially influenced by the 70s folk music my sister used to listen to. Listening to that stuff again now, I realize there are many good songs. Makoto Kubota, for example, I like him a lot.

–I guess folk music is part of your roots as a singer and composer.

Hiroshi: I think so. I think Sakanaction’s music also has folk-like roots. When Yamaguchi-Kun shows me his new songs, sometimes the chord progression is very folk. They’re really great at arranging though, so they make it sound almost like house music. I feel like they do some really cool stuff that I can’t do myself. It’s kind of what I felt when I heard Towa Tei making music in Japanese for the first time.

–How is your process of writing lyrics? The lyrics for “PASTORAL ANARCHY” in the new album feel quite ideological.

Hiroshi: When writing lyrics, I write down interesting words and sentences regularly, and once a theme is decided, I put them all together like a puzzle or a collage. For “PASTORAL ANARCHY” though, I wanted to make it into a song since way back. In an area of southern Switzerland known as Ascona, there is a place called Monte Verità where thinkers and anarchists who were disgusted by the German industrial revolution moved in to form a commune around the year 1890. I have been there many times, so I wrote the lyrics about its sceneries and utopian ideals. I wasn’t very aware of it, but it kind of matches the mood of the world these days. I don’t have a precise idea of utopia, but I am interested in the state of mind of people with such ideas.

–Regarding your new album, Yamaguchi-San of Sakanaction said that he could feel your loneliness even more than the previous album. The word “loneliness” really left an impression on me; does it ring a bell for you?

Hiroshi: It doesn’t (laughs). However, this album was undoubtedly influenced by what Yamaguchi-Kun’s NF Records and Sakanaction are doing. If it wouldn’t be the case, I would have never made such cold, house music sounding tracks. When I listened to NF Records’s music and all the DJs who work around Yamaguchi-Kun, I thought it’d be nice to include such elements.

It’s a culture scene that doesn’t evolve, but I still love music

–What genres of music are you personally focusing on, recently?

Hiroshi: I listen to both old and current music at random so I can’t say which one is better, but I also listen to a lot of new indie songs. The Asian city pop music I was mentioning earlier is good, and I also really like Beadoobee’s voice.

–In an earlier interview, you said that “fashion and culture haven’t evolved much since 1990. I often hear about 90s revivals, but the 90s might just not be over in the first place.” Do you see this “non-evolving culture scene” as boring?

Hiroshi: I don’t think it’s boring. However, it’d be nice to see or hear something that I have never seen or heard before.

–Why did music stop evolving after the 90s?

Hiroshi: In terms of music, samplers had a great influence on the music from the late 80s to the 90s. However, I don’t think that there has been anything revolutionary that changed the scene after that. Even vaporwave and chill-out music are actually influenced by the music that was created in the 80s and 90s. The same goes for fashion; these cultures have entered their evolutionary period of maturity. For example, from now on, we could enter a new period of evolution for different fields such as medical care, and that may entwine with music, creating something interesting that has never existed before. Like, if you listen to this beat, you will live longer, or this melody will cure your cold, or something like that (laughs). Whether new or old, I love music and fashion.

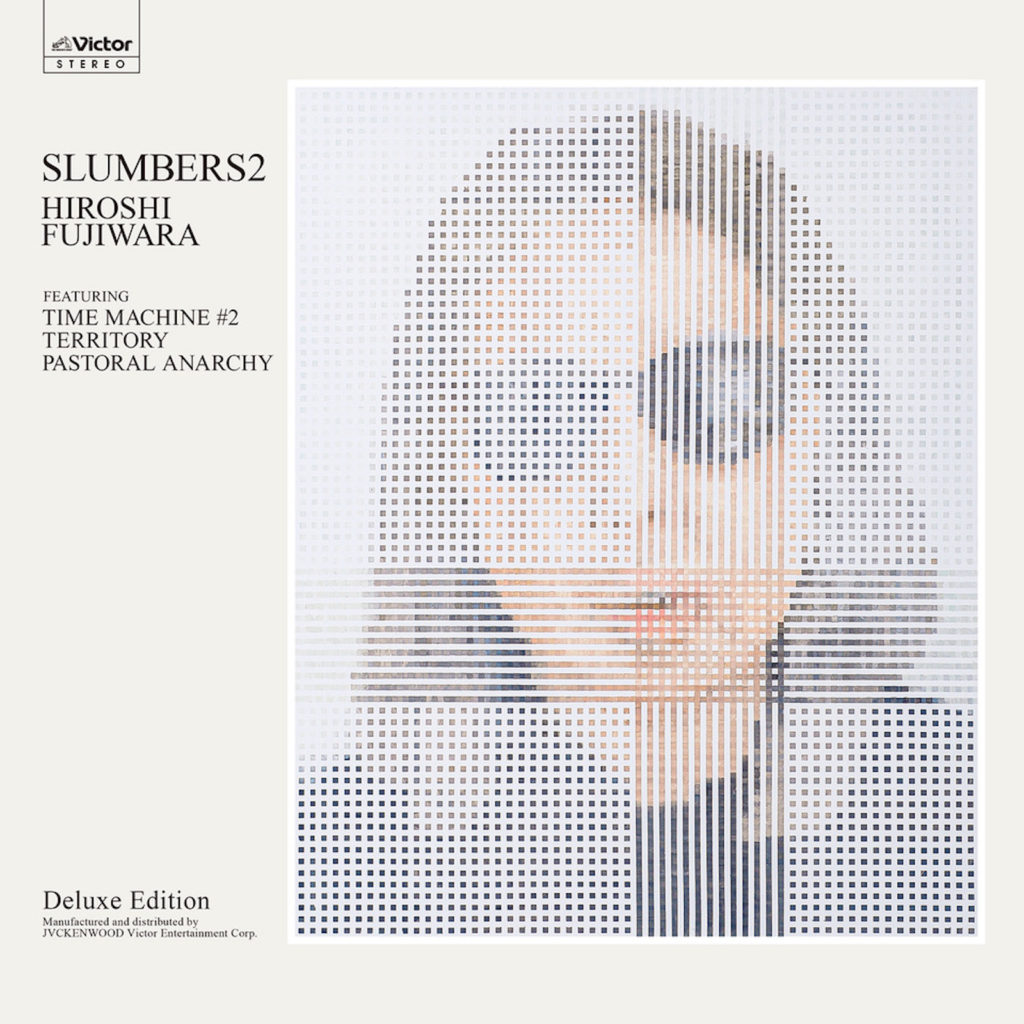

slumbers 2

This album is Hiroshi Fujiwara’s first original album in three years. In addition to a simple edition consisting of ten songs and bonus tracks, a deluxe and limited edition (only 2500 sets) was released at the same time. The deluxe edition, in addition to the standard edition’s CD, comprises different versions of all songs in the album, such as dub remixes, a special CD containing the music from the short movie “HARMONY” directed by Rinko Kawauchi, and a T-shirt. The streaming version also contains another version of “WALKING MEN” with lyrics written by YUKI.

www.jvcmusic.co.jp/fujiwarahiroshi/slumbers2/

Hiroshi Fujiwara

Musician, music producer, and founder of fragment design. He started being active as a club DJ in the 80s and formed “Tiny Panx” with Kan Takagi in 1985. From the 90s, he has expanded his activities to music production, composition and arrangement. Since 2011, he has also been performing in the band “AOEQ” formed with Magoro Brothers’ Yōichi Kuramochi. As a solo artist, he released the albums “manners” in October 2013, “slumbers” in November 2017 and “Slumber 2” on this year’s October 7.

Photography Kentaro Oshio

Translation Leandro Di Rosa